Drs Thornton-Chan and colleagues write about how well patients with coronary artery disease are being managed in the real world

The objective of this study was to look at how well patients with coronary artery disease are managed, and whether community-based angina clinics might be an alternative, or even more beneficial, to these patients compared with hospital-based clinics. Patients with coronary artery disease need regular follow-ups to review their lifestyle and medications, and to ensure angina symptoms are well controlled. Heart rates should be checked regularly as high heart rate is associated with increased risk of myocardial ischaemia. In this study, 41 patients with coronary artery disease were assessed at a community-based angina clinic. Our results showed that 27% of these patients were significantly symptomatic and a significant proportion of these symptomatic patients were not on optimal prognostic secondary prevention medication. For those on optimal medication, many were not on optimal dosage. The data suggest that patients have not been monitored closely enough. We are suggesting that community-based angina clinics, such as the one in this study, may be an alternative to – or be supplementary to – hospital-based clinics.

Introduction

Patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease should be on prognostic secondary prevention medications. We looked at four such agents: antiplatelets, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and beta blockers or other rate-limiting agents. With the latter two agents, for best prognostic outcome, close monitoring is required to ensure suitable titration to the maximum tolerated doses.

Coronary artery disease patients benefit from a low heart rate achieved by up-titration of a beta blocker to the maximum tolerated dose. Several studies suggest that heart rate is a major determinant of myocardial ischaemia.1,2 According to a subgroup analysis of the BEAUTIFUL trial, a heart rate of over 70 beats per minute (bpm) increases the risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event in patients with coronary artery disease. There is good evidence that reduction in these patients’ heart rate, by optimising the dosage of beta blockers,3 will improve their prognosis.

The purpose of our study was to ascertain:

- whether or not patients with coronary artery disease are on optimal treatment for symptomatic control

- whether they are on optimal secondary prognostic prevention medications

- and whether a community-based angina clinic is a viable alternative to a hospital-based clinic.

Method

Patient selection

An angina clinic was held once a week in the evening at Clarendon Medical Centre in Cheshire between January and March 2011. All patients registered with this practice were included in the study provided they met all of the following criteria:

- they were previously diagnosed with coronary artery disease

- the patient had requested glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) for angina on two or more occasions in the past year

- they were capable of travelling to the clinic.

Some 86 patients fulfilled these requirements and were invited to partake in the study. A total of 41 patients from this cohort attended.

Data collection

Patients were either seen by a doctor PSI (Practitioner with Special Interest) or a nurse PSI. Data were collected on each patient’s symptoms, their heart rate, their current anti-anginal medications, and their current secondary prognostic prevention medications. Each patient was also asked to complete a satisfaction questionnaire consisting of two questions:

- how satisfied were they with the clinic?

- and would they attend such clinics again in future?

To further assess the use of secondary prognostic prevention medications (specifically beta blockers/other rate-limiting agents and angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs]), information was extracted from each patient’s file on the computer database at the practice. In patients who had never been on these medications, past medical notes were searched for a valid reason. In patients who had previously been prescribed these medications (but were no longer on them), the database was used to find out why these had been stopped. The beta blocker/ACE inhibitor dosages were also recorded to identify patients who were on suboptimal doses and the reasons for this. The database was also used to ascertain the reason for suboptimal dosage of these medications.

Results

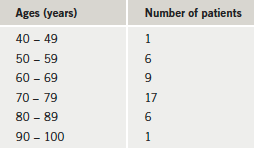

Some 41 patients attended the angina clinic out of the 86 patients initially invited to participate. High numbers declining were reported to be due to unpleasant weather and dark nights. The study cohort comprised 18 women and 23 men (age range 49–95 years) (table 1).

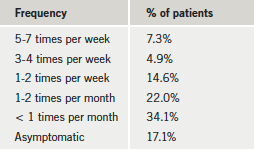

During the first visit, patients were asked whether they experienced angina. The frequency at which angina was experienced is shown in table 2. A significant 7.3% of our patients were experiencing angina at least five times a week, 12.2% had angina three to seven times a week, and 26.8% had angina on a weekly basis. Of the five patients with angina at least three times a week, two were being considered for referral to hospital, and one was already under hospital care.

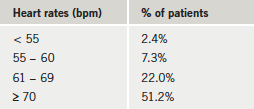

Looking at resting heart rate, this was found to be between 55–60 bpm in 7.3% of patients, less than 70 bpm in 31.7% of patients, and 70 bpm or over in 51.2% of patients (table 3).

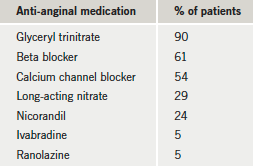

During our review of these patients’ anti-anginal drugs, we found the majority (90%) were on GTN, 61% were on beta blockers, 54% were on calcium channel blockers, 29% were on long-acting nitrate, 24% were on nicorandil, whilst a small number of patients (5% each) were on ivabradine and ranolazine (table 4).

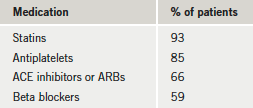

Table 5 illustrates the percentage of patients seen in the clinic who were taking the four prognostic secondary prevention medications. A good proportion of patients were on both statins and antiplatelet drugs (93% and 85%, respectively).

We looked in more detail at the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs and beta blockers/other rate-limiting agents. We found that of the patients who were not on ACE inhibitors/ARBs, only 14% had a valid reason for this. The remaining 86% did not have a valid reason.

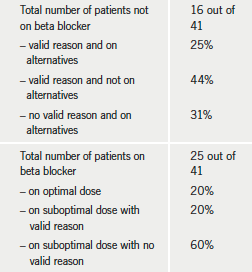

Table 6 looks at beta blocker use in more detail. Of those who were not on beta blockers, 25% had valid reasons and were on other rate-limiting agents; 44% had valid reasons but were not on other rate-limiting agents; and 31% did not have any valid reason but were on alternatives. For those on beta blockers, only 20% were on optimal dosage, 20% were on a suboptimal dose with a valid reason (such as optimal heart rate, low blood pressure and intolerance of higher dose), and 60% were on suboptimal dosage without a valid reason.

Discussion

There is good evidence that aggressive medical treatment is effective in managing symptoms and improving the prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease.4 We identified a significant proportion of our patients whose medications had not been optimised. Although 90% of patients attending the clinic were using GTN spray for symptomatic control, the use of other anti-anginal drugs seemed low. The low use of anti-anginal medications and the high proportion (26.8%) of significantly symptomatic patients (those experiencing angina at least once a week) are no coincidence.

The use of beta blockers (59%) and ACE inhibitors/ARBs (66%) was poor. The reasons given for either suboptimal treatment or no treatment with beta blockers, included asthma, bradycardia, intolerance, no prior use of beta blockers, and discontinuation due to unspecified reasons. For ACE inhibitors/ARBs, the reasons given were intolerance, no prior use of the drug, and discontinuation due to unclear reasons.

We noticed that discontinuation of medications sometimes occurred after a hospital admission or an outpatient clinic with no reason being given. Poor or delayed communication between the hospital and GP is a recognised problem. GPs may make changes to the medications prescribed to patients by hospital clinicians, if the reason for initiating the drug is unclear.5 The hospital discharge letters were generally clear in indicating which medications patients had been prescribed. Patients, however, may be uncertain which medications are to be continued, or may simply stop the medication when it has run out. Having community-based angina clinics could ensure continuity of care and also regularly review all the treatments patients receive. Hospitals, generally, do not have access to the patients’ GP notes. As every patient’s past medical notes from both hospitals and GP consultations are all readily accessible at the community clinics, it may be easier to identify why treatments have been started or stopped.

We are aware that some of our patients did not attend their hospital appointments, which may have resulted in their poor therapeutic management. Reasons for missed appointments may include the distance, patients being unfamiliar with hospital clinicians and/or not knowing the reason why they have been given the appointment. Patients are likely to be more familiar with their own GP, which may make it less intimidating to communicate during a consultation. It may also be easier and quicker for patients to access a community-based clinic, which would reduce the waiting time between subsequent appointments, thereby allowing symptomatic patients to be assessed more rapidly in comparison to a hospital-only angina clinic.

Possible issues with community-based clinics are that although GPs receive hospital letters regarding patients’ hospital stays, investigations or appointments, information regarding community-based consultations is not usually passed on to hospital clinicians. Another issue could be the PSI’s capability and experience of managing patients with coronary artery disease. If PSIs have the prescribed qualifications, this is not generally a problem, but it could lower patients’ confidence levels in community-based angina clinics.

In addition, community-based angina clinics are unlikely to have on-site echocardiogram or exercise tolerance test facilities although ECGs and 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure profiles are widely available.

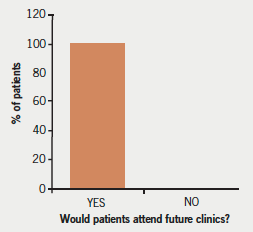

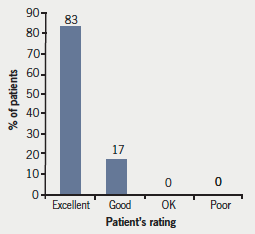

Lastly, however beneficial community-based clinics are for patients, it is crucial that they are satisfied with the clinic to ensure attendance. In this respect, our angina clinic was extremely successful with 100% of the cohort of patients reporting they would attend the clinic again (figure 1). The majority (83%) of patients rated our clinic as excellent, whilst 100% of patients rated our clinic as excellent or good (figure 2).

Future considerations

To improve future attendance, we may need to provide earlier appointments during daylight hours and/or run the clinics in the summer months when it is still light in the evening. It would be interesting to look at the percentage of missed appointments at hospital clinics and the reasons for non-attendance. It would also be useful to compare our data with that of other studies similar to ours. One such study was done in Rochdale in 2011.7 Some of their figures were comparable with ours, such as beta blocker use, which was 47% in their study (59% in ours) and ACE inhibitor use, which was 68% in their study (66% in ours).

Conclusion

Our angina clinic demonstrated that a significant number of patients were not symptomatically controlled, and a significant number of patients were not on optimal prognostic secondary prevention treatment. These results suggest poor follow-up and management. These findings are broadly in keeping with that of other studies.6 It is possible that community-based angina clinics may be more beneficial than the current model of hospital-based clinics due to them being easier to access, and the fact that it is generally less daunting to see a GP/community-based practitioner than a hospital clinician. Our patient satisfaction was also extremely high. Thus significant unmet need we saw in patients with coronary artery disease may be improved by a community-based angina clinic.

References

- Andrew T, Fenton T, Toyosaki N et al. Subsets of ambulatory myocardial ischaemia based on heart rate activity. Circadian distribution and response to anti-ischaemic medication. The Angina and Silent Ischemia Study Group (ASIS). Circulation 1993;88:92–100.

- Macleod RS, Punske B, Yilmaz B et al. The role of heart rate in myocardial ischemia from restricted coronary perfusion. J Electrocardiol 2001;34 (suppl). doi:10.1054/jelc.2001.28825

- Fox K, Ford I, Stef PG et al. Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:807–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61171-X

- Maron DJ, Boden WE, O’Rourke RA et al. Intensive multifactoral intervention for stable coronary artery disease: optimal medical therapy in the COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1348–58.

- Department of Health. Primary and Secondary Care. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/

PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/Browsable/DH_4892113 - Elder D, Pauriah M, Lang C et al. Is there a failure to optimise therapy in angina pectoris (FORGET) study? Q J M 2010;103:305–10. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq011

- Carty R, Khandewal S. Primary Care Angina Review Clinic Main Outcomes (unpublished data 2011).