We report the case of an elderly woman with recent hip replacement surgery that presented with cardiogenic shock. The initial echocardiogram was suggestive of mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, which was later confirmed due to absence of severe coronary artery disease and complete resolution of the patient’s cardiac systolic dysfunction. Fluid and inotrope administration in the acute phase, and guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure, thereafter, led to full recovery.

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTCM) is an often reversible injury of the myocardium caused by catecholamine excess, usually after a stressor.1 The first case series were described by Tsuchihashi et al. three decades ago, and it was named due to the resemblance of the left ventricle (LV) in ventriculography to a Japanese pot used to catch octopuses. It usually affects post-menopausal women and has a typical form involving the mid and apical segments of the LV (apical ballooning), and atypical forms (mid, basal and focal TTCM).2 Mid-ventricular TTCM is a rare variant that affects the mid-segments of the LV, and accounts for 14.6% of patients presenting with this syndrome.3

Case presentation

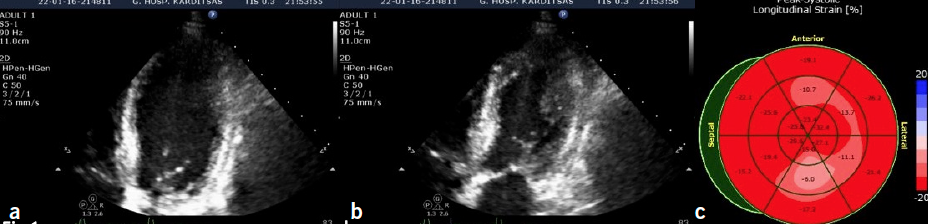

A 71-year-old woman that underwent total hip arthroplasty the day before, after falling from a standing position, presented with hypotension (80/45 mmHg), tachypnoea, and signs of poor peripheral perfusion. The patient’s only pertinent medication included irbesartan 150 mg daily for arterial hypertension. Cardiology consultation was requested. Upon cardiac auscultation an S3 was audible in the left precordium along with bi-basal lung crackles. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was deemed necessary in order to unveil the mechanism behind the cardiovascular haemodynamic collapse in a previously well patient with no history of heart failure (figure 1).

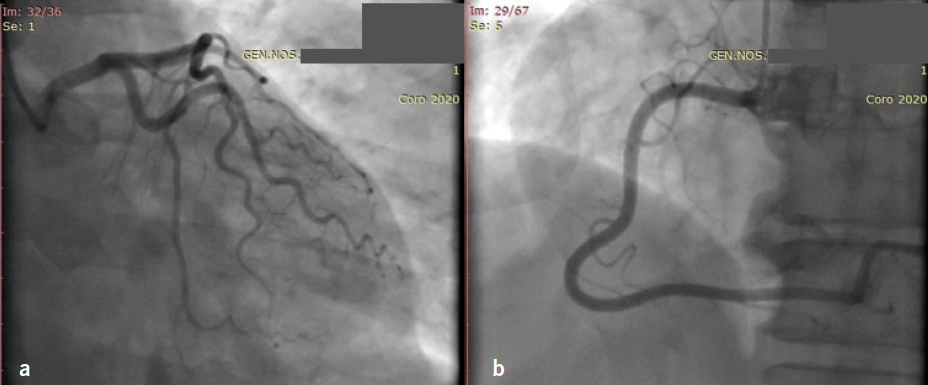

The patient was then transferred to the cardiac care unit with fluid boluses and inotropic support, as no LV outflow obstruction was noted. When haemodynamic stability was ensured, guideline-directed medical therapy commenced, and the patient underwent coronary angiography due to the, presumed new, LV wall motion abnormalities and low troponin rise (figure 2). Surprisingly, the patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG) remained grossly normal throughout her hospital stay.

Keeping in mind the patient’s demographics, physical and emotional stressors, echocardiographic appearance of the LV, low troponin rise and absence of severe coronary artery disease, mid-ventricular TTCM was the final diagnosis, with a probability of 98.8% according to the International Takotsubo registry score (InterTAK score).

The patient was asymptomatic and well, and discharged on carvedilol and ramipril. A re-examination was scheduled three weeks later. A new echocardiogram was performed showing complete resolution of the regional wall motion abnormalities (figure 3).

Discussion

TTCM is known to typically manifest in elderly female patients presenting with chest pain or new-onset heart failure after an emotional stressor. The majority of patients in many series are postmenopausal women between the ages of 60 and 80 years, although younger women and men are also affected.4 The advanced age and risk factors for coronary artery disease in these patients make the diagnosis difficult. One of the main characteristics of this syndrome are the physical or emotional triggers that preclude the presentation of symptoms, making TTCM widely known as ‘broken-heart syndrome’.5,6 Typical anginal chest pain, dyspnoea, syncope or arrythmias are the main symptoms of TTCM,7 which, if combined with ST-segment elevation or depression on the ECG and a, usually modest, rise in cardiac troponin, make the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome very likely at first glance.8 New-onset ischaemic ECG changes are reported to be present in about two-thirds of affected patients in many registries,8 while Tsuchihashi et al. reported ST elevation in 90%.7 Those findings often lead to activation of the cath-lab and, traditionally, epicardial artery stenoses <50% are needed for the diagnosis of TTCM, according to the well-known Mayo clinic criteria.9 However, this remains an area of debate because significant atherosclerotic disease does not exlude TTCM, and those patients may be misdiagnosed as having a myocardial infarction. Acute therapy for TTCM consists of beta-blockade when outflow tract obstruction is present. Use of inotropes are an area of conflict, given the deleterious effects of catecholamines on the heart muscle of those affected. Oral medication is no different to that used for heart failure, and is usually stopped when LV function is restored, due to the low incidence of reccurence.10

Key messages

- This case illustrates the significance of echocardiography in the assessment of patients with acute haemodynamic instability

- In the echocardiographic examination of a severely ill patient, the cardiologist must have a high suspicion for cardiac manifestations of systemic disease, such as catecholamine surge in Takotsubo

- Regional wall motion abnormalities, especially if not in the distribution of an epicardial vessel, should arouse suspicion of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

Written consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

References

1. Wittstein IS. Acute stress cardiomyopathy. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2008;5:61–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-008-0011-3

2. Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A et al. International expert consensus document on Takotsubo syndrome (part I): clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2032–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy076

3. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015;373:929–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1406761

4. Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2008;124:283–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.002

5. Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:333–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.057

6. Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1523–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032

7. Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T et al. Angina pectoris-myocardial infarction investigations in Japan. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01316-X

8. Dib C, Asirvatham S, Elesber A, Rihal C, Friedman P, Prasad A. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of electrocardiographic abnormalities in apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo/stress-induced cardiomyopathy). Am Heart J 2009;157:933–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.023

9. Scantlebury DC, Prasad A. Diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2014;78:2129–39. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0859

10. Bybee KA, Prasad A. Stress-related cardiomyopathy syndromes. Circulation 2008;118:397–409. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.677625