Integration of healthcare services has been advocated to improve quality and cost-effectiveness. Different models of integrated care for cardiology have been suggested, but the cost-effectiveness of a consultant-run service has been questioned. We assessed the potential impact on secondary-care outpatient volumes of introducing a service run by GPs with a special interest, with support from consultant cardiologists. We retrospectively reviewed all cardiology outpatient attendances at the South London Healthcare NHS Trust for a period of three months in 2011. Using National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines and discussions between cardiologists and GPs, a novel outpatient referral triage protocol was drawn-up to decide the appropriate minimum level of care required for a range of cardiac conditions. Anonymised clinic letters were divided into new referrals and follow-ups, and were assessed to establish the diagnosis and clinical complexity. Implementing such an integrated community care service (ICC) would reduce new referrals to secondary care by 33%, and would enable transfer of 44% of patients currently followed up in secondary care to ICC. The study confirms that there is scope for significant transfer of care with the greatest gains in patients with valve disease, ischaemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation.

Introduction

The increasing burden on healthcare services, combined with effects of austerity, has placed the National Health Service (NHS) under pressure to achieve ever-greater efficiency, while improving the quality of service. An example of the increased demand is that the total number of hospital outpatient appointments in England has increased steadily by more than 3% per annum since 2011.1,2

The increasing burden on healthcare services, combined with effects of austerity, has placed the National Health Service (NHS) under pressure to achieve ever-greater efficiency, while improving the quality of service. An example of the increased demand is that the total number of hospital outpatient appointments in England has increased steadily by more than 3% per annum since 2011.1,2

The government, in the 2010 white paper, set out a redesigned pathway endorsing clinically led services based on more effective dialogue and communication between general practice and secondary care.3 Thus, integration of healthcare services has been advocated to improve patients’ care and cost-effectiveness.4 Integration may be defined as organisation of services within and between care sectors with the aim of enhancing quality of care.5

Different models of integrated care for cardiology have been suggested. However, the cost-effectiveness of a consultant-delivered service in the community has been questioned.6,7 Our aim was to assess the potential impact on secondary care outpatient volumes of a service run by GPs with specialist interest (GPwSIs) with support from consultant cardiologists.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed clinic letters for all cardiology outpatient attendances, excluding rapid access chest pain clinics, for the two acute general hospitals of South London Healthcare NHS Trust (SLHT) for the period 1 August 2011 to 31 October 2011. Using National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, and the results of discussions between consultant cardiologists and GPs, a novel outpatient referral triage protocol was drawn-up to decide the appropriate minimum level of care required for a range of cardiac conditions.

Anonymised patient letters were divided into new referrals and follow-ups, and were assessed by one person (AK) to establish the diagnosis and clinical complexity. New referrals were classified into groups according to the referring complaint, while follow-ups were classified according to their main diagnosis. This protocol gave three possible tiers of care for each condition/patient, namely secondary care, integrated community care (ICC) or GP-led care. In addition, for each outpatient visit we recorded whether the patient was discharged back to their GP or followed up.

GP-led care was considered suitable for low-risk conditions, i.e. those not requiring specialist investigations, or stable patients already on appropriate treatment. ICC, by a GPwSI, was defined as a service that would cover patients presenting with cardiac conditions not requiring urgent assessment, but still entailing a cardiology follow-up or further cardiac investigation. Secondary-care review would be reserved for patients with high-risk or complex conditions.

Results

There were 2,163 patient visits reviewed. There were 1,092 new referrals and 1,071 follow-ups.

New referrals

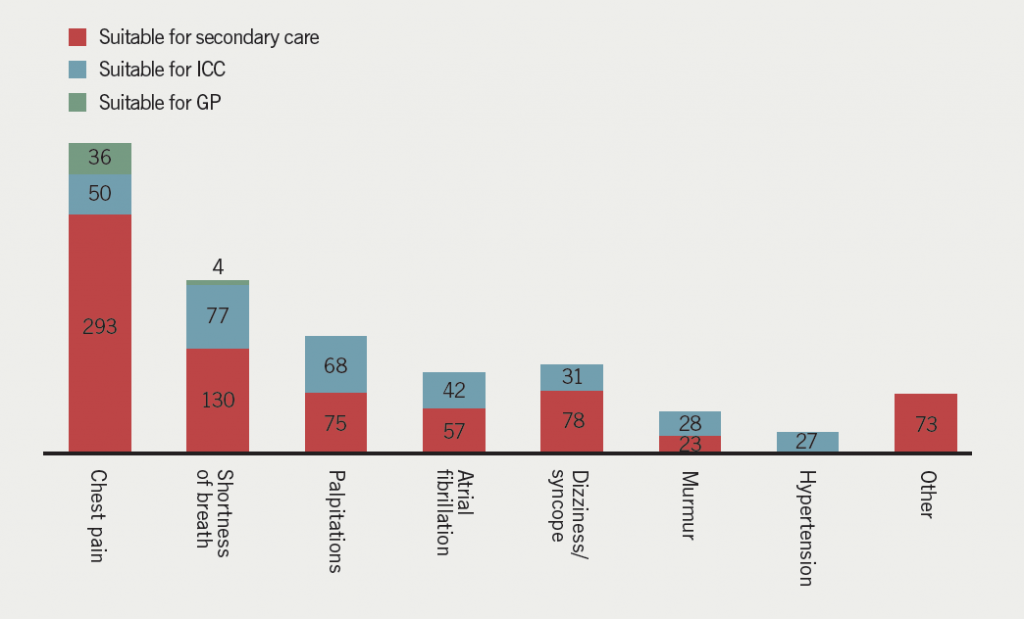

According to our referral triage protocol, 40 patients (4%) could have been treated by a GP, 323 patients (29%) by ICC and 729 patients (67%) would have required secondary care. Therefore, using an ICC model could reduce secondary-care referrals by 33%. The greatest percentage impact was in the murmur group (55% reduction), followed by the palpitations group (48% reduction), the atrial fibrillation (AF) group (42% reduction) and the shortness of breath (SOB) group (37% reduction) (figure 1).

The outcome of the new referrals consultations were: 679 patients (62%) discharged back to their GP without secondary-care follow-up and 413 patients (38%) offered further appointments. The projected clinical outcome with the new protocol, suggests that 77 patients who were offered follow-up (7% of the initial total) could be followed up in an ICC setting, leaving only 31% of total new referrals being followed up in secondary care after the initial assessment.

Follow-ups

There were 1,071 patients seen as follow-ups in the cardiology service during this time period. Of these, 383 patients (36%) were discharged back to primary care and 688 (64%) were followed up. Predicted figures, assuming implementation of an ICC, project that the number of patients being followed up in secondary care would fall from the observed 688 to 384 (44% reduction). The greatest impact would be observed in the valve disease group (54% reduction). Figure 2 shows the predicted impact of implementing ICC for each diagnosis group.

Discussion

Integration of healthcare services has been advocated to improve quality and cost-effectiveness. Integration may take different forms, but one model that has been suggested is for hospital consultants to carry out clinics in the community. Such an example of integrated care was reported by Knowsley PCT. Early reports of such service outcomes were positive, demonstrating a 10% reduction in unplanned hospital visits and a 12.6% decrease in short-stay admissions for cardiology-related events.8However, the value for money has been questioned,6 and our study examines the potential for improvements in efficiency by transferring services to primary care, supported by secondary care, rather than just putting consultants in a different setting. Our data demonstrate that 33% of new referrals to cardiology outpatient clinics, and 44% of patients currently seen as follow-ups in secondary care, could be seen in a GPwSI ICC service. The reduction in secondary care numbers is effected by providing the ICC and would not affect the usual primary care workload.

Targeted GPwSI clinics, with appropriate physiologist support, could provide a service for new patients with shortness of breath, murmurs and palpitations/AF, and for follow-up of valve disease, heart failure and AF, as well as chest pain and known coronary artery disease (CAD), taking significant numbers of patients out of secondary care. Clearly, good links would be required between primary and secondary care to enable patients to be fast-tracked to secondary or tertiary care once their clinical condition changed.

Integrated care is ultimately about achieving better care through better coordination,9 and current evidence suggests a potential to improve service quality and patient experience.10 However, there is a need for more solid evidence to decide how to develop this further, as longitudinal studies on the implementation of integrated care are scarce. Our study confirms that there is scope for significant transfer of care and indicates where the potential gains may be greatest.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Integrated cardiology care run by GPs with a special interest, with support from secondary care, would improve service quality

- The study showed that the greatest gains in transferring care were in patients with valve disease, ischaemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation

Integrated care should be based on patient benefit: a GP comment

Getting the right patient to the right doctor has always been a major challenge for the NHS. Referral triage is becoming more common and is based on commissioners saving money for their local health economies. Providing an intermediate service is a half-way house in that the patient is directed to an alternative service rather than no service. Analysis of the impact on services and potential savings is to be welcomed, and Khwanda et al. provide such an analysis in this issue. The paper shows that the impact was mainly in taking pressure off the consultant service, rather than saving money. This was achieved particularly in valve disease, ischaemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation. Making an evaluation of the economic savings is complex and potentially difficult. Tariffs are simplistic and do not necessarily account for secondary costs, such as clinic support staff and investigation resources. Quality and patient outcomes are the most important measures. Is the service safe? What is the patient satisfaction? Who is responsible if things go wrong?

Only 4% were thought to be suitable to be treated by their GP, and this surprised me. I felt it would be more and I wonder if there were opportunities here for feedback to educate the GPs? It may reflect the bias of a paper with five cardiology authors and no primary care input.

Dr Terry McCormack

General Practitioner

Whitby, North Yorkshire

References

1. Health & Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Outpatient Activity 2012–13. London: HSCIC, 2013. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB13005/hosp-outp-acti-2012-13-summ-repo-rep.pdf

2. Health & Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Outpatient Activity 2011–12. London: HSCIC, 2012. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB09379

3. Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London: HMSO, July 2010; pp. 27–9. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213823/dh_117794.pdf

4. Department of Health. High quality care for all. NHS next stage review final report. London: HMSO, 2008; pp. 65. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228836/7432.pdf

5. Curry N, Ham C. Clinical and service integration. The route to improved outcomes. London: The King’s Fund, 2010: pp. 2. Available from: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/clinical-and-service-integration

6. Ham C, De Silva D. Integrating care and transforming community services: what works? Where next? Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre, 2009. Available from: http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/publications/PolicyPapers/Policy-paper-5.pdf

7. Sibbald B, McDonald R, Roland M. Shifting care from hospitals to the community: a review of the evidence on quality and efficiency. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:110–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/135581907780279611

8. Ham C, Smith J, Eastmure E. Commissioning integrated care in a liberated NHS. London: The Nuffield Trust, 2011; pp. 55. Available from: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/commissioning-integrated-care-in-a-liberated-nhs-report-sep11.pdf

9. Shaw S, Rosen R, Rumbold B. What is integrated care? London: The Nuffield Trust, 2011. Available from: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/what_is_integrated_care_research_report_june11_0.pdf

10. Ramsey A, Fulop N. The evidence base for integrated care. London: NIHR King’s Patient Safety and Service Quality Research Centre, Kings College London, 2008. Available from: http://www.vision2020uk.org.uk/library.asp?libraryID=1293§ion=