Heart failure (HF) is a highly prevalent long-term condition, with variation in services and resources across the UK. This report provides findings from a cross-sectional survey of community HF services in the UK between September 2021 and February 2022.

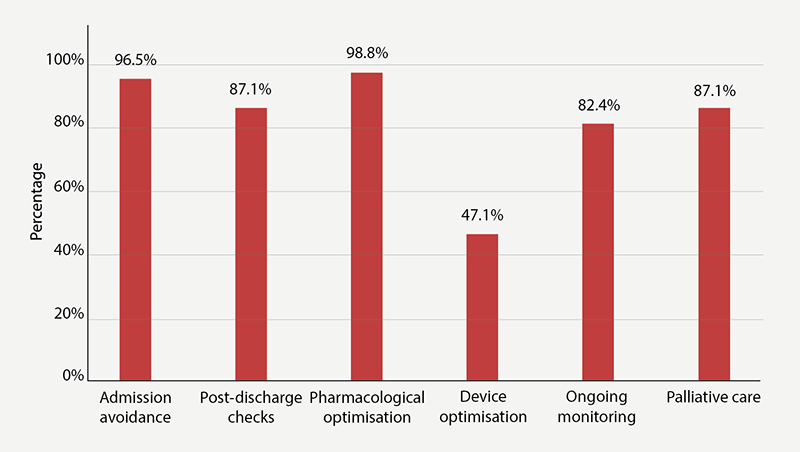

Eighty-five responses describing community HF services were received. Community services were primarily led by a HF specialist nurse (HFSN), with a median of 1.25 cardiology consultants with HF training, and a variety of other nurses and support workers. All services reviewed patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), only 58% reviewed patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Median wait time was 20 days, with substantially longer waits in many areas. All services accepted referrals from multiple sources. Most services provided admission avoidance (96.5%), post-discharge checks (87%), pharmacological optimisation (99%), ongoing monitoring (82%) and palliative care (87%).

In conclusion, UK community-based HF teams provide many services, however, there is significant geographical variation. Studies are needed to determine if they are adequately resourced to meet population needs and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Goals of care for patients with HF are to provide symptom relief, improve prognosis and quality of life, and prevent hospitalisations. Patients with HF are often complex, and multi-disciplinary input is recommended so that patients receive evidence-based treatments and maximise their quality of life.1 In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) encompasses both hospital and community HF services, which work together to keep people living with HF supported and well-managed.2

Community HF teams provide specialist care for patients with HF, and community services are structured around outpatient appointments in healthcare settings or home. During appointments patients can be monitored in terms of their symptoms and clinical signs, investigations reviewed, treatments instigated, and referrals made for specialist care in hospitals. Different models of community HF specialist teams exist, which include cardiology consultants, HF specialist nurses (HFSN), health professionals and, infrequently, GPs with specialist interest (GPwSI) in HF.2

However, little information exists regarding how UK community HF teams are resourced, organised and deliver services for HF patients. In response to this lack of data, the British Society for Heart Failure (BSH) commissioned the development, distribution, and analysis of a UK-wide survey of HF specialist services, spanning community, secondary and tertiary care. In this manuscript, the results of the survey sent to specialist community HF services are presented.

Method

This project was overseen by the Chair of the BSH Educational Committee and was supported by the BSH. Research ethics committee approval and informed consent was not required.

Study design and population

A cross-sectional survey of all HF services in the UK was conducted to assess available healthcare professionals and services in the community and determine how HF resources are similar and different across the country. NHS England and clinical network leads of NHS England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were contacted for their input and participation in an online survey.

Survey development, sampling and data collection

The questions on the online survey were developed by 30 HF clinicians who were contacted and interviewed, including representation from the board of the BSH, each of the devolved nations, and the national HF audit. Two surveys were developed, one focusing on hospital services for HF and the other on community services (appendix 1 available on request). There was a total of 40 questions and, for the purposes of this manuscript, only the community services are presented. The hospital survey is published separately.

Discussions were held with key HF experts from each of the UK nations to establish contact details for HF service leads in those countries.

- England – NHS England who sent the survey directly to each of their 15 cardiac network leads.

- Northern Ireland – a BSH board member provided contact details of the HF leads for the five Health and Social Care Trusts.

- Scotland – the Scottish HF hub lead and chair of HF Nurse Forum who sent out the survey directly to their members.

- Wales – the chair of Welsh HF Nurse Forum and deputy chair of BSH Nurse Forum who provided contact details for HF specialists from the seven healthcare boards.

- BSH – an email was sent to all members of the BSH with a link to the survey asking for it to be filled in by any service lead, or sent to known service leads if not members of BSH.

- The survey was carried out between September 2021 and February 2022. The response rate for England and Scotland is unclear, we do not know the number of services who received the survey from the network/forum leads. We do know that one of the 14 English cardiac networks declined to send the survey to their members. The response rate from Wales and Northern Ireland was 86% and 20%, respectively.

|

Table 1. Description of the location of community heart failure services

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 2. Workforce of heart failure services in the community

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 3. Description of community heart failure services

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on Stata 13.0. Descriptive statistics were presented with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and number and percent for categorical variables. Data are presented in tables and figures.

Results

A total of 85 responses were received, primarily from England (n=69), and a lesser proportion from Northern Ireland (n=1), Scotland (n=8) and Wales (n=6) (table 1). Notably, of the seven health boards in Wales, six took part in the survey. For Scotland, eight of the 15 health boards provided data, and one of five health boards in Northern Ireland submitted data for the community survey. These organisations serviced a variable population including urban (31%), rural (11%) and mixed areas (58%), with a median population of 269,900 based on 39 available responses. Ethnic minorities were reported as comprising 0–5%, 5–10%, 10–20% and >20% of the population for 26%, 26%, 11% and 37% of the services, respectively.

The workforce that made up the community HF teams (85 responses) is described in table 2. The teams had a median of 1.25 cardiology consultants with HF training, 2.6 band 7 nurses, two band 6 nurses, one healthcare assistant band 3, and access to a palliative care consultant. There was also a median of one secretarial or administrative support worker.

The descriptions of the community HF services are shown in table 3. The majority (57%) of services are led by a HFSN, while 39% were led by a cardiologist. All services reviewed patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), two-thirds reviewed patients with heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) and 58% reviewed patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Most operated during the core hours Monday to Friday (94%). More than half of services had a waiting list (56.5%), and 85% of these reported their waiting lists increasing. There was significant variation in waiting times, the shortest was four days and the longest 112 days. Twenty-seven services reported waiting times of 28 days or more.

Figure 1 shows the types of care provided. More than 80% provided admission avoidance (96.5%), post-discharge checks (87%), pharmacological optimisation (99%), ongoing monitoring (82%) and palliative care (87%). Device optimisation was offered by 47% of services. All patients were provided with written information, but online information was provided by only 29% of HF services. An online tool was provided for 13% of patients and a digital application was available for patients in 14% of services. Discharges from the service with management plans were provided by 86%, and in 86% of services patients can self-refer to the community service post-discharge. Self-monitoring tools were available in 78% of services and in 68% the community HF nurse was expected to monitor patients. Patients could be managed on a virtual ward in 20% of services, and in 12% of services the virtual ward was for HF. There was access for day-case diuretics and intravenous iron therapy for 46% and 71% of community services, respectively. Palliative care was available for 98%, and most had access to a palliative care consultant (73%) and hospice (87%). Most services had access to a multi-disciplinary team (89%), which were mostly online meetings (76.5%) rather than face-to-face (35%). Less than half (45%) of community services carry out their own local audits.

Discussion

This survey of community HF services provides a snapshot of the resources and services delivered by HF teams across the UK. Key findings include that services were predominantly led by HFSNs or cardiologists and accept referrals from a wide variety of other healthcare professionals; a majority also accept self-referrals from previous patients. These teams provide several key support services in the management of patients with HF, including admission avoidance, post-discharge checks, pharmacological optimisation, ongoing monitoring, and palliative care. Significant geographical variation was most apparent in relation to waiting times and provision for patients with HFpEF, which continues to lag behind HFrEF. The results suggest online information, digital tools, virtual wards, and day-case diuresis are less available in many community services. Finally, participation in audits and collection of relevant outcome data, including patient-reported outcomes were infrequent. The findings indicate that UK community HF services do provide valuable care for patients living with HF, but many struggle to provide timely and comprehensive support for all HF patients.

HFSNs have a key role in the management of HF.3 Most English integrated care boards (ICBs), and Scottish and Welsh health boards commission community HFSNs to provide follow-up for all HFrEF admissions, review patients who are at risk of hospitalisation, and titrate evidence-based therapies. Although this is not the same in Northern Ireland, where community HF is reportedly organised differently. In the other three nations more than half of community-based services are led by HFSNs. With respect to HFSN numbers, the Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) report into cardiology services recommends three to four HFSNs per 100,000 population.4 We were unable to calculate which areas had the number of HFSNs recommended by GIRFT due to the lack of population data, but hope to address this in subsequent surveys.

We found that more than half the responding services (57%) described waiting lists and 85% reported increasing waiting times. Although median waiting time was 20 days, 27 practices reported waiting times of 28 days or more. The longest waiting times were in the South East and the South West, with each of the devolved nations reporting at least one service with waiting times 28 days or above.

Six services denied having any formal waiting list and had introduced a triage system, with appointment times calculated based on the patient’s clinical stability. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends newly diagnosed HF patients are reviewed by a member of the specialist HF team within 14 days, and within two weeks following an admission to ensure stability and avoid readmissions.5 Triaging could help meet this target, but would likely have the knock-on effect of increasing waiting times for stable patients requiring medicine optimisation. A recent trial6 and European guidelines7 recommend rapid optimisation of four drugs for HFrEF.

Most services accepted referrals directly from previous patients. Patient initiated follow-up (PIFU) is recommended by NHS England,8 to allow patients control over their follow-up care. A key part of empowering patients and delivering personalised care, it is directly aimed at hospital outpatient appointments, with the goal of reducing routine follow-up appointments, but can be applied to a variety of settings and conditions. NHS England provide guidance on how to implement this policy to meet their three minimum quality standards, which include patient education about PIFU, a standard operating procedure, which includes safety nets and a log of all patients given access to a PIFU pathway, and key metrics. While this may provide valuable reassurance to HF patients, PIFU could add to the volume of referrals and put greater pressure on waiting lists. The widespread increase in waiting times for specialist community HF appointments, implies that demand outstrips supply or resources; therefore, it is essential that PIFU is adequately built into the service model and resourced appropriately.

The provision of specialist services for HFpEF still lags behind HFrEF despite recent advances in treatment. Our results showed 100% of services reviewed patients with HFrEF compared with 58% for HFpEF. The role of HFSN in managing patients with HFrEF is well established, as a UK randomised-controlled trial demonstrated decreased readmissions and improved quality of life for patients with HFrEF managed by HFSN compared with usual care.3 HFSN roles in some services have expanded to include HFpEF, as their skills are needed across HF types. Patients with HFpEF have historically been disadvantaged. Recent clinical trials demonstrating the benefit of specific medications have brought greater awareness of HFpEF,9 but clinical pathways and access to services are needed to ensure that patients receive appropriate treatment. To be able to manage HFpEF patients, as well as HFrEF, it is imperative the numbers of HFSN or healthcare professionals are in line with the GIRFT recommendations.

The survey shows that the care provided by community HF services is comprehensive, and has the potential to relieve demands on hospital services and provide alternatives to admission through provision of diuretic therapy, monitoring and palliative care. Most specialist community HF teams comprise HFSN with support from cardiologists and administrative workers, plus access to other members of the multi-disciplinary team, e.g. geriatricians, pharmacists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. However, very few have access to psychologists and counsellors. A majority had access to a HF specialist multi-disciplinary team meeting, thus, facilitating communication and collaboration.

Most services (78%) reported use of self-monitoring systems, such as digital scales and/or blood pressure machines. Few provided digital resources, such as online information, online tools and apps, but several signposted patients to online websites belonging to cardiac charities.

Although 20% reported access to virtual wards, only 12% stated that these were for HF. A systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that post-discharge virtual wards can provide benefits to usual community-based care.10 In its position statement on virtual wards,11 the BSH made several recommendations, including the care plan to be developed by a specialist in HF and implemented by a team with experience in the management of HF.

Participation in audits by community HF teams were infrequent, particularly when compared with hospital services. Clinical audit is an important tool and enables providers to use audit data to understand how care is being provided, how services are being used and whether the service performs when measured against standards and objectives.12 This is often a time-consuming activity and, while most community services do have some basic level of administrative support available, only 19 services had access to designated data support.

This work has several limitations. The current evaluation had responses from 85 clinical leads, and it is estimated that there are considerably more. A key limitation is the lack of population data, which would be helpful to gauge the level of HFSNs required to meet GIRFT recommendations. The survey does not provide information to determine how hospital, primary care and community HF services work together and how efficiently patients are managed. A few services described themselves as integrated, providing specialist care in both hospital and community, but more information about this model of care is needed. Little engagement with primary care was evident in survey responses, but should be explored. An important question on the availability of cardiac rehabilitation programmes for HF patients was omitted from the final survey, this was an oversight and should be included in subsequent surveys. Lastly, the survey does not have outcome or cost data, although HF incurs a significant cost to the NHS, particularly related to hospitalisation. It is arguable that more resources should be invested to expand community care given the increase in demand and waiting times, and to link service provision to outcomes and costs.

Conclusion

This first national survey of HF services in the community clearly shows that HF teams provide valuable services to HF patients. However, the provision of service varies across the country, and may be inadequate to ensure timely assessment post-diagnosis or hospital discharge, care for patients with HFpEF and rapid optimisation of medicines for patients with HFrEF. More studies are needed to determine workload, adequacy of resources, collaboration with other services, cost-effectiveness, and ability to improve patient outcomes.

Key messages

- Community heart failure (HF) services support general practice and hospital services by providing admission avoidance, post-discharge checks, pharmacological optimisation, ongoing monitoring and palliative care

- Referrals are accepted from a wide variety of healthcare professionals. The majority also accept self-referrals from previous patients

- These services are predominantly led by heart failure specialist nurses or a cardiologist

- Significant geographical variation exists in terms of service provision and waiting times

- The provision of services for HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) continues to lag behind HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in many areas

- Online, digital resources and virtual wards may be underutilised or unavailable

- Participation in audit is infrequent

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

This project was overseen by the chair of the BSH Educational Committee and was supported by the board of the BSH. Institutional review board approval and informed consent was not required as it was conducted as a national service evaluation within the clinical audit framework.

Acknowledgement

With thanks to the community services that completed this survey.

Editors’ note

The appendix containing details of the survey is available upon request. See also the results of the hospital survey published in Issue 1 2025 by Kwok et al. https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2025.001

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management. NG106. London: NICE, 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

2. NHS England. What are community health services? Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/community-health-services/what-are-community-health-services/

3. Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JVV et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ 2001;323:715–18. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715

4. Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT). Cardiology. Available at: https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/medical_specialties/cardiology/

5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute heart failure: diagnosis and management. CG187. London: NICE, 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg187

6. Mebazza A, Davison B, Chioncel O et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 2022;400:1938–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02076-1

7. McDonagh T, Metra M, Adamo M et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2023;44:3627–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad613

8. NHS England. Implementing patient initiated follow-up: guidance for local health and care systems. London: NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2022. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/implementing-patient-initiated-follow-up-guidance-for-local-health-and-care-systems/

9. Campbell P, Rutten FH, Lee MM, Hawkins NM, Petrie MC. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: everything the clinician needs to know. Lancet 2024;403:1083–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02756-3

10. Uminski K, Komenda P, Whitlock R et al. Effect of post-discharge virtual wards on improving outcomes in heart failure and non-heart failure populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0196114. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196114

11. British Society for Heart Failure. Position statement on virtual wards. London: BSH, 2023. Available from: https://www.bsh.org.uk/position-statements [accessed 22 April 2024].

12. NHS England. Clinical audit. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/clinaudit