Dr Lindsey Tilling reports from the recent British Society of Heart Failure day for training and revalidation, held in Glasgow

The right ventricle

‘A walk around the heart’ was the title of the recent British Society of Heart Failure (BSH) day for training and revalidation. After passing through the left atrium and ventricle on our walk, we stopped at the right ventricle (RV). Our tour guide at this juncture was Professor Andrew Clark (Chair of Academic Cardiology, Hull York Medical School, and BSH President).

‘A walk around the heart’ was the title of the recent British Society of Heart Failure (BSH) day for training and revalidation. After passing through the left atrium and ventricle on our walk, we stopped at the right ventricle (RV). Our tour guide at this juncture was Professor Andrew Clark (Chair of Academic Cardiology, Hull York Medical School, and BSH President).

The causes of RV dysfunction were outlined initially. These can broadly be divided into left heart disease (ischaemia, cardiomyopathy, valve disease), RV failure (as for left heart), pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary artery hypertension [PAH], thromboembolic disease), and congenital (shunts, anomalous coronary arteries etc). The most prominent sign of right heart failure is peripheral oedema, and it is important to exclude other causes of fluid accumulation before attributing it all to heart failure. Investigation of right heart failure should therefore include serum albumin and protein levels, as well as lung function tests, arterial blood gases, chest x-ray, and urinalysis.

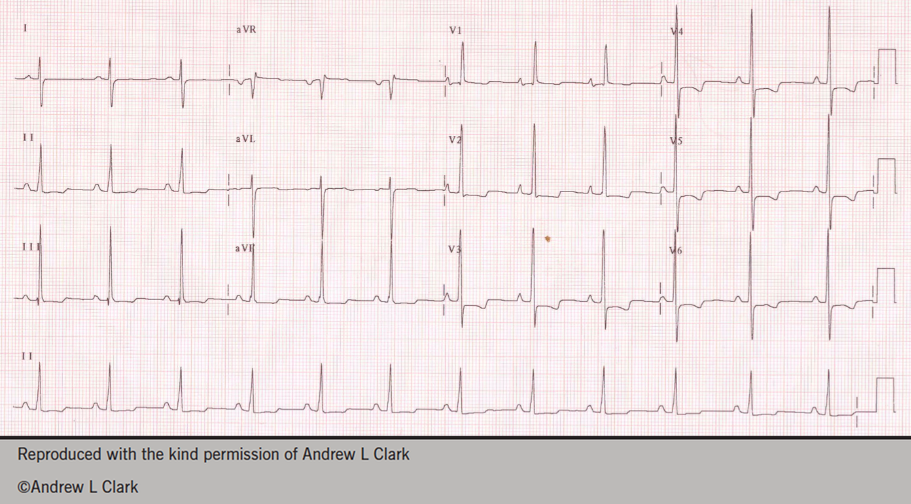

Several cases were then presented to illustrate the various causes of right heart dysfunction. The first was of a young woman referred with symptoms of right heart failure, but given a diagnosis of asthma. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) is shown in figure 1. The ECG shows RV hypertrophy, and the diagnosis was subsequently shown to be pulmonary arterial hypertension.

A case of RV infarct was then discussed, and radionuclide ventriculography was noted to be a useful technique for imaging the RV in this instance.

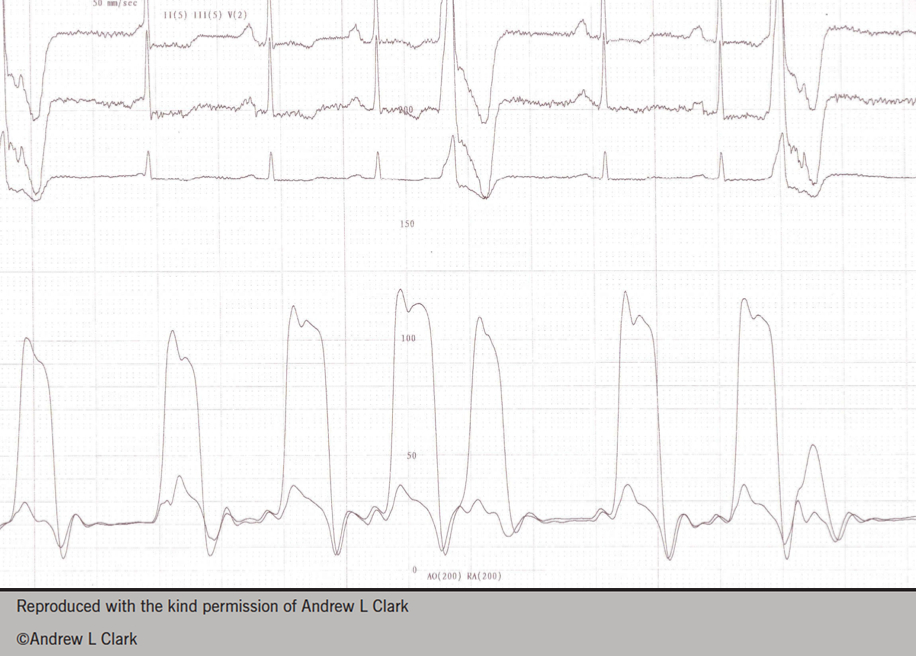

Symptoms suggestive of RV failure may in fact be attributable to something outside the heart. The case of a middle-aged woman was presented, who was known to have a 14-year history of rheumatoid arthritis and symptoms suggestive of heart failure. Her right and left coronary catheterisation data was presented (figure 2) illustrating equalisation of pressure within the chambers and the characteristic ‘dip and plateau’ of pericardial constriction.

Left heart catheterisation may be useful in the investigation of other, rare causes of RV dysfunction. Examples were shown of a coronary artery fistula and a ruptured sinus of valsalva found during investigation of right heart failure.

Valve disease is a significant cause of RV dysfunction. It is not uncommon to find a degree of pulmonary hypertension and RV dysfunction in association with prosthetic left-sided heart valves after they have been in situ for some years, and it is unclear how best to manage this.

Finally intrinsic RV disease can result in dysfunction: arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and Ebstein’s anomaly are two rare but important causes of RV dysfunction.

Management of RV dysfunction is targeted at the underlying cause, and as such the importance of thorough examination, investigation and diagnosis is paramount, in order to be diagnose aetiology and treat it effectively.

Pulmonary hypertension

Moving on to the next part of our journey, our guide was Dr Andrew Peacock (Consultant Physician/Director, Scottish Pulmonary Vascular Unit, Golden Jubilee Hospital, Clydebank). His focus was pulmonary hypertension and he identified four key messages:

- PAH patients die because the RV fails

- RV failure must be detected early

- It is important to discriminate between PAH and pulmonary hypertension (usually synonymous with pulmonary venous hypertension), which is a consequence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- To be effective, PAH treatment needs to show benefit on the RV.

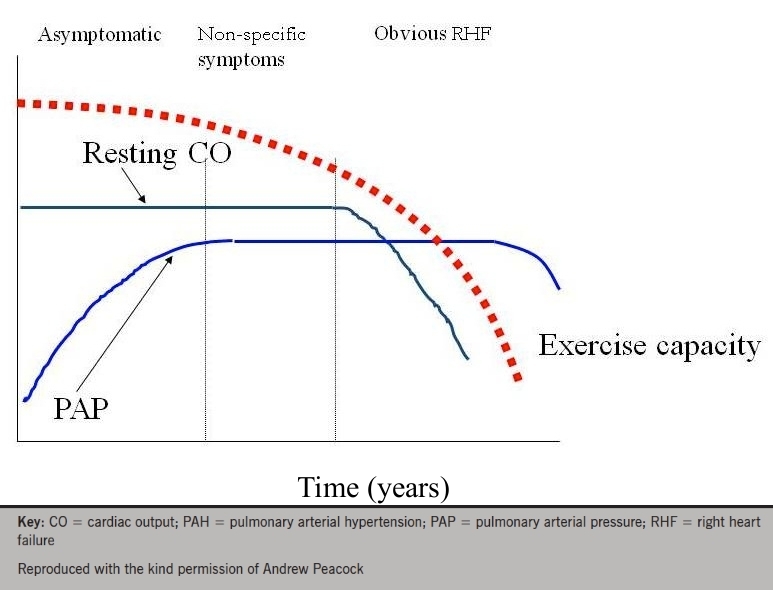

PAH can be idiopathic, heritable or acquired. Acquired PAH may be due to various drugs, connective tissue disease and HIV, among others. The time course of PAH progression was clearly illustrated: pulmonary artery pressure rises quite sharply, before reaching a plateau. At this point symptoms may start to occur, with an initial gradual decline in exercise capacity, becoming more pronounced in the later stages of the disease, when cardiac output finally begins to fall. There can be a time lag of several years between the onset of elevated pulmonary pressures and significant signs and symptoms (figure 3).

Diagnosis of PAH is not always straightforward. Chest x-ray and ECG should form part of the investigations, but may be unremarkable. Echocardiography can provide useful information regarding pulmonary pressures. A tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity of greater than 2.8m/s is suggestive of pulmonary hypertension, however it is essential to add right atrial pressure in order to derive the true pulmonary arterial pressure. The tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) length should be measured, as it gives a good indication of RV longitudinal function, and a value of less than 18 mm has been found to correlate with increased mortality.

The advantages of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) in this condition were also discussed. Imaging of the atria can differentiate between heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction, where the atria will be large, and idiopathic PAH, where the atria will be small (<40 ml), due to reduced filling. Additionally late gadolinium enhancement in the RV in patients with PAH has been shown to correlate well with functional variables.

Finally there was a brief discussion on treatment of PAH. Therapies such as the endothelin antagonist bosentan have been shown to lead to improvement in right and left ventricular function. This is as a result of improved stroke volume, rather than augmented ejection fraction.

Acknowledgement

The BSH gratefully acknowledges the support provided by HeartWare, Medtronic, Novartis, Pfizer, and Servier Laboratories.

Diary dates

European Heart Failure Awareness Day, 9th May 2014

BSH 17th Annual Autumn Meeting, 27–28 November 2014

Dr Lindsey Tilling

Whittington Hospital, Magdala Avenue, London N19 5NF

(ltilling@nhs.net)