Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) can be defined as tachycardia with or without hypotension in the upright posture, and more comprehensively as a manifestation of a wider dysautonomia. The scope of this article is to characterise patients with PoTS and look at patient-rated responses to treatment.

This research comprised a postal survey, sent to patients with diagnosed PoTS at a tertiary hospital in Southwest England. We collected data on the demographics of patients, time to diagnosis, methods of diagnosis, treatments and response to treatment.

PoTS has an impact on quality of life, with patients communicating a drop in quality of life from 7.5 to 3.75 on a 10-point scale. From 40 respondents, 29 patients describe their symptoms improving since diagnosis, with self-rated day-to-day function improving from 3.21 to 6.14 (on a 10-point scale) after initiating treatment.

Many patients experience a delay in receiving a diagnosis with PoTS, and present multiple times to a variety of healthcare professionals. With a simple bedside diagnostic test (sitting and standing heart rate), there is scope to improve the time taken from developing initial symptoms to diagnosis, treatment and an improvement in quality of life.

Introduction

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) can be defined simply as a persistent tachycardia, with or without hypotension in the upright posture,1 with symptoms of orthostatic intolerance.2 Diagnosis varies depending on each centre, and may include the three-minute sit-to-stand test, 10-minute lie-to-stand test and/or tilt-table testing. A persistent heart rate rise of 30 or greater in the context of eliciting symptoms of orthostatic intolerance is usually considered diagnostic. It was officially recognised in 1993, but had previously existed under other names including soldier’s heart, Da Costa syndrome, irritable heart and idiopathic orthostatic intolerance.3 A more comprehensive definition is that PoTS is one manifestation of a wider dysautonomia, in which inappropriate tachycardia in the upright posture is accompanied by a myriad of other symptoms including (but not limited to); fatigue, migraine, gastroparesis, altered bowel habit, decreased cognitive function, syncope, palpitations, temperature disturbance, changes in sweating and sleep difficulties.4 These symptoms can be as a consequence of cerebral hypoperfusion and autonomic overactivity, and in PoTS these symptoms will be eased and may disappear with recumbency.5 The scope of this article is to build on the work of Deb et al.4 and Kavi et al.6 in characterising patients with PoTS and looking at patient-rated responses to treatments.

Method

This research comprised of a postal survey, sent to patients registered with a diagnosis of PoTS at a tertiary hospital in Southwest England. The results were anonymised, and respondents were not obliged to respond. We collected data on the demographics of patients, time to diagnosis, methods of diagnosis, treatments used and responses to treatment. We also assessed quality-of-life parameters before and after developing symptoms and receiving treatment. A simple 0–10 self-rated parameter was used to subjectively assess quality of life before and after treatment.

Results

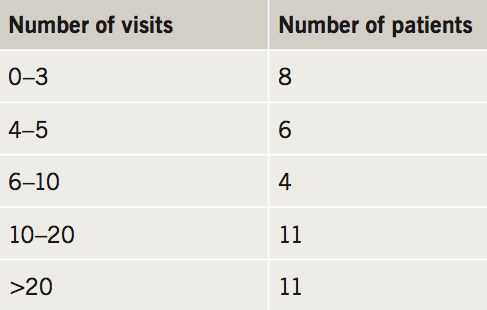

There were a total of 40 respondents, seven of whom were male and 33 female. There was an age range from 17 to 71 years old, with a mean age of respondents of 33.05 years. There were 21 either studying or in employment, and 14 had achieved an undergraduate and/or postgraduate qualification. Patients recruited had received a diagnosis of PoTS between six months and 38 years prior to the study. Many patients had experienced long delays between first developing symptoms and being diagnosed with PoTS, with nearly half (16 patients) experiencing a delay of greater than four years between onset of symptoms and diagnosis (table 1). Many presented to their GP or hospital consultants multiple times before a diagnosis was made, with 22 patients visiting their GP more than 10 times and 11 patients visiting hospital consultants on more than 10 occasions (table 2 and table 3). Diagnosis was made by a wide range of specialties with most patients (n=31) diagnosed by acute physicians and cardiologists (table 4). Over half of patients (n=23) were diagnosed by measuring sitting and standing heart rate, with others going on to be diagnosed by tilt-table testing.

The exact constellation of symptoms varied from patient to patient. Every patient responding to the survey was experiencing dizziness and fatigue, with many others experiencing; temporary cognitive dysfunction (‘brain fog’) (n=38), palpitations (n=37), nausea/vomiting (n=34), temperature disturbance (n=33), headaches (n=32), sleep disturbance (n=31), tremor (n=30), chest pain (n=30), visual changes (n=28), bloating (n=28), syncope (n=28), gastro-oesophageal reflux (n=23), bladder disturbance (n=20), diarrhoea (n=20), constipation (n=19), migraine (n=17) and a reduction in sweating (n=3). A total of 18 patients (45%) had injured themselves directly as a consequence of PoTS.

PoTS has an impact on quality of life, with patients communicating a drop in quality of life from 7.5 to 3.75 on a 10-point scale. Many patients would receive other diagnoses before being diagnosed with PoTS, these are listed with their respective frequencies in table 5. What we have found supports the study from Hoad et al.7 showing a correlation between patients diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome who are also found to have PoTS. Of patients, 29 think their symptoms have improved since being diagnosed and self-rated day-to-day function improved from 3.21 to 6.14 (on a 10-point scale) after initiating treatment.

Treatment strategies varied between patients, and reflects the variation in symptoms in each PoTS patient. Most were given lifestyle advice, with 33 being advised to avoid prolonged periods of standing, 32 to increase their dietary salt intake, 29 to increase their daily fluid intake and five advised to wear compression stockings. There were 19 patients medically treated with ivabridine, eight with midodrine, five with a beta blocker and two with fludrocortisone.

Many factors were common in exacerbating symptoms, with 35 reporting symptoms to be worse after exertion, 34 with exercise, 33 with hot temperatures and 29 after meals.

Discussion

PoTS is a disorder that must be looked at as more than merely an increased heart rate on standing. As demonstrated with this group of patients, it encompasses a wide range of symptoms affecting multiple organ systems. Many patients experience a delay in receiving a diagnosis with PoTS, and present multiple times to a variety of healthcare professionals. With simple non-invasive bedside diagnostic tests (such as the three-minute sit-to-stand and 10-minute lie-to-stand test), there is scope to improve the time taken from developing initial symptoms to diagnosis – with opportunities for clinicians from multiple specialties including general practice to diagnose PoTS (tilt-table testing could be reserved for patients with a convincing history and equivocal test results). With effective treatment options, symptomatic relief can be provided and an improvement made to quality of life in these patients.

Three-quarters of patients were diagnosed by acute physicians or cardiologists in this single-centre study. It must be noted that this may differ in other centres depending on the staff skill mix of the PoTS/autonomic clinics in each area. A more comprehensive assessment of specialists diagnosing PoTS could be obtained in a multi-centre study. Given the non-invasive nature of the validated diagnostic tests, their ability to be undertaken without specialist equipment and the number of presentations these patients often make to general practice, it may be possible for an increased proportion of diagnoses to be undertaken in primary care. Many patients had received alternative diagnoses prior to being found to have PoTS. While many of these conditions may be concurrent (in particular Ehlers-Danlos and hypermobility), where there is diagnostic uncertainty with patients presenting with palpitations, dizziness and fatigue, a screening three-minute sit-to-stand or 10-minute lie-to-stand test should be considered.

Limitations from this study include its retrospective nature. A useful development would be to survey patients at the time of diagnosis (prior to treatment) and then following treatment to more accurately assess changes to quality of life. Here we have used a self-rated 10-point scale to attempt to quantify quality of life, a complex parameter comprising of biological aspects (symptom control), psychological aspects (the patients self-rated quality of life) and social aspects (their ability to contribute to work, social and family life). Another limitation is the small sample size, a larger multi-centre study could be used to consider the statistical significance of these results.

What is not yet understood are the direct causative mechanisms of PoTS, and until then it is likely that a varied approach to treatments, depending on an individual symptom profile, will need to be taken. We have demonstrated in this small study how varied the demographics can be in patients developing PoTS, and the diagnosis should be considered in any patients presenting with dizziness and fatigue. Furthermore, the diagnostic test (such as a three-minute sit-to-stand or 10-minute lie-to-stand) could be considered to screen patients at chronic fatigue services – as many patients are often misdiagnosed, and as demonstrated in this study, symptomatic treatment in PoTS can lead to an improvement in quality of life.

Key messages

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) is a manifestation of dysautonomia, which has a demonstrable impact on quality of life for patients

- Treatments vary from lifestyle modifications and dietary changes to pharmacological interventions such as slow sodium, ivabradine, beta blockers, midodrine and fludrocortisone

- Treatments should be tailored to each individual patient, and the symptoms that are having greatest impact on their quality of life

- With effective management, self-rated quality of life can return closely to pre-symptomatic levels.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Samuels MA, Pomerantz BJ, Sadow PM. Case 14-2010: A 54-year-old woman with dizziness and falls. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1815–23. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcpc0910070

2. Plash WB, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I et al. Diagnosing postural tachycardia syndrome: comparison of tilt test versus standing hemodynamics. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:109–14. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20120276

3. Kavi L, Gammage M, Grubb B, Karabin B. Postural tachycardia syndrome: multiple symptoms, but easily missed. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:286–7. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X648963

4. Deb A, Morgenshtern K, Culbertson C, Lang W, DePold Hohler A. A survey-based analysis of symptoms in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2015;28:157–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2015.11929217

5. Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci 2011;161:46–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2011.02.004

6. Kavi L, Nuttall M, Low D et al. A profile of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome and their experience of healthcare in the UK. Br J Cardiol 2016;23:33. https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2016.010

7. Hoad A, Spickett G, Elliott J, Newton J. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is an under-recognized condition in chronic fatigue syndrome. Q J Med 2008;101:961–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcn123