Undertaking a period of research in cardiology is considered a vital part of training. This has many advantages including enhancing skills that better equip the clinician for patient care. However, in modern cardiology training, the feasibility and necessity of undertaking a period of formal research during training should be considered on an individual basis. The first of this four-part editorial series will explore the benefits of and obstacles to pursuing research in cardiology, with the aim of equipping the reader with an understanding of the options around research during cardiology training in the UK.

Introduction

For those in cardiology training, finding research is often a daunting and multi-faceted process. The objective of this four-part series is to explore research in cardiology and will aim to serve as a reference point from finding the research, to applying for funding, straight through to the finish line (table 1). Although these editorials are targeted mainly at cardiology registrars and have a UK focus, they may be of interest to any medical or allied-health professionals looking to undertake research in the field of cardiology. The first part of this series aims to explore the role of research as part of cardiology training in the context of current training challenges.

Table 1. An overview of this navigating the research landscape in cardiology series

| Editorial number | Editorial content |

|---|---|

| Part 1: research – career necessity or bonus? | Exploring the role of research in contemporary cardiology |

| Part 2: finding the right research | Approaching a research group, different options for research degrees (MD vs. PhD, clinical vs. basic science) |

| Part 3: the application process | Funding bodies, ethics processes/approvals |

| Part 4: beyond the finish line | What to do on the ‘other side’ of finishing research |

New changes to the curriculum and impact on research

At the heart of patient-centered medicine is research, which drives progress and ultimately enhances care.1 However, with the recent changes to the cardiology curriculum and training structure, the question arises as to whether pursuing a formal research degree is both necessary and feasible. The new curriculum, which has been approved by the General Medical Council (GMC) and implemented from August 2022, places a greater emphasis on general medicine, yet it remains unclear how this will be balanced with the practical, skills-based curriculum required for cardiology training. Although participating in the general medicine rota can be beneficial, the time constraints it presents pose a challenge. However, Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board’s (JRCPTB) curriculum outline document2 still highlights the importance of research, with many trainees considering a research component as a means of staying competitive in the cardiology job market.

Despite such suggestions that research is central to modern cardiology training, it is important to note that academic cardiology is no longer a distinct sub-specialty area as it was in the previous system. To pursue a career in academia, one must complete training in general internal medicine, full sub-specialty cardiology, and research, which is a more demanding route than before.

Research: career necessity or bonus

Despite the challenges posed by the new training structure, many still consider a period of research during medical training to be an essential step in career development. Such a period is viewed as a valuable CV-enhancing exercise, offering opportunities for career networking and skill development that may not be available in a standard cardiology training programme (table 2). Additionally, a research period offers the advantage of being able to remain in one location for several years, building rapport and relationships that are otherwise difficult to cultivate during frequent rotations. Furthermore, time undertaking research may be necessary for those seeking certain types of jobs, such as in tertiary or quaternary care centres. The experience gained during a research period can be invaluable, equipping trainees with the expertise and credentials needed to stand out in a competitive job market and to excel in academic or clinical settings.

Table 2. Pros and cons of research

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| CV enhancing: publications, presentations, teaching and leadership opportunities | Extends training time |

| Opportunity to network in your chosen field | No on-call supplement to salary in research |

| Learn transferable skills, e.g. literature searching, team work, project management skills, time management | De-skill in practical procedures unless part of your research time |

| Opportunity to learn research-specific skills, e.g. lab skills, coding, statistical analysis, patient recruitment, ethics writing | Potential toxic environment of some research groups/academia |

Is a research degree necessary for tertiary/quaternary jobs?

Whether a research degree is necessary to work as a cardiologist in a tertiary or quaternary hospital centre in the UK depends on individual hospital policies, requirements, and career aspirations. While research and academic medicine are significant aspects of medical practice, some hospitals may prioritise clinical experience and practical skills over research training. Ultimately, the decision to pursue a research degree should be based on individual goals, interests, and aptitudes.

Arguments for a research degree include enhancing clinical expertise, managing complex cases, and meeting hospital requirements for academic and research responsibilities. However, many experienced cardiologists work in tertiary or quaternary hospitals without research degrees and provide excellent patient care. A research degree may not necessarily be directly relevant to clinical practice or guarantee better patient care, and excessive emphasis on research training may detract from the importance of clinical training and practical skills.

Is research right for me?

Cardiology is a dynamic specialty that prides itself on a large evidence base. But, how does one decide whether this is the correct path? While the answer is unlikely to be the same for everyone, exploring a number of avenues and considering the following areas, provides a structured approach.

When is the right time?

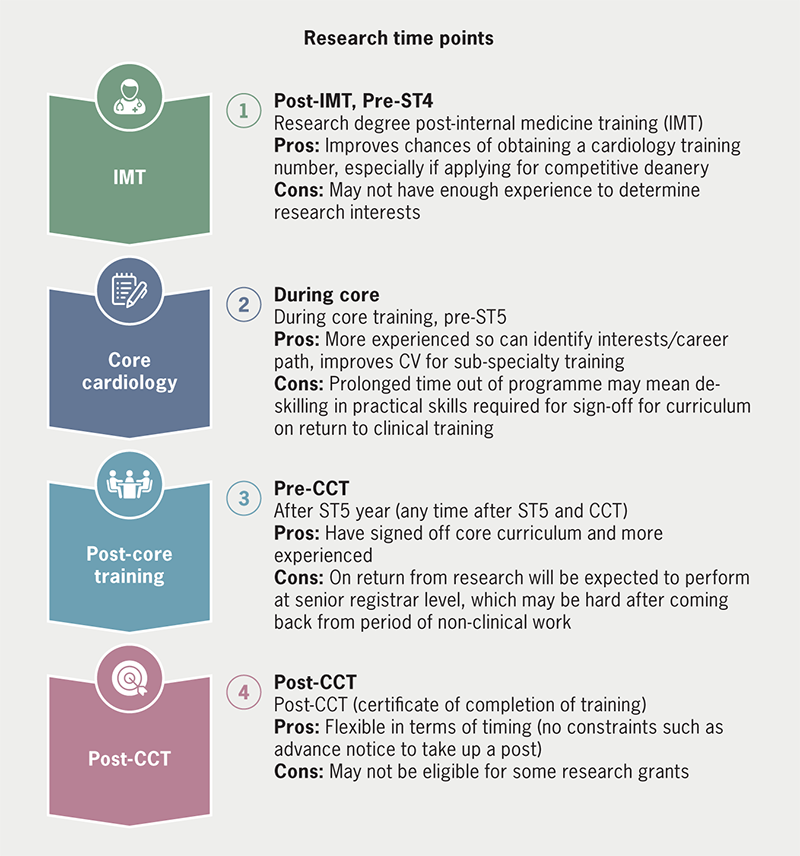

Training programmes are critical in shaping the careers of medical professionals and promoting consistent clinical services across institutions. In the UK, the JRCPTB2,3 sets guidelines and standards for cardiology training programmes in collaboration with other organisations, such as the GMC. Each deanery may have their own requirements for out-of-programme requests, which will be covered in a subsequent part of this editorial series. Figure 1 outlines common research time points, and the new curriculum does not strictly define core training years.

Your motivation behind undertaking research

Research fellowships offer a unique lifestyle that differs from that of a typical medical professional, as they usually involve working in an office or laboratory setting, rather than on a clinical ward. One of the benefits of this type of position is that it often does not require participation in an on-call rota. This can be particularly appealing for medical professionals who are looking to prioritise family time or raise young children. By not being on-call, individuals may have more flexibility to arrange their work schedules and to plan their personal lives, without the unpredictability and potential interruptions of being called into work at odd hours. This can also help to reduce the overall stress and demands of the job, allowing individuals to focus more on their research, and to achieve a better work–life balance. While there are certainly trade-offs involved in pursuing a research fellowship, the opportunity to prioritise family and personal time is often a significant benefit that should be carefully considered when making career decisions.

Despite the perception that research offers a slower pace of work, this can be challenging at times. Unlike the immediate feedback and sense of accomplishment that comes from working directly with patients in a clinical setting, research often requires a long-term investment of time and effort before any tangible results can be seen. This can lead to a sense of frustration and a lack of purpose, particularly for those who enjoy the day-to-day interactions with patients. It is important, therefore, to be clear about one’s motivations for pursuing research and to have a clear understanding of the long-term goals and benefits of the work. This can help to maintain motivation and a sense of purpose, even in the face of the day-to-day challenges and minutiae of research work. Ultimately, the rewards of research may be less immediate, but they can be significant and long-lasting, both in terms of personal and professional fulfilment, and in the contributions that research can make to improving patient care and advancing medical knowledge. Some of the advantages and disadvantages of research are listed in table 2.

What can’t you compromise on?

The quest to finding research in cardiology is helped if you know what you are willing to negotiate on. Narrowing things, such as location, is helpful to provide attainable research goals. It is helpful to also understand your long-term career aspirations and how much time out of programme you want to take (two year MD vs. three year PhD). Although the topic of your research is not always vital; having a focus may help to improve career trajectory. For example, if you are an aspiring imaging consultant then you may want to tailor your research towards a particular imaging modality.

If academia is the long-term goal, then obtaining a grant becomes more important. Grants from professional research bodies, such as British Heart Foundation (BHF) and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), are impressive when applying for academia roles. Applying for funding will be described in more detail in Part 2 of the editorial series. However, for most consultant cardiology jobs in the UK this is not a strict pre-requisite.

What are the alternatives to a formal research degree?

Alternatives to a formal research degree during cardiology training include fellowships, which offer specialised training in a particular area of cardiology, and can be clinical or research-based, and can be taken during or after cardiology training. Taught degrees, such as master’s degrees in leadership and management, can also provide valuable opportunities to gain a deeper understanding of healthcare systems and how to affect change in the NHS, although cost can be a barrier. Diplomas and postgraduate certificates can offer flexibility and remote-learning options. Overall, finding opportunities that align with interests and career aspirations, and seeking guidance and support from mentors and colleagues, can help to build a well-rounded set of skills and experiences during cardiology training without the need for a formal research degree.

Conclusion

While research may not be necessary for every cardiology trainee, it can provide valuable opportunities for personal and professional growth. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to research, and individuals should be prepared to seize opportunities and adjust plans as needed. Securing research is the first step, what follows then is a minefield of research terms and jargon. Cath lab and crash calls are swapped for costing research equipment, service level agreements and substantial amendments. Twitter can be helpful, so can other websites including the Good Clinical Practice, NIHR and Health Research Authority (HRA) websites. There are also excellent resources such as the “The ABCs of developing a clinical study” talk by Dr Rasha Al Lamee on the British Junior Cardiologists’ Association website.5 Research is not the right choice for everyone. And, in this new era of cardiology, is not necessarily a pre-requisite for securing a consultant job. However, with the right support, determination, and resources, those wishing to pursue research should not be discouraged by the challenges that may arise, as they are not insurmountable.

Key messages

- Cardiology trainees have various options to enhance their training experience beyond academia and research, such as fellowships, postgraduate certificates/diplomas, and taught degrees

- The new cardiology curriculum’s emphasis on general internal medicine presents a challenge to trainees pursuing a formal research degree, as it may require an extended period of training to attain the same level of clinical expertise as their predecessors. Additionally, academic routes are now more demanding as academic cardiology is no longer a distinct sub-specialty area

- While PhDs and MDs are unlikely to be strict requirements for tertiary/quaternary centre jobs, those with a passion for research and academia should not be deterred from pursuing formal research degrees

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

1. Kasivisvanathan V, Tantrige PM, Webster J, Emberton M. Contributing to medical research as a trainee: the problems and opportunities. BMJ 2015;350:h515. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h515

2. Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board. Curriculum for cardiology training. London: JRCPTB, 2022. Available from: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/specialties/cardiology

3. Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board. Annual review of competence progression (ARCP) decision aids. Available from: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/training-certification/arcp-decision-aids

4. Weissberg P. Training in academic cardiology: prospects for a better future. Heart 2002;87:198–200. https://doi.org/10.1136/heart.87.3.198

5. Al Lamee R. The ABCs of developing a clinical study. Available from: https://bjca.tv/video/research-career-development/page/2