A 52-year-old man, previously fit and well, presented with myocardial infarction complicated by ischaemic ventricular septal defect (VSD) and acute right ventricular failure, was successfully treated with early percutaneous coronary reperfusion, surgical VSD repair and temporary right ventricular assist device (VAD) support.

This case is an example of how a modern healthcare system can successfully manage complex emergency cases, combining high levels of clinical care and medical technology. Access to temporary mechanical support played a vital role in this case. We believe that wider access to VADs may contribute to improvement in the, widely recognised, poor outcome of ischaemic VSD.

Introduction

Post-myocardial infarction VSD is an uncommon but frequently fatal complication, occurring in less than 1% of patients sustaining myocardial infarction (MI) in the modern era of early reperfusion therapy. Despite significant improvements over the last two decades in overall mortality for acute MI, the outcome of patients who develop VSD remains poor. Mortality rates exceed 90% with medical therapy.1,2 Data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) registry (2,876 patients) showed an overall operative mortality of 42.9%, representing the highest risk of all cardiac procedures recorded in the database. Mortality was higher (54.1%) if repair was ≤7 days from MI. An intra-operative VAD was placed in just 2.9% of the STS patients.3 The data detailing the success of VAD strategies in the management of ischaemic VSDs are currently limited to case reports.2

Case

A 52-year-old man, previously fit and well, was admitted with inferior ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and history of two weeks’ angina. Late presentation at hospital was due to severe anxiety. The acute coronary syndrome pathway was activated and the patient received stenting (PROMUS ElementTM, Boston Scientific) of an occluded right coronary artery (door-to-balloon time 30 minutes). The course was complicated by clinical deterioration overnight, a transthoracic echocardiogram showed inferior VSD and severely compromised right ventricular (RV) function. Dobutamine infusion was started to manage severe hypotension. The case was promptly referred for emergency surgical repair (referral-to-surgery time less than three hours).

On arrival in theatre the patient was tachycardic (heart rate 120 bpm), with blood pressure 101/76 mmHg and a lactate level of 5 mmol/L.

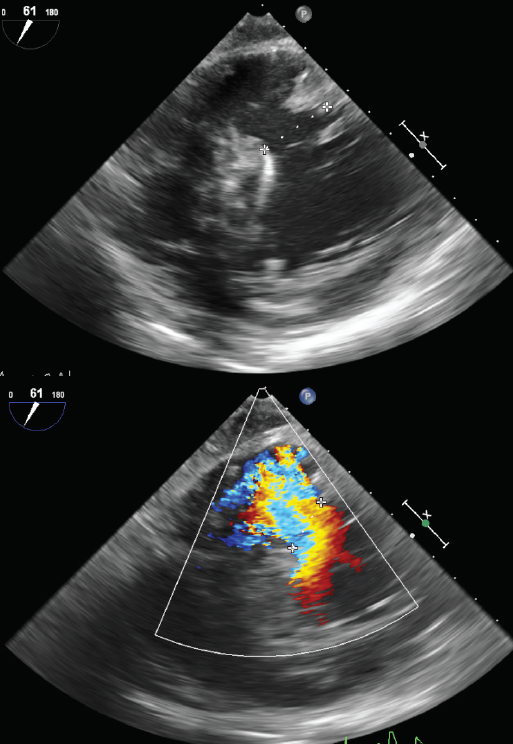

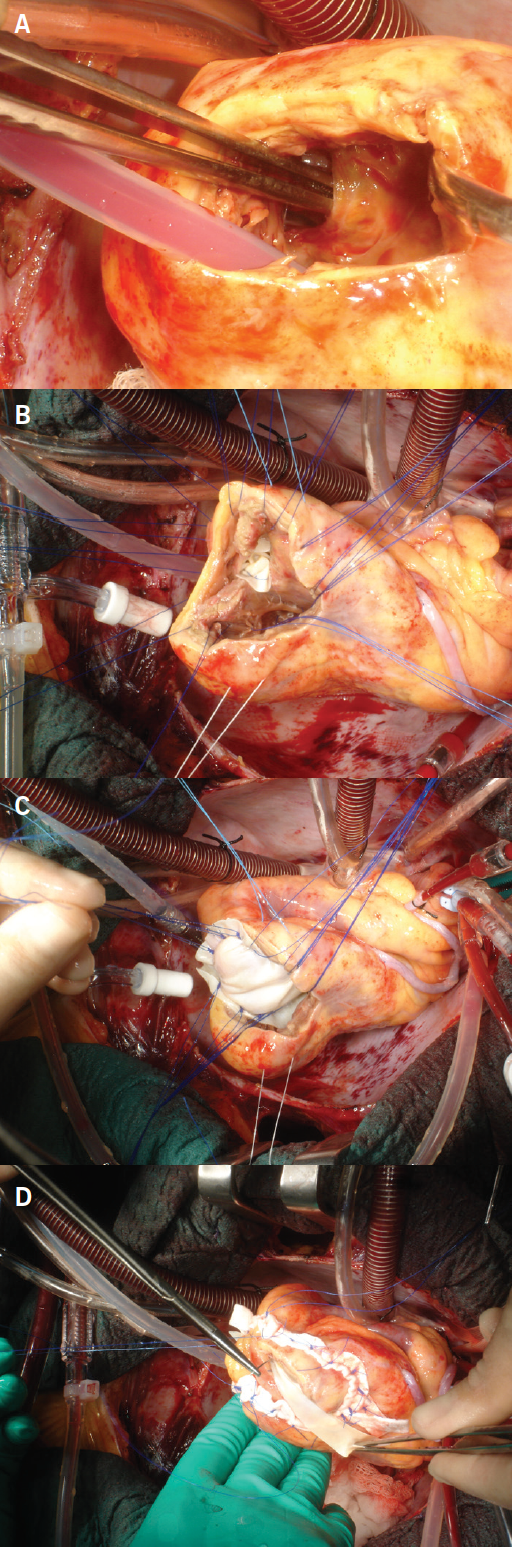

Intra-operative transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) confirmed the characteristics of the defect and guided the repair (figure 1). A closure of the VSD with a double bovine pericardial patch technique was performed (figure 2).4 In view of the acute RV failure, the patient was electively weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass to RV assist device (RVAD, CentriMag VAD Levitronix) and an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was placed to support the left ventricle.

The first 24–48 hours in intensive care required inotropic support (milrinone, adrenaline, levosimendan), RVAD, IABP, TOE monitoring, inspired nitric oxide and renal replacement therapy. The haemodynamic and metabolic state improved, and three days post-surgery (Saturday) a first trial of weaning from the RVAD support was performed with encouraging results. A second trial was repeated the following day (Sunday), the TOE confirmed satisfactory recovery of the ventricular function and pericardial collection, the RVAD was explanted and the pericardial cavity re-explored. The IABP was removed the following day. Three days post-extubation the patient developed respiratory fatigue, aggressively treated with semi-elective bronchoscopy, tracheostomy and bilateral chest drain insertion. Twenty-three days after VSD repair the patient was transferred to the ward and discharged home on day 27. Psychological support was offered and the involvement of the patient’s family played a fundamental role in supporting his severe anxiety and post-operative progress.

Three-month clinical follow-up confirmed good biventricular function and excellent post-operatory functional recovery.

Discussion

We strongly believe that the results achieved in this case are due to the efficiency of the entire care pathway. Cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, anaesthetist and intensivist consultants led all steps of the medical management. Weekend consultant-delivered care and 24-hour specialist registrar cover were guaranteed. Specialised intensive care nurses managed a complex recovery. Emergency pathways were promptly activated and complications (such as acute RV failure, VSD, respiratory fatigue) were recognised early and aggressively treated. Additional to the great team effort, access to modern medical equipment was vital. In particular, we believe that the decision to electively wean the patient from cardiopulmonary bypass to right VAD played a paramount role in the successful management of the acute RV failure and in the patient’s outcome.

Acute RV failure is associated with high mortality, despite optimal medical management, and implantation of a RVAD is an option in critical patients.5,6 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recognise the role of VADs as a bridge to cardiac transplantation or recovery, and as temporary support for cardiogenic shock post-cardiac surgery or acute heart attack. The National Health Service (NHS) England currently commissions VADs for bridging to transplantation in designated transplant centres only, but recognises the short-term use in non-transplant cardiac centres, based on a recent meta-analysis showing a 63% survival in patients with post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock. The CentriMag estimated cost per use is £3,542 and high financial pressure makes access to such equipment a challenge for non-transplant centres.7,8

This case is an example of how this technology significantly contributed in saving the life of a young man undergoing emergency ischaemic VSD repair. A wider use of VADs as a bridge to surgery or post-repair support may contribute in improving the current poor outcome of ischaemic VSDs, particularly for patients requiring emergency surgery.

The cost/benefit and clinical advantages of having VADs available in all UK cardiac centres is debatable. Patients in heart failure requiring surgery or transplant candidates definitely benefit from centralisation of care, and should be treated in specialised designed centres. This model of care guarantees the best outcomes and resources utilisation.

However, in a small number of young patients who require emergency/salvage procedures, such as the case reported, or experience unexpected intra-operative complications, the use of post-cardiotomy VAD support may represent the only bail-out strategy and may justify the need for the availability of such devices in non-transplant centres. Lack of local resources and training remains one of the main limitations.

We strongly support the need for VADs and a trained team to be available in experienced cardiac centres as part of a modern healthcare service.

Key messages

- A young patient with ischaemic ventricular septal defect (VSD) and acute right ventricular (RV) failure was treated combining early coronary reperfusion, surgical repair and ventricular assist device (VAD) support

- This represents an example of how a modern healthcare system can successfully manage complex cases combining high levels of clinical care and medical technology

- The use of VAD played a paramount role in this patient’s outcome

- VADs should be available in experienced cardiac centres as part of a modern healthcare service. A wider use of VADs may contribute in improving the current poor outcome of ischaemic VSDs

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Consent

The patient provided consent for publication.

References

1. Crenshaw BS, Granger CB, Birnbaum Y et al. Risk factors, angiographic patterns, and outcomes in patients with ventricular septal defect complicating acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-I (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Trial Investigators. Circulation 2000;101:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.1.27

2. Jones BM, Kapadia SR, Smedira NG et al. Ventricular septal rupture complicating acute myocardial infarction: a contemporary review. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2060–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu248

3. Arnaoutakis GJ, Zhao Y, George TJ, Sciortino CM, McCarthy PM, Conte JV. Surgical repair of ventricular septal defect after myocardial infarction: outcomes from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:436–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.020

4. Balkanay M, Eren E, Keles C, Toker ME, Guler M. Double-patch repair of postinfarction ventricular septal defect. Tex Heart Inst J 2005;32:43–6. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC555820/

5. Cheung AW, White CW, Davis MK, Freed DH. Short-term mechanical circulatory support for recovery from acute right ventricular failure: clinical outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2014;33:794–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2014.02.028

6. De Robertis F, Rogers P, Amrani M et al. Bridge to decision using the Levitronix CentriMag short-term ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant 2008;27:474–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2008.01.027

7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CentriMag for heart failure. Medtech innovation briefing 92. London: NICE, January 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib92

8. Borisenko O, Wylie G, Payne J, Smith J, Yonan N, Firmin R. Thoratec CentriMag for temporary treatment of refractory cardiogenic shock or severe cardiopulmonary insufficiency: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of observational studies. ASAIO J 2014;60:487–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000000117