Around 7.4 million people in the UK have heart and cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease (CAD) being the most common type. The Driving and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) has guidance for medical professionals to aid assessment of cardiac patients with respect to driving. The guidance is different for personal, Public Carriage Office (PCO) and goods vehicles. It remains the doctors’ responsibility to advise patients of any driving restrictions, as certain cardiac conditions can limit patients’ ability to drive. This gains importance especially after certain procedures. A retrospective review of discharge summaries from electronic medical records was undertaken for a period of three months to review the number of patients getting appropriate advice. It was noted that frequently no written driving advice was recorded on discharge, neglecting an important element of patient safety. Steps were taken to counteract the lack of proper driving advice and documentation, which were effective on second review. Therefore, measures similar to ones outlined here should be put in place to ensure safe discharge and knowledge of the clinicians in accordance with the DVLA guidance.

Introduction

Mr X is a 48-year-old man who was admitted to Accident and Emergency (A&E) with chest pain. He described typical cardiac sounding chest pain, initially on exertion, but at the time of presentation, pain at rest. His electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ischaemic changes, with dynamic troponin rise. He was discussed with cardiology on-call, the impression was non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and he was admitted under the cardiology team for further management. Mr X had an angiogram that showed significant coronary artery disease (CAD) requiring intervention. He had successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and uncomplicated post-procedure recovery. At the time of discharge, Mr X had concerns as he was a lorry driver, would he be able to go back to work and did he need to notify the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA)? This is where the problem arose, as the junior doctors on ward were unaware of the DVLA guidelines.

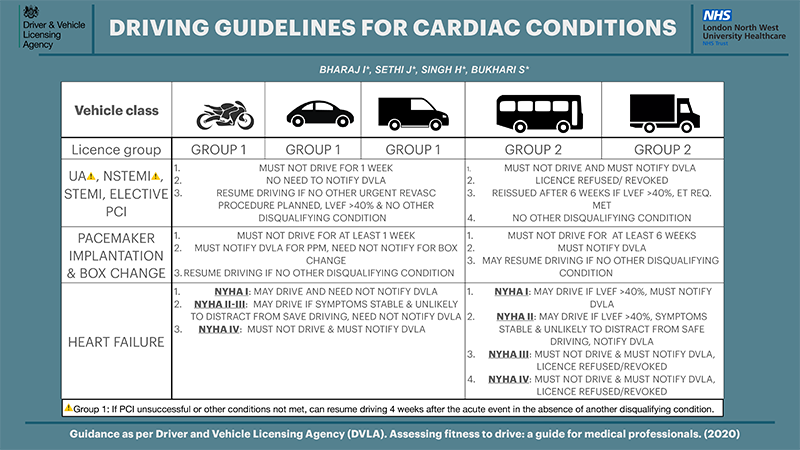

The DVLA publishes detailed guidance for patients and healthcare professionals on medical restrictions to driving in order to safeguard patients, passengers, pedestrians and other drivers. Group I (cars and motorcycles) and group II (heavy goods vehicles, buses and coaches) driving licences exist in the UK, and group II licence holders are subject to more medical restrictions due to the size and weight of the vehicle they drive. It remains the doctor’s duty to educate and inform patients of these limitations, even though patients are legally responsible for notifying the DVLA of any condition that affects their fitness to drive.1 However, knowledge of the DVLA guidelines among healthcare professionals at all stages of their training is limited. As a result of inadequate or absent driving advice, many patients may continue to drive when it is medically unsafe to do so.

As per British Heart Foundation (BHF) facts and figures, heart and circulatory diseases cause more than a quarter of all deaths in the UK, that’s nearly 170,000 deaths each year – an average of 460 deaths each day or one every three minutes.2 Moreover, there are more than 100,000 hospital admissions each year due to heart attacks: that’s one every five minutes. The data from the National Audit for Percutaneous Intervention (2017–18) shows that 118 PCI centres in the UK performed a total of 102,258 PCI procedures in 2017/18, equating to a rate of 1,548 per million population.3 According to current guidelines, patients who recently underwent therapeutic intervention for acute coronary syndrome or pacemaker insertion must not drive for one week following the procedure in the case of a group I licence, and notify the DVLA in the case of a group II licence, with the licence being reissued after six weeks once certain criteria are met.1

Data collection

Ealing Hospital is a 330-bed district general hospital in West London under the London Northwest University Healthcare NHS Trust. The hospital has a functioning cath lab, performing elective inpatient and outpatient angiography and pacing. Under the guidance of a cardiology consultant, data were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records on the cardiology ward from January 2019 to March 2019. Inclusion criteria were patients admitted under the cardiology team having coronary intervention, i.e. PCI. Patients who had a diagnostic angiogram or those for multi-disciplinary team (MDT) discussion for possible coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) were excluded. After anonymising patient identifiers, a spreadsheet was used to record the date of discharge, primary diagnosis, other relevant diagnoses or comorbidities, indication and type of procedure, driving status on admission and presence or absence of driving advice. The measurement during this three-month period included 41 patients. Of these, none of the patients had driving status documented on admission. Furthermore, only 2.4% (1/41) of patients had driving advice documented on discharge summary. To gather the perspective of doctors, anonymised paper questionnaire forms regarding awareness of DVLA guidelines were handed out and completed by 20 junior doctors. While 20% (4/20) were aware of the guidelines, no one recorded driving status on admission. Finally, 100% of responders reported some form of teaching or induction would be very helpful.

Steps toward improvement

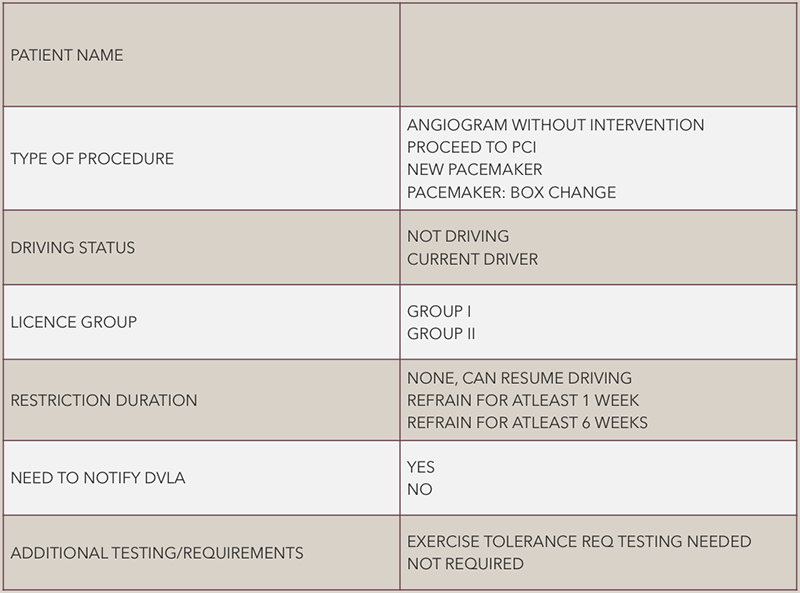

In view of the results, which were quite unsatisfactory, it was felt an intervention was the need of the hour. A plan was formulated to tackle the issue in three parts; first, whether verbal advice at the time of intervention was provided and not documented. This was achieved by discussion with the consultants. Second, to improve the awareness of junior doctors by providing formal teaching and setting up posters (figure 1), which also included advice in other cardiac conditions, including heart failure. Third, documentation of the driving status and driving advice on discharge. A patient information form was created (figure 2), to be filled in by either the cath lab staff or the doctors on the ward, and provided to the patient.

In order to witness the impact of the above measures, a repeat review was done from July 2020 to August 2020. Data were collected from electronic medical records and patient case files in the cath lab. In the period of two months, 33 patients underwent PCI. Of these, 39% (13/33) had the patient information form filled in correctly and supplied. A further four had driving advice documented on the discharge summary and 10 had driving status documented on admission.

Limitations and perspective

The impact from the interventions was a step in the right direction. However, there are certain limitations. First, the data are from a single centre; external generalisability has to be addressed. Second, the sample size is not extensive, rather quite limited. Third, the experience at a larger hospital, or a specialist centre might be different. Finally, as it was noted previously, the driving advice could be provided verbally without documentation. Hence, it was taken into consideration during re-audit.

On literature review for similar studies, two publications stood out. Vusirikala et al., at Southmead Hospital, Bristol, demonstrated the gravitas of this problem as only 10% (9/92) of discharge summaries showed driving advice.4 However, by introducing educational measures and prewritten driving advice for discharge summaries it improved to 49% after the third PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycle. Similarly, a group at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust also introduced a structured template to improve discharge advice given to patients. This intervention increased the provision of driving and flying advice from 3% to 79%.5 While the data remain limited, it is plausible to infer similar results would be seen across the country.

Conclusion

If we follow the trend seen in the number of cardiac interventions, they are expected to continue rising. As clinicians, it is our responsibility to ensure patient safety, which extends beyond the hospital doors once the patient is discharged. To avoid patients putting themselves, or others, at risk by driving when it is medically unsafe, doctors must provide appropriate discharge advice. While more studies and data are required to fully comprehend the extent of inadequate driving advice and failure to follow DVLA guidelines, steps should be taken to rectify this issue to ensure patient safety.

Key messages

- The Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) has guidelines on driving after undergoing cardiac interventions, including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and pacemaker insertion

- As the number of cardiac procedures continues to rise, it is the duty of physicians to ensure driving status is documented and driving advice is provided on discharge

- Steps like posters, forms, induction and teaching for junior doctors would be helpful in raising awareness and ensuring patient safety, while a national audit might shine a light on the issue at a wider level across the country

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

Not required.

References

1. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). Assessing fitness to drive: a guide for medical professionals. Swansea: DVLA, 2016. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessing-fitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical-professionals

2. British Heart Foundation. Heart & Circulatory Disease Statistics 2020. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics/heart-statistics-publications/cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2020

3. British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS). BCIS National audit adult interventional procedures: 1st April 2018 to 31st March 2019. Available from: http://www.bcis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/BCIS-Audit-2018-19-data-ALL-24-01-2020-for-web.pdf

4. Vusirikala A, Backhouse M, Schimansky S. Improving driving advice provided to cardiology patients on discharge. BMJ Open Quality 2018;7:e000162. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000162

5. Mäkelä P, Haynes C, Holt K et al. Written medical discharge communication from an acute stroke service: a project to improve content through development of a structured stroke-specific template. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2013;2:u202037.w1095. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u202037.w1095