The 2009 American College of Cardiology (ACC) meeting was held in Orlando, US, from March 29th–31st 2009. Highlights this year included the first major results from a clinical trial with the much talked about polypill, more good news for statins, to more encouraging results for drug-eluting stents in a real-world setting.

Polypill could cut cardiovascular risk by half

The strategy of giving a ‘polypill’, consisting of three antihypertensive drugs, a statin, and aspirin, to vast amounts of people who have not yet developed heart disease, could cut cardiovascular risk by half, according to the first major clinical trial of such an approach.

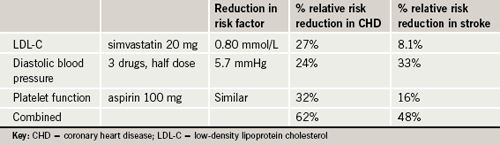

The Indian Polycap Study (TIPS), presented at the ACC meeting by Dr Salim Yusuf (McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada), included 2,053 patients aged 45–80 years without cardiovascular disease but with one risk factor (type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, smoker within the past five years, increased waist-to-hip ratio or abnormal lipids). They were randomised to receive the Polycap pill which included hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg, atenolol 50 mg, ramipril 5 mg, simvastatin 20 mg and aspirin 100 mg, or to eight other groups who received various components of the polypill either alone or in combination.

Results showed that the polypill lowered blood pressure similarly to the added effects of each of the three antihypertensive components, with no interference of aspirin. Beta-blockade and aspirin effectiveness were also similar with the polypill as with the individual components.

Adverse effects with the polypill were not increased compared with the other eight groups, and there appeared to be no drug-drug interactions. There was slightly less cholesterol lowering with the polypill than in patients who received simvastatin alone and the reduction in blood pressure was lower than projected from the antihypertensives included.

But Dr Yusuf said the results were encouraging and formed the first step towards the idea of taking a single pill to reduce multiple cardiovascular risk factors. “Before this study there were no data about whether it was even possible to put five ingredients into a single pill, in terms of feasibility, the bioavailability of different agents and possible interactions and we found that it works… this could revolutionise heart disease prevention as we know it,” he said.

Dr Yusuf and his colleagues estimate that the risk reductions seen with the polypill in this study would translate into a 62% reduction in coronary heart disease and 48% reduction in stroke (see table 1).

The TIPS study has also been published in The Lancet (Lancet 2009;373:1341–51) and in an accompanying editorial, Dr Christopher Cannon (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, US) says the polypill has “obvious appeal and vast implications for global health”, but he adds that larger outcome trials are needed to more fully assess the true feasibility of the strategy.

ACTIVE A: aspirin plus clopidogrel a reasonable alternative for AF patients unsuitable for warfarin

Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin for the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who are not able to take warfarin reduced major vascular events but increased bleeding risk in the ACTIVE A trial. The investigators said that for many patients, the benefit would outweigh the risk.

Warfarin is the treatment of choice for AF but many patients are not suited to its use as it has a high bleeding risk and requires regular monitoring and restrictions of lifestyle. Aspirin alone is currently used for these patients but it is not as effective as warfarin.

Presenting the results, Dr Stuart Connolly (McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) said: “We found that if you treated 1,000 patients over the course of three years by adding clopidogrel to aspirin, you would prevent 28 strokes, 17 of which would be fatal or disabling, and you would prevent six heart attacks. This would occur at a cost of 20 major haemorrhages,” he said.

“Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in many patients with AF, unsuitable for warfarin, will provide an overall benefit at an acceptable risk,” said co-principal investigator Dr Salim Yusuf (McMaster University). “When compared to aspirin alone, warfarin is more effective than clopidogrel plus aspirin against stroke in AF. However clopidogrel provides only about three-quarters of the benefit of warfarin over aspirin, but with only about three-quarters of the increased risk of major and intracranial haemorrhage,” he added.

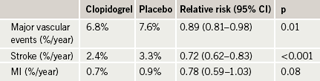

The ACTIVE A trial enrolled 7,554 patients with documented AF and at least one risk factor for stroke. All patients were treated with aspirin (75–100 mg/day, recommended) and randomised to receive either clopidogrel (75 mg/day) or matching placebo. The primary outcome was the composite of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), non-CNS systemic embolus or vascular death; major bleeding was a secondary safety outcome.

After a median follow-up of 3.6 years, the primary outcome (see table 1) was reduced by 11% with the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin. This reduction was driven by a 28% reduction in stroke. There was a trend towards a reduction in MI, but no reduction in vascular death and no reduction in non-CNS systemic embolism.

However, the rate of major bleeding was significantly increased with clopidogrel, and there was a trend towards increased fatal bleeding (table 2).

Novel device could replace warfarin for AF patients

A device implanted in the heart using minimally invasive techniques could replace warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF), results of the PROTECT AF trial suggest. The device is a fabric-covered expandable cage known as the Watchman, which blocks blood clots that typically form in the left atrial appendage (LAA), an out-pouching of the left atrium.

In the study, 707 patients were randomised to closure of the LAA with the WATCHMAN device followed by discontinuation of warfarin, or to long-term treatment with warfarin. 87% of patients receiving the device were able to stop warfarin therapy at day 45. By one year, 93% of patients were off warfarin permanently.

Results showed a trend towards a reduction in the primary end point – the combined rate of stroke (ischaemic and haemorrhagic) and cardiovascular death in the device group. This occurred in 3.4% of the device patients and 5% of the control patients (relative risk 0.68).

Although there were complications related to device implantation (mainly pericardial effusion), after implantation and discontinuation of warfarin therapy, complication rates were significantly lower with the device than with warfarin treatment.

“The take-home message is that although there are complications associated with implantation of the device, patients can avoid the need for chronic warfarin therapy, with all its attendant risks,” said lead investigator, Dr David Holmes (Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, Rochester, US).

Preload statins before PCI?

Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can benefit from additional loading of statin treatment, two new Italian studies suggest.

In one study, ARMYDA RECAPTURE, patients who were already on statin treatment had reduced event rates 30 days after PCI if they were given an extra 80 mg dose of atorvastatin 12 hours before PCI and another 40 mg dose immediately prior to the procedure.

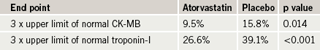

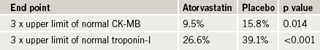

In the other study, NAPLES II, patients not on chronic statin therapy had a lower incidence of periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI) if they received an 80 mg loading dose of atorvastatin 24 hours before PCI.

In ARMYDA-RECAPTURE, 352 patients with stable angina or non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (ACS) who were already taking statins were randomised to the atorvastatin reload or to placebo. All patients were treated with atorvastatin 40 mg after PCI. At 30 days, the composite of cardiac death, MI or target vessel revascularisation (TVR) was significantly lower among patients reloaded with atorvastatin prior to PCI (3.4%) versus placebo (9.1%) (p=0.045). The benefit was driven by a large reduction in periprocedural MI.

Lead investigator, Dr Germano Di Sciascio (Campus Bio-Medico University, Rome, Italy) pointed out that most of the benefit was seen in patients with acute coronary syndrome, rather than those with stable angina. He suggested that if these results could be confirmed in larger studies, then statins may become another medication to be given to ACS patients on first medical contact, like aspirin or clopidogrel.

In NAPLES II, 668 statin-naive patients scheduled for elective PCI were randomised to atorvastatin 80 mg 24 hours pre-procedure or placebo. At 30 days, the atorvastatin group showed a significantly reduced risk of periprocedural MI as defined by elevations of CK-MB and cardiac troponin I (table 1).

Discussing these results, Dr Christopher Cannon (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, US) noted that a very early effect of high dose atorvastatin had also been seen in the PROVE-IT study, and that it was believed that anti-inflammatory effects of statins may be responsible for this benefit. He suggested that intensive statin treatment should be started immediately on hospital admission in ACS patients, the day before PCI if possible.

JUPITER: statins reduce risk of VTE as well

Another possible use for statins that can be added to their seemingly never-ending list of benefits, may be the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to new results from the JUPITER trial with rosuvastatin.

The reduction in VTE seen with rosuvastatin in this trial was similar to and independent of the reduction in cardiovascular events, which has previously been reported.

Presenting the new JUPITER results at the ACC meeting, Dr Robert Glynn (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, US) said: “VTE is a serious, sometimes fatal, event that is costly and inconvenient to treat. When patients and their doctors discuss initiation of statin therapy, prevention of VTE is an important additional consideration beyond proven benefits in the prevention of heart attack and stroke”.

JUPITER is the first randomised trial to prospectively investigate whether statin therapy can prevent VTE. The trial randomised 17,802 apparently healthy men and women to either rosuvastatin 20 mg/day or placebo. The median age of study participants was 66 years, and 38% were obese.

During follow-up, 34 participants in the rosuvastatin group and 60 in the placebo group developed symptomatic VTE, a 43% reduction (hazard ratio, 0.57; p = 0.007). Similar reductions in risk were observed in people who had certain triggers for VTE, including cancer or recent hospitalisation, surgery, or trauma, and in those who did not have any of these triggers. Risk reductions were seen for both deep vein thrombosis and for pulmonary embolism.

“Our findings require confirmation, but they have the potential to broaden our perspective on the treatment targets for statin therapy,” Dr Glynn said. “The clinical bottom line here is simple,” said co-investigator, Dr Paul Ridker (also from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital). “In addition to reducing risks of heart attack and stroke, we now have hard evidence that aggressive statin therapy reduces life-threatening blood clots in the veins. In contrast to drugs like warfarin and heparin, we got this benefit with no bleeding hazard at all, so the new data are an exciting advance for our patients.”

Low LDL and CRP best for reducing events

Another analysis of JUPITER has shown that healthy men and women who achieved the largest reductions in both low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and C-reactive protein (CRP) after starting statin therapy had the best reduction in risk of a future cardiovascular event. Presenting the data, Dr Paul Ridker suggested that clinicians should consider screening for CRP, in addition to LDL cholesterol when identifying patients at high risk for heart disease or monitoring the success of treatment among patients starting statin therapy. “Our data strongly confirms that statins reduce vascular risk by lowering both inflammation and cholesterol, and we found that achieving low levels of both matters for heart health,” he said.

In this analysis of 15,548 initially healthy men and women randomised to rosuvastatin 20 mg or placebo, the composite end point of MI, stroke, hospitalisation for unstable angina, arterial revascularisation, or cardiovascular death was reduced by 65% versus placebo in those receiving the statin who achieved target levels of LDL less than 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) and CRP less than 2 mg/L. This compared to 36% reduction among those treated with rosuvastatin who did not achieve one or both of these target levels.

Coronary artery calcium can help judge heart disease risk

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring can help predict who is most likely to have a cardiac event among those classified as ‘intermediate risk’, according to traditional risk factor assessment, a new study shows.

The Heinz Nixdorf Recall study found that the CAC score was a better predictor of cardiovascular disease than classic risk factors at predicting risk over five years. When the two sets of information were added together, predictive strength was better still. The findings were drawn from an observational study in a general population, roughly half of whom were women.

“Our results demonstrate that prediction of coronary events can be improved when calcium scoring is performed, especially in persons in the intermediate-risk category,” said Dr Raimund Erbel (University Clinic Essen, Germany). “This means that persons at intermediate risk with a high coronary calcium score should be recommended intensive lifestyle changes and maybe risk-modifying medication, while persons at intermediate risk with a low coronary calcium score have a more favourable prognosis.”

Coronary calcium levels are detectable long before other symptoms of coronary disease. The total coronary calcium burden is considered a measure of the extent of atherosclerotic disease. In addition, it is currently believed that a large amount of coronary calcium indicates a high likelihood of rupture-prone plaque somewhere in the coronary arteries. This may explain the link between the coronary calcium score and increased rates of cardiac events, he explained.

The study enrolled 4,487 patients without known coronary disease who were placed into risk categories on the basis of standard cardiovascular risk factors. Electron-beam CT was used to measure the coronary calcium score. Of the 4,137 study participants with complete follow-up data, 93 suffered cardiac death or non-fatal myocardial infarction, including 28 women. When coronary calcium scores in the highest quartile were compared to those in the lowest quartile, the relative risk of a cardiac event was 3.16 (p = 0.009) for women and 11.09 (p<0.0001) for men.

Researchers then developed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, to calculate the ability of a test to predict a clinical event, with a score of 1.0 being ideal. The area under the curve for the traditional risk categories was 0.667, compared with 0.740 for coronary calcium scoring and 0.754 for the combination.

“Calcium scoring has now been validated and reached a place in preventive cardiology,” Dr Erbel said, adding that they now plan to follow patients for an additional five years to analyse 10-year risk prediction capability of coronary calcium scoring and other factors.

ABOARD: immediate cath no better than next day for NSTE-ACS

Immediate catheterisation was no better than next day intervention in the ABOARD study of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) patients.

Presenting the study, Dr Giles Montalescot (Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France) noted that the issue of early versus late intervention in NSTE-ACS patients had been thoroughly investigated previously but that ‘early’ was generally considered to be from three to 96 hours and ‘late’ was generally very late (50 to 1464 hours).

The ABOARD study was different in that it was conducted to look at whether there was an advantage of immediate intervention compared to next-day intervention in 352 patients with moderate to high-risk NSTE-ACS. Triple antiplatelet therapy was used in both study groups. The median time from randomisation to angiography was 1.2 hours in the immediate group, and 20.5 hours in the delayed group.

Results showed no difference in peak troponin I levels during hospitalisation (the primary end point) and there was also no difference in the key secondary end point of death, new myocardial infarction (CK-MB) or urgent revascularisation at one month, or in other efficacy or safety end points. But the immediate catheterisation group did have a shorter hospital stay by one day.

Dr Montalescot concluded: “Our study confirms that there is no optimal timing for catheterisation in the first 24 hours of presentation for NSTE-ACS. He added that immediate catheterisation/PCI with strong antiplatelet therapy is an acceptable strategy, which may be particularly useful in high volume centres with a rapid turnover and an activated cath lab when the patient presents.

Early heparin and clopidogrel key to reducing stent thrombosis in STEMI

Inadequate early antithrombin and antiplatelet therapy is a strong driver of early stent thrombosis in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and cigarette smoking is one of strongest drivers of late stent thrombosis, according to new data from the HORIZONS AMI trial.

Presenting the latest results from this study, Dr George Dangas (Columbia University Medical Center, New York, US) said that giving a heparin bolus and 600 mg of clopidogrel to all STEMI patients either in the ambulance or as soon as they arrive in the emergency room and strong warnings to give-up smoking could make a big impact on stent thrombosis rates.

The HORIZONS AMI trial was primarily a comparison of bivalirudin versus heparin plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor in 3,602 STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. The main results showed better outcomes with bivalirudin, with less major bleeding, comparable rates of ischaemia and improved survival.

The current analysis of stent thrombosis was based on the 3,203 patients who received a stent. There were 107 cases of definite or probable stent thrombosis (3.3%) by one year, 0.9% occurring in the first 24 hours (acute), 1.6% between one and 30 days (sub-acute), and 1% between one month and one year (late).

Dr Dangas noted that patients given early non-randomised heparin before entering the trial had significantly lower rates of stent thrombosis within the first 24 hours regardless of the treatment group to which they were assigned. A 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel also appeared to be important in reducing stent thrombosis, particularly sub-acute stent thrombosis in the bivalirudin group.

Other factors that affected acute and subacute stent thrombosis in HORIZONS AMI were vessel flow, lesion characteristics and number and length of stents, while patient related factors including cigarette smoking were predictors of late stent thrombosis. The type of stent implanted (drug eluting or bare metal) did not affect the risk of stent thrombosis during any time interval up to one year.

‘Real-world’ study finds drug-eluting stents safe

The largest-ever study to evaluate stenting in ‘real-world’ patients has found that drug-eluting stents are more effective than bare-metal stents at protecting patients against cardiovascular events, and are equally safe. The study found that during three years of follow-up, drug-eluting stents significantly reduced the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), death and further revascularisation procedures when compared to bare-metal stents, while provoking no increased risk of stroke or major bleeding.

“The biggest take home message of our study is: ‘Drug-eluting stents are safe’ ”, said Dr Pamela Douglas (Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, US). For the study, researchers analysed data from the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry on patients over the age of 65 who had undergone a stenting procedure from 2004 to 2006. Of these, 217,675 were treated with drug-eluting stents and 45,025 were treated with bare-metal stents. Follow-up information for each patient was obtained from Medicare claims data.

After adjusting for 102 patient characteristics such as sex, age and co-existing medical conditions, results showed that patients who received drug-eluting stents had significantly lower rates of death (hazard ratio 0.75), non-fatal MI (HR 0.76) and repeat heart procedures (HR 0.91) when compared to patients who received bare-metal stents. In addition, there were essentially no differences in rates of stroke (HR 0.96) or major bleeding (HR 0.91).

ZEST: which drug-eluting stent?

The new zotarolimus-eluting stent (Endeavor®) gave similar results to the sirolimus-eluting stent (Cypher®), but the new paclitaxel-eluting stent (Taxus Liberte®) did not look so good in a Korean ‘real-world’ trial.

In the ZEST trial, 2,645 patients with coronary artery disease were randomised to receive sirolimus-, paclitaxel- or zotarolimus-eluting stents. Results at one year showed no difference for the primary end point of death, myocardial infarction or ischaemic driven target vessel revascularisation, between the zotarolimus and sirolimus stents, but the paclitaxel stent showed a higher rate (table 1).

Discussant of the trial, Dr Stephan Windecker (University Hospital, Berne, Switzerland) said the study showed that “Endeavor® is less effective than Cypher®, but at least as effective as Taxus®.” He added that longer term follow-up was needed to better judge stent thrombosis rates.

REVERSE: CRT benefits mild heart failure patients after two years

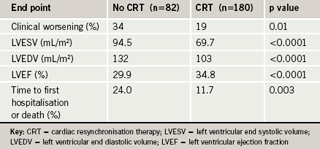

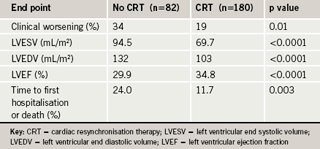

Latest (two-year) results from the REVERSE trial suggest that cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) does benefit patients with mild heart failure who also have poor left ventricular function and broad QRS.

Reported last year, the one-year results did not show a significant difference in the primary end point – a clinical composite of all-cause mortality, heart failure hospitalisation, crossover due to worsening heart failure, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and the patient global assessment. However, CRT did appear to improve left ventricular ejection fractions.

The two–year results, however, showed that patients receiving CRT had both reduced ventricular volumes and less clinical worsening than patients not receiving CRT (see table 1). But there was no change in the functional parameters, such as quality of life, exercise test, and NYHA class.

Discussant of the study, Dr Richard Page (University of Washington, Seattle, US) said he had difficulty reconciling the lack of functional benefit with the modification of disease progression and reverse remodelling effect, and this, as well as the cost and complications associated with the device would have to be considered carefully before recommending use in mild congestive heart failure (CHF) patients. Larger trials of CRT in mild CHF patients are ongoing.