A post-meeting report from the Bayer 2022 Cardiovascular Exchange Summit ‘Inspire change’

Faculty

| Faculty member | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Professor Ahmet Fuat | PCCS Council Member and GPSI Cardiology, County Durham |

| Professor Chris Gale | Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine and Honorary Consultant Cardiologist, University of Leeds |

| Dr Guy Lloyd | Consultant Cardiologist, Barts Heart Centre and Honorary Secretary, BCS |

| Helen Williams | National Specialty Adviser for CVD Prevention, NHSE & NHSI and Consultant Pharmacist for CVD, SE London CCG and UCL Partners |

| Dr Jim Moore | President of the PCCS and GPSI Cardiology, Gloucestershire |

| Trudie Lobban, MBE | Founder of the AF Association |

| Professor Vijay Kunadian | Professor of Interventional Cardiology, Newcastle University and Honorary Consultant Interventional Cardiologist, Freeman Hospital Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust |

| Dr Wajid Hussain | Consultant Cardiologist & Chief Clinical Information Officer, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals |

| Key: AF= atrial fibrillation; BCS = British Cardiovascular Society; CCG = clinical commissioning group; CVD = cardiovascular disease; GPSI = general practitioner with a special interest; NHS = National Health Service; NHSE & NHSI = National Health Service England and National Health Service Improvement; PCCS = Primary Care Cardiovascular Society; SE = south-east; UCL = University College London | |

Abstract

The Bayer Cardiovascular Exchange Summit 2022 was organised in partnership with the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) and the Primary Care Cardiovascular Society (PCCS). This meeting provided a platform for the exchange of clinical and patient expertise and innovation across the field of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It aimed to highlight opportunities to improve CVD management and to address the excess post-pandemic cardiovascular (CV) mortality. The meeting was centralised around three core areas: collaborative working between the National Health Service (NHS), pharmaceutical industry and patient advocates; synergistic working across primary and secondary care; and opportunities for healthcare digitalisation.

Joint working between the NHS and the pharmaceutical industry can help to bridge gaps in skills, contribute to quality improvement (QI) and provide learnings for future projects. Good clinical governance is key and collaborations between the NHS and multiple industry partners may overcome the risk of perceived bias. Patients should be central to all NHS-industry projects and all projects should include a patient voice by including the right patient at all times. Their perspective and views should be considered when creating CVD policies or during clinical research to allow transformation of CVD diagnostic and management services. Enriching partnerships between health care professionals (HCPs) and a diverse group of patient advocates is vital to improve patient management. Patient advocates can raise awareness of CVD and engage more patients to better understand their condition.

Improved communication, awareness of expectations and collaborative working between primary and secondary care services can facilitate optimum patient care. However, challenges exist at the primary-secondary care interface, such as long waiting lists for referrals and miscommunication. End-to-end pathways for health, social care, voluntary and community services should be mapped across the healthcare system nationally, with importance placed on integrated care via integrated clinical leadership. There is an inverse care pyramid in relation to investment, which is often top-heavy, aimed at secondary and tertiary care. Investing more resources in primary care services for public health promotion may reduce the CVD burden. More effective utilisation of annual CVD reviews, upskilling primary care teams on CVD and provision of expertise across each locality in the form of a CVD lead may optimise CVD management.

Digital healthcare technologies can provide opportunities to identify high-risk CVD patients through the use of artificial intelligence, NHS electronic health records (EHR) and digital diagnostic tools. Currently available data can innovatively be used at scale to develop pathways that allow early detection of CVD such as atrial fibrillation (AF). However, it is important to consider who will be responsible for undertaking the work and funding digital initiatives. Digital innovation can be seen with the advent of patient portals and mobile applications. New digital technologies must be supported by robust evidence, be cost-effective, allow an improvement in safety outcomes and increase productivity. They can be used to support patients with managing their condition by inducing behavioural change and facilitate communication between HCPs and patients in a timely and flexible manner. However, patient consent is essential, and it is important to note that digital tools may not suit every patient; these groups should not be disadvantaged and non-digital options should be readily available for such groups.

The outputs of the Bayer Cardiovascular Exchange Summit 2022 included valuable expertise from stakeholders involved in CVD management, including HCPs working across primary and secondary care and patient representatives. Greater partnerships between the NHS, pharmaceutical industry and patient advocacy groups with better communications across primary and secondary care services and adoption of digital innovations is vital for improving CVD management.

Introduction

The 2022 Bayer Cardiovascular Exchange Summit was run in partnership with the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) and the Primary Care Cardiovascular Society (PCCS) with an aim to encourage scientific dialogue through the exchange of clinical expertise from specialists with an interest in the management of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and healthcare service delivery in the UK.

The meeting objectives were:

- To update delegates on the latest advances in CVD clinical research

- To highlight present and future challenges in CVD management

- To provide a forum to discuss opportunities within CVD management for collaborative working with the pharmaceutical industry and patient advocates and synergistic working between primary and secondary care

- To address unmet clinical needs in CVD care and service delivery

The meeting addressed three key topics:

- Collaborative working between the National Health Service (NHS), pharmaceutical industry and patient advocates

- Synergistic working between primary and secondary care

- Healthcare digitalisation

Each topic was covered by plenary presentations, delivered by clinical expert speakers or a patient group expert representative, followed by workshops, chaired and facilitated by a faculty of clinical experts within cardiovascular (CV) medicine, which involved discussions between the expert faculty and attending delegates.

Both the BCS and PCCS are committed to working in partnership with patients, the pharmaceutical industry and relevant organisations with aligned strategic aims to identify the current challenges in CVD management within the NHS and to identify solutions to address these.

This report summarises the key messages from the meeting.

Collaborative working between the NHS, pharmaceutical industry and patient advocates

Quality improvement involves systematically using tools to continuously improve the quality of care delivered and outcomes for patients. It should be a key consideration when redesigning healthcare services.1

There are five different NHS and pharmaceutical industry models of working (see table 1), providing valuable opportunities for CVD management through collaborative work. Some of these models of working can be complex and so there is a need for a clear, transparent approach to collaboration. Clear objectives of NHS and industry joint working and good clinical governance is needed with a recognition of where priorities differ; the transparency of declarations is key. There should be a clear structure for funding and reimbursement for projects. It is important to include patient organisations and representatives in all NHS/pharmaceutical industry joint working projects to ensure the needs and views of patients are considered. Disseminating learnings from local NHS–industry partnership projects can highlight the successes and limitations of joint working.2

Table 1. Different NHS and pharmaceutical industry models of working

| NHS/pharmaceutical industry models of working | Description |

|---|---|

| Industry-commissioned studies |

|

| Joint working agreements |

|

| Donations and grants |

|

| Competitive grant application schemes |

|

| National commercial partnerships |

|

| Key: NHS = National Health Service; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | |

In routine clinical care, there are often missed opportunities to improve CVD prevention.4 Engaging patients early to ensure they understand the detrimental consequences of atrial fibrillation (AF) is important. Empowering both patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) can help to optimise the AF dialogue between both parties with respect to correct questions asked and information relayed.

Patients must be at the forefront of healthcare and patient–HCP partnerships can be enriched through involvement of patient organisations and patient advocates, which are vital for raising public awareness of CVD and in implementing better diagnosis and care.5 Patient organisations and advocates can communicate lived experiences of everyday realities of care and management. This can emotionally resonate with policymakers and this power should be harnessed by including their expert opinion when creating CVD policies and developing CV health services.5

Examples in practice

View details

Key points: Collaborative working between the NHS, pharmaceutical industry and patient advocates

Considerations around pharmaceutical industry and NHS collaborations

- Engagements between commissioners and pharmaceutical industry should be overseen by careful governance and any partnership should involve an NHS organisation that is a legal entity in its own right, to provide academic rigor

- The preferred way of working is to collaborate with multiple pharmaceutical companies for any specific disease area so as to avoid the risk of perceived bias for a specific drug product

- Regulations for working with different industries (pharmaceutical/device/diagnostics) should be more aligned

- The quality improvement (QI) capability within the NHS is generally limited but industry can support the NHS, particularly where there are skill shortages, such as in project management

- Projects need to have the capacity to be sustained in the longer term to ensure progress is not lost

- A failed project may still be useful as it can provide valuable learnings for future work

Importance of patient organisations and patient advocates

- Patients should be at the heart of everything and consideration should be given to involving patients in all projects, the steering committees of research studies, trial design and practice-changing documents. Involving patients can transform CVD diagnostic and management services. What is good for patients will ultimately also be good for pharmaceutical companies and the NHS

- Inclusion is essential – both clinicians and patients should have equal representation and voices

- Training volunteers to participate in forums is essential and selecting the correct panel of patients for patient engagement is important as the patient voice is often underutilised. Patient associations can support with raising patient awareness and HCPs, NHS and educational bodies and industry should be encouraged to work closely with them. Patient organisations can disseminate knowledge and information as well as identify patients to participate in studies

- It is important for patient organisations to be involved in the selection of patient representatives, and on what criteria, to ensure they provide a broad view and not just their own personal experience. Including patient representatives from diverse backgrounds to represent the local communities is key to addressing health inequalities

- Barriers to successful patient engagement include lack of time and resources, and patients being insufficiently empowered to make effective contributions. Patient organisations can provide an environment where patients are comfortable to contribute

- Multidisciplinary care models are often not available and more needs to be done to improve patient care pathways

Synergistic working between primary and secondary care

According to NHS England, “Good organisation of care across the interface between general practice and secondary care providers is crucial in ensuring that patients receive high-quality care and in making the best use of clinical time and NHS resources in both settings.”6 However, challenges exist at the primary–secondary care interface. Post-COVID-19, secondary care referrals have built up, there are major waiting lists and there have been many did-not-attend appointments. Issues with miscommunication with respect to dissemination of advice to primary care colleagues has impacted upon re-referrals; HCPs may be unsure at which point patient management stops being the responsibility of secondary care services following referral.6,7

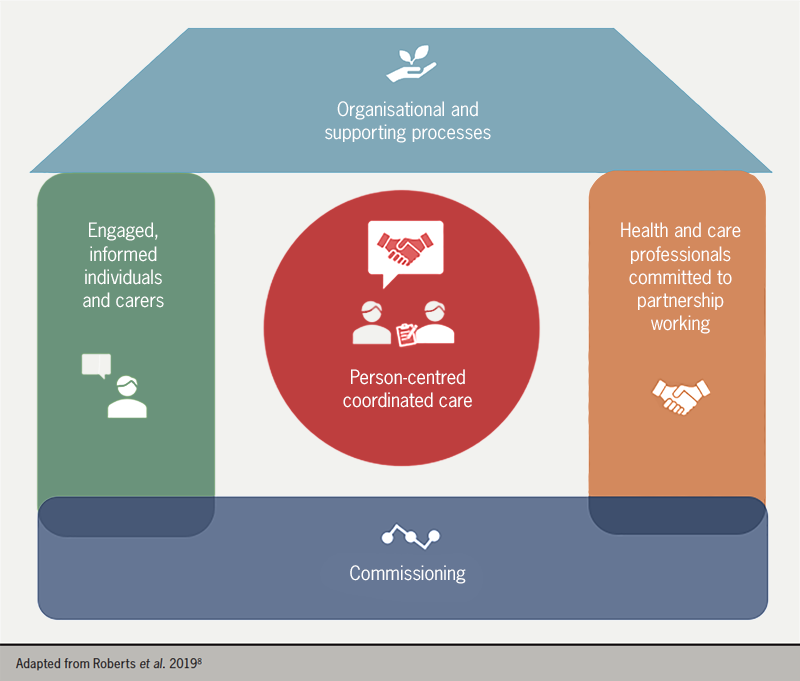

The approach to CVD management should be person-centred and should follow NHS England’s House of Care framework for long-term condition management (figure 1).8

End-to-end pathways for health, social care, voluntary and community services should be mapped across the system with an emphasis on integrated care, combining care provision through general practitioner (GP) practices, primary care networks (PCNs), community pharmacies and community-based and hospital services, as appropriate. Care should be tailored to the individual’s needs and not that of the system.9

Example of a pre-existing pathway for CVD within the NHS includes the CVD prevention pathway with a focus around the AF, blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol (ABC) agenda.10

Integrated clinical leadership is necessary to deliver integrated care. Priorities should be determined by following a population health management approach. System-wide clinical guidance and integrated information technology (IT) systems can help to improve communication and access to population data. Integrated care boards (ICBs) can also provide strategic overview and coordination; however, these are still in their infancy.11

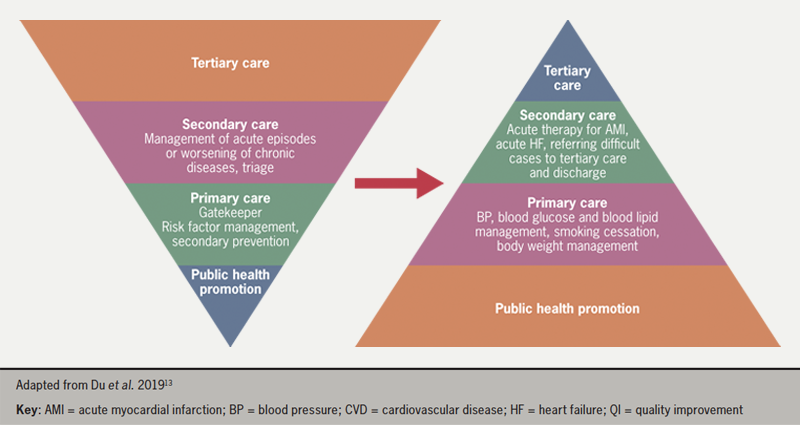

All care should be patient-centred, and patients should be involved at all stages of decision-making regarding care and supported to self-manage their care.12 The provision of CV services can be viewed as an inverted pyramid, with the bulk of management occurring in primary care through public health promotion and primary and secondary prevention of CVD. Fewer patients are then managed by secondary and tertiary care, respectively. However, the pyramid should be flipped when representing levels of funding associated with each level of care (figure 2). Addressing CVD risk factors by investing in primary care services and patient organisations for public health promotion may result in enhanced CV care.13

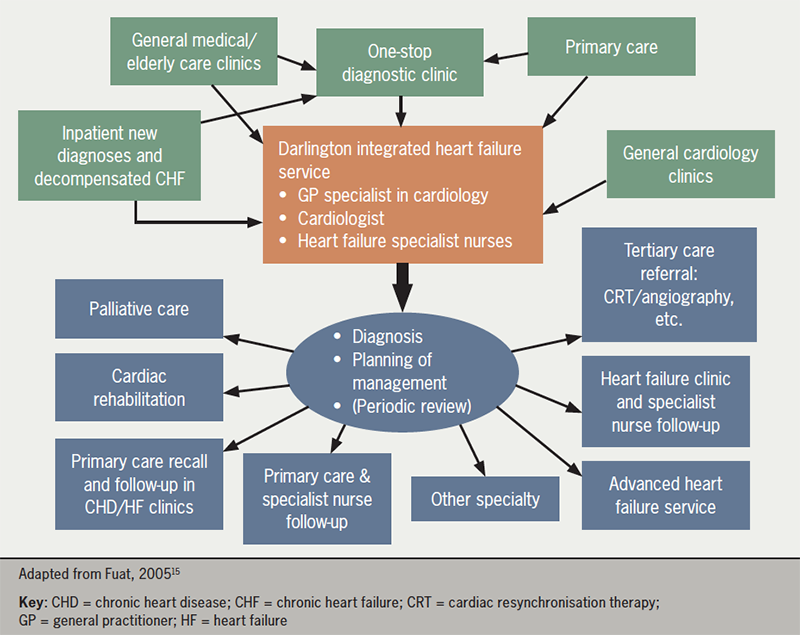

Heart failure (HF) is one example of a CV condition where having clear patient pathways in place across both primary and secondary care offers potential benefits to both patients and healthcare providers.

Examples in practice

View details

Key points: Synergistic working between primary and secondary care

Importance of primary and secondary care relationships

- Better two-way relationships and improved communication between primary and secondary care services is needed to enable GPs to access specialist guidance without having to re-refer patients to secondary care, and to optimise patient management post-discharge with shared ownership of targets and management plans

- Standardised targets for lipid and blood pressure (BP) management can improve patient management post-discharge

- Healthcare professional (HCP) civility is essential to enabling a joined-up service; HCPs need to be kind to one another as well as to their patients, and equally patients need to be kind to HCPs in return

Optimising CVD services

- There is a huge disparity in access to CVD services nationally and locally, likely attributed to the variations in resources, primary and secondary care expertise and HCP level of interest, time and knowledge

- Every PCN should have a CVD lead to ensure expertise in every locality, working closely with secondary care teams to further their expertise, with better interface working

- Taking examples of good practice in one locality and implementing them elsewhere can be valuable

- Better education and upskilling of primary care HCPs on CVD management, including post-discharge care, is important

- HCPs should make the most of the wider healthcare opportunities afforded them during annual checks related to Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators

- Clinical pharmacists can play a vital role in supporting nurses to optimise the management of patients with CVD

Healthcare digitalisation

Optimising identification and management of high-risk CVD patients is essential16,17 and solutions are urgently needed to overcome the rising number of CVD events due to treatment delays, cancellations and NHS backlog following the COVID-19 pandemic. Innovations, such as digital technologies, may provide opportunities to improve health outcomes. Furthermore, identifying patient cases through the use of artificial intelligence (AI), NHS electronic health records (EHR), digital diagnostic tools and digital care hubs may allow medicines personalisation at an industrial scale.18–21

Early AF detection is a key priority of the NHS Long Term Plan,22 and accurately detecting AF, at scale and efficiently using routinely collected data, is needed.

Examples in practice

View details

Checks for new digital technologies

New digital technologies should be backed by evidence and scrutinised to ensure they are cost-effective, increase productivity and improve safety outcomes. They should allow interactions between professionals and ensure that the needs of the patients are at the centre.

Some of the many different areas of digital innovation include patient portals, mobile applications and wearable devices.27 Patient portals can facilitate patient interactions, allowing appointment scheduling, messaging and access to their health information. They can also avoid the need for unnecessary consultations.28 Well-being applications on mobile devices can be used to monitor health markers, such as weight, by connecting to weighing scales and assessing trends over time. Visual representation of test results can prove valuable to patients and their HCPs. Applications can also be useful for targeted education, such as inhaler device counselling. Although there are now an increasing number of mobile applications available, it is essential to ensure that these are reliable, effective and safe.29

Examples in practice

View details

Key points: Healthcare digitalisation

Impact and considerations for patients

- Patients should be empowered, provided with greater ownership of their condition and motivated to manage their own health, for example, through:

- The use of digital technologies, such as to induce behaviour change to optimise medication adherence through reminders. However, whilst the regulatory framework for the approval of medical devices by health authorities is evolving, it may sometimes be difficult to identify these technologies which are indeed Medical Devices Regulation-approved

- Embedding patient information links into primary care clinical systems for HCPs to send accredited health information from patient organisations to patients directly or signposting patients to useful resources and patient organisations for further support

- Giving patients ownership and access to both their primary and secondary care components of their medical records

- Allowing patients access to health information in bite-sized pieces at different times to ensure they stay regularly informed

- Educating patients on treatment pathways and targets to ensure adherence to treatment

- Patients have holistic needs and require not only clinical but also emotional and psychological support, which can be offered through online patient health communities such as the Stroke Association’s “My Stroke Guide”33 and the social media platform, HealthUnlocked34

- Digital systems can allow vast amounts of data, such as BP measurements, to be obtained quickly in a way that patterns can be identified and can encourage patient self-management of care

- Not all patients have a registered GP and digital solutions would not benefit every patient as not everyone is digitally literate or uses smart phones. Some patients may also mistrust technology, which can limit digitalised healthcare

Impact and considerations for HCPs

- All HCPs would benefit from increased digitalisation across both primary and secondary care services

- Treatment decisions and recommendations can differ between digital systems and the HCPs own clinical viewpoint, so it is important that patients are not left confused regarding condition management

- There is a lot of fragmented health information available for patients and HCPs would benefit from understanding where all these resources are in order to support patients

- Digital innovations can allow for more flexibility, and more timely and frequent patient consultations and arrangement of face-to-face appointments where needed, permitting HCPs to spend more time with select patients where required and reducing the need for travel

Regulatory considerations for digitalised healthcare

- Clarity is needed on who has access to personal patient data and how it is used

- Communication between the GP practice and the patient will be key and there must be consent, i.e. patients should be able to opt-out of digital services

- The right pathways and rules must be in place within healthcare for clinicians, managers and patients for the use of digital systems with appropriate management of patient expectations

Organisational considerations for digitalised healthcare

- Appropriate implementation of digital health management could impose an additional burden across primary care and requires investment into the resources and workforce needed to manage care

- Responsibility for the successful delivery of services should be assigned in the event that digital population health management is established

- There is an opportunity to innovatively use currently available data at scale to develop pathways to remove the burden of care and to aid earlier detection of CVD

- An approach to digital innovation within healthcare is to start by focussing on smaller areas and seeking support from peers who may have experience of undertaking similar projects

- The power of social media can be harnessed to engage patients and improve health outcomes

- Socio-economic differences mean digital enablement is varied and there will always be hard-to-reach populations

- Digital innovations should address health inequalities and promote equitable access to healthcare services

- Digital technologies cannot completely replace traditional healthcare methods and patients must be advised that if they are feeling unwell, they should seek a face-to-face appointment by an appropriate HCP in a timely manner

- Time saved through the use of digital technologies should be used to improve services

Concluding comments

The faculty members and delegates present represented stakeholders involved in CVD management, including HCPs working across both primary and secondary care, nurses, pharmacists, patient advocacy organisations and patient representatives, providing a good balance of experience, expertise and opinion. There was a clear consensus that CVD management within the NHS can be improved and streamlined through stronger partnerships between the NHS, pharmaceutical industry and patient advocacy groups; stronger communication between primary and secondary care; and the adoption of digital innovations aimed at benefitting patients and healthcare providers within the NHS. Most importantly, the patient should be at the heart of everything we do.

Key take-home messages

Collaborative working between the NHS, pharmaceutical industry, patient advocacy groups and patient representatives:

- Consider engaging more than one industry partner in contracts when partnering with the pharmaceutical industry

- Governance is critical when working with industry

- There is no such thing as failure – even ‘failed’ projects still have learning potential

- Patients should be central to all NHS-industry projects and can provide unexpected insights:

- All projects should have a patient voice, which should equal to all other voices

- Patient selection is key – involve the right patient and patient organisation throughout and in the right group

- Patient power has the ability to bring about change

Synergistic working between primary and secondary care:

- Better understanding, communication and appreciation for each other is needed between different professional roles:

- Primary care needs to be aware of what is expected from secondary care, and vice versa

- There is an inverse care pyramid when it comes to investment:

- Investment is often top-heavy, aimed at secondary and tertiary care

- Better funding is needed for primary care where most CVD prevention is managed

- There is a need for clear pathways with consistent service provision across the country and more effective use of annual reviews

Healthcare digitalisation:

- Patient consent is critical when considering the use of digital healthcare technologies

- There is a need to consider who might be excluded (e.g. those who are less familiar with digital technology or those who don’t want to engage with it) and ensure they are not disadvantaged

- Considerations around who will fund digital initiatives include:

- Who will fund the initiatives?

- Who will do the work?

- How/where will the results be available?

- How will different groups be incentivised?

Acknowledgements

Bayer would like to thank the chairs, faculty and delegates for their opinions, enthusiasm and engagement throughout the meeting.

Funding

The creation of this report was funded by Bayer plc.

Conflicts of interest

The following faculty members received an honorarium for participating at the meeting: AF, GF, CG, WH, VK, TL, JM, HW. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

References

1. Alderwick H, Charles A, Jones B, Warburton W. The King’s Fund: Making the case for quality improvement. Published 11 October 2017. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/making-case-quality-improvement#:~:text=The%20term%20%27quality%20improvement%27%20refers,Healthcare%20Improvement%27s%20Model%20for%20Improvement (last accessed 09 August 2023)

2. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI). Working together: A guide for the NHS, healthcare organisations and pharmaceutical companies. Amended 13 June 2022. https://www.abpi.org.uk/publications/working-together-a-guide-for-the-nhs-healthcare-organisations-and-pharmaceutical-companies/ (last accessed 09 August 2023).

3. The Prescription Medicines Code of Practice Authority (PMCPA). Code of practice for the pharmaceutical industry 2021: clause 23 donations and grants. 2021. https://www.pmcpa.org.uk/the-code/2021-interactive-abpi-code-of-practice/clause-23-donations-and-grants/ (last accessed 09 August 2023).

4. Sheppard JP, Fletcher K, McManus RJ, Mant J. Missed opportunities in prevention of cardiovascular disease in primary care: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e38–46. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X676447

5. Arrhythmia Alliance. Atrial fibrillation. 2022. https://heartrhythmalliance.org/aa/uk/atrial-fibrillation-af (last accessed 09 August 2023).

6. NHS England. The interface between primary and secondary care: key messages for NHS clinicians and managers. First published July 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/interface-between-primary-secondary-care.pdf (last accessed 09 August 2023).

7. GOV.UK. Direct and indirect health impacts of COVID-19 in England: emerging omicron impacts. Published 04 August 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/direct-and-indirect-health-impacts-of-covid-19-in-england-emerging-omicron-impacts/direct-and-indirect-health-impacts-of-covid-19-in-england-emerging-omicron-impacts (last accessed 09 August 2023).

8. Roberts S, Eaton S, Finch T, et al. The Year of Care approach: developing a model and delivery programme for care and support planning in long term conditions within general practice. BMC Family Practice 2019;20:153. https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-019-1042-4

9. Ali SN, Alicea S, Avery L, Beba H, Kanumilli N, Milne N. Best practice in the delivery of diabetes care in the primary care network. Published April 2021. https://diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/Diabetes-in-the-Primary-Care-Network-Structure-April-2021.pdf (last accessed 09 August 2023).

10. NHS. Future NHS Collaboration Platform: National Cardiac Improvement. https://www.england.nhs.uk/futurenhs-platform/ (last accessed 09 August 2023).

11. Department of Health & Social Care. Health and Care Bill: Integrated Care Boards and local health and care systems. Last updated 20 March 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-and-care-bill-factsheets/health-and-care-bill-integrated-care-boards-and-local-health-and-care-systems (last accessed 09 August 2023).

12. Kuipers SJ, Nieboer AP, Cramm JM. Easier said than done: healthcare professionals’ barriers to the provision of patient-centered primary care to patients with multimorbidity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:6057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116057

13. Du X, Patel A, Anderson CS, Dong J, Ma C. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China and opportunities for improvement. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:3135–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.036

14. Public Health England. State of the North East 2019: Cardiovascular disease prevention. Published October 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/837332/State_of_the_North_East_2019_CVD_prevention.pdf (last accessed 09 August 2023).

15. Fuat A. Bridging the treatment gap: the primary care perspective. Heart 2005;91(suppl 2):ii35–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.062109

16. NHS Benchmarking Network. CVDPREVENT. 2023. https://www.nhsbenchmarking.nhs.uk/cvdpreventlanding (last accessed 09 August 2023).

17. British Heart Foundation. Heart Matters: more people are waiting for heart care because of COVID-19. 2021. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/news/covid-heart-delays (last accessed 10 August 2023).

18. NHS Digital. Summary Care Records (SCR). Updated 05 July 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/services/summary-care-records-scr (last accessed 10 August 2023).

19. NHSX. Artificial Intelligence: How to get it right. October 2019. https://transform.england.nhs.uk/media/documents/NHSX_AI_report.pdf (last accessed 10 August 2023).

20. Department of Health & Social Care. A plan for digital health and social care. 29 June 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care/a-plan-for-digital-health-and-social-care (last accessed 10 August 2023).

21. Airedale Digital Care Hub. About Us. 2023. https://www.airedaledigitalcare.nhs.uk/about-us/ (last accessed 10 August 2023).

22. NHS. NHS Long Term Plan. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (last accessed 10 August 2023).

23. Nadarajah R, Wu J, Frangi AF, Hogg D, Cowan C, Gale C. Predicting patient-level new-onset atrial fibrillation from population-based nationwide electronic health records: protocol of FIND-AF for developing a precision medicine prediction model using artificial intelligence. BMJ Open 2021;11:e052887. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052887

24. Nadarajah R, Wu J, Hogg D, et al. Prediction of short-term atrial fibrillation risk using primary care electronic health records. Heart 2023;109:1072–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2022-322076

25. Nadarajah R, Alsaeed E, Hurdus B, et al. Prediction of incident atrial fibrillation in community-based electronic health records: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Heart 2021;108:1020–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2021-320036

26. NHS. Royal Brompton & Harefield hospitals. Capture AF. 2023. Published online 25 April 2023. https://www.rbht.nhs.uk/our-services/heart/heart-rhythm/capture-af (last accessed 10 August 2023).

27. Sheikh A, Anderson M, Albala S, et al. Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. Lancet Digit Health 2021;3:e383–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00005-4

28. Carini E, Villani L, Pezzullo AM, et al. The impact of digital patient portals on health outcomes, system efficiency, and patient attitudes: updated systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e26189. https://doi.org/10.2196/26189

29. Akbar S, Coiera, E, Magrabi F. Safety concerns with consumer-facing mobile health applications and their consequences: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:330–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz175

30. NHS England – Transformation Directorate. Virtual outpatient clinic for remote follow-ups post-acute myocardial infarction. https://transform.england.nhs.uk/key-tools-and-info/digital-playbooks/cardiology-digital-playbook/virtual-outpatient-clinic-for-remote-follow-ups-post-acute-myocardial-infarction/ (last accessed 10 August 2023)

31. Ortus iHealth – Revolutionising Acute Myocardial Infarct (AMI) at Bart’s Heart Centre. https://ortus-ihealth.com/portfolio-item/revolutionising-acute-myocardial-infarct-ami-at-barts-heart-centre/ (last accessed 10 August 2023)

32. Digital Health London. Ortus i-Health. Last updated 29 April 2022. https://digitalhealth.london/innovation-directory/profile/ortus-i-health (last accessed 10 August 2023)

33. Stroke Association. My Stroke Guide: Welcome. https://mystrokeguide.com/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIsMyW7bjY-wIVGuztCh3ovgmfEAAYASAAEgL1p_D_BwE (last accessed 10 August 2023)

34. HealthUnlocked. https://healthunlocked.com/ (last accessed 10 August 2023)