Heart failure (HF) is a significant problem in the UK with variation in services across the country. Here we describe the findings from a cross-sectional survey of HF services in the UK performed between September 2021 and February 2022.

Seventy-nine responses describing hospital-based HF services from all devolved countries were received. The clinical lead in 82% of hospitals was a cardiologist with specialist interest in HF. Just over half of HF hospital services had a one-stop diagnostic clinic with a median of two clinics per week. A two-week pathway and six-week pathway were present in 78.5% and 75%, respectively. Only 4% of services met referral waiting time targets 100%, and 15% never met targets. The majority of inpatient HF services reviewed patients with primary (96%) or secondary (89%) admission for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), corresponding percentages for HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) were 68% and 51%, respectively. HF services reported a median of two HF consultant cardiologists, five non-HF consultant cardiologists, one palliative care consultant, two band seven and one band six HF specialist nurses.

In conclusion, considerable variation in hospital-based HF services across the UK exist, which may not meet the needs of patients.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome due to a structural or functional abnormality of the heart that results in elevated intracardiac pressure or inadequate cardiac output at rest or during exercise.1 It affects around 900,000 people in the UK and poses a significant burden on the National Health Service (NHS), accounting for one million bed days per year.2 HF reduces life-expectancy with a one-year survival rate of 75.9% post-diagnosis and a 10-year survival of 24.5%.3 Patients living with HF also suffer from disability and reduced quality of life.4 With an ageing population, greater survival from myocardial infarctions (MI), and increasing prevalence of risk factors, the number of patients with HF continues to grow.

European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations for diagnosing and managing patients with HF.1,5,6 While recommendations for care are clear, variations in HF services across the country may prevent patients receiving timely and appropriate treatment.

The National HF Audit in England and Wales collects data about patients hospitalised with HF,2 but it does not collect data on workforce and specialist services providing outpatient diagnosis and management in hospitals and community services across the UK. In response to this lack of data, the British Society for Heart Failure (BSH) commissioned the development, distribution and analysis of a UK-wide survey of HF specialist services, spanning community, secondary and tertiary care. This report describes the findings from hospital-based HF specialist services. The results of the community services survey are published separately.

Materials and method

This project was overseen by the Chair of the BSH Educational Committee and was supported by the board of the BSH. Ethical approval and informed consent was not required as it was conducted as a national service evaluation within the clinical audit framework.

A cross-sectional survey of all HF services in the UK was conducted from September 2021 to February 2022. The objective was to assess the available workforce and services provided for HF across the country.

Survey development, sampling and data collection

An online survey was developed by 30 HF clinicians who were contacted and interviewed, including representation from the BSH board, Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) team, the National Heart Failure Audit and each of the devolved nations. The survey was developed via Survey Monkey and questions were agreed and tested with feedback from test sites. Two surveys were developed, one on hospital services for HF (appendix 1, available online), and the other on community services.

This manuscript presents the hospital services. The questionnaire was distributed electronically to service leads via NHS England, Scottish Heart Failure Hub and Nurse Forum, and information provided by the Welsh Heart Failure Nurse Forum and Northern Ireland Clinicians. Discussions were held with key HF experts from each of the UK nations to establish contact details for HF service leads in those countries:

- England – NHS England who sent survey directly to each of their 15 cardiac network leads

- Northern Ireland – BSH board member provided contact details of the HF leads for the five Health and Social Care Trusts

- Scotland – Scottish HF Hub lead and Chair of HF Nurse Forum who also sent out the survey directly to their members

- Wales – Chair of Welsh HF Nurse Forum and Deputy Chair of BSH Nurse Forum who provided contact details for HF specialists from the seven Health Care Boards

- BSH – an email was sent to all members of the BSH with a link to the survey asking for it to be filled in by any service leads, or sent to known service leads if not members of BSH.

The survey was carried out between September 2021 and February 2022. The response rate for England and Scotland is unclear; unfortunately, we do not know the number of services who received the survey where they were sent via third parties. We do know that one of the 14 English cardiac networks declined to send the survey to their members, citing duplication as the reason. Response from Wales was 57% and Northern Ireland 60%.

Appendix 1. BSH Mapping Project – Acute/Hospital Survey Questionnaire. * Answer required.

|

* 1. Please can you provide your contact information Name Email Address * 2. About Your Hospital Service Name of Hospital Name of Clinical Lead * 3. Is the clinical lead A cardiologist with subspecialty training in HF A general physician with subspecialty training A GPSI (GP with specialist interest in HF) A HF nurse consultant A HF AHP consultant A HF specialist nurse/ANP Other (please specify) * 4. What is the organisation type? Primary care Secondary care – teaching hospital Secondary care – District General Hospital Tertiary care Health Board 5. How would you describe your locality? Urban (city/town) Rural (sparsely populated and relatively isolated) Mixed Other (please specify) 6. What is the number of patients served by the hospital? 7. Is the population ethnically diverse? (% populations). Please tick one box 0–5% 5–10% 10–20% 20+% * 8. Workforce This question refers to the number of staff in each group that regularly care for adults diagnosed with heart failure. (Please specify number in whole time equivalents) Medical – Consultant Cardiologists with HF training Medical – Consultant Cardiologists with other specialty training Medical – Consultant physician with HF training Medical – GPSI Medical – Specialist palliative care consultant Nursing – Lead HF Nurse/AHP 8a Nursing – HF specialist nurse/ANP band 8b Nursing – Consultant nurse band 8c Nursing – HFSN/ANP band 7 Nursing – HFSN band 6 Nursing – HFN band 5 Nursing – Associate Practitioner band 4 Nursing – HCA band 3 Nursing – HCA band 2 AHPs – Consultant pharmacist AHPs – Specialist pharmacist AHPs – Cardiac physiologists AHPs – Physiotherapist AHPs – Dietitian AHPs – Counsellor AHPs – Psychologist AHPs – OT Admin and Clerical – Designated data clerk (audits) Admin and Clerical – Secretarial and admin support * 9. Patient pathways and services – Diagnostics Does the service provide one-stop diagnostic clinics? Yes No 10. If you answered yes to Q9 please note the number provided per week 11. If you answered yes to Q9, what value indicators are used for natriuretic peptides? * 12. Do you have a 2-week pathway for high risk patients? Yes No * 13. Do you have a 6-week pathway for routine patients? Yes No * 14. Do you have a different pathway? Yes No If Yes – please specify * 15. Are referral waiting targets met? Yes – all of the time Up to 80% Up to 50% Up to 25% Not at all * 16. Which HCPs see the patient? Consultant cardiologist Consultant physician Registrar Cardiac physiologist Specialist nurse/ANP AHP If AHP – please specify * 17. Inpatient care Do all patients referred to the HF service have their diagnosis confirmed by echo/MRI? Yes No If no – please explain why not * 18. Do you have a dedicated inpatient HF team? Yes No * 19. Are all referred patients seen by a HF consultant? Yes No * 20. Are all referred patients seen by a HF specialist nurse/ANP? Yes No * 21. Are all referred patients seen by a pharmacist? Yes No * 22. How frequently are patients seen by team? Daily Once Twice Weekly Other (please specify) * 23. What hours are HF team available? Core hours Mon–Fri Extended hours Mon–Fri 7 days per week 24 hours per day * 24. What patient areas are covered by team? HFrEF – Primary admission HFrEF – Secondary diagnosis HFpEF – Primary admission HFpEF – Secondary to admission All new diagnoses Post acute MI Right heart disease, e.g. corpulmonale * 25. Discharge Are all patients discharged with a management plan? Yes No * 26. Who receives management plan? (tick all that apply) Patient Carer GP Community Team * 27. What written information do patients receive? Trust produced materials BHF Pumping Marvellous Cardiomyopathy UK Other (please specify) * 28. Do patients receive digital/online information? Yes No 29. If you answered Yes to Q28 – is this one of the following: An online tool A digital app Please provide the names of the tool and/or app * 30. Is a plan in place for follow-up 2 weeks after discharge from hospital following a HF admission? Yes No 31. If you answered yes to Q30 who provides the follow-up? Hospital Community Both * 32. Are all HF admissions eligible for 2-week follow-up? Yes No 33. If you answered no to Q32, who does NOT receive 2-week follow-up? * 34. Is the 2-week follow-up target met? Yes No * 35. Are follow-up appointments: F2F Telephone Video A Mixture * 36. Do you have dedicated HF beds? Yes No 37. If you answered yes to Q36, how many? * 38. Do you provide daycase diuretic therapy? Yes No * 39. Do you provide daycase IV iron? Yes No 40. Can discharged patients contact the hospital team? Yes No * 41. Are patient initiated follow-up appointments available? Yes No * 42. Can your patients be managed on a virtual ward? If you answer no to Q42 please move on to Q48 Yes No 43. If you answered yes to Q42, is this HF specific? Yes No 44. If you answered yes to Q42, what HF training do staff receive? 45. Is the ward operational 7 days per week? Yes No 46. Can the virtual ward team be contacted out of hours? Yes No 47. What grades of healthcare professionals manage virtual ward patients? * 48. Do you contribute to any national audits? Yes No If yes – please specify * 49. Do you contribute to any local audits? Yes No If yes – please specify 50. Please tell us what criteria/tool you use to evaluate your service Mortality data Length of stay 30 day re-admissions PROMS PREMS Other (please specify) * 51. Are you happy for BSH to share this information with other stakeholders? Yes No |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on Stata 13.0. Descriptive statistics are presented with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage.

Results

Table 1. Description of hospital-based heart failure services

| Variable | Number | % |

| Clinical lead | ||

| Cardiologist with subspecialty in heart failure | 63 | 82.3% |

| General cardiologist or interventional cardiologist | 4 | 5.1% |

| General physician with subspecialty training | 1 | 1.3% |

| HF specialist nurse or ANP | 8 | 10.1% |

| To be confirmed | 1 | 1.3% |

| One-stop clinic | 41 | 51.9% |

| Median clinics per week | 2 (2–4) | n=39 |

| 2-week pathway | 62 | 78.5% |

| 6-week pathway | 39 | 74.7% |

| Other pathway | 20 | 25.3% |

| Referral waiting-time targets met | ||

| All the time | 3 | 3.8% |

| Up to 80% | 31 | 39.2% |

| Up to 50% | 18 | 22.8% |

| Up to 25% | 15 | 19.0% |

| Not at all | 12 | 15.2% |

| Echo or CMR diagnosis | 67 | 84.8% |

| IP HF team | 63 | 79.8% |

| All referrals are seen by | ||

| HF consultant | 9 | 88.6% |

| HF specialist nurse | 62 | 78.5% |

| Pharmacist | 12 | 15.2% |

| Frequency of review of patients referred | ||

| Once | 11 | 13.9% |

| Daily | 17 | 21.5% |

| Twice | 9 | 11.4% |

| Weekly | 6 | 7.6% |

| Other | 36 | 45.6% |

| Hours of HF team | ||

| Core hours Monday to Friday | 76 | 96.2% |

| Extended hours Monday to Friday | 1 | 1.3% |

| 24 hours per day | 1 | 1.3% |

| 7 days per week | 1 | 1.3% |

| Key: ANP = advanced nurse practitioner; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; HF = heart failure; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IP = inpatient | ||

Seventy-nine responses were received from all four UK nations: England (n=65), Northern Ireland (n=3), Scotland (n=7), and Wales (n=4). In England, responses were from Southeast (n=16), Southwest (n=11), Northeast (n=11), Midlands and East England (n=9), Northwest (n=9), and London (n=8). Just under half of hospitals were district general hospital (DGH) services (49%, n=39) and the remaining hospitals were university or university-affiliated hospitals (51%, n=40). The hospitals were in urban, rural and mixed settings; 33%, 9% and 58%, respectively. Hospitals reported the proportion of ethnic minorities in their populations as ≤5% (41% of hospitals), 5–10% (18% of hospitals), 10–20% (18% of hospitals) and >20% in 23% of hospitals. The median population size of each acute trust was 350,000.

Table 1 shows the description of the HF services. The clinical lead in 82% of hospitals surveyed was a cardiologist with specialist interest in HF, a general cardiologist in 5% and in 10% the HF service was led by a HF specialist nurse (HFSN) or advanced nurse practitioner (ANP).

Outpatient referrals

A total of 52% of hospital services had a one-stop diagnostic clinic with a median of two clinics per week. Most services provided a two-week pathway and a six-week pathway, aligning to NICE/SIGN guidelines for suspected HF (78.5% and 75%, respectively). Only 4% of services met recommended referral waiting times, 39% of services met targets for 80% of referrals and 23% of services met targets for 50% of referrals. In 15% of hospitals services referral waiting times were not met at all. Echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were used for diagnosis of HF in 85% of hospital HF services. All referrals were seen by HF consultants in 89% of services, 78.5% had referrals seen by HFSN, but only 15% of services had a pharmacist seeing all referrals. An ambulatory service providing day-case diuretic and intravenous iron was delivered in 52% and 85% of services, respectively.

Inpatient care

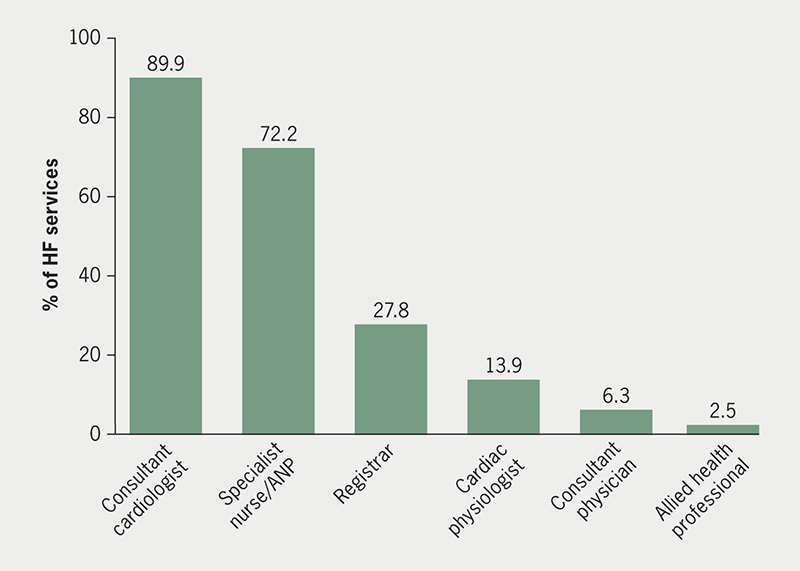

Figure 1 shows the healthcare professionals who conduct inpatient HF reviews. In 90% of services patients were seen by a consultant cardiologist. This was followed by 72% of hospital services having HFSN or ANP review patients. In over 28% registrars reviewed patients. Cardiac physiologists (14%), consultant physicians (6%) and allied health professionals (2.5%) also reviewed patients in a minority of practices. Dedicated HF beds were available in 8% of services. Most services were only available during core working hours Monday to Friday (96%).

Most services reviewed patients who had primary (96%) or secondary (89%) admission for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Only 68% and 51% of services reviewed patients with primary and secondary admissions for HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). In nearly two-thirds of services (65%), patients with any new diagnoses of HF were reviewed, 54% reviewed patients after acute MI, and 47% reviewed patients with right HF.

| Key: ANP = advanced nurse practitioner; HF = heart failure |

In relation to support and information provided for discharged HF patients, most inpatient teams sent discharge plans to patients (91%) and GPs (94%). Information from the British Heart Foundation was the most common information provided to patients (78.5%). Online information was provided to patients by 10% of HF services, an online tool by 6% of patient services and a digital application was available for patients in 8% of services. Many services provided two-week post-discharge follow-up (91%). Follow-up was often split between community (23%) and hospital (21.5%), and follow-up in both for 49% of services. Only half of services accept all HF phenotypes for follow-up (49%). The two-week target was met in 35% of services, either face-to-face or telephone (58%). Nearly all services allowed for discharged patients to access the services (94%), and many had policies for patient-initiated follow-up (75%). A virtual ward was present in 19% and seven-day ward input and out-of-hours input was present in only 16.5% and 11% of HF services, respectively. National audit and local audit participation was 89% and 43.0%, respectively, less than 60% collected data on mortality and 30-day readmissions, and only 10% collected patient-reported outcomes.

Hospital HF workforce and outpatient care

Services reported medians of two cardiology consultants with training in HF, five non-HF cardiology consultants, one palliative care consultant, two Band 7 HFSN and one Band 6 HFSN. The median number of data clerks and administrative support were 0.4 and 0.8, respectively.

A small number of services (23%) had general physicians with specialist interest in HF and 36% had input from one or more GPs with specialist interest in HF. The proportion of services with one or more Band 8a, 8b, and 8c nurses was 57%, 13% and 4%, respectively. Consultant and specialist pharmacists were present in 7% and 41% of services, respectively. One out of 39 hospitals reported that they had a dietitian in the HF services, three out of 40 reported a counsellor and five out of 40 had input from a psychologist.

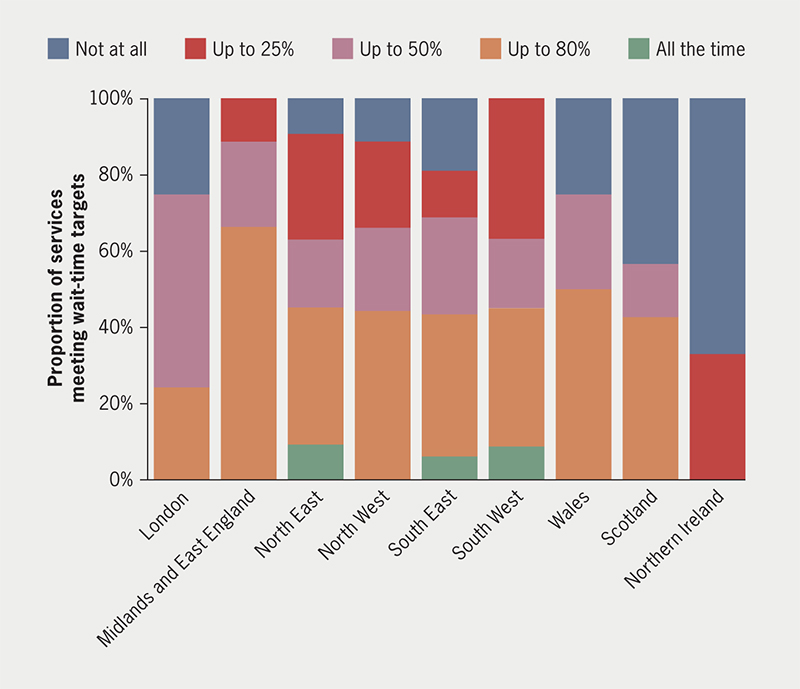

There is variation across geographic regions and devolved nations for meeting the outpatient referral waiting time recommended by NICE (figure 2). NICE waiting time targets were met in less than 10% of referrals in Northeast, Southeast and Southwest England hospitals.

Discussion

This survey has several key findings. HF services in hospitals are primarily led by HF cardiologists, however, approximately 10% of services had no consultant oversight. One-stop clinic models are utilised by half of services surveyed and three-quarters of outpatient services are modelled on NICE guidelines with two-week and six-week pathways.5,6 Fewer than one in 20 services meet 100% of referral waiting time targets. A median number of only two clinics weekly likely contributes to long waiting times for referred patients and the high proportion of patients diagnosed during acute hospitalisation.7 Limited clinics imply that the workload is too high for the availability of clinicians.

Most services review patients with HFrEF, while fewer review patients with HFpEF. Given the increasing numbers of patients with HFpEF and evidence of benefit in pharmacological treatment,8 better services for these patients are needed. Services that may prevent hospitalisation, such as day-case diuretic therapy, was delivered by half of services, and intravenous iron by a majority of services. However, HF virtual wards9 were infrequent.

Communication across all sectors of the healthcare system is essential for continuity of care, but the survey revealed that the community team was only informed of the hospital management plan about two-thirds of the time. The COVID-19 pandemic increased the use of telephone-based clinical reviews in HF;10 25% of services had appointments by telephone, and 58% had a mix of face-to-face and telephone consultations.

HF-specific multi-disciplinary teams are advocated, comprising cardiologists, surgeons, advanced practice providers, clinical pharmacists, specialist nurses, dietitians, physiotherapists, social workers, immunologists, and palliative care clinicians.11 Pharmacists, physiotherapists, dietitians, counsellors, psychologists and occupational therapists were not present in most HF services. The lack of dietitians in HF services was reported in a survey of 10 major US HF centres, with patient teaching on sodium and fluid the responsibility of nurses, and nutritional educational materials not specific to HF leading to confusion among patients.12 Psychological interventions and counselling (given high rates of depression and anxiety in patients with HF) and occupational therapy can improve self-care and decrease hospitalisations.13–15 Physiotherapists have an important role for HF patients with regards to education and exercise prescription.16

While there is no ideal HF service model that can be applied to all services across the country, services require resources to meet population needs, targets for diagnosis and treatment, and data collection on patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness. Population demand will differ based on demographic factors such as age and ethnicity, and levels of deprivation. Socioeconomically deprived patients are 44% more likely to develop HF than affluent patients,17 and ethnic minorities have the highest incidence, prevalence and hospitalisation rates from HF.18 Specialist input is needed to ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment guided by evidence-based guidelines.

This survey has several limitations. The current evaluation had responses from only 79 clinical leads, and inclusion in the survey was voluntary. This survey is descriptive and did not assess population density, demographics and HF prevalence in hospital catchment areas. The survey also did not consider non-HF services in hospitals that provide or impact care for patients with HF, such as emergency departments, geriatrics, general cardiology and other medical specialties. Other nearby hospitals and specialist services in the community are important for meeting population need for HF services. However, this is the first time a survey like this was conducted for HF services, and a better response to future surveys will enable comparisons over time and across regions. The survey did not include patient outcomes or cost data. HF accounts for one million inpatient bed days and 5% of all emergency medical admissions, with an overall cost of £2 billion, so investment in services could result in decreased costs of hospitalisation.19

Nevertheless, the findings of considerable variation across services are important. Services should be encouraged to evaluate their response to demand, ability to provide early diagnosis and guideline-directed therapy, and improve patient outcomes. One approach may be to link the findings of the HF services survey with regional HF statistics and the National Heart Failure Audit.

Conclusion

For the first time, the findings from a national survey of hospital-based HF services describe the workforce, activities and services in the UK, revealing variation across regions. Notably, services struggle to meet waiting time targets for referrals and post-discharge follow-up, hold few weekly clinics and nearly one-third do not review patients with primary admission for HFpEF. Some services to prevent hospitalisation are available: day-case diuretics in 52% and day-case intravenous iron in 85%, but virtual wards in only 19%. Outcome data collection is limited: 30-day readmissions (collected by 58%), mortality (57%), length of stay (49%) and patient-reported outcomes (10%). Eighty-nine percent participate in the National Audit, but only 43% in local audits. These findings indicate the opportunities for improvement in hospital HF services and the need for increased resources.

Key messages

- Heart failure (HF) services in hospitals are primarily led by HF consultants, but about 10% have no consultant oversight

- Fewer than one in 20 services meet 100% of referral waiting time targets and the median number of clinics is only two per week

- Most services review patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) while only one-half to two-thirds review patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)

- Considerable variation in hospital-based HF provision exists, with many services not meeting demand for rapid diagnosis and treatment, indicating opportunities for improvement

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

This project was overseen by the Chair of the British Society for Heart Failure (BSH) Educational Committee and was supported by the board of the BSH. Institutional review board approval and informed consent was not required as it was conducted as a national service evaluation within the clinical audit framework.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the services who took the time to answer the survey and hope that they find the information useful.

Editors’ note

This is the first of two articles on heart failure services in the UK. The second article will be published in Issue 2.

References

1. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

2. National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. National Cardiac Audit Programme. National Heart Failure Audit (NHFA): 2022 summary report. London: Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), 2022. Available from: https://www.nicor.org.uk/national-cardiac-audit-programme/previous-reports/heart-failure-3/2022-4/nhfa-doc-2022-final?layout=default

3. Taylor CJ, Ordonez-Mena JM, Foalfe AK et al. Trends in survival after a diagnosis of heart failure in the United Kingdom 2000–2017: population based cohort study. BMJ 2019;364:l223. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l223

4. Garcia-Olmos L, Batlle M, Aguilar R et al. Disability and quality of life in heart failure patients: a cross-sectional study. Fam Pract 2019;36:693–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz017

5. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of chronic heart failure. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2016. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/management-of-chronic-heart-failure/

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management. London: NICE, 2018. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

7. Bottle A, Kim D, Aylin P, Cowie MR, Majeed A, Hayhoe B. Routes to diagnosis of heart failure: observational study using linked data in England. Heart 2018;104:600–05. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312183

8. Campbell P, Rutten FH, Lee MM, Hawkins NM, Petrie MC. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: everything the clinician needs to know. Lancet 2024;403:1083–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02756-3

9. National Health Service England. Guidance note: virtual ward for people with heart failure. London: NHS England, 2023. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/guidance-note-virtual-ward-care-for-people-with-heart-failure/

10. Sokolski M, Kaluzna-Oleksy M, Tycinska A, Jankowska EA. Telemedicine in heart failure in the COVID-19 and post-pandemic era: what have we learned? Biomedicine 2023;11:2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11082222

11. Sokos G, Kido K, Panjrath G et al. Multidisciplinary care in heart failure services. J Cardiac Fail 2023;29:943–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.02.011

12. Kuehneman T, Saulsbury D, Splett PL. The role of dietician in an outpatient heart failure center. J Am Dietetics Assoc 1997;97:A19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00383-0

13. Jiang Y, Shorey S, Seah B, Chan WX, Tam WWS, Wang W. The effectiveness of psychological interventions on self-care, psychological and health outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Studies 2018;78:16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.08.006

14. Carroll O, Nxumalo K, Bennett A, Pike W. Abstract 245: demonstrating the effectiveness of an outpatient occupational therapy program for individuals with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:A245. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.10.suppl_3.245

15. Dracup K, Baker DW, Dunbar SB et al. Management of heart failure. II. Counseling, education, and lifestyle modifications. JAMA 1994;272:1442–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03520180066037

16. Wu YC, Chen CN. Physical therapy for adults with heart failure. Phys Ther Res 2023;26:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1298/ptr.R0024

17. McAlister FA, Murphy NF, Simpson CR et al. Influence of socioeconomic deprivation on the primary care burden and treatment of patients with a diagnosis of heart failure in general practice in Scotland: population based study. BMJ 2004;328:1110. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38043.414074.EE

18. Lewsey SC, Breathett K. Racial and ethnic disparities in heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol 2021;36:320–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000855

19. Stewart S, Jenkins A, Buchan S, McGuire A, Capewell S, McMurray JJJV. The current cost of heart failure to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:361–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1388-9842(01)00198-2