Pericardial cyst is a rare diagnosis, mainly considered a congenital condition. Most patients with pericardial cysts present without symptoms. Symptomatic presentation often relates to the size and location of the pericardial cyst. We report a case of a 49-year-old man who presented with subacute breathlessness in which the diagnosis of a pericardial cyst was made following various investigations – from transthoracic echocardiography and computed tomography scan to video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery biopsy, upon which a histological diagnosis was made. This case report reviews and discusses the available literature on the epidemiology and potential presenting features of a pericardial cyst, and the current recommended assessment and management strategies thereof. This case highlights the importance of effective multidisciplinary communication and joint input towards clinical decision-making, particularly in complex scenarios, to achieve optimal patient outcomes.

Case presentation

A 49-year-old man presented with a four-day history of progressive breathlessness and chest tightness. Breathlessness was exacerbated by deep inspiration and mild exertion. The patient reported reduced exercise tolerance compared to his baseline, together with lethargy, loss of appetite, intermittent fever, and night sweats during the preceding two weeks. There was no significant past medical history or recent surgery. However, he reported an extensive travel history to the Himalayas. Physical examination revealed a sinus tachycardia without further notable findings.

Investigations showed a neutrophilic leucocytosis (white blood cell count: 11.5 x 109 cells/L [reference range: 4–11 x 109 cells/L]) alongside raised inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein: 113.5 mg/L). Two sets of troponin T levels were within normal range (<14 ng/L). N-terminal of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels were unremarkable. Blood and urine cultures were both negative. Electrocardiography (ECG) revealed T-wave inversions in leads II, III, and aVF, while chest X-ray (CXR) displayed minimal bilateral pleural effusions. Investigations for tuberculosis were negative. The patient was preliminarily managed for sepsis of an unknown source with intravenous cefuroxime 1.5 g three times daily for six days.

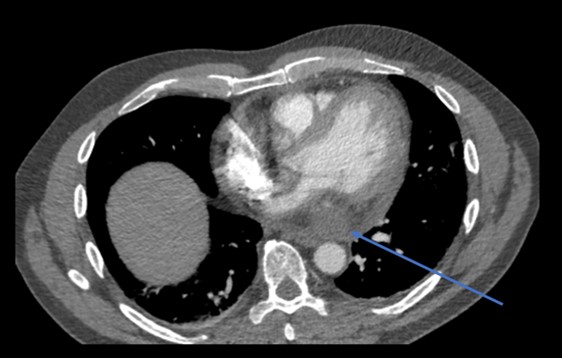

Considering the patient’s clinical presentation, a contrasted chest computed tomography (CT) scan was requested to rule out pulmonary embolism. Meanwhile, a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was also performed, which noted the presence of a small mass within the pericardium near the left atrium and a small rim of pericardial effusion that appeared non-compromising (figure 1). There was normal left ventricular function with an ejection fraction >55% and no significant valvular abnormality. However, the right ventricular systolic function was impaired. Contrasted chest CT identified an oval 7 cm × 8 cm soft tissue lesion in the posteroinferior aspect of the mediastinum (figures 2 and 3). The mass lay within the pericardium but appeared separate from the myocardium, the oesophagus, the aorta and the inferior vena cava. There was no evidence of pulmonary embolism nor other suspicious masses. A subsequent position emission tomography (PET) CT scan was recommended to assess the posterior pericardial soft tissue mass. The scan showed that the mass was non-FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) avid, suggesting that it was of benign aetiology. There was no evidence of any primary or secondary tumour elsewhere. The case was discussed with the cardiothoracic surgery team; due to the mass’ posterior pericardial position, the decision was made to proceed to obtain a biopsy thereof using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Extensive pericardial adhesions around the mass were noted, which were likely related to previous cystic ruptures. The mass appeared to consist of multi-loculated, thick-walled cysts adherent to the left ventricular epicardium. It was challenging to get into a plane between the mass and the actual epicardium of the left ventricle. Subsequently, it was decided to unroof the cysts and form a pericardial window whereby cystic fluid could drain into the left pleural cavity.

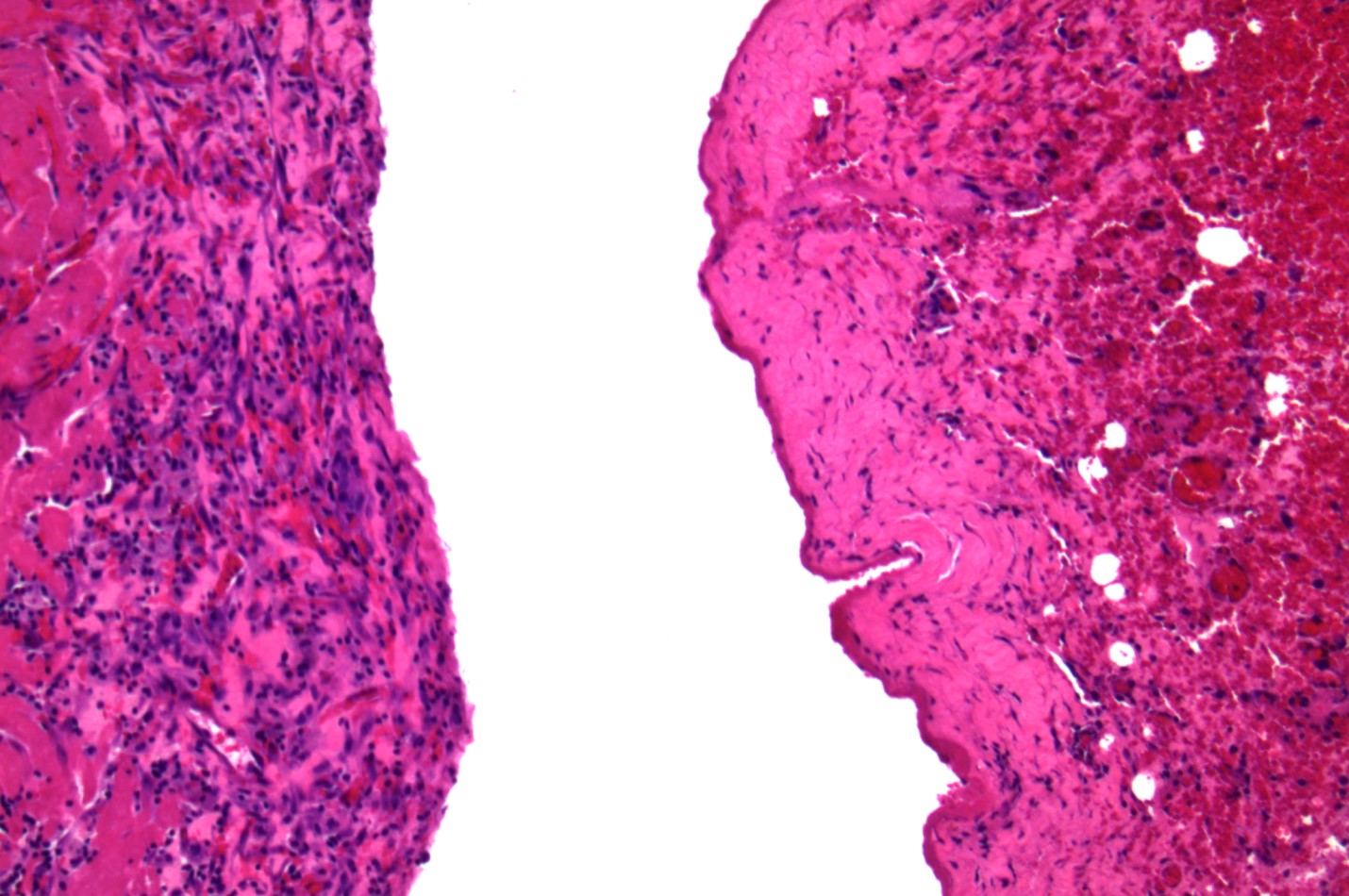

Samples obtained from the cyst wall and cyst fluid were sent for histological examination, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and microbiological culture. Histology of the cyst wall was suggestive of fibrosis (figure 4). No infective pathogens were identified, nor were any malignancies found on histopathology. The multidisciplinary histopathology team further evaluated the cyst wall histology sample, and given the clinical correlation of this case, it was concluded that this was most likely a congenital pericardial cyst, and spontaneous haemorrhage into the pericardial cyst led to the patient’s acute presentation. Additionally, a hydatid cyst was one of the suggested differential diagnoses, supported by the travel history mentioned.

Nevertheless, after the VATS procedure and medical management (including colchicine, low-dose beta-blocker and gabapentin), the patient gradually recovered to his usual functional baseline status and was discharged to the community for cardiac rehabilitation. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) six months after discharge showed that the cyst along the basal inferior wall had completely resolved and there was no visible cyst, though there was some pericardial scarring close to the area where the biopsy was taken.

Discussion

Pericardial cysts are a rare phenomenon often found incidentally as 50–75% of cases are asymptomatic and are diagnosed during investigations for other reasons.1 Symptomatic presentation depends on the location and size of the lesion.2 Common symptomatic complaints include recurrent chest pains, persistent shortness of breath, cough and dysphagia. Unusual presentations can involve recurrent syncope and heart failure. Complications include compression on surrounding structures, inflammation, cardiac tamponade due to rupture within the pericardium or haemorrhage within the cyst, etc. However, no data about the incidence of complications is currently available.3–7

Considered a congenital anomaly, the incidence of pericardial cysts is about 1 per 100,000.4 Pericardial cysts represent approximately 6–7% of all mediastinal masses, with over 75% presenting as right-sided masses; approximately 22% appear as left-sided masses.3,4 There is no sex predisposition and current literature on its age distribution is not suggestive of a well-defined trend.

Imaging workup should include a CXR, followed by TTE and a chest CT scan before MRI.

For asymptomatic patients, close follow-up with regular imaging is recommended.1,9 Invasive treatment is not recommended as a prophylactic measure in asymptomatic patients. For patients with symptoms, surgical treatment options for pericardial cysts may include the removal of cysts through open surgery, endoscopic resection with VATS or percutaneous echocardiography-guided aspiration.4,9,10 Deciding between surgical versus conservative management and modality of operative treatment depends on various factors – size and location of the pericardial cysts, risks versus benefits of an invasive approach, availability of expertise, and patient preference.

Ethanol sclerosis has been reportedly used as a treatment for liver and kidney cysts; a case study reported the use thereof to treat a pericardial cyst.11,12 A percutaneous pigtail catheter was inserted under echocardiographic guidance to insert concentrated ethanol into the cyst cavity and irrigated with 0.9% saline. The treatment was successful, with no recurrence observed at six-month follow-up. Complications included chest pain due to irritation of the pericardial nerves, which was managed with intra-cyst injection of lidocaine. Another potentially serious complication, an ethanol leak into the pericardium, was mitigated by contrast injection into the cyst to ensure that there was no communication between the cyst and the pericardial cavity.13 Current evidence does not appear to lean towards any particular treatment; hence treatment decisions should be individualised. However, surgical treatment is recommended for patients with rapidly growing cysts, severe symptoms and acute complications from pericardial cysts.1–4,7,9 Complete excision of pericardial cysts is recommended during surgery to minimise the recurrence rate.1–7 The holistic approach for patients is always valuable; small details like travel history can explain and guide differential diagnosis.

Conclusion

This case emphasises the importance of a stepwise systematic approach to investigating the causes of breathlessness to ensure that even the most unusual differentials are investigated. Holistic, multidisciplinary decision-making is essential to ensure that clinicians act in the patient’s best interests and balance the risks and benefits of the treatment options in situations where clear-cut guidance is unavailable. Hopefully, with further case reporting of pericardial cysts, evidence-based guidance on the management thereof could be established.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Statement of consent

Full written patient informed consent was obtained.

References

1. Varvarousis D, Tampakis K, Dremetsikas K et al. Pericardial cyst: an unusual cause of chest pain. J Cardiol Cases 2015;12:130–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccase.2015.06.003

2. Bhattacharya R. Pericardial cyst: a review of historical perspective and current concept of diagnosis and management. Interv Cardiol J 2015;1:1–8. https://doi.org/10.21767/2471-8157.10008

3. Najib MQ, Chaliki HP, Raizada A et al. Symptomatic pericardial cyst: a case series. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011;12:E43. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jer160

4. Patel J, Park C, Michaels J et al. Pericardial cyst: case reports and a literature review. Echocardiography 2004;21:269–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0742-2822.2004.03097.x

5. Lau CL, Davis RD. The Mediastinum. In: Townsend Jr. MD, Courtney M, Beauchamp MD et al (eds). Sabiston’s Textbook of Surgery, 17th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; pp. 1738–58.

6. Hynes JK, Tajik AJ, Osborn MJ et al. Two-dimensional echocardiographic diagnosis of pericardial cyst. Mayo Clin Proc 1983;58:60–3.

7. Kar SK, Ganguly T. Current concepts of diagnosis and management of pericardial cysts. Indian Heart J 2017;69:364–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2017.02.021

8. Strollo DC, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Jett JR. Primary mediastinal tumors: part II. Tumors of the middle and posterior mediastinum. Chest 1997;112:1344–57. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.112.5.1344

9. Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary: the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2004;25:587–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002

10. Mouroux J, Venissac N, Leo F et al. Usual and unusual locations of intrathoracic mesothelial cysts. Is endoscopic resection always possible? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;24:684–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00505-0

11. Blonski WC, Campbell MS, Faust T, Metz DC. Successful aspiration and ethanol sclerosis of a large, symptomatic, simple liver cyst: case presentation and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:2949–54. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i18.2949

12. Mohsen T, Gomha MA. Treatment of symptomatic simple renal cysts by percutaneous aspiration and ethanol sclerotherapy. BJU Int 2005;96:1369–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05851.x

13. Kinoshita Y, Shimada T, Murakami Y et al. Ethanol sclerosis can be a safe and useful treatment for pericardial cyst. Clin Cardiol 1996;19:833–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960191015