Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes), previously known as Propionibacterium acnes, is a rare cause of infective endocarditis (IE). We provide a review of the literature and describe two recent cases from a single centre to provide insight into the various clinical presentations, progression and management of patients with this infection.

The primary objective of our review is to highlight the difficulty in the initial assessment of these patients with an aim to improve the time and accuracy of diagnosis and expedite subsequent treatment. There are currently no guidelines in the literature specific to the management of IE caused by C. acnes. Our secondary objectives are to disseminate information about the indolent course of the disease and add to the growing body of evidence around this rare, yet complex, cause of IE.

Introduction

The incidence of Cutibacterium acnes as the causative organism for infective endocarditis (IE) is reported as 0.3%.1 C. acnes IE is associated with both native and prosthetic valves, but is much more commonly found on prosthetic valves. Studies show that middle-aged men are mostly affected, with serious infections increasingly reported in association with bioprosthetic material.1 C. acnes is part of the commensal flora of the skin, colonising pilous follicles and sebaceous glands, and may also be found in the mucosa of the mouth, nose, urogenital tract and large intestine, this difference might account for the gender-specific bacterial colonisation and subsequent male predominance seen in C. acnes infections.2 In a more recent study, the proportion of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) cases due to C. acnes was nearly three times that previously reported from the International Collaboration on Endocarditis – Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) (23/606, 3.8% vs. 13/923, 1.4%).1,3

The increasing incidence of C. acnes endocarditis may, in part, be secondary to the increasing number of prosthetic valves being inserted, or be a product of increased diagnosis due to the use of valve sequencing via PCR (polymerase chain reaction).4 In addition, patients with C. acnes IE usually have advanced disease by the time they present, with a substantial proportion of patients having invasive disease and embolic complications.1 There typically is a delayed presentation, in one case series, the mean onset of infection was four years from surgery.5

The mortality rates due to C. acnes IE have been described in one recent study as 16%.5 This may be due to the prevalence of C. acnes associated PVE, late diagnosis and subsequent delay in targeted treatment of the disease.1 Herein, we present our experience of two patients affected by C. acnes associated IE.

Case presentations

Case 1: 29-year-old man with three re-do aortic valve replacements

A 29-year-old man, with a known congenital bicuspid aortic valve underwent minimal access aortic valve replacement (AVR), receiving a mechanical (25 mm On-X) prosthesis in November 2015.

A routine postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) three months later showed two distinct jets of moderate aortic regurgitation (AR), one of which was paravalvular. A subsequent transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) showed good left ventricular (LV) systolic function with moderate-to-severe paravalvular AR, and he was referred once more for a surgical opinion. In the interim, the patient presented to the emergency department (six months following his original AVR) with a two-day history of rigors and a fever of 40.4 degrees Celsius. Two sets of blood cultures, taken 24 hours apart, were reported as negative in the initial 48-hour period. These cultures were observed for a further eight days as per trust policy in suspected IE with no identifiable growth. The patient was admitted under the medical team and, following satisfactory routine bloods, chest X-ray and electrocardiogram (ECG) tests, was discharged home, with advice to seek medical attention if he developed any further symptoms.

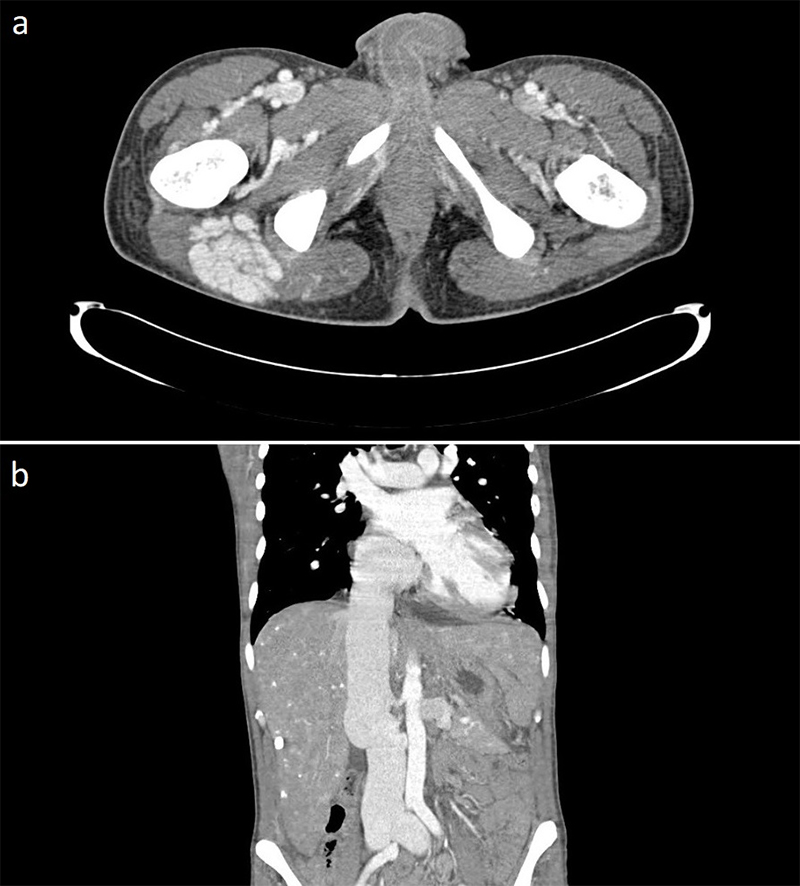

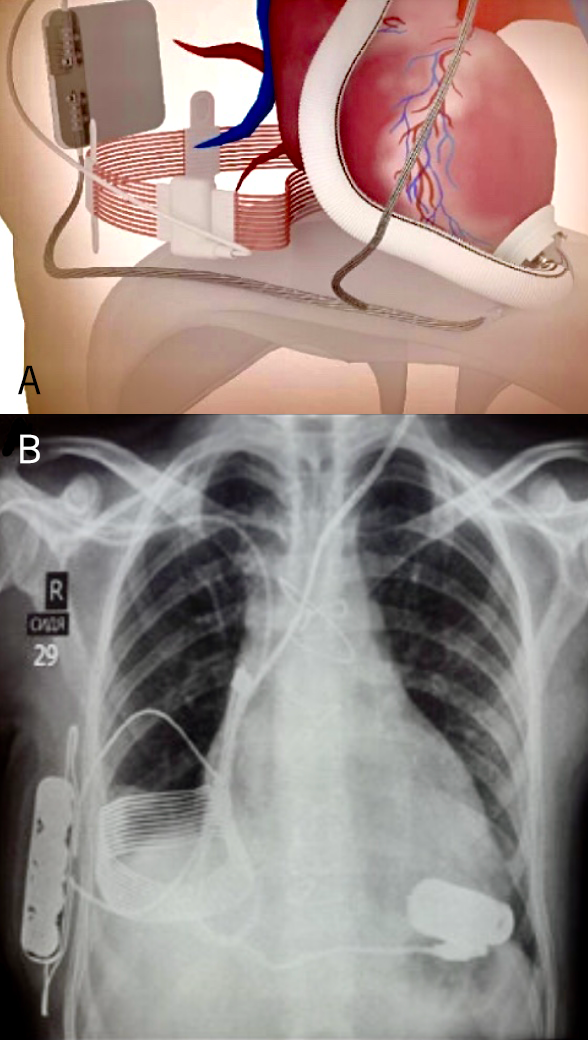

He had intermittent rigors for several weeks following discharge, however, when reviewed by his general practitioner (GP) all observations were recorded to be within normal parameters. The patient was readmitted to hospital due to progression of his symptoms of general malaise and intermittent rigors. A full blood count on this occasion showed a raised white cell count 14.9 × 109/L (WCC) and C-reactive protein (CRP) 96 mg/L, blood cultures were taken. He had a known penicillin allergy, and so the patient was treated with empiric antibiotics as per trust guidelines (table 1). The anaerobic blood culture on this admission was positive for C. acnes. A repeat TOE showed a large vegetation measuring over 3.3 cm2 on the aortic valve causing mild-to-moderate obstruction of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) (figure 1). Furthermore, he had a large aortic root abscess and new ECG findings of a prolonged PR interval with right bundle branch block.

Table 1. Case 1 antibiotic regimen

| Admission 1 | |

|---|---|

| Vancomycin 1 g IV BD 6 days | Vancomycin 1.5 g IV BD 1 day |

| Rifampicin 600 mg PO BD 7 days | |

| Gentamicin 80 mg IV BD 7 days | |

| Re-do operation | |

| Vancomycin 1.5 g IV BD 4 days | Vancomycin 3 g IV continuous infusion 3 doses |

| Rifampicin 600 mg IV/PO BD 7 days | |

| Gentamicin 80 mg IV BD 2 days | |

| Cefuroxime 750 mg IV 3 doses | |

| Discharged home | |

| Daptomycin 500 mg IV OD 5 weeks | |

| Admission 2 | |

| Vancomycin 1 g IV BD 3 days | Vancomycin 1.5 g IV continuous infusion 5 days |

| Rifampicin 600 mg PO BD 8 days | |

| Gentamicin 80 mg IV BD 9 days | |

| Re-do operation | |

| Ceftriaxone 2 g IV OD 6 weeks | |

| Admission 3 | |

| Ceftriaxone 2 g IV OD 8 weeks | |

| Key: BD = twice daily; IV = intravenous; OD = once daily; PO = per oral | |

The patient underwent an emergency re-do aortic valve replacement with a Sorin, Bicarbon 23 mm mechanical prosthesis. Intra-operatively, there was a large vegetation in the outflow tract with areas of abscess under the right and non-coronary cusps. There was a further cavity below the non-coronary cusp which was obliterated with 4-0 prolene.

The patient came off cardiopulmonary bypass and had an uneventful recovery. Intra-operative valve tissue sample was subjected to 16S rDNA real-time PCR and confirmed as C. acnes. The patient weighed 76.5 kg. Once discharged home the patient was continued on antibiotic therapy in the community (table 1).

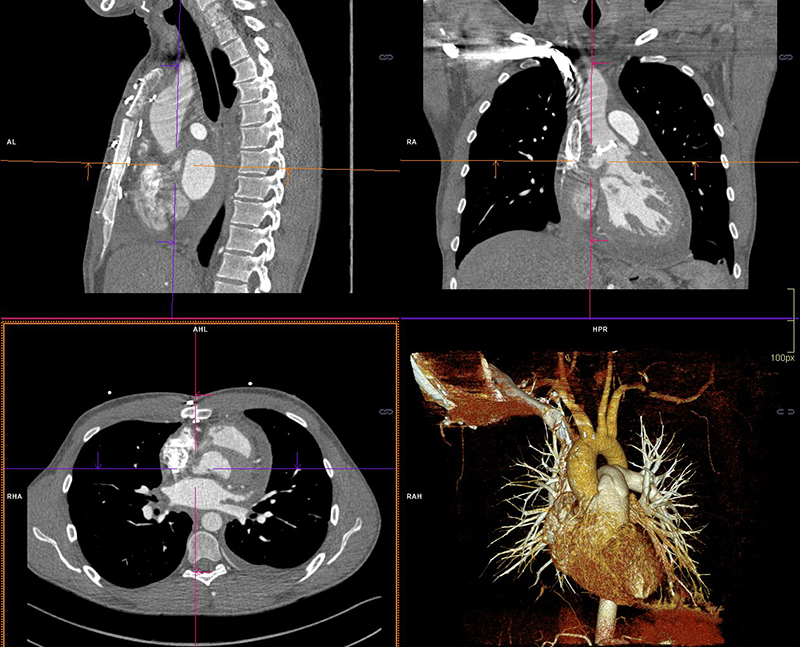

Three weeks following completion of intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy he re-presented with chest pain, shortness of breath and general malaise. A full blood count showed a WCC within normal ranges but a raised CRP of 210 mg/L. Blood cultures grew C. acnes and he was recommenced on antibiotic therapy (table 1). Further cardiothoracic imaging was necessary and an ECG-gated computed tomography (CT) of the thorax showed an irregular and slightly dilated aortic root with a small focal outpouching, in keeping with a small aortic root abscess (figure 2). The patient had several episodes of supraventricular tachycardia managed with adenosine. Following a multi-disciplinary team discussion, the next operation deemed appropriate would involve a homograft replacement, and the patient was transferred to an appropriate surgical centre specialising in adult congenital surgery.

The third operation was uneventful. During this re-do operation, the aortic valve showed evidence of dehiscence along the non-coronary cusp (NCC) with evidence of a chronic large abscess below the NCC onto the anterior mitral valve leaflet (AMVL), there was no evidence of pus intra-operatively. The abscess was debrided and cleaned, and a 27 mm Perimount Magna tissue aortic valve was inserted using interrupted 2/0 ethibond sutures.

Postoperatively, a gated contrast-enhanced thoracic CT was performed to examine the area adjacent to the NCC. It showed a blind ending 15 mm outpouching from the LVOT adjacent to the interatrial septum, with a thin extension posterior to the annulus. There was no visible communication to the ascending aorta or evidence of vegetation or valvular dehiscence. He made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home 15 days later to complete a prolonged antibiotic course for six weeks from date of operation (table 1).

Fourth readmission to hospital

Unfortunately, the patient re-presented to hospital for a fourth time two weeks after his third operation with symptoms of fever and night sweats. A repeat TOE showed no evidence of valvular compromise, no dehiscence and no obvious vegetations on aortic valve leaflets. Furthermore, a positron-emission tomography (PET) scan was performed and excluded an aortic root abscess and any active signs of active focal infection. The patient had a further course of antibiotics and completed a total of eight weeks’ treatment.

Follow-up

One year later, the patient reported feeling well in himself. Reassuringly, a repeat TOE showed no evidence of aortic regurgitation and he continues to be monitored closely in a clinical setting.

Case 2: 74-year-old man with heart failure and urosepsis

A 74-year-old man, with no known allergies to antibiotics, underwent a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in 2014. He had a trans-urethral resection of the prostate (TURP) one year later and required readmission eight weeks following this for treatment of urosepsis. This patient had multiple subsequent admissions for management of sepsis and exacerbations of his heart failure. It was noted that during this time C. acnes grew on a set of blood cultures, but was considered a skin contaminant.

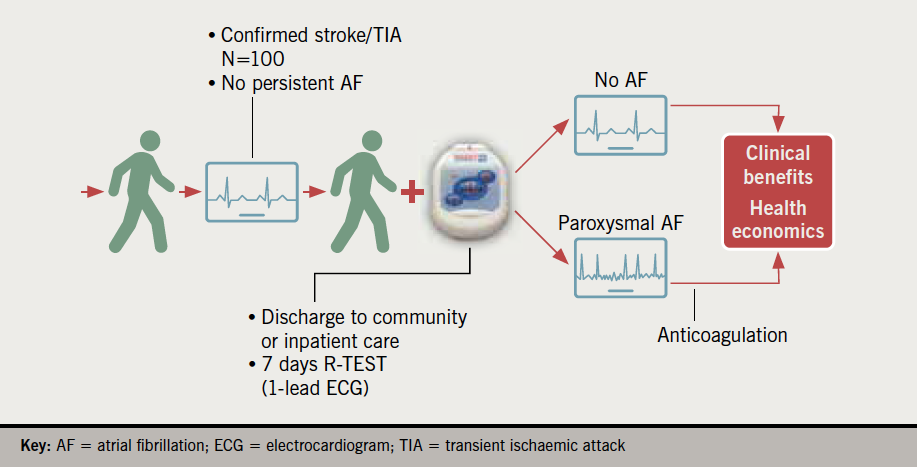

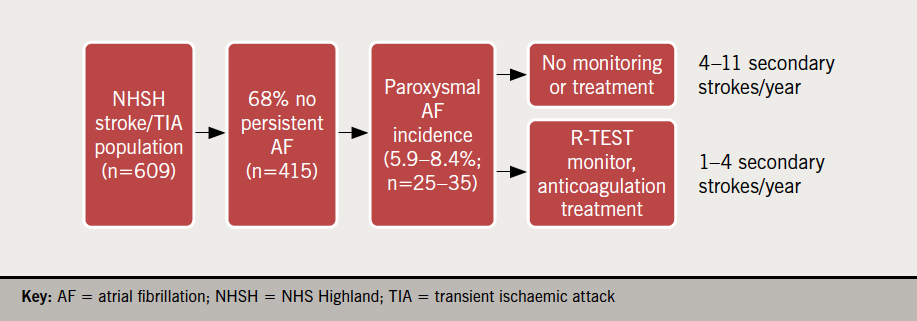

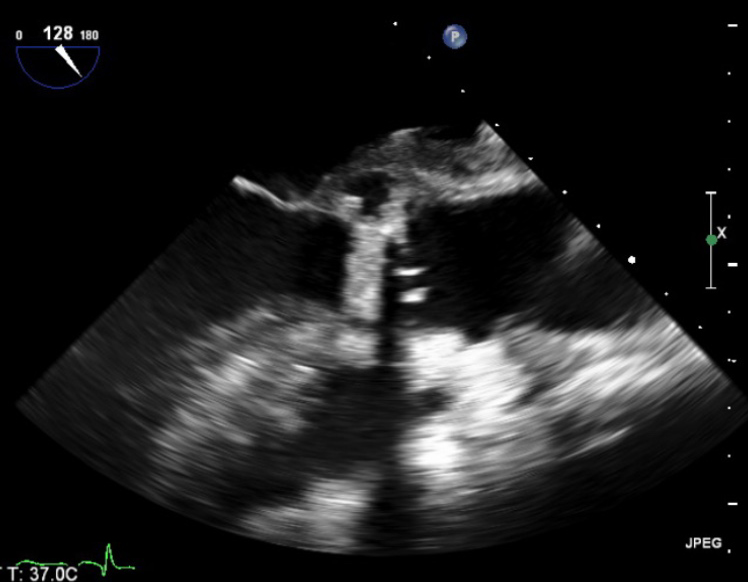

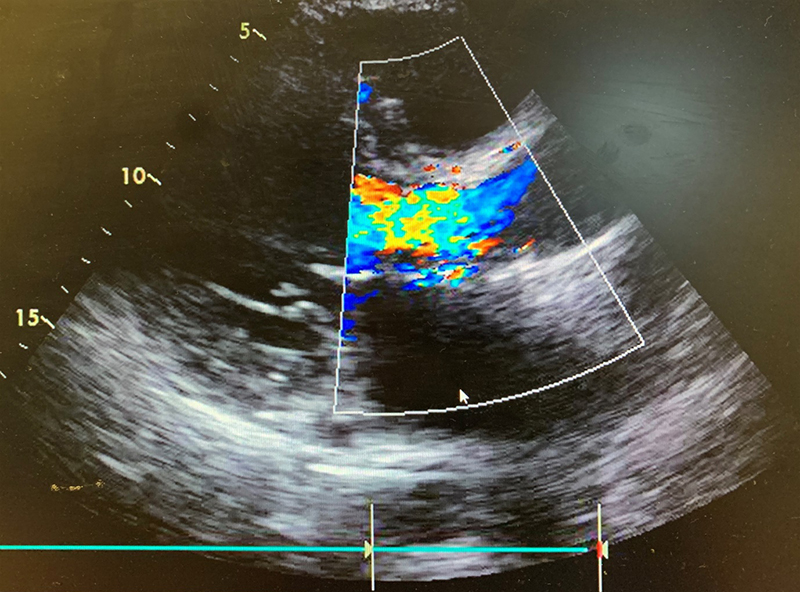

He was seen frequently in a heart failure clinic and optimised on diuretics, however, his symptoms continued to deteriorate. Following a TTE and TOE, he was referred as an outpatient to cardiothoracic surgeons with severe paravalvular aortic regurgitation and a dilated left ventricle with moderate-to-severe systolic impairment (figure 3).

An outpatient ECG-gated thoracic CT showed small outpouchings at the aortic root, possibly in keeping with micro abscesses. He was subsequently admitted from the outpatient clinic with evidence of acute heart failure with ongoing orthopnoea, and persistent episodes of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea. He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for pre-operative optimisation with IV furosemide and dobutamine.

While on dobutamine he had a repeat TOE, which showed moderate ventricular function with mild tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and no evidence of mitral regurgitation (MR). There was also a marked reduction in the left ventricular end diastolic diameter (EDD). His previous TTE had suggested an EDD >7 cm with poor LV function and severe MR and TR. Due to this improvement with dobutamine, the decision was taken to proceed with surgery for severe aortic regurgitation.

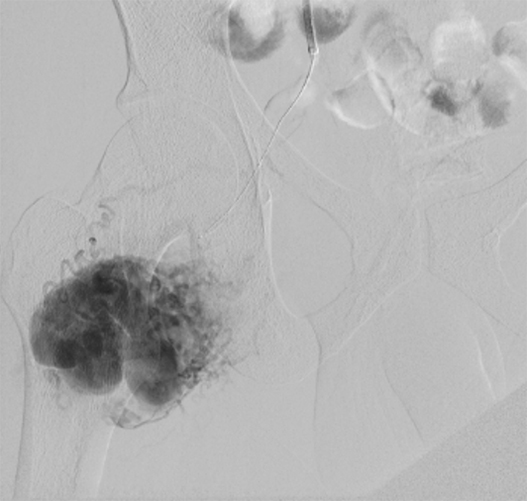

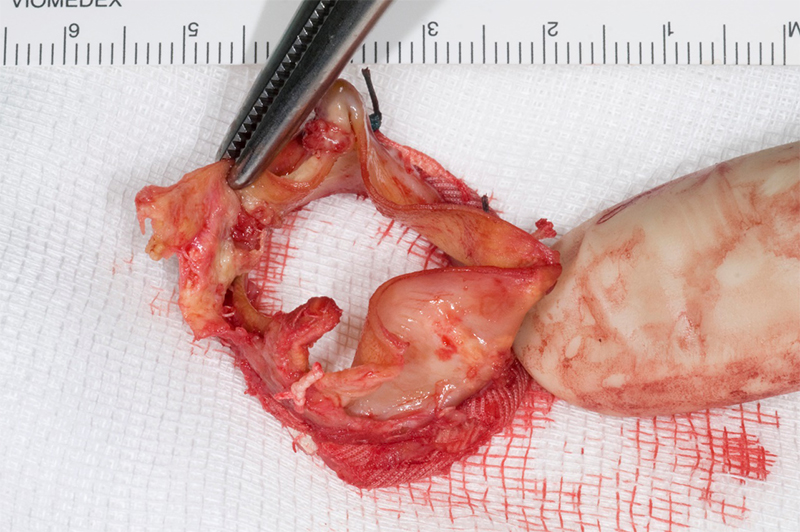

Intra-operatively, there was destruction of the strut at the NCC/right coronary cusp (RCC) junction with dehiscence of the leaflets from the valve frame, leading to the prolapse of the NCC leaflet (figure 4). A new size 23 mm trifecta biological prosthesis was inserted using interrupted plegeted Ethibond sutures × 11. The excised valve was sent for microbiology PCR examination, the 16S rDNA real-time PCR identified C. acnes. Blood cultures were negative.

The patient spent four days in the cardiac intensive therapy unit (CITU) and was gradually weaned off IV dobutamine and furosemide infusions. He developed postoperative delirium and an acute-on-chronic kidney injury requiring haemofiltration for two days. Two weeks following his valve replacement he was repatriated to his district general hospital for further rehabilitation. An antibiotic protocol was detailed on discharge and PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) line inserted to facilitate a regimen of benzylpenicillin 2.4 g IV four times daily for two weeks, then changed to ceftriaxone 2 g IV once daily for four weeks.

Microbiotica

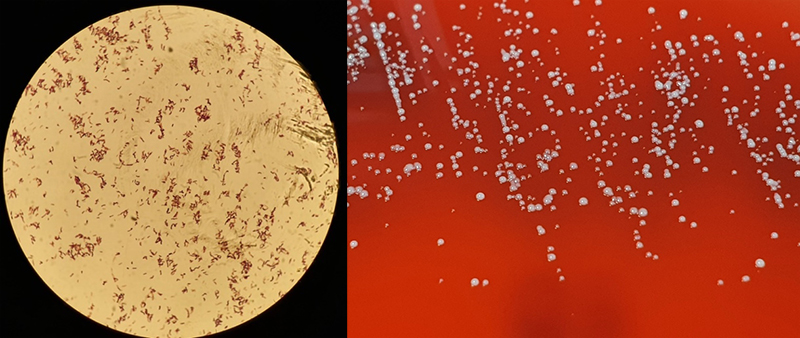

Cutibacteria (formerly propionibacteria) are part of normal flora of human skin and mucosal surfaces. They are slow growing, anaerobic yet aerotolerant, Gram-positive, non-spore forming, pleomorphic rods (figure 5) of relatively low virulence. Cutibacteria, due to their commensal presence on skin and low virulence, are commonly considered contaminants of blood cultures. Infrequently, they can cause significant infections of orthopaedic prosthesis, endovascular devices and cerebrospinal shunts.6

Culture

Given the rarity of IE secondary to C. acnes, and that this bacterium is commonly grown as a commensal, it is pertinent to distinguish between simple culture contamination and a true bacteraemia. Multiple blood cultures must be positive with the same isolate to consider this the causative organism of infection.3 The time to detection of the bacteria in blood cultures is 6.4 days in anaerobic bottles and 6.1 days in aerobic bottles.3 However, the general consensus from numerous studies is, to reduce false negatives, cultures should be incubated for 10 to 14 days.3,7,8 Banzon et al. elucidated that C. acnes is identified in only 12.5% of routine blood cultures, greater success is achieved with extended incubation of blood cultures to 75%.9 However, the gold standard of identifying C. acnes is valve sequencing – PCR base diagnosis targeting 16S rDNA – achieving growth in 95–96% of cases.9,10 Notably, 46% of cases in Banzon et al.’s study, would have found no cause for IE without valve sequencing.9

Clinical course

Time from symptoms, including fever, chill, malaise, fatigue, myalgias and weight loss, to diagnosis averages at four weeks, however, this has been reported to be as long as 32 weeks in some studies. The bacterium can remain intracellular for weeks and months, explaining the long incubation period.11 Given the subtle nature of presentation, delayed incubation period and possibility of skin commensal contamination in blood cultures; diagnosis and subsequent early intervention can present a significant challenge to a clinician.3,4,12 A clear demographic has been shown: C. acnes IE is typically found in middle-aged men. The median age of diagnosis is 52 years, with various studies reporting between 90% and 98% of cases being male.5,7 However, the time from valve/device insertion to diagnosis of cutibacteria IE is less clear, with an average of four years and range between three weeks to 23 years.5 C. acnes has been associated with both native and prosthetic valves, however, the incidence is much higher in the latter.3,4 PVE or IE on an annuloplasty ring accounts for 96% of cases.9 The aortic valve is involved in the majority of cases (71%), mitral valve less so, with involvement in 24% of cases. Tricuspid valve involvement is uncommon (3%).5

Investigations and findings

In our cases, C. acnes has been found to be the causative organism for IE in both men, both of whom have prosthetic valves in situ, all with extensive valve or annulus destruction or abscess formation. Reinforced by the findings of Corvec, C. acnes causes extensive decalcification, abscess formation and valvular destruction.12 These cases displayed systemic symptoms; this is typical in 75% of cases. Case 1 presented primarily with a normal white blood cell count, it was not until his second presentation to hospital that he displayed leucocytosis and, indeed, leucocytosis is typical in only 57% of cases.5 Careful attention to the history, and consideration of potential sources of C. acnes seeding, should be considered. A recent study evaluated the rate of cardiac device-related endocarditis at 1.9 per 1,000 device-years.13 Typical complications of C. acnes include peripheral emboli in 16%, brain emboli in 10%, myocardial abscess in 36% and valvular insufficiency in 52%.5 Complications such as invasive disease (71%) and embolic complications (29%) are common.4,9

Management

Braun et al. strongly recommend a treatment combination of rifampicin with daptomycin or penicillin G.11 The combination of rifampicin and ciprofloxacin might be a reasonable alternative with excellent oral bioavailability for maintenance therapy in complicated IE.11 The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) has set breakpoints for benzylpenicillin, advocating the use of benzylpenicillin instead of vancomycin or ceftriaxone.8 The dose and addition of rifampicin in PVE remains to be elucidated.8

Conclusion

In summary, IE is a disease of high morbidity and mortality. Specifically, with C. acnes as a causative organism, it can be difficult to diagnose, and when established on a prosthetic valve it is very malignant to treat. The initial treating clinician’s awareness and willingness to consider the diagnosis should be encouraged. Once there is an index of suspicion, this should be preserved and the diagnosis pursued with combined modalities such as echo, CT and blood cultures. Due diligence from the multi-disciplinary team is essential in distinguishing between blood culture contamination and a true bacteraemia secondary to C. acnes. The awareness of this pathogen must be highlighted in the greater cardiothoracic and microbiology community in an effort to expedite appropriate treatment and improve patient outcomes.

Key messages

- Infective endocarditis secondary to Cutibacterium acnes is an interesting clinical issue, as it is frequently grown in blood culture and discounted as a skin contaminant. In this clinical setting it should be considered significant and pursued aggressively, given the high rates of severe complication

- Similarities in demographics, including age, gender and a prosthetic aortic valve in this cohort, should be noted and increase the physician level of suspicion when faced with this clinical presentation

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

In accordance with local guidelines of the ethics commission, no ethical application was needed. Institutional review board approval was not required.

Patient consent

Consent was gained from the patients.

References

1. Lalani T, Person AK, Hedayati SS et al. Propionibacterium endocarditis: a case series from the international collaboration on endocarditis merged database and prospective cohort study. Scand J Infect Dis 2007;39:840–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365540701367793

2. Patel A, Calfee RP, Plante M, Fischer SA, Green A. Propionibacterium acnes colonization of the human shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009;18:897–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2009.01.023

3. Achermann Y, Ellie J, Goldstein C, Coenye T, Shirtliff ME. Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Am Soc Microbiol 2014;10:419–40. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00092-13

4. Clayton JJ, Baig W, Reynolds GW, Sandoe JA. Endocarditis caused by Propionibacterium species: a report of three cases and a review of clinical features and diagnostic difficulties. J Med Microbiol 2006;55:981–7. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.46613-0

5. Sohail MR, Gray AL, Baddour LM, Tleyjeh IM, Virk A. Infective endocarditis due to Propionibacterium species. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:387–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02703.x

6. Kanafani Z. Invasive Cutibacterium (formerly Propionibacterium) infections. Uptodate.com 2020. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/invasive-cutibacterium-formerly-propionibacterium-infections [accessed 18 June 2020].

7. Lindell F, Söderquist B, Sundman K, Olaison L, Källman J. Prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Propionibacterium species: a national registry-based study of 51 Swedish cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;37:765–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3172-8

8. Verkaik NJ, Schurink CAM, Melles DC. Letter to the editor, Antibiotic treatment of Propionibacterium acnes endocarditis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24:209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2017.07.024

9. Banzon JM, Rehm SJ, Gordon SM, Hussain ST, Pettersson GB, Shrestha NK. Propionibacterium acnes endocarditis: a case series. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23:396–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.026

10. Yamamoto R, Miyagawa S, Hagiya H et al. Silent native-valve endocarditis caused by Propionibacterium acnes. Japanese Intern Med 2018;57:2417–20. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.9833-17

11. Braun DL, Hasse BK, Stricker J, Fehr JS. Prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Propionibacterium species successfully treated with coadministered rifampin: report of two cases. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2012007204. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007204

12. Corvec S. Clinical and biological features of Cutibacterium (formerly Propionibacterium) avidum, an underrecognized microorganism. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018;31:1–42. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00064-17

13. Uslan DZ, Sohail MR, St Sauver JL et al. Permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator infection: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:669–75. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.7.669