Recent data from the 2009/10 national diet and nutritional survey show that the national dietary pattern has improved.1 Intake of saturated fats, trans fats and added sugar is lower than it was 10 years ago.1 Nonetheless, saturated fat intake remains greater than the 11% recommended level, at 12.8%; fruit and vegetable intake is estimated to be 4.4 portions/day; fibre 14 g/d and oily fish <1 portion per week. So improvements are still required in order to meet recommended targets.1

Post-MI patients are often very keen to make dietary changes. Many make drastic changes to their dietary pattern stimulated by their frightening experiences. EUROASPIRE III, a survey of risk factor management in coronary patients, showed that 92% of patients reported that they had made some sort of dietary change since their event: 73.5% changed the fat type they used, 77.9% increased fruit and vegetable intake and 64.9% increased fish intake. Unfortunately, these data are subjective and the patients’ intake was not quantified. Neither do the data identify the type or length of intervention these patients received in order to achieve these reported changes or for how long they were maintained.2

Changing lifestyle through diet

As many cardiac rehabilitation (CR) staff see patients frequently, they have unique opportunities to help patients change their lifestyles, including their diet. This frequent patient contact can provide continued support and maintain changes, helping patients to address difficulties if and when they occur. A previous survey of CR programmes in England indicated that there is a lack of dietetic support for many cardiac patients attending CR programmes.3 All too often, dietitians provide just a one-hour talk to the group during the education part of the programme. Consequently, it is essential that all rehabilitation staff have a clear understanding of the most important dietary messages.

Patients face many challenges when changing their diet. One of these is that they are bombarded with information about what foods they should or should not consume. Information about healthy eating is available in many formats and from many different sources, and identifying a suitable source of information can be difficult. It is essential that any team working with post-MI patients should ensure that the information they are providing is clear, consistent and based on data proven to reduce the risk of further illness (so-called secondary prevention).

Changes in dietary habits during CR, following individual and group sessions with a dietitian, were shown to be possible and maintainable after one year in both the EUROACTION study4 and a study completed by Leslie et al.5 Both these studies reported success in enabling patients to lower their fat intake, whilst increasing fruit, vegetable and fish intake. In addition, there was a significant increase in the number meeting the oily fish target in EUROACTION (although still only in 17% of patients),4 but this change in oily fish intake was not duplicated in the Leslie study. The barriers identified for the lack of oily fish intake in the latter included: smell, bones, cost and taste.

Setting realistic goals

To help patients make appropriate dietary changes and to reduce their risk, staff must work with the patients to identify realistic and achievable goals. All dietary advice and goals should be individualised and defined using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Timely) criteria. Advice provided to patients should be practical and in a format that they will be able to understand. This includes, for example, discussion of foods rather than nutrients. Providing support, motivation and help for the patients to develop strategies and goals to achieve their aims is essential. As with any behaviour change intervention, it is necessary that the patients be taught skills and awareness of barriers and problems such as relapse. Having the skills to cope with relapse will enable the patients to achieve longer-term objectives.

What advice should be given to patients?

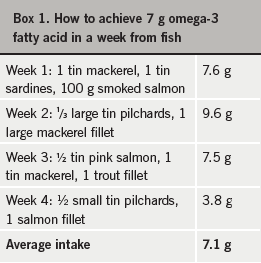

Focus should be given to the advice that has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality: namely, a change in fat use from saturated to unsaturated, increased intake to 7 g of omega-3 fatty acids a week (from fish or supplement, see box 1) and a Mediterranean-style diet.6,7 This diet is varied, with a high level of fresh fruit and vegetables, regular fish and oily fish consumption, lean meats, plenty of pasta, rice, wholegrains, nuts and seeds and the use of unsaturated fats, such as olive and rapeseed oil rather than butter and cheese. Once these objectives are achieved, then additional recommendations can be made to improve patients’ diet further.

Summary

- The national dietary pattern is improving but there remains room for further improvement.

- Like all lifestyle changes, dietary changes can be difficult for patients, especially in the longer term.

- Dietary advice should focus on the changes that can reduce mortality and morbidity (type of fat, omega-3 fatty acids, Mediterranean dietary pattern).

- CR staff are ideally suited to help patients make SMART goals and to monitor their progress to help prevent and deal with relapse.

Interview with Sue Baic

Q: Who is the best person to advise the post-MI patient about fish consumption?

A: Lifestyle factors play a vital role in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, so advice on any aspect can be a valuable way for a healthcare professional to reduce health risk in their patients.

Any healthcare professional can advise on fish consumption but what matters most is that the message is consistent and practical. Patients tend to disengage from the change process if they receive mixed or confusing dietary advice from different sources, and an opportunity is missed.

We have the evidence base to support a clear message to aim for at least two servings of oily fish a week (a portion size is around 140–150 g). Types of oily fish to recommend include salmon, mackerel, sardines, pilchards, trout and herring; these can be fresh, frozen, smoked or canned. We can also help by suggesting ways to use these fish economically and sustainably.

Q: With so many types of fish oil supplement, how do you recommend a good one?

A: As a dietitian, I always recommend aiming for food first. However for patients who have had an MI within three months and cannot, for whatever reason, achieve adequate dietary fish intake, NICE guidelines advise considering at least 1 g a day of a licensed omega-3-acid ethyl ester in supplement form.

Fish liver oils, such as cod liver oil, are not particularly good sources of omega-3 and tend to be high in vitamin A (retinol). Vitamin A can be toxic, especially to the bones and the liver, if taken in high doses over a long period.

Fish body oils are lower in vitamin A but some brands remain high in marine pollutants. Many, even those advertised as ‘high strength’, contain low levels of n-3 PUFA per capsule, meaning multiple capsules need to be taken daily to achieve adequate intakes. To improve compliance, a concentrated source containing 1,000 mg n-3 PUFA in a once-daily tablet may be most practical. To reduce gastrointestinal side effects, supplements can be taken as capsules rather than in liquid form and on an empty stomach just before a meal.

References

1. Bates B, Lennox A, Swan G. National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Headline results from Year 1 of the Rolling Programme. Food Standards Agency and Department of Health; 2010.

2. Kotseva K, Wood D, De BG, De BD, Pyorala K, Keil U. EUROASPIRE III: a survey on the lifestyle, risk factors and use of cardioprotective drug therapies in coronary patients from 22 European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2009;16(2):121–37.

3. Brodie D, Bethell H, Breen S. Cardiac rehabilitation in England: a detailed national survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2006;13(1):122–8.

4. Wood DA, Kotseva K, Connolly S et al. Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371(9629):1999–2012.

5. Leslie WS, Hankey CR, Matthews D, Currall JE, Lean ME. A transferable programme of nutritional counselling for rehabilitation following myocardial infarction: a randomised controlled study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58(5):778–86.

6. Mead A, Atkinson G, Albin D et al. Dietetic guidelines on food and nutrition in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease – evidence from systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (second update, January 2006). J Hum Nutr Diet 2006;19(6):401–19.

7. British Cardiac Society, British Hypertension Society, Diabetes UK, HEART UK, Primary Care Cardiovascular Society, The Stroke Association. JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart 2005;91 (suppl 5):v1–v52.