Coronary artery spasm (CAS), or Prinzmetal angina, is a recognised cause of myocardial ischaemia in non-obstructed coronary arteries which typically presents with anginal chest pain. This case report describes an atypical presentation of CAS in a 68-year-old white British male with cardiovascular risk factors. The patient presented with recurrent palpitations and pre-syncope, with no chest pain. Ambulatory electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring revealed recurrent polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PMVT). Coronary angiography identified moderate stenosis of the right coronary artery (RCA), without significant flow restriction by invasive pressure wire interrogation.

Inpatient monitoring revealed episodes of recurrent PMVT coinciding with transient inferior ST elevation and a distinct ‘shark fin’ waveform, indicating dynamic RCA occlusion. The arrhythmias persisted despite initial medical management, including calcium channel blockers and intravenous glyceryl trinitrate. Percutaneous coronary intervention to the moderate RCA lesion was performed, which definitively treated the arrhythmias.

This case emphasises the importance of recognising plaque-associated CAS as a potential trigger for life-threatening arrhythmias, even in the absence of chest pain. While medical therapy remains first-line treatment, life-threatening presentations may necessitate invasive interventions to stabilise the patient and prevent recurrence.

Introduction

Coronary artery spasm (CAS), or Prinzmetal angina, is an increasingly recognised cause of myocardial ischaemia in non-obstructed coronary arteries. It typically presents with anginal chest pain.1 It is rarely associated with myocardial infarction and symptomatic arrythmias.2 It occurs primarily at rest, most commonly in the morning,1,3 and is mostly observed in 40–70-year-old males.4 Prevalence varies by ethnicity, with Japanese ethnicity most strongly linked.5 Atherosclerotic coronary stenosis is an independent risk factor for CAS; more diseased vessels have a higher tendency to spasm in ergonovine provocation testing.6 We describe an unusual case of CAS presenting with recurrent palpitations due to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PMVT), without chest pain.

Case report

A 68-year-old white British male smoker with hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and stage 0 chronic lymphocytic leukaemia presented with a two-month history of recurrent non-exertional palpitations occurring mostly in the morning. He had several presyncopal episodes without chest pain. His only regular medication was lercanidipine. An outpatient 24-hour, three-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed one-to-two-minute runs of PMVT, prompting admission for work-up.

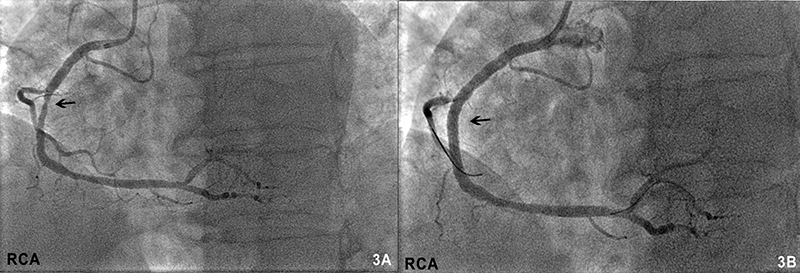

Serum potassium, magnesium, calcium, and high-sensitivity troponin I (hsTnI) were normal. Resting ECG showed a sinus bradycardia of 47 beats per minute (bpm) with a QTc interval of 430 ms. Echocardiography was normal. Invasive coronary angiography demonstrated a visually moderate-to-severe stenosis in the mid-segment of the dominant right coronary artery (RCA) without flow restriction on serial pressure wire assessment (instantaneous wave-free ratio 0.94, fractional flow reserve 0.83). The left coronary system was atheromatous but unobstructed.

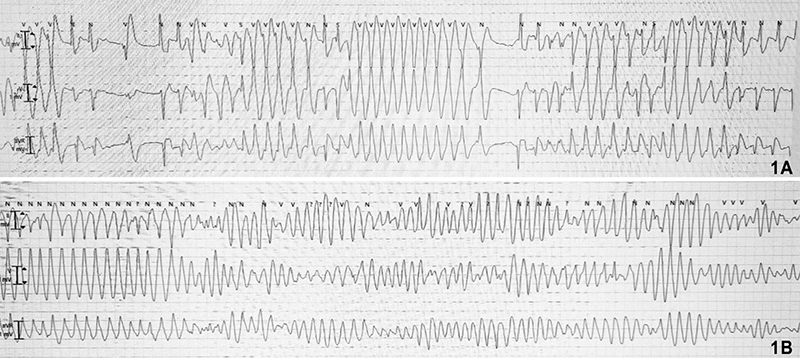

While awaiting inpatient cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, the patient had a storm of PMVT runs (figure 1A). Remarkably, he was minimally symptomatic, besides palpitations, until a protracted episode of PMVT (figure 1B) caused a loss of cardiac output requiring defibrillation.

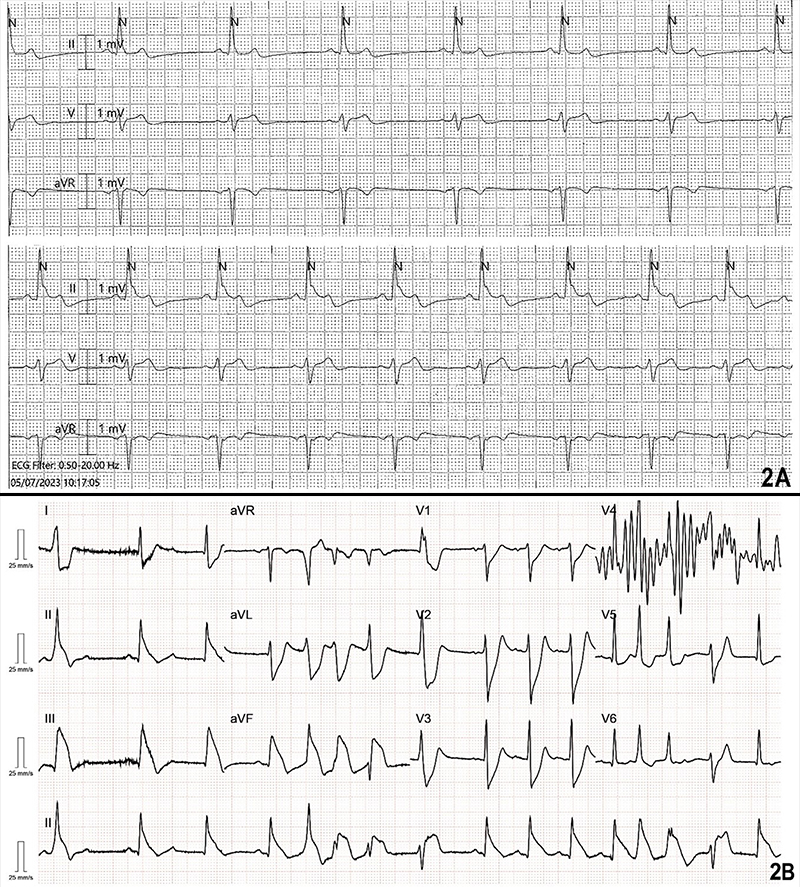

The PMVT runs recurred despite intravenous magnesium infusion. Telemetry review of their onset showed no preceding pauses or significant bradycardia; however, there was progressive ST elevation in lead II evolving for about a minute before each episode. Subsequent continuous 12-lead ECG recording revealed transient inferior ST elevation with probable posterior extension and a distinctive ‘shark fin’ pattern (figure 2) during these periods.

The PMVT continued despite an intravenous amiodarone bolus of 300 mg and a glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) infusion at 4 mg/hr; it subsided after maximising the GTN infusion and doubling the dose of the patient’s lercanidipine.

The hsTnI (normal range <14 ng/L) was mildly raised at 176 ng/L three hours post-defibrillation but decreased to 148 ng/L six hours post-defibrillation. Repeat 12-lead ECG showed complete resolution of the ST elevation. Bedside echocardiogram showed only subtle inferoposterior hypokinesia. Repeat invasive coronary angiography three days later showed no change in the mid-RCA stenosis (figure 3A). As spasm superimposed on this lesion was deemed the most probable cause clinically, repeat pressure wire study or provocative testing was not performed and the RCA lesion was treated with a drug-eluting stent (figure 3B). Plaque rupture was also included as a differential diagnosis; however, given the recurrent episodes, was considered less likely.

Retrospective re-analysis of the original 24-hour ECG revealed progressive ST elevation in lead III for about a minute before each PMVT run, confirming that the pre-hospital arrythmias were caused by dynamic RCA occlusion.

The patient had no further symptoms or arrhythmias for 48 hours post-coronary intervention and was subsequently discharged without an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. He remained asymptomatic at his six-month follow up.

Discussion

Usually, CAS presents with chest pain, but as this case demonstrated, it may present atypically with arrythmia only. While transient silent ischaemia is known to be common in vasospastic angina, painless ischaemia presenting with recurrent malignant ventricular arrythmia has rarely been reported.7–13 While torsade de pointes, a specific form of PMVT, occurs in the context of QT prolongation, PMVT with a normal QT interval is usually due to ischaemia or cardiomyopathy. In this pain-free patient with an overlooked dynamic ST elevation, overreliance on the negative coronary pressure wire study resulted in dismissing the possibility of superimposed CAS triggering the arrhythmia. Keeping an open mind of the potential differential diagnoses, maintaining a high index of suspicion for ischaemia, and careful analysis of repolarisation on the rhythm strips enabled definitive diagnosis and treatment in this case. Calcium channel blockers continue to be the primary treatment for variant angina,14 however, the occurrence of life-threatening arrhythmias necessitates an invasive treatment approach.

Conclusion

CAS can occur at the atherosclerotic plaque site and can be successfully treated with percutaneous coronary intervention.9,10 Spasm-induced PMVT can present with deceivingly benign-sounding symptoms. When PMVT without QT prolongation is detected, a high index of suspicion for ischaemia should be maintained, and the preceding ST segment should be scrutinized for dynamic changes, including the ‘shark fin’ appearance – a deadly ECG waveform every physician should recognise.15

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Statement of consent

Full written patient informed consent was obtained.

References

1. Prinzmetal M, Kennamer R, Merliss R, Wada T, Bor N. Angina pectoris. I. A variant form of angina pectoris; preliminary report. Am J Med 1959;27:375–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(59)90003-8

2. Bory M, Pierron F, Panagides D, Bonnet JL, Yvorra S, Desfossez L. Coronary artery spasm in patients with normal or near-normal coronary arteries: long-term follow-up of 277 patients. Eur Heart J 1996;17:1015–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014996

3. Yasue H, Nakagawa H, Itoh T, Harada E, Mizuno Y. Coronary artery spasm – clinical features, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Cardiol 2008;51:2–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.01.001

4. Matta A, Bouisset F, Lhermusier T et al. Coronary artery spasm: new insights. J Interv Cardiol 2020;2020:5894586. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5894586

5. Hung M-J, Hu P, Hung M-Y. Coronary artery spasm: review and update. Int J Med Sci 2014;11:1161–71. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.9623

6. Jo S-H, Sim JH, Baek SH. Coronary plaque characteristics and cut-off stenosis for developing spasm in patients with vasospastic angina. Sci Rep 2020;10:5707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62670-z

7. Egashira K, Araki H, Takeshita A, Nakamura N. Silent myocardial ischemia in patients with variant angina: panel discussion on silent myocardial ischemia. Jpn Circ J 1989;53:1452–7. https://doi.org/10.1253/jcj.53.1452

8. Kaku B, Katsuda S, Taguchi T. Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia due to silent coronary artery spasm: usefulness of I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy for detecting coronary artery spasm in the era of automated external defibrillators: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2015;9:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-9-26

9. Kim SJ, Juong JY, Park T-H. Ventricular tachycardia-associated syncope in a patient of variant angina without chest pain. Korean Circ J 2016;46:102–6. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.46.1.102

10. Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Mallon SM et al. Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with silent myocardial ischemia due to coronary artery spasm. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1451–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199205283262202

11. Postorino C, Gallagher MM, Santini L et al. Coronary spasm: a case of transient ST elevation and syncopal ventricular tachycardia without angina. Europace 2007;9:568–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eum087

12. Somaschini A, Astuti M, Cordone S et al. Unusual syncope due to silent coronary vasospasm: a case description and an overview of coronary vasospasm. Cardiospace 2022;1:11–6. https://doi.org/10.55976/cds.1202215611-16

13. Sovari AA, Cesario D, Kocheril AG, Brugada R. Multiple episodes of ventricular tachycardia induced by silent coronary vasospasm. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2008;21:223–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-008-9207-4

14. Lanza GA, Shimokawa H. Management of coronary artery spasm. Eur Cardiol Rev 2023;18:e38. https://doi.org/10.15420/ecr.2022.47

15. Ghali S. ‘Shark Fin: a deadly ECG sign that you must know! 2018. Available from: https://hqmeded-ecg.blogspot.com/2018/06/shark-fin-deadly-ecg-sign-that-you-must.html (accessed January 2025)