Patients with diabetes are at particularly high risk for cardiovascular disease. Indeed diabetes has been appropriately described as ‘a state of premature cardiovascular death associated with chronic hyperglycaemia’.1 Recently, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) have published joint guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.2 Broadly, they reflect the rigorous approach of the 2005 revised Joint British Societies’ guidelines on the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Clinical Practice (JBS 2).3 In this article, we will revisit the main JBS 2 guidelines for individuals with diabetes and compare them with the recommendations from the ESC/EASD.

The need for new guidelines

The aim of the first guidelines from the Joint British Societies (JBS 1) was to promote a more effective multi-disciplinary approach to cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention.4 The guidelines addressed the needs of both individuals with established disease and apparently healthy subjects at high risk of developing disease. The National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) for England and Wales endorsed the lifestyle and risk factor targets in JBS 1.5 It also established national audit standards, which were subsequently reinforced and expanded by the General Medical Services contract for primary care.

Since then new data have been published on blood pressure and lipid lowering in people with established disease and those at high risk; on risk factor modification in diabetes; and on the prevention of diabetes. In particular, landmark trials of statin treatment rendered the JBS 1 guidelines on lipid lowering obsolete, and lower thresholds for commencing lipid-lowering therapy were recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, www.nice.org.uk). In the light of this new evidence the JBS guidelines were in need of revision.

Who needs intervention?

The aims of the revised guidance are broadly similar to those of its predecessor: CVD prevention for all high-risk people by reducing the risk of the disease and its complications – including the need for revascularisation procedures – and to improve quality of life and life expectancy. JBS 1 highlighted the specific problem of CHD but the new guidance encompasses the whole spectrum of atherosclerotic CVD. Since all these people have a high risk of death from CVD, especially from CHD, it is necessary to apply similar lifestyle and risk factor targets to the entire cohort.

JBS 2 therefore focuses equally on CVD prevention in all individuals at high risk:

- people with established atherosclerotic CVD

- those with diabetes

- apparently healthy individuals at high risk of developing symptomatic disease, i.e. CVD risk ≥ 20% over 10 years.

People in these three groups should all receive lifestyle and multi-factorial risk factor intervention to defined targets.

People with elevated single risk factors are also targeted for CVD risk reduction:

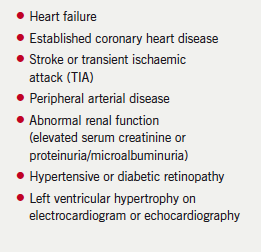

- elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure (≥ 160 mmHg and ≥ 100 mmHg, respectively) or lesser degrees of hypertension with target organ damage (box 1)

- elevated total to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio (≥ 6.0)

- familial dyslipidaemia.

Finally, those with a family history of premature CVD (men < 55 years and women < 65 years) should have their cardiovascular risk assessed and managed accordingly.

People with diabetes

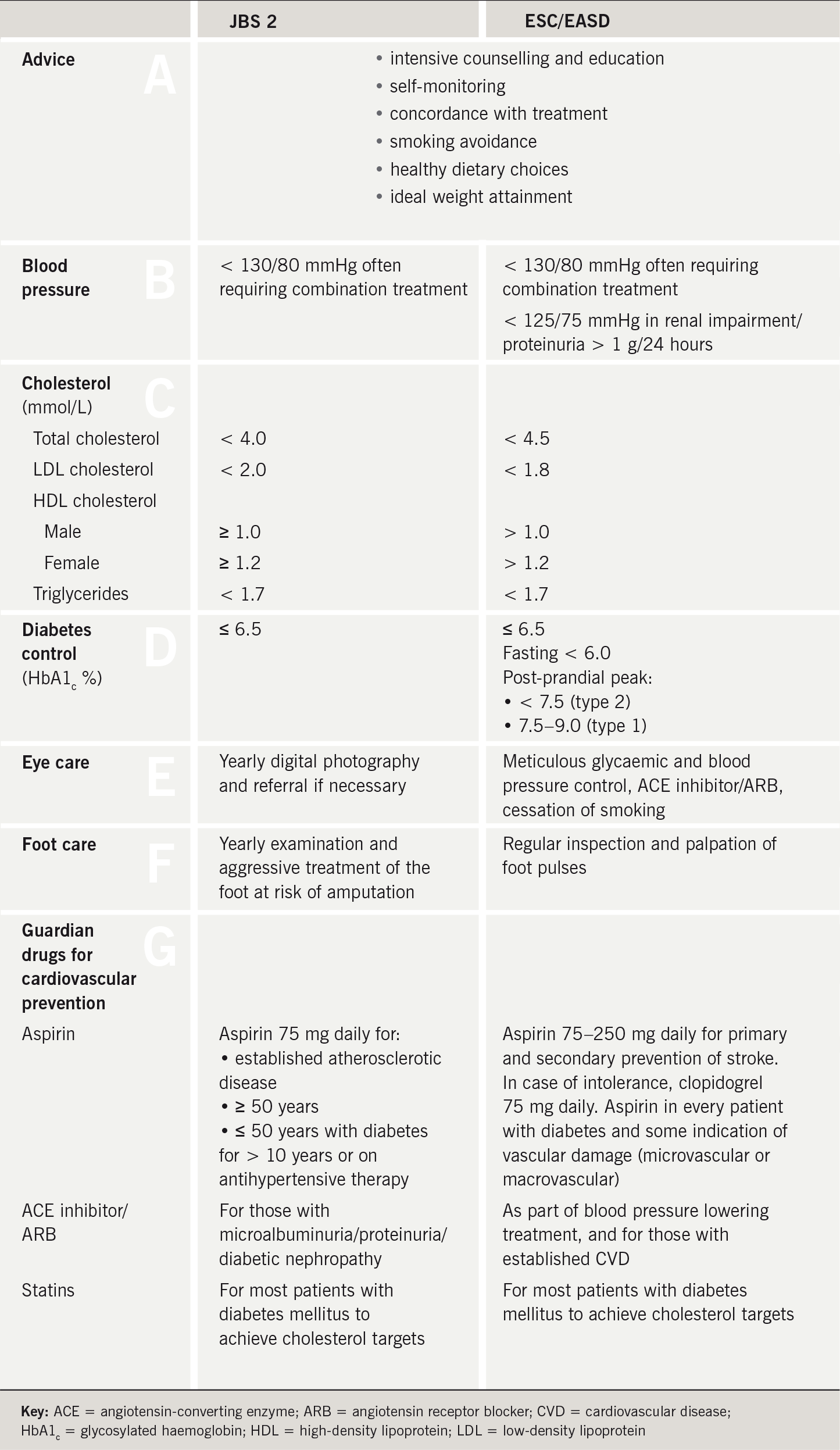

CHD risk calculation was previously recommended in patients with diabetes to inform commencement of treatment with blood pressure and lipid-lowering agents. However, since everybody with diabetes is at high CVD risk, and should be treated as such, these estimations are no longer used. In the sections that follow we use our Alphabet Strategy approach to summarise the key recommendations of JBS 2 and the main evidence underpinning them.6

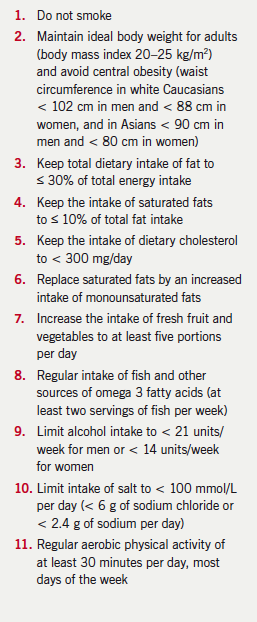

Advice

This includes education about the disease and its complications, empowering user self-management, and the importance of concordance with treatment and clinical review. Special attention is warranted for smoking cessation, appropriate dietary choices, physical activity and ideal weight attainment (box 2).

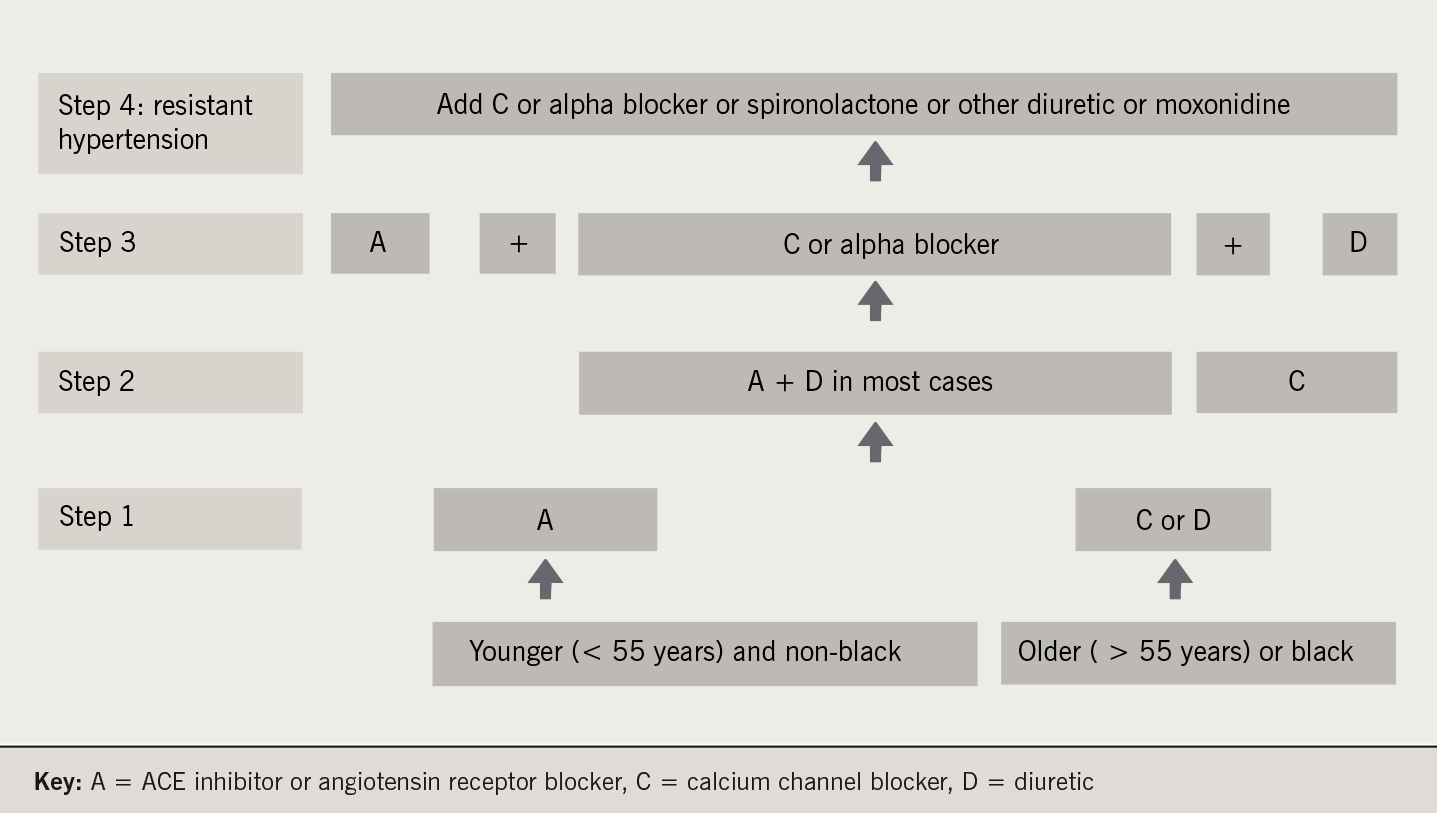

Blood pressure

JBS 2 reduces the target blood pressure in diabetes even further than previously to < 130/80 mmHg. This recommendation is based mainly on observational data rather than on extensive evidence from clinical trials. To achieve this target most patients require polypharmacy. The British Hypertension Society A/CD guidelines (figure 1) are a sound algorithm for blood pressure lowering in diabetes care, with a bias towards the A (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker) and D (diuretic) combination. Calcium channel blockers (C) are the preferred third-line agents. For resistant hypertension spironolactone, alpha blockers or centrally acting agents like moxonidine can be used. However, beta blockers (B) are no longer recommended unless there is some other indication for their use.7

Careful explanation of the benefits of treatment and vigilance for side effects are needed to maximise patient concordance.

Cholesterol

In a very significant departure from previous recommendations, JBS 2 suggests the following indications for

statin therapy:

- All those aged ≥ 40 years with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

- Those aged 18–39 years with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes who have at least one of:

- retinopathy (pre-proliferative, proliferative, or maculopathy)

- nephropathy, including persistent microalbuminuria

- poor glycaemic control (glycosylated haemoglobin [HbA1c] > 9%)

- elevated blood pressure requiring antihypertensive therapy

- raised total blood cholesterol (≥ 6.0 mmol/L)

- features of the metabolic syndrome (central obesity and hypertriglyceridaemia and/or low HDL cholesterol)

- family history of premature CVD in a first-degree relative.

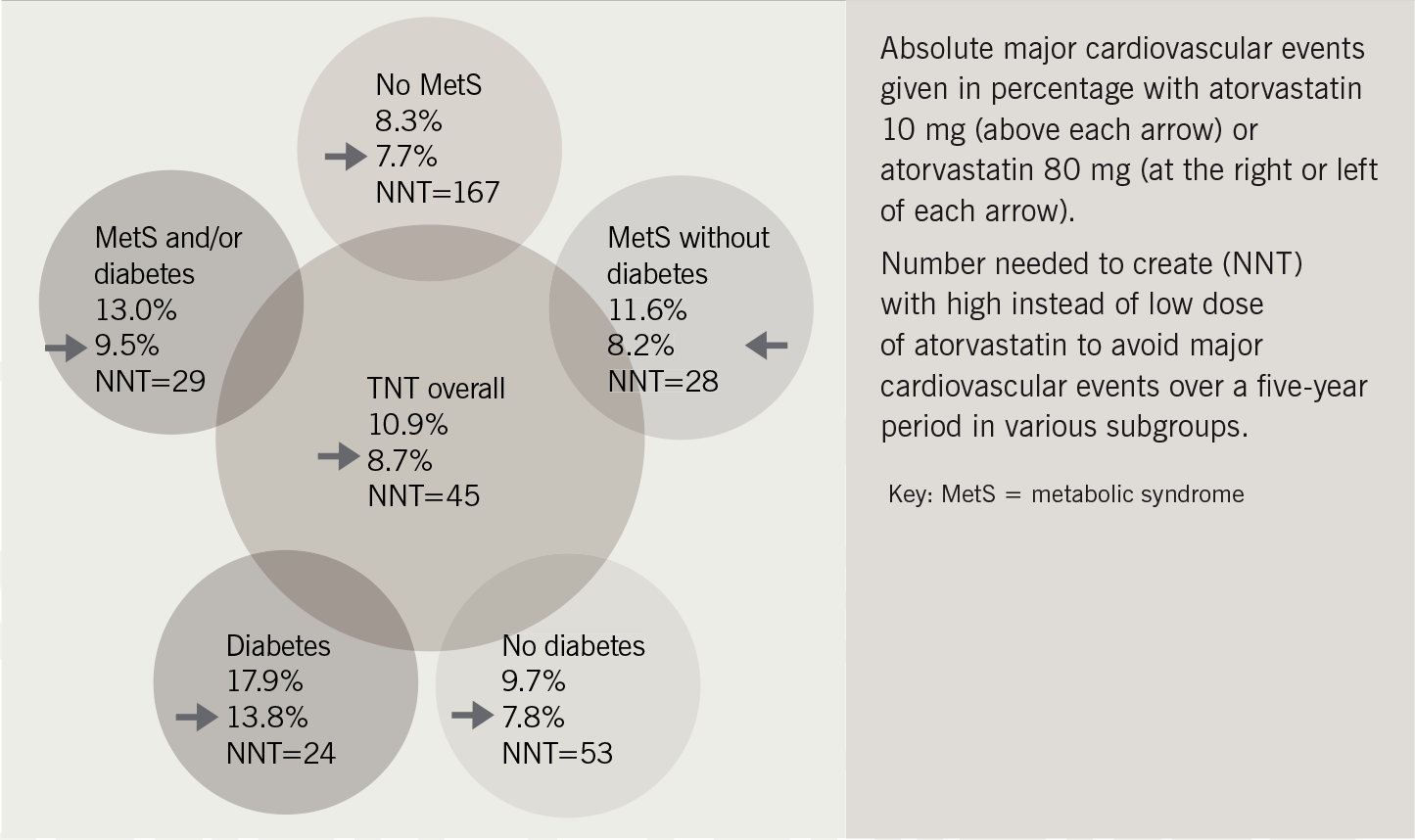

The targets suggested are total cholesterol ≤ 4 mmol/L and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol ≤ 2 mmol/L. This has been controversial. However, there is very good evidence for aggressive statin therapy from the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study: this showed that only 24 patients with diabetes and CVD needed to be treated to prevent one CVD event. By comparison, the numbers needed to treat were 53 for those without diabetes and 167 for those without the metabolic syndrome (figure 2).8

Lipid-lowering agents other than statins may be indicated in the following circumstances:

- in combination with a statin if total and LDL cholesterol targets are not met

- instead of a statin when the main abnormality is severe hypertriglyceridaemia (> 10 mmol/L)

- if statins are not tolerated.

Diabetes control

Tight glycaemic control remains crucial in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes to reduce microvascular and macrovascular complications. Ideally the goal is normoglycaemia with the avoidance of hypoglycaemia. Optimal biochemical targets are HbA1c < 6.0% and fasting or pre-prandial glucose levels of 4–6 mmol/L. The European Society of Cardiology/European for the Study of Diabetes (ESC/EASD) guidelines also draw attention to the need to control peak postprandial glucose levels.

Good glucose control in type 1 diabetes needs appropriate insulin therapy together with dietary and lifestyle adjustment. Rapid symptom relief may be achieved by use of twice-daily pre-mixed insulin, but good glycaemic control frequently requires a four-times-daily basal-bolus insulin regimen.

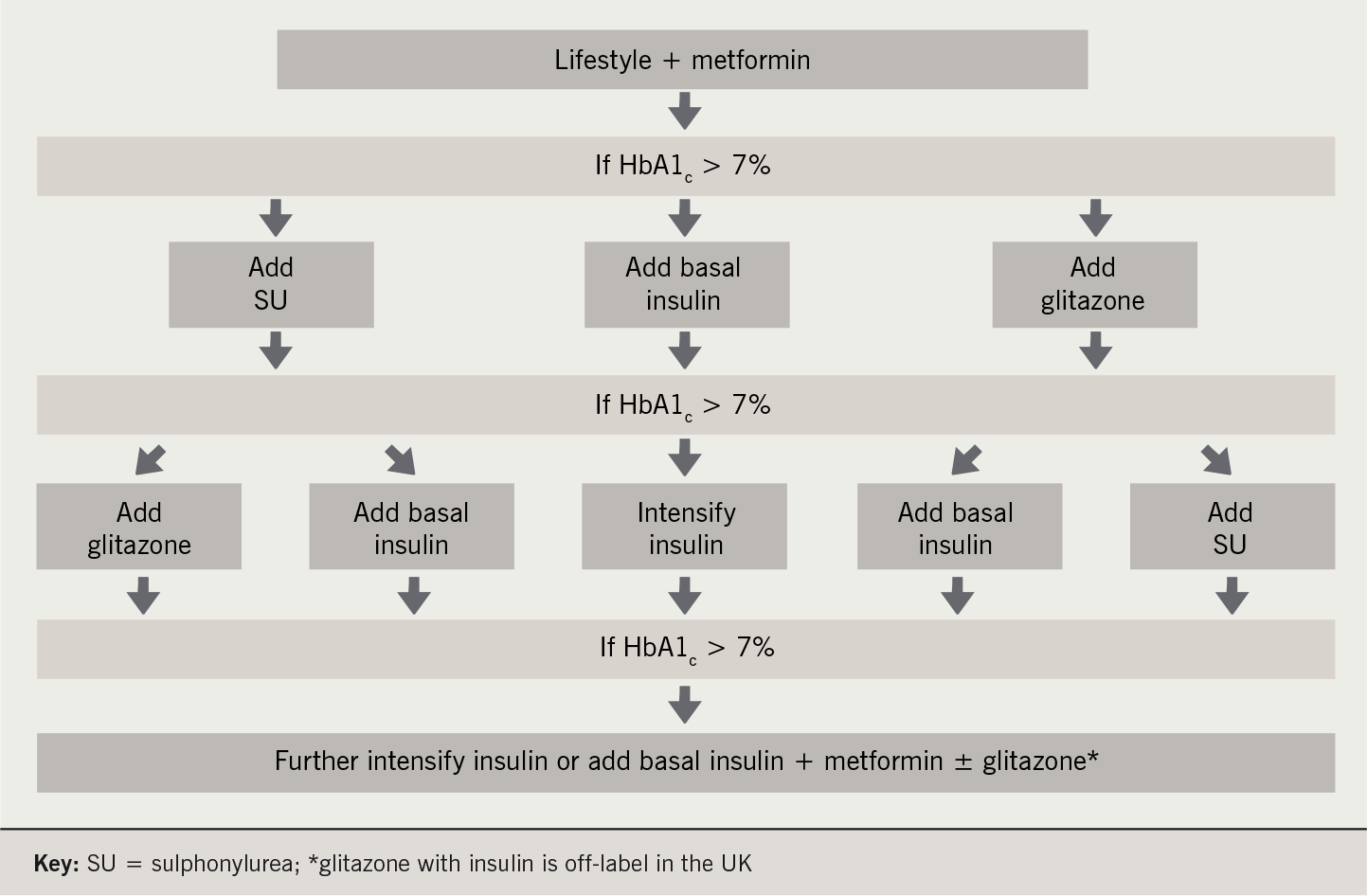

In type 2 diabetes, professional dietary advice, weight reduction, if necessary, and increased physical activity are the first steps to glycaemic control. However, many patients also need pharmaceutical intervention. The recently published American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) consensus algorithm should pave the way for much-needed agreement on how this should be undertaken (figure 3).9

Diabetes (ADA/EASD) algorithm for management of type 2 diabetes

The essential features of the algorithm are:

- HbA1c > 7% is a ‘call to action’ to intensify glucose-lowering therapy

- lifestyle modification and metformin are the initial interventions in all patients

- thereafter, a sulphonylurea, a glitazone and/or insulin can be added in any order according to the patient’s individual need and preferences.

- However, the algorithm does permit some therapy combinations that are off-label or even contraindicated in some countries, e.g. a glitazone in combination with insulin.

Eye care and erectile dysfunction

Annual screening for sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy should be performed in everybody with diabetes. Hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia are risk factors for sight-threatening retinopathy as well as for CVD and should be treated aggressively.10 Erectile dysfunction is a marker of both vasculopathy and neuropathy in diabetes and is strongly associated with CVD.11

Foot care

Diabetic foot disease is associated with both microvascular and macrovascular complications. Annual screening examination is a mandatory component of most diabetes care programmes. Many of the risk factors for CVD and diabetic foot disease are similar and an aggressive preventive approach to the former could potentially reduce the burden of the latter.12

Guardian drugs for cardiovascular prevention

JBS 2 recommends aspirin 75 mg daily for people with diabetes who:

- have established atherosclerotic disease

- are aged ≥ 50 years, or who are younger but have had diabetes for more than 10 years, or who are receiving treatment for hypertension.

As we have seen, statins are recommended for almost everybody with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, including all those aged 40 or more. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may have a special role in preventing diabetes complications.13 Whether or not all the claims made for these drugs are well-founded, they are effective and well-tolerated antihypertensive agents and appropriate for first-line use in people with diabetes. If microalbuminuria or proteinuria is present angiotensin receptor blockers reduce progression to worsening nephropathy, end-stage renal failure and death.14,15

A multi-factorial intervention in diabetes care

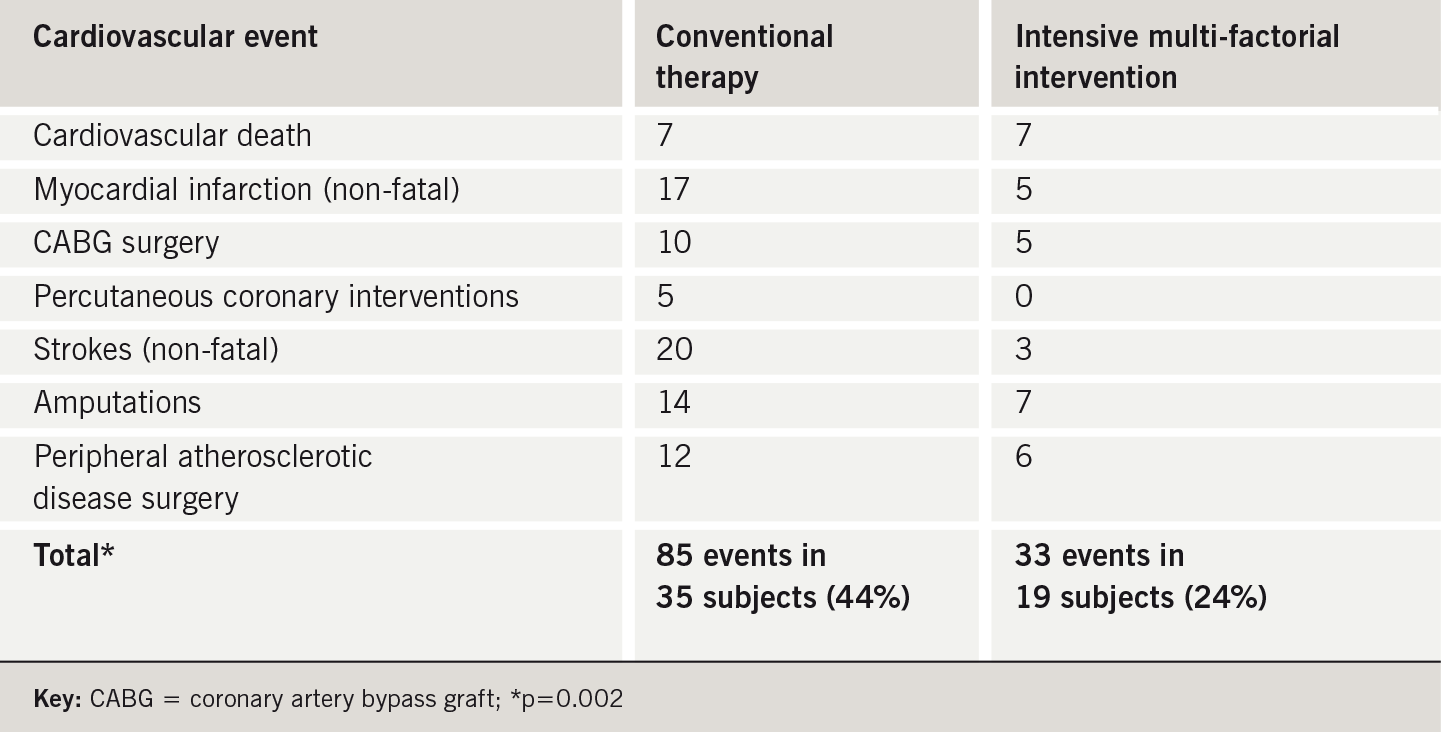

Many studies have assessed the effect of a single intervention on CVD outcomes in diabetes subjects. The Steno-2 study provided striking evidence of the benefits resulting from intensive target-driven multi-factorial intervention.16 One hundred and sixty patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria were randomised to receive either conventional treatment according to Danish national guidelines or aggressive intervention targeting all risk factors.

In the intensive-treatment group, CVD, nephropathy, retinopathy and autonomic neuropathy were all reduced by around 50%. There were 85 cardiovascular events in 35 subjects (44%) in the conventional therapy group but only 33 events in 19 subjects (24%) in those receiving intensive treatment (table 1). This is compelling evidence that intensive multi-factorial intervention in diabetes results in major CVD event reductions. Locally we have found that use of the Alphabet Strategy can help achieve the standards set by clinical trials in everyday practice.17

European guidelines

The recommendations for prevention of cardiovascular disease in JBS 2 have been broadly reflected in the joint ESC/EASD guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. They go further and discuss:

- impaired glucose homeostasis

- identification of subjects at high risk of CVD or diabetes

- management of CVD

- heart failure and diabetes

- arrhythmias: atrial fibrillation and sudden cardiac death

- hyperglycaemia and outcome of critical illness

- the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

In table 2, we have summarised both the JBS 2 and ESC/EASD guidelines in Alphabet Strategy format.

Conclusion

The debate about CVD risk reduction in diabetes often focuses on patients with type 2 diabetes. However, it should not be forgotten that people with type 1 diabetes have an even higher risk of premature CVD. Risk reduction must also be pursued aggressively in these individuals. The 10-year follow-up of the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study showed that blood pressure, lipid levels and concomitant peripheral vascular or renal disease were important risk factors for the prediction of CVD in type 1 diabetes.18 The JBS 2 recommendations therefore make no distinction between the interventions needed in type 1 and type 2 subjects: they are the same in both groups. The primary prevention of CVD in people with either kind of diabetes should be approached with the same urgency as secondary prevention in the general population.

Conflict of interest

JDL has received educational grants and conference fees from Astra Zeneca, Sankyo and Bristol-Myers Squibb. JRM and VP have received lecture fees and conference grants from all major pharmaceutical companies including Pfizer. SS: none declared.

Key messages

- Both the JBS 2 and the ESC/EASD guidelines endorse strict targets for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in individuals with diabetes

- CHD risk estimation is no longer recommended in subjects with diabetes: they are all at high risk and should be treated as such

- The target blood pressure has been reduced still further to 130/80 mmHg

- The majority of individuals with diabetes should receive statin therapy irrespective of baseline lipid profile

- The target for glucose lowering is normoglycaemia

- Low-dose aspirin is indicated for primary prevention of CVD in older patients and in those with diabetes of long duration

References

- Fisher M, Shaw K. Diabetes: a state of premature cardiovascular death. Practical Diabetes Int 2001;18:183–4.

- The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary. Eur Heart J 2007;28:88–136.

- British Cardiac Society, British Hypertension Society, Diabetes UK, HEART UK, Primary Care Cardiovascular Society, Stroke Association. JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart 2005;91(suppl 5):v1–52.

- Wood DA, Durrington P, Poulter N et al. Joint British recommendations on prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Heart 1998;80:S1–29.

- Department of Health. National service framework for coronary heart disease. Modern standards and service models. London: Department of Health, March 2000. Available from: http://www.doh.gov.uk/nsf/coronary.htm

- Patel V, Morrissey J. The alphabet strategy: the ABC of reducing diabetes complications. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2002;2:58–9.

- Beevers DG. The end of beta blockers for uncomplicated hypertension? Lancet 2005;366:1510–12.

- Deedwania P, Barter P, Carmena R et al. Reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with coronary heart disease and metabolic syndrome: analysis of the Treating to New Targets study. Lancet 2006;368:919–28.

- Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy. A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 2006;49:1711-21 and Diabetes Care 2006;29:1963–72.

- Patel V, Sailesh S, Panja S, Kohner E. Retinal perfusion pressure and pulse pressure: clinical parameters predicting progression to sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2001;1:80–7.

- Kirby M, Jackson G, Simonsen U. Endothelial dysfunction links erectile dysfunction to heart disease. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:225–9.

- Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Risk factors predicting lower extremity amputations in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1996;19:607–12.

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study investigators. Effect of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE study. Lancet 2000;355:253–9.

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001;345:861–9.

- Parving HH, Lehnert H, Brochner-Mortensen J et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in people with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:870–8.

- Gæde P, Pernille V, Larsen N et al. Multifactorial intervention with cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2003;348:383–93.

- Jaiveer P, Saraswathy J, Lee JD et al. The alphabet strategy: a tool to achieve clinical trial standards in routine practice? Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2003;3:410–13.

- Orchard TJ, Olson JC, Erbey JR et al. Insulin resistance-related factors, but not glycemia, predict coronary artery disease in type 1 diabetes: 10-year follow-up data from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1374–9.