It is widely accepted that end-of-life care for non-cancer conditions has lagged behind that for cancer. The purpose of this survey was to evaluate the confidence of trainees in managing end-of-life issues. An online questionnaire was distributed to all registrar-grade British Junior Cardiac Association members in the UK.

A total of 219 trainees responded. Overall, 73% of trainees feel the care they provide patients with advanced heart failure is poor/adequate. Over 50% of trainees do not feel equipped to discuss advanced-care planning and end-of-life issues. There are 45% who report receiving no training in palliation of advanced heart failure symptoms, while 57% are unhappy with current provision of training. Trainees’ suggestions include more workplace-based supervision with additional regional and national training days, closer links with local hospices, and fellowships for cardiology trainees in palliative care.

Despite being part of the national curriculum for training in cardiology since 2010, trainees’ level of confidence in delivering end-of-life care in advanced heart failure and discussing prognosis is poor. This could be rectified by closer links with palliative care and formal teaching programmes.

Introduction

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome and is the only cardiovascular disease that is increasing in prevalence.1 It has a profound impact on both the patient’s quality of life and functional capacity, as well as causing premature death.2 Traditionally, cancer patients have been the main focus for specialist palliative care services, though it is increasingly well-recognised that chronic heart failure is equivalent to malignant disease,3 with patients experiencing debilitating physical symptoms, as well as psychosocial and spiritual problems. Despite the growing recognition of the palliative care needs of this complex group of patients and their carers, a recent National Heart Failure Audit disappointingly continued to report significant unmet needs, with only 3.1% of those dying with heart failure being referred to palliative care services on their first admission to hospital and 6% on readmission,4 far less than that of oncology patients. The caveat to this is the recognition that coding for referral to palliative care services may not always be accurate, though the number is still likely to be low.

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome and is the only cardiovascular disease that is increasing in prevalence.1 It has a profound impact on both the patient’s quality of life and functional capacity, as well as causing premature death.2 Traditionally, cancer patients have been the main focus for specialist palliative care services, though it is increasingly well-recognised that chronic heart failure is equivalent to malignant disease,3 with patients experiencing debilitating physical symptoms, as well as psychosocial and spiritual problems. Despite the growing recognition of the palliative care needs of this complex group of patients and their carers, a recent National Heart Failure Audit disappointingly continued to report significant unmet needs, with only 3.1% of those dying with heart failure being referred to palliative care services on their first admission to hospital and 6% on readmission,4 far less than that of oncology patients. The caveat to this is the recognition that coding for referral to palliative care services may not always be accurate, though the number is still likely to be low.

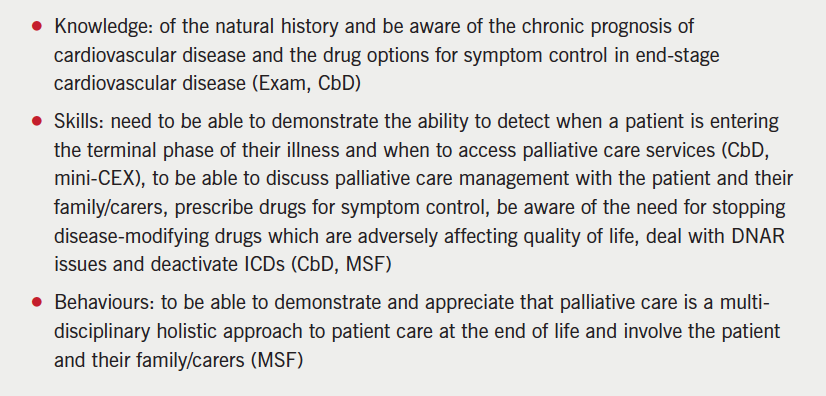

In acknowledgement of this, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published a position statement addressing palliative care in heart failure and proposed that “palliative care should be integrated as part of a team approach to comprehensive heart failure care and should not be reserved for those who are expected to die within days or weeks.”5 The crucial role that palliative care can offer in managing patients with heart failure has also been recognised by the Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board who incorporated end-of-life care into the 2010 cardiology curriculum for trainees, with the aim of ensuring that future cardiologists have the necessary knowledge, skills and behaviour to manage the latter stages of this condition competently (box 1).6 There are no published data of the current levels of competence of cardiology trainees in this area.

We undertook a survey to evaluate the confidence of trainees in this area.

Methods

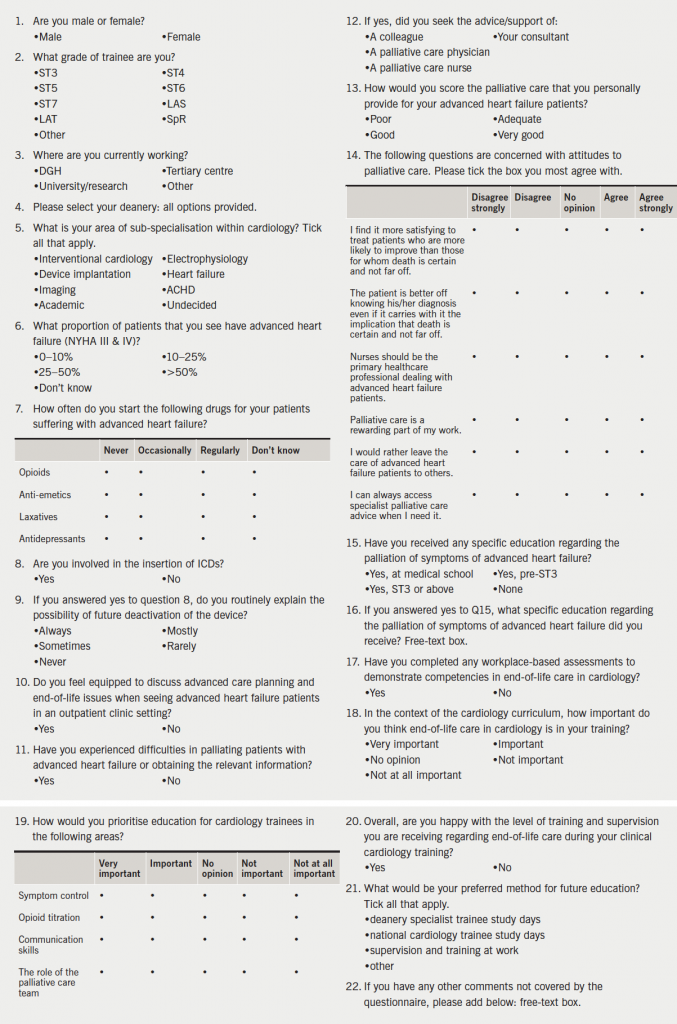

An electronic survey was distributed to registrar-grade members of the British Junior Cardiac Association (BJCA) in the UK in June 2012. Three reminder emails were sent over the following four weeks, after which the survey was closed and analysed. There were 22 questions designed to ascertain what level of palliative care training the respondent had received, how confident they felt in the palliative management of end-stage heart failure patients, how they felt this could be improved upon and how important they felt this area of care was in their training (the full survey questions are available in appendix 1). The survey also explored the attitudes of trainees to end-of-life care in heart failure and the role of palliative medicine. In some questions, trainees were given the opportunity for free-text responses. These responses (27 in total), were subsequently analysed qualitatively by two of the researchers, who independently read and re-read the comments and identified significant statements. These were then grouped into themes, consistent with a thematic analysis method.

Results

Who responded?

Overall, 221 cardiologists in training completed the survey out of 800 who were eligible; a response rate of 28% which is broadly in line with response rates obtained by the BJCA in other studies.7 The responses were received across the range of different level training grades (ST3-7, SpR, LAS/LAT grades) and across different deaneries, with only one deanery not being represented. Responses were received from all cardiology sub-specialities, including interventional cardiology, electrophysiology, cardiac imaging, adult congenital heart disease, heart failure and device implantation, as well as academic trainees.

Clinical training

Trainees were asked about their experience of palliating patients with end-stage heart failure: 73% of trainees’ reported difficulties in palliating patients with end-stage heart failure, but palliative care physicians were consulted in only 56% of cases, with palliative care nurse advice sought in only 46% of cases. Only 26% of respondents felt that the care they provided their end-stage heart failure patients was good/very good. Over half of the trainees (51%) surveyed felt ill-equipped to discuss advanced-care planning and end-of-life issues when seeing advanced heart failure patients in an outpatient setting.

Looking at the trainees’ prescribing habits of opioids, anti-emetics, laxatives and antidepressants in end-stage heart failure, only 30% prescribed opioids, 29% anti-emetics, 24% laxatives and 4% antidepressants, regularly.

Of those trainees involved in the insertion of implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs), only 9.4% always explained the possibility of future deactivation of the device, with a significant proportion of trainees never raising this issue before implantation.

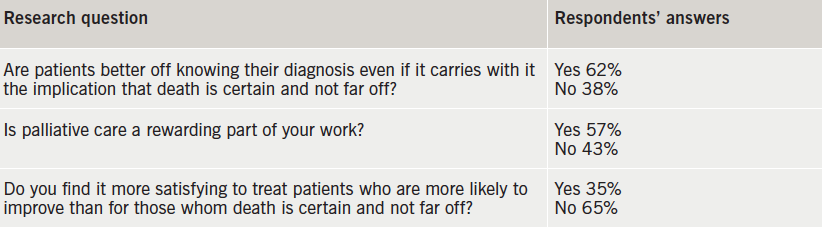

Trainees’ attitudes to palliative care in end-stage heart failure are shown in table 1.

Trainees’ education

There were 42% of trainees who had not received specific education regarding the palliation of symptoms of advanced heart failure. The education that the remainder had received mostly seemed to comprise of isolated lectures as part of general medicine training/SpR teaching or specific courses/study days on the topic. There were only a few examples where practical experience was gained from working directly with the palliative care team. However, 92% of trainees felt that training in end-of-life care in cardiology was important. Key areas for teaching that were identified by trainees to be important were symptom control, opioid titration and communication skills, as well as the role of the palliative care team. Only 22% of trainees had completed a workplace-based assessment, the remainder had not. Overall, 53% of trainees were unhappy with the level of training and supervision they were receiving regarding end-of-life care during their cardiology training.

Free text responses (27 total)

Three major themes were elucidated:

1. Palliative care in heart failure is an important topic but not well covered in the curriculum (responses 5, 9, 11, 13, 15, 19, 21, 24, 25, 26).

- “Important and underemphasised aspect of cardiology. We like to think of ourselves as life savers, is that possibly why we don’t address the end-stage heart failure issues so well.” (response 9)

- “No culture of palliative care in Cardiology so this will NOT be picked up by trainees whilst on the job.” (response 12)

2. The palliation of patients is often not optimal (responses 3, 13, 27).

- Communication can be poor (responses 6, 27)

- Teams can find it difficult to accept that patients are dying (responses 3, 9, 17, 20, 27)

- “I think palliation of end-stage heart failure patients is generally poorly done and not thought of soon enough. I would value more training in this area as a heart failure fellow.” (response 3)

- “Heart failure is often badly palliated and patients are looked after by different teams, e.g. care of elderly and cardiology. In cardiology, I have encountered a systemic reluctance to accept that patients are dying and instead subjecting them to CCU based inotropes, etc.” (response 27)

3. Improved communication links are needed between the two specialities (responses 6, 7, 16, 17, 21, 22).

- “Nowhere near enough interaction between palliative care and cardiology. Not a lack of goodwill or interest, but mainly of funding and time. Too much palliative care funding focused on cancer. Too much cardiology funding focused on preventing hospital admission.” (response 7)

- “We need to make palliative care physicians more interested and accessible to cardiac patients.” (response 16)

- “I think cardiology trainees should be better trained in recognition of the need for palliative care input but I also think that palliative care trainees should be trained significantly in non-cancer related palliation.” (response 22)

Discussion

Due to the lack of confidence of trainees, this survey demonstrates that the majority of cardiology trainees continue to experience difficulties in providing good quality palliative care for patients with advanced heart failure with only approximately half of patients being referred to palliative care services. The barriers to obtaining palliative care input for advanced heart failure patients were not investigated in this survey but free-text responses suggest these are multi-factorial, and may include a cultural reluctance of cardiologists to accept that patients have reached a stage in their heart failure journey that may benefit from palliative care input, as well as difficulties in accessing palliative care services due to lack of the necessary infrastructure/funding. As a result, only a minority of respondents felt that the care they provided their end-stage heart failure patients was good. Over half of the trainees surveyed felt ill-equipped to discuss advanced-care planning and end-of-life issues when seeing advanced heart failure patients in an outpatient setting, with time pressures and a lack of the appropriate nursing support cited as possible obstacles to this.

Confidence in prescribing the medications commonly used in palliating advanced heart failure symptoms is low. Depression is common in heart failure and is associated with a worse clinical status and poor prognosis in heart failure.2 It is, therefore, of concern that only 4% of trainees prescribe these medications regularly, and 48% report that they never prescribe them. Opioids, anti-emetics and laxatives play a central role in symptom control in advanced heart failure, yet prescriptions of these medications were low. Both opioid titration and symptom control were identified in the survey as areas that trainees would prioritise for future teaching.

Advanced care planning takes into account the patient’s preference for place of death and their resuscitation decisions, including possible deactivation of an ICD. This is a key part of end-of-life care and, yet, this survey has shown that only 9.4% of trainees involved in the insertion of ICDs always explained the possibility of future deactivation of the device, with a significant proportion of trainees never raising this issue before implantation.8 It is increasingly believed that communication about ICD deactivation should be an ongoing process that begins prior to implantation and continues over time as the patient’s health status changes.9 Studies have indicated that, although physicians believe they should engage in these types of conversations with patients, they rarely do.10 Encouraging attendance at advanced communication courses may be a way of increasing trainees’ confidence in managing more difficult conversations with patients.

Despite the inclusion of end-of-life care in the cardiology curriculum, many trainees have not received the level of training that is necessary to achieve the specified competencies, and are not happy with the level of training and supervision given in this area. Workplace-based assessments are undertaken by only a minority of trainees. Trainees, who may lack the competencies to manage end-of-life care appropriately, deny their patients and their family/carers the holistic, multi-disciplinary care that they should receive, and this should be of grave concern to all cardiologists. So what can be done to overcome these issues?

More emphasis should be placed on end-of-life care in daily clinical practice, and all trainees should engage actively in this area. The presence of heart failure teams, as recommended by the National Heart Failure Audit, who provide specialist expertise in managing this group of patients would contribute to improving trainees’ levels of experience and skill. Improving links with local palliative care teams would also be of benefit for both specialities; cardiology trainees would be given an opportunity to expand their experience of palliative care, while palliative care trainees may learn about the management of end-stage cardiac diseases. Fellowships/placements in palliative medicine could play a valuable part in equipping cardiology trainees with the practical skills needed. Involvement of palliative care teams at specialist heart failure multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meetings would also be a mechanism of enhancing trainees’ knowledge. Locally based, small, group sessions could be utilised to develop communication skills and how to deal sensitively and effectively with patients and their family/carers. On a more formal level, regional and national training days could provide an exceptional forum for national experts to teach on end-of-life care. Collaboration with organisations such as the British Heart Foundation and MacMillan could also facilitate focused teaching of both cardiology and palliative care trainees.

It is encouraging, however, that trainees appear to recognise the importance of end-of-life care in their training and are keen for more opportunities to expand their knowledge of palliative care in cardiology.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a novel study, exploring the knowledge, attitudes and skills of cardiologists in training in end-of-life care in the UK. Responses were obtained from trainees in all sub-specialities, across all training grades and from all but one deanery, making the findings relevant nationally. The survey employed various methods to seek information including fixed-choice responses and rating scales, as well as providing a free-text section.

As with all studies relying on voluntary participation, the findings of our survey may be biased by the level of response. While the response rate for this survey was very much in keeping for this type of study, we acknowledge that only a relative minority of trainees did respond and, therefore, the results may not be accurate. In addition, the quantitative aspect of some of the questions used in the survey cannot accurately reflect the complex emotions/behaviours associated with this subject area. The levels of subjectivity of respondents cannot be assessed by this type of survey, i.e. what is ‘good’ care for one person, may be ‘bad’ care to another. However, the free-text responses did allow trainees an opportunity to expand their views in more depth.

Conclusion

This survey has demonstrated both a need for improved teaching and support for cardiologists in training in palliative care for heart failure patients. This could be provided by more local/national training days with a focus on end-of-life care, as well as local initiatives between cardiology and palliative care services to enhance both cardiology and palliative care trainees’ experience through communication skills workshops, fellowships or placements. In addition, collaboration with MacMillan and the British Heart Foundation to enhance trainees’ skills should be explored.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Ian Wilson, Dr Matthew Bates, and Dr Aaisha Opel for their help in distributing the survey to BJCA members and Professor Julia Addington-Hall for her help in preparing the survey questions.

Source of funding

Servier Laboratories funding for online survey support, data collection and analysis tool.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Editors’ note

See also the editorial by Johnson et al. in this issue.

Key messages

- The prognosis of chronic heart failure is equivalent to that of cancer yet only a small proportion of patients are referred to palliative care. To address this, the UK Cardiology curriculum includes end-of-life care within it

- This study demonstrates a need for improved teaching and support for UK Cardiology trainees in end-of-life care in heart failure

- Enhanced training for cardiologists using communication skills workshops, training days, fellowships or placements could improve the care delivered to this patient group

References

1. Connolly M, Beattie J, Walker D et al. End of life care in heart failure: a framework for implementation. Leicester: Heart Improvement Programme, NHS Improvement, 2010. Available from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/986/opendoc/177612

2. McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012; The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104

3. Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJV. More ‘malignant’ than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2000;3:315–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1388-9842(00)00141-0

4. The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. National heart failure audit. April 2011 and March 2012. London: National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR), 2012. Available from: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/heartfailure/documents/annualreports/hfannual11-12.pdf

5. Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Failure 2009;11:433–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041

6. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Specialty training curriculum for cardiology. London: Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board, August 2010. Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/Cardiology_curriculum_2010.pdf_32485140.pdf

7. McNulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 2008;33:301–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930701293231

8. Department of Health. Advance care planning: a guide for health and social care staff. Leicester: End of Life Care Programme, 2007. Available from: http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/AdvanceCarePlanning.pdf

9. Lampert R, Hayes DL, Annas GJ et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1008–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.04.033

10. Goldstein NE, Lampert R, Bradley E et al. Management of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:835–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00006