Introduction

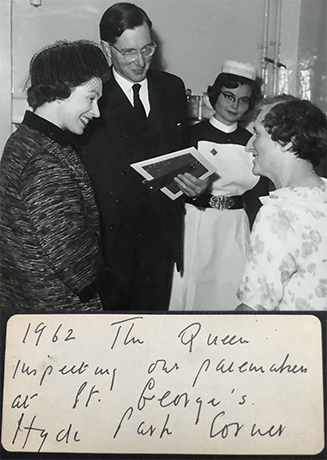

Permanent cardiac pacing began in Sweden in 1958 with Rune Elmqvist designing a device, and the cardiac surgeon, Åke Senning, implanting it. The US and UK followed quickly. The first UK implant was at St. George’s Hospital, Hyde Park Corner, London, in 1960 with Aubrey Leatham, cardiologist, and Harold Siddons, cardiac surgeon. Not to be omitted from this pioneering group was Geoff Davies, engineer. The implant was a success, and I had the privilege of looking after that patient in 1967 when I joined the St. George’s team. As raconteur of these stories, it is clear that I was a late arrival.

One of my first tasks as Pacing Research Fellow was to document the first group of patients, 53, all with complete heart block and Stokes-Adams attacks, who were paced at St. George’s. I presented their five-year data at the European Congress of Cardiology in Athens in 1968.1 The most striking aspect of their histories was the length of time that they had to spend as inpatients (>200 days) having their pacing problems solved, including lead fracture, stimulation threshold rise, infection and generator failure. However, their five-year survival was good >50% compared with the only data of the past that we knew. The latter was a study of a small group of complete atrioventricular block (AVB) patients who showed a 50% one-year survival.2 This convinced us that we were doing the right thing, despite the traumas endured by the patients.

Working for Aubrey Leatham was inspiring. He exhibited a youthful, physically fit image and clearly worked very hard. In contrast, Harold Siddons was dour, but a walking library of the world literature on pacing. As a surgeon, he was nicknamed ‘Septic Sid’ as his cases often seemed to be infected. On reflection, this was by no means all his fault as pacemaker implants generally took place at St. George’s, Tooting, South West London, the current site of St. George’s, and far from the main hospital at Hyde Park Corner (now the Lanesborough Hotel). The lead-insertion laboratory was borrowed from radiology for one or two afternoons per week, always following a morning of Barium enemas with cursory cleaning. When we cardiologists had achieved lead insertion, the free end of the lead was wrapped in a sterile sheet and the patient was placed on a hospital trolley to be transferred to the operating room, around 500 m away, including an outdoor section. The waiting surgeons, led by Harold Siddons, had no grasp of the difficulties we had in lead placement for good stability and often their clumsiness prompted a return to the original laboratory for lead repositioning. So many patients covered 1,500 m by hospital trolley with the bulk of the lead outside the body. We certainly had difficulty in positioning the lead, which was a simple silicone-rubber insulated coil, with a removable stylet, and an electrode tip with no passive or active fixation aids. For a new operator, displacement rates were 25% and for the skilled and experienced this figure fell to 10%, but not lower. Figures remained similar to these until the design of the first passive fixation lead in 1976 by Paul Citron, followed in 1978 by the screw-in lead of Bisping.

Pioneering days

Being a member of the team, I had the opportunity of observing the pioneers at close quarters. Aubrey Leatham had made his name from observations of heart sounds and relating them to their physiological and pathophysiological origins. He was a man who could put his stethoscope on a chest and make an accurate pathophysiological diagnosis in about 20 seconds. It was miraculous to behold for a very young and aspiring cardiologist. Because St. George’s had quickly developed the reputation as the pacing centre of the UK, we were visited by many international greats, including Graeme Sloman, a bright and very talented teacher from Melbourne, Australia. Another was Barouh Berkovits, a talented, but blinkered, electrical engineer who worked for American Optical Corp., where he had designed the first ‘demand’ pacemaker. This device was claimed to sense spontaneous cardiac activity (QRS) and, when sensed, withhold the next stimulus, thus avoiding competitive stimulation, which was feared to promote ventricular tachyarrhythmias. However, the exaggerated fear stemmed from laboratory studies of ischaemic models. By virtue of our very expert and thorough cardiac pathologist, Michael Davies, we learned that the majority of our cases of AVB were not ischaemic in nature.3

Berkovits visited us in July 1968 with one of these new non-competitive pacing devices for implantation. Kanu Chatterjee, the cardiology registrar, and I had the honour of implanting it. Kanu, who later migrated to Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles and then to Moffat Hospital, University of California in San Francisco, delighted in showing Berkovits that radiological screening completely inhibited his pacemaker. Berkovits could not accept this, despite its blatant occurrence. The selected patient for this new device had huge numbers of premature ventricular complexes, as well as AVB. It was, perhaps, a natural assumption that he would be ideal for the device, but he did not prove to be so. He died of intractable ventricular fibrillation during the night following implant. We shall never know whether the pacemaker caused this arrhythmia, as the available, on the ward, electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring was insufficient with no permanent records. On Thursday mornings, pacemaker grand rounds were held at St. George’s, Tooting, Berkovits was invited having attended the implant on the previous afternoon. Upon his arrival in the morning, he was greeted by Kanu returning his pacemaker and explaining the events of the previous night.

There was no love lost between Leatham and Geoff Davies on the one hand, and Berkovits on the other, as a legal case had taken place earlier contesting who had designed the Demand pacemaker. Geoff Davies’ design preceded that of Berkovits, but he lost the case on the basis of a minor technicality. Berkovits departed promptly, with pacemaker in hand, never to return. To his credit, he held no grudge as I later collaborated with him during his time at Medtronic Inc.

Other visiting greats of that time and much later, included J-J Welti from Paris, Seymour Furman from New York, Warren Harthorne from Boston and Vic Parsonnet from Newark, New Jersey. Aubrey Leatham thrived on these academic exchanges, which were inspirational for the juniors, with the pacing field being so small at that time.

It was easy to assume at St. George’s that this was the only hospital in the country implanting pacemakers, but this was not so. An equally pioneering group in Birmingham led by Leon Abrams with technology provided by the battery company, Lucas, was very active, also implanting their device in 1960.4 Their pacemaker was an induction system with the lead connecting the internal coil to the heart and the external coil taped to the skin over the subcutaneous internal coil. With this system, they overcame one major weakness of pacing, battery life. However, they had other problems, which came to my notice as a house physician in Plymouth in 1965. Several patients turned up in extremis having Stokes-Adams attacks one after another. We dealt with this in Plymouth by calling a helicopter which took the poor patient to Birmingham, where the external coil was realigned with the internal, and the patient was immediately returned to health and, by the same helicopter, to Plymouth. Had we known how to make this manipulation, we might have saved much money and trauma for the patient, but we were absolutely forbidden to ‘meddle’ with the special tape called ‘Sleek’ keeping the external coil in place. The Lucas device did, however, have another unique and invaluable strength, which was little applauded at the time; the external pacing device had a heart rate control wheel, which the patient could turn up when, for example, stairs were to be negotiated. As so often happened in early pacing, advantages were combined with major disadvantages. The Lucas device was powered by a large U2 battery. When this was low in power it had to be replaced by the patient (or a carer) involving a period of no pacing. If the patient had to do this alone he/she would have to be quick enough to make the change before consciousness was lost.

Sick patients

Much of this discussion emphasises how sick were the patients. Almost all were strongly pacemaker dependent, i.e. no pacing – no heart beats and syncope following in 5–10 seconds. Today, as pacemaker indications have expanded, this type of patient is rare.

Another early pacing activity was temporary pacing for AVB complicating myocardial infarction (MI). In the mid-1960s coronary care units (CCUs) were being introduced all across the UK. These provided ECG monitoring that could readily diagnose AVB. Pacing seemed to be required, and with an incidence of approximately 8% of CCU cases there were many candidates. St. George’s hospital ran an informal, and not widely advertised, service that necessitated one or more registrar and one or more technician going by car, occasionally with police escort, to the requesting hospital with the necessary leads and external pacemaker. At the time, I was the registrar with the car so I was usually involved, often with Kanu Chatterjee. We went all over London, often during the night to try to achieve pacing for the unfortunate patient. Many were extremely sick and some even died during the procedure, typically those with anterior infarcts.5,6 Procedures were often compromised by the inadequacy of the radiology equipment and, occasionally, we were obliged to work without lead protection for ourselves. With the advent of first thrombolysis, and later primary angioplasty, the complication of AVB in MI has become rare and, at the same time, much more readily dealt with in-house.

The early pacing experience at St. George’s kindled the development of the super-competent cardiac technician, now known as cardiac physiologists. Geoff Davies, the pacemaker designer had started as a cardiac technician. He was quickly regarded as someone special. He later migrated to the company called Devices, as their designer. This company had a premature and dismal fate having been taken over by General Electric of the US; a device powered by the then new lithium battery had an unexpected tendency to explode within the patient. Within a matter of months from its take-over, the Devices company was wound up in 1976. Geoff Davies retired but he left a legacy of very knowledgeable cardiac technicians, which helped to establish this discipline as an important part of cardiology.

By way of example, an early case illustrates the difficulties of pacing in those days. One of the first 50 patients to be paced permanently at St. George’s had much more than her share of procedures. She presented again with a failed pacing system, which was too complicated to fix easily, so temporary pacing was required to allow time for planning. In 1968, we were unable to perform the Seldinger technique7 to introduce a pacing lead. It had been published in 1953 but had not penetrated widely from arteriography, and we had not read about it. So we had to rely on venous cut-down. This lady had lost all of her accessible veins to previous procedures giving us a great challenge. We tried many veins without success, eventually finding one that led to the heart, which we reached after working for 13 hours. Kanu Chatterjee and I believe that this is a skin-to-heart record time! Kanu has been mentioned many times in this memoir, as is obvious we worked together. He was born in India and migrated to the UK where he was not always treated well because of his origin. He realised that he might be better accepted in the US. This proved to be so where he reached great prominence as wise clinician and wonderful teacher.

The paucity of references offered in this memory of early days in pacing, reflects that we were very busy taking care of patients, and our activities antedated the explosion of medical publication. Further, some of the incidents and opinions expressed here could not have been published at the time for reasons of the personalities involved and of the prestige of St. George’s.

British contribution to pacing

The early British contribution to pacing was rather ‘Yes we also can!’

However, later contributions were more substantial. Tony Rickards was a great thinker about pacing. He represented Britain internationally very well. A few of us, Edgar Sowton, Raphael Balcon, Tony Rickards and I established the British Pacing Group (BPG) in 1976 after the fifth world congress in Tokyo that year. Together, we organised the second European congress on cardiac pacing, now known as the Europace meeting, in 1978.

Tony inspired us to create a national database, which was among the first in pacing. This database, over many years after its inception and before the widespread use of databases, provided evidence for several types of device failure ahead of companies discovering the faults of their own devices. Further, Tony devised a type of rate responsive pacemaker – the QT.8 He recognised that the paced QT-interval changed with heart rate requirement and that this could be used to adapt the rate of the device to the body’s needs. It was a brilliant idea, but it was later supplanted by simpler, faster-reacting sensor systems. Tony was a very skilled operator and combined with his brilliant brain he was an extremely effective operator in difficult pacemaker cases. A patient could be in no better hands.

Edgar Sowton was a pioneer and leader of British pacing. Edgar had an electrical engineering background, which stood him on very strong ground in pacing. He worked with Aubrey Leatham as senior registrar before moving to the National Heart Hospital to lead pacing there. His thesis, dedicated to pacing, and later his textbook, written with Harold Siddons, was the reference work on pacing around the world at the time.9 He was a great teacher and supporter of trainees, which was not a universal phenomenon in the sixties and seventies. Edgar represented the UK in the International Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology Society, now known as the World Society of Arrhythmias (WSA). I was fortunate in being nominated by Edgar to succeed him in this capacity. Both Tony and Edgar died tragically early and would, undoubtedly, have achieved more for UK pacing had they lived longer.

Now, as the invited writer of this review and memoir I am obliged to make a personal assessment of my contribution on behalf of the UK. I was appointed a consultant at Westminster Hospital, London in 1976. This hospital already had one cardiologist who had been academically inactive for many years, and it had poor cardiac surgery with a very high procedural mortality. On the plus side, it had one, and potentially a second, cardiac laboratory supported by a first-rate clinical measurement team. My colleague consultant proved willing to intervene administratively on my behalf. So I thought that, with some background in pacing, I should try to establish this as my sub-specialty. I was recruited, the same year, as a consultant to Medtronic Inc., which gave me access to some new technology, an opportunity I seized with both hands.

On this basis, a thriving pacemaker unit was built with many outstanding fellows in training: to name only a few – Rose Anne Kenny, John Perrins, Adam Fitzpatrick and Panos Vardas. This group pioneered dual chamber pacing,10 and introduced tilt testing as a means of precipitating syncope in front of medical witnesses and with non-invasive haemodynamic monitoring.11 The latter revolutionised the study of syncope, with many positive consequences. As a result of leading this active group, I was honoured to be the Chairman of the European Working Group on Cardiac Pacing, which is now part of the European Heart Rhythm Association.

In conclusion, UK pacing, has played an important part in the international development of pacing. We were fortunate that at the time when cardiac pacing first emerged, there were already energetic, distinguished and innovative cardiologists, cardiac surgeons and electrical engineers on hand to advance the frontier of this important life-saving therapy.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to my friend and colleague, David Benditt of Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, for reading this paper and appraising it from an international perspective.

Key messages

- Early days of any medical procedure or therapy tend to be fraught with difficulty

- Early days of pacing were conspicuous for their innovation and coalescence of brilliant active people

- The UK made a significant contribution to the worldwide development of pacing

Conflict of interest

RS is a consultant to Medtronic Inc.; a grant holder from Medtronic Inc. for the Syncope Prediction Study; a member of the speakers’ bureau for Abbott Laboratories; and a shareholder in AstraZeneca PLC, Boston Scientific Inc and Edwards LifeSciences Corp.

Articles in the Pacing supplement

Introduction

Current and future perspectives on cardiac pacing

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy – developments in heart failure management

Drugs with devices in the management of heart failure

His-bundle pacing: UK experience and HOPE for the future!

Leadless pacing

Techniques in pacemaker and defibrillator lead extraction

Remote monitoring

Remote follow-up of ICS: a physiologist’s experience

References

1. Sutton R, Davies JG, Leatham AG, Siddons AHM. Five year follow-up of patients paced for complete heart block. Proceedings 5th Eur Congress Cardiol 1968;349.

2. Campbell M. Complete heart block. Br Heart J 1944;6:69. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.6.2.69

3. Davies M, Harris A. The pathological basis of primary heart block. Heart 1969;31:219–26. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.31.2.219

4. Abrams LD, Hudson WA, Lightwood R. A surgical approach to the management of heart-block using an inductive coupled artificial cardiac pacemaker. Lancet 1960;275:1372–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(60)91151-X

5. Sutton R, Chatterjee K, Leatham AG. Heart block following acute myocardial infarction; treatment with demand and fixed-rate pacemakers. Lancet 1968;292:645–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(68)92502-6

6. Sutton R, Davies MJ. The conduction system in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1968;38:987–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.38.5.987

7. Seldinger SI. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiol 1953;39:368–76. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016925309136722

8. Rickards AF, Norman J. Relation between QT interval and heart rate. New design of physiologically adaptive cardiac pacemaker. Br Heart J 1981;45:56–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.45.1.56

9. Sowton E, Siddons H. Cardiac pacemakers. Springfield, Illinois, USA: Charles C Thomas Publishers Inc., 1967.

10. Sutton R, Perrins EJ, Citron P. Physiological cardiac pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1980;3:207–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1980.tb04331.x

11. Kenny RA, Ingram A, Bayliss J, Sutton R. Head-up tilt: a useful test for investigating unexplained syncope. Lancet 1986;327:1352–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91665-X