Clinical guidelines are vital to improving patient outcomes by helping reduce practice variation, raising care standards, improving efficiency and maximising resource utilisation. To investigate the implementation/local adaptation of national guidance and approaches to post-myocardial infarction (MI) care across the UK, an assessment of the availability and implementation of local post-MI guidelines in England among primary care trusts (PCTs) and cardiac networks (CNs) was conducted. Secondly, a survey of UK GPs and nurses (n=1,003) was performed to establish awareness of guidelines and to investigate whether there are regional variations in the management of post-MI patients.

Fifteen post-MI clinical guidelines were obtained (PCTs – 8; CNs – 7) and analysed according to the following topics: lifestyle modifications, cardiac rehabilitation, therapeutic intervention, therapeutic targets and communication between primary and secondary care. Considerable regional variation in the recommendations were found – particularly with regard to therapeutic interventions and targets – with differing targets for blood pressure and cholesterol management. This was mirrored in the survey results, which also showed significant inconsistencies in clinical practice as reported by UK healthcare practitioners.

In conclusion, little consistency in the availability and content of local post-MI clinical guidelines, coupled with disparities in national guidelines, suggest the need for national post-MI guidance, built on existing evidence, endorsed by clinicians and patients, which will promote optimal care and reduce practice variation.

Introduction

Clinical guidelines are becoming an increasingly important component of clinical practice across Europe as governments, while facing spiralling healthcare costs, still have to maintain an overriding commitment to their citizens to provide best possible medical care. As systematically developed statements that incorporate research evidence and expert consensus views, clinical guidelines represent a means of assisting practitioners and patients on decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific circumstances.1 Adherence to clinical guidelines, thus, will help to reduce practice variation, raise standards of care, improve efficiency in clinical management, standardise healthcare resource utilisation and ultimately improve health outcomes for the population.2,3 Clinical guidelines also serve to inform individuals and patient groups about the care that they can expect to receive with respect to certain illnesses. In our era of freely available information and increasingly sophisticated internet-based discussion, it is likely that guidelines will be used to benchmark and monitor clinical performance, at least informally.

Nowhere is the desire to improve clinical effectiveness greater than in the management of coronary heart disease (CHD). CHD is a common condition, a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK population and a significant burden to NHS resources, costing an estimated £3.2 billion in 2006.4

In a bid to understand the extent to which national guidance on CHD is being locally adapted (in the form of local post-myocardial infarction [MI] guidelines) and implemented, as well as to gauge regional variations in post-MI care, we undertook a qualitative research project that consisted of two parts. First, a survey of primary care trusts (PCTs) and cardiac networks (CNs) in England was undertaken to ascertain the existence and availability of current post-MI guidelines and explore any regional variations present. Second, a survey of general practitioners (GPs) and nurses was conducted, to establish the level of awareness of both national and local post-MI clinical guidance among primary healthcare professionals (HCPs) across the UK, and identify whether there are any reported variations in the management of post-MI patients. This latter phase of research included HCPs in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and allowed for comparisons to be made between the approach taken in England and that in the devolved nations, in addition to providing greater insight into the management of post-MI care across the whole of the UK.

Methods

Stage 1: Internet search and telephone interviews with cardiac networks in England

An internet search was carried out to gauge the availability of post-MI clinical guidelines from PCTs and CNs online. After an initial broad search using relevant terms, the top four PCTs by population in each Strategic Health Authority (SHA) region were identified and their websites searched for post-MI clinical guidelines. A similar strategy was employed for the 28 CNs in England, of which 25 had websites. Key patient group websites were also searched to identify what information is available for patients regarding their ongoing post-MI care and treatment.

After the internet search, efforts were made to contact all CNs directly. Initial contact was made via telephone or email. A call script was developed to ensure consistency in obtaining information. Key topics included:

- The existence of a post-MI clinical guideline

- How the guideline is made available to HCPs

- Whether adherence to the guideline is monitored

- The existence of information material for post-MI patients.

The guidelines identified were analysed for five main areas as pre-specified by the Steering Committee: lifestyle modifications, cardiac rehabilitation, therapeutic intervention, clinical management targets and communication between primary and secondary care. These were deemed essential topics for inclusion in a post-MI guideline.

Stage 2: Primary care survey of GPs and nurses across the UK

In the second stage, a survey of GPs and nurses across the UK was conducted to establish the wider national picture. A total of 802 GPs and 201 practice nurses participated, with recruitment weighted to include proportional numbers of practitioners from each SHA region in England as well as Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The HCPs completed an online survey of 61 questions to establish awareness of locally developed post-MI clinical guidelines and use of these versus national guidelines, as well as to identify any variation in clinical practice within the five key areas highlighted previously.

Results

Guideline research in England

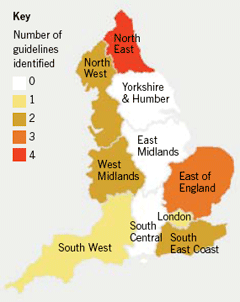

A total of 15 post-MI clinical guidelines within England were identified from the internet search and subsequent CN interviews (figure 1). Interviews were conducted with 18 out of the 28 CNs. Where interviews could not be conducted it was due to lack of availability of correct contact details, or inability to identify the appropriate individual to speak to.

The 15 guidelines obtained from PCTs (n=8) and CNs (n=7) were reviewed and the key findings, grouped according to the pre-specified areas of guidance and linked with results from the primary care survey, are summarised in table 1.

Cardiac network interviews in England

Information on dissemination and implementation of guidelines was also obtained – the 18 CNs with post-MI guidelines had a variety of distribution methods. One distributed guidance only on request from HCPs, while others sent it in hard copy or electronic format directly to each practice or individual GP in the area. Another network embedded their guidance on the computer operating systems of GPs. Only one network offered a training event to raise awareness and understanding of their guidance. CNs without specific post-MI guidance tended to promote awareness of national guidance; most commonly the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline on secondary prevention of MI.

There was very little consistency between CNs with regards to ensuring implementation of guidance; most did not have specific programmes for implementation.

CNs were also asked about the existence of materials for post-MI patients. Only two out of the 18 CNs had developed specific patient materials, which included treatment cards and glossaries explaining medical terminology. These were distributed by the multi-disciplinary teams at tertiary centres. About half of the networks reported that they consult patients through forums or by inviting patient representatives to participate in their guideline development groups. Most CNs did not feel that it was their role to develop and distribute post-MI patient material, with over half expressing a view that the British Heart Foundation provides comprehensive patient information.

UK primary care survey5

Development of post-MI clinical guidelines

Results from the primary care survey suggest that local post-MI guidelines were most likely to be developed by local hospitals (49%) and PCTs (46%) with only 21% of respondents attributing the development of local guidance to CNs. Although about two-thirds of UK HCPs were aware of local post-MI guidance in their area, the results of the survey showed that NICE clinical guidance was, nevertheless, preferentially followed by the majority (60%) of HCPs in the UK; 65% in England in contrast to 78% in Wales and 44% in Northern Ireland. In Scotland, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidance was the most closely followed (55%), with only 15% of HCPs in Scotland following NICE guidance for post-MI care.

Definitions of the patient population

There was very little consensus among primary HCPs on the definition of the patient population for which the guidelines were intended. Twenty-six per cent of respondents looked to NICE guidance for a definition of post-MI, 25% followed definitions found within the local PCT formulary, but 23% admitted to not knowing what defines a post-MI patient.

Implementation of post-MI clinical guidance

There appeared to be different methods in clinical guideline implementation in the different nations. In England, monitoring adherence to local post-MI clinical guidelines was largely undertaken by audits, which were either practice-led (49%) or PCT-led (45%). On the other hand, respondents in Scotland and Wales had softer influences on guideline adherence; 58% of Scottish HCPs were influenced by local commitments to follow local guidance and Welsh HCPs felt that agreements with secondary care (60%) were important to encourage adherence. Most of the respondents from Northern Ireland (67%) said they were generally influenced by peer pressure (please note small base size in Wales and Northern Ireland). Where applicable, 39% of UK respondents felt that local post-MI clinical guideline implementation was monitored through the achievement of Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) targets for the relevant indicators.

Discussion

Results from this study suggest that there is considerable variation in the availability, recommendations and implementation of post-MI clinical guidelines in the UK, both between and within regions. One important finding, which may underpin the reasons for this variation, is the lack of consistency in the organisation that develops and implements post-MI clinical guidelines. In some areas, guidelines are developed and disseminated by local hospitals, whereas in other areas, PCTs undertake this responsibility. CNs are least likely to develop local post-MI guidance with a significant number stating that this responsibility should be devolved to PCTs.

In England, CNs appear to have varying influence among nurses and GPs, who more commonly use guidance recommended by PCTs (47%) and/or their own practice (46%) compared to CN-developed guidance (24%). However, this level of influence varied across regions, with more respondents from the East of England (38%) and the North East (37%) indicating they would follow guidelines developed by CNs.

The differences in the recommendations of post-MI clinical guidance, with particular regard to therapeutic interventions and targets, may not be surprising given that there are some inconsistencies between national clinical guidelines for secondary MI prevention. For example, the cholesterol treatment targets for post-MI patients range from total cholesterol (TC) <5 mmol/L (National Service Framework [NSF] for CHD 2000,6SIGN7 and QOF8) to TC <4 mmol/L and/or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) <2 mmol/L (Joint British Societies [JBS-2]9 and NICE10). Alignment to these differing recommendations may well be a key factor resulting in the variation seen in this study. In addition, few CNs in England had the means of ensuring their guidelines were updated regularly – potentially a further reason for inconsistencies. Finally, the post-MI clinical guidance obtained from PCTs and CNs in this study suggest that there may be differences in defining the patient population for whom the guideline is intended. For example, one network specified guidance for non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI) patients, whereas another distinguished between acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients and MI patients. This may be a reason for the differing opinions of UK HCPs on post-MI definitions leading to variations in clinical practice.

Interviews with CNs revealed that most did not have specific programmes for guideline implementation. This, coupled with the finding that there is substantial variation in the recommendations of both national and local post-MI clinical guidance, may explain why clinical management of such patients varied considerably. For example, the NICE lipid modification clinical guideline10 recommends the use of a higher-intensity statin (defined as a statin used in doses that produce greater cholesterol lowering than simvastatin 40 mg) without delay in patients with ACS. However, 44% of HCPs in England and 51% in Wales indicated that simvastatin 40 mg would be their first-choice therapy option in this group. It would appear that although 65% of respondents in England and 78% of respondents in Wales reported that they chose to follow NICE guidance, actual clinical practice may differ. Another key driver of clinical practice is the QOF – 28% of UK respondents indicated that this would most commonly influence treatment selection. QOF provides a monitoring framework for adherence to certain aspects of secondary prevention, incentivised by payments linked to achieving percentages of target figures. Although general practices achieve extremely high percentages in this annual audit, the targets for treatment are benchmarked at minimum audit standards and many important aspects of follow-up care are not monitored. There are concerns that this may distort the provision of care and contribute to the ongoing variation in clinical practice in this high-risk patient population.

It is important to note that this is a qualitative study and, while it has generated some very interesting conclusions, it has some limitations. The number of post-MI clinical guidelines identified may have been limited by the following factors. First, some guidelines may have been located on websites that were password protected and, therefore, not publicly available. Second, the initial research phase focused entirely on England and prioritised only the top four PCTs by population in each SHA; relevant guidelines may well have been missed. Third, our initial assumption that most post-MI clinical guidance is developed by PCTs and CNs may have been wrong as 49% of respondents acknowledged that guidelines were developed locally by hospitals. We were not able to assess whether guidance developed by hospitals focuses solely on pathways of care in the immediate acute phase post-MI or whether it extends to guidance on continuing secondary prevention post-MI. Finally, we were unable to conduct interviews, and thereby identify any relevant clinical guidelines, with 10 out of the 28 CNs.

Conclusion

The findings from this qualitative study suggest that there is little consistency in the availability and content of local post-MI clinical guidance. This may contribute to the significant variation in clinical practice, as reported by GPs and nurses, when managing post-MI patients. The availability of national clinical guidance for this patient population does not appear to address the issue of practice variation – although the majority of respondents indicated that they follow NICE clinical guidance, this did not always translate into actual clinical practice. These findings indicate that, in some areas, patient care may not be optimal.

Ultimately, the success of a clinical guideline is measured by its ability to promote evidence-based best clinical care and improve clinical outcomes by reducing practice variation. Guidelines should be built on existing evidence and endorsed by both clinicians and patients.

In a bid to minimise this significant variation in practice across the UK and promote improved and consistent patient care, HEART UK, the Primary Care Cardiovascular Society (PCCS) and Pfizer have come together in a novel three-way partnership to support the development of new guidance to help clinicians manage post-MI patients. Although facilitated by financial support from Pfizer, each of the three organisations contribute equally and enjoy parity in decision-making, bringing together the right mix of individual perspectives, skills and key experts in the field to collaboratively drive this project. The guidance, which will be supported by the current evidence base, is intended to represent optimal care and treatment with both HCP and patient components recognising the crucial role of the patient and their families in the achievement of best clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The content of this manuscript was developed by the authors on behalf of the Follow Your Heart Steering Committee, made up of members from HEART UK, PCCS and Pfizer.

Conflict of interest

At the time of this research, SO was an employee of Pfizer. DM and JM both received funding for their contribution to the Follow Your Heart project, which is being financially supported by Pfizer.

Key messages

- Clinical guidelines are vital to improving patient outcomes by helping reduce practice variation, raising care standards, improving efficiency and maximising resource utilisation

- There is considerable variation in the availability, recommendations and implementation of post-myocardial infarction (MI) clinical guidelines in the UK

- Although healthcare professionals refer to national clinical guidelines as a key driver influencing patient care, actual clinical practice often differs

- There is a need for national post-MI guidance, built on existing evidence, endorsed by clinicians and patients, which will promote optimum care and reduce practice variation

References

- Field MJ, Lohr KN (eds). Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990.

- Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 1993;342: 1317–22.

- Bahtsevani C, Uden G, Willman A. Outcomes of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2004;20:427–33.

- British Heart Foundation. Healthcare and economic costs of CVD and CHD. Available from: http://www.heartstats.org/datapage.asp?id=101 [Accessed April 2009].

- Post Myocardial Infarction Care in Practice. Online survey conducted by medeConnect Healthcare Insight (part of the Doctors.net.uk group), March 2009.

- Department of Health. National service framework for coronary heart disease, Chapter 2: national standards and service models, standards 3 and 4 – preventing CHD in high risk patients. London: DoH, March 2000; pp. 23–24.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN CG 97. Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Edinburgh: SIGN, February 2007. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign97.pdf [Accessed April 2009].

- Quality and Outcomes Framework: Guidance for GMS contract 2009/10, Section 2 Clinical Indicators, Secondary prevention of CHD. March 2009; pp. 26-31.

- Joint British Societies. JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart 2005;91(Suppl V):v1–v52.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE CG67. Lipid modification clinical guidelines. London: NICE, 2008. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG67NICEguideline.pdf [Accessed April 2009].