The highlight of this year’s SHARP Annual Scientific Meeting, held at Dunkeld House, Perthshire, on 24th–25th November 2011, was a mini symposium held in conjunction with the British Hypertension Society (BHS). Dr Alan Begg reports.

Every day practice

This year’s meeting examined the importance of both pulse and blood pressure in everyday clinical practice. Professor Tom McDonald (University of Dundee), Vice President of the BHS, welcomed delegates to the symposium on blood pressure and vascular disease, held in conjunction with the BHS. Current interest in the subject results from the publication last year of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline 127 on the clinical management of primary hypertension in adults, and its recommended approach to hypertension diagnosis and blood pressure management.1

The first speaker, Professor Mark Caulfield (William Harvey Research Institute, London) was introduced by the symposium chairman, Dr Terry McCormack, a member of the executive committee of the BHS, and also of the NICE guideline development group. Professor Caulfield outlined how a systemic review of clinical evidence and cost effectiveness was merged into the evidence-based recommendations of the guideline.1 In the UK, roughly 25% of adults have hypertension, which accounts for 12% of patient consultations in primary care. The risk of hypertension cannot be over-emphasised, he said, with a 2 mmHg increase in blood pressure equating to a 7% increase in coronary heart disease (CHD) risk and a 10% increase in stroke risk, with a considerable potential cost to society. He pointed out that the new NICE guideline covers adults with primary hypertension, with or without pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), although patients with diabetes were not included. With the trend towards using automated recording devices, he emphasised the importance of checking the pulse to see if it is regular before deciding whether to use such a device or check blood pressure manually.

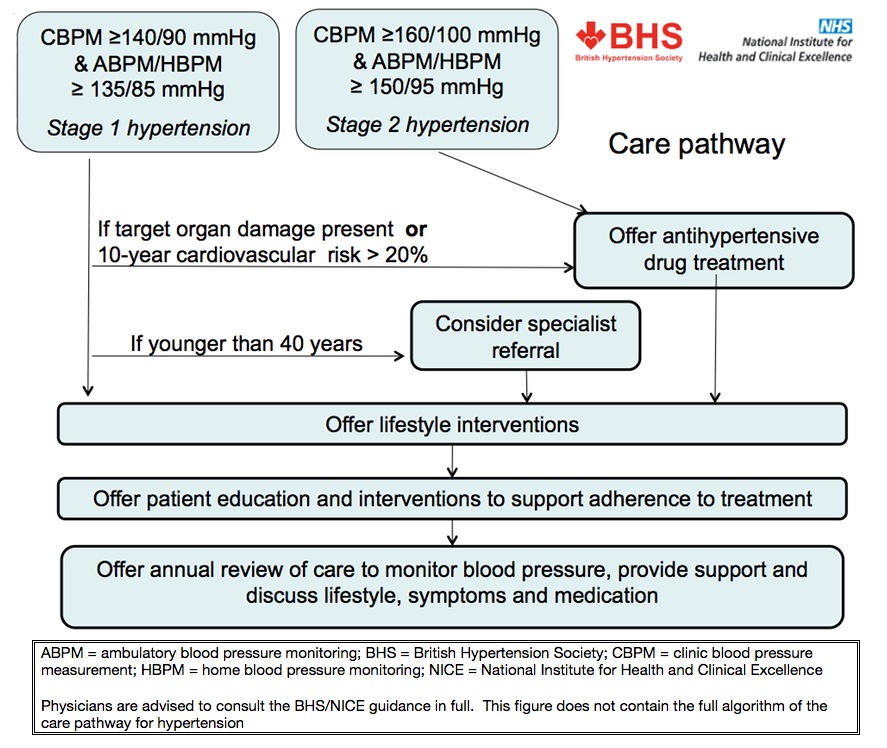

It is now recommended that confirmation of the diagnosis should be based on the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM), with ABPM being seen as the gold standard in predicting long-term prognosis. Lifestyle change remains important as does patient education, especially in order to improve adherence to medication. Professor Caulfield’s ‘take home message’ was to follow the care pathway published by the BHS and NICE, as the ideal approach to a patient with primary hypertension (figure 1). He described the ‘white coat effect’ as a discrepancy of more than 20/10 mmHg between clinic and average daytime ABPM and/or average HBPM blood pressure measurements at the time of diagnosis.

Summarising antihypertensive treatment, the original AB/CD rules have now evolved to include the use of a renin-blocking drug (A drug) in those 55 years, and to black people of African or Caribbean family origin of any age. On balance, he felt there were advantages of calcium channel blockers over diuretics in stroke outcomes, with less new onset diabetes than with diuretics. Patients over the age of 80, he said, should be treated in the same way, but their co-morbidities need to be taken into account. The BHS pathway studies may give us a future better understanding of how we should manage resistant hypertension,2 but he was in no doubt that the key message, in terms of cost-effectiveness, was that treating hypertension was now cheaper than doing nothing.

Every day treatment strategies

Looking at treatment strategies recommended for the management of blood pressure, Professor Maurice Brown (University of Cambridge) pointed out that the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration showed the benefit of antihypertensive treatment was proportionate to the reduction in blood pressure,3 and that variability in blood pressure has a poor prognosis even with good control of mean blood pressure. Interestingly, in the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study population, the risk of death was greater with a given increase in home or ambulatory blood pressure, but these values were not prognostically superior to clinic values.4 He outlined the Rotation Studies and the realisation that in patients aged under 50 years old, AB drugs were almost twice as effective in lowering blood pressure as CD drugs.5

This led to the description of two types of hypertension:

- type 1 hypertension with high renin vasoconstriction effect, which we can treat with AB drugs

- type 2 low renin sodium dependant hypertension, for which CD drugs would be more appropriate.6

The NICE recommendation for diuretic therapy is a thiazide-like diuretic such as chlortalidone 12.5 mg daily, a formulation not available in the UK, or indapamide 1.5 mg modified release daily or 2.5 mgs daily, with its only outcome trial in hypertension being too small to achieve its primary outcome benefit.

For those patients uncontrolled on three drugs, he proposed measuring the serum renin:

- if high, add in a beta blocker (B drug)

- if normal, an alpha blocker should be used

- if low, change either the dose or choice of diuretic. Consideration should also be given to adding spironolactone or substitution with co-amilozide.7

Professor Brown felt that all blood pressure could be reduced by eliminating enough sodium and by preventing renin-angiotensin system compensation; the commonest cause of resistant hypertension, he thought, may be due to sodium retention in part due to the use of low-dose thiazides. His final point was that the commonest curable cause of hypertension is small, curable Conn’s adenomas, which are more frequent than realised.

Every day measurement

Is the significant increase in the size of the guidelines over the years reflected in their quality, asked Professor Paul Padfield (Edinburgh University)? Clinic systolic blood pressure readings, he pointed out, are often not reproducible with a large degree of variation. Readings can be reduced if HBPM is used. ABPM is a better predictor of cardiovascular death than clinic blood pressure readings, although patients may not prefer this. He felt clinic blood pressure readings should be used to monitor response to treatment, although ABPM or HBPM could be used as an adjunct to clinic readings if there was felt to be a ‘white coat effect’.

He outlined the benefits of a centrally organised ABPM service, with use of validated machines and standardised reporting and advice. The Scottish experience was that specialist advice from this service ‘not to treat’ was followed in 90% of cases, while advice ‘to treat’ was followed in 75% of cases. He outlined the Health Impact of Telemetry Enabled Self Monitoring (HITS) study, in which 200 patients received telemetry supported self monitoring compared with 201 patients who received normal care.8 Telemetry was shown to be more effective than usual care (p=0.0002), and the effect appeared to be mainly through the intensification of drug therapy rather than lifestyle changes. He was of the opinion that if HBPM is shown to be an acceptable alternative to ABPM then it is likely to become the norm, and that the future will be out-of-office blood pressure monitoring for all.

Appropriate measurement of blood pressure was continued in the workshops, with Mrs Alison Hume, Lead Specialist Nurse for the Hearty Lives Dundee programme, demonstrating how to use the equipment required for ABPM in clinical practice. She pointed out the importance of being familiar with the equipment, and aware of the calibration procedures for the device being used. Other important points were instructing the patient to keep the arm still during measurement, and asking them to keep a diary of activities and symptoms during the recording period. In the workshop discussion it was clear that ABPM is still seen as a specialist investigation, and not fully accepted as something that should be delivered in general practice, despite the comment from Dr McCormack earlier that NICE intended general practice to play the lead role in ABPM. It was felt that there was still a lot of work to be done to make sure that healthcare professionals were familiar with the tracings and interpreting the results. In addition to the debate about the benefits of ABPM, there were concerns about the implications for training, the purchase of expensive equipment, and supporting the software.

New development in other areas

Another session at the meeting considered an irregular heart rhythm in the context of the newer anticoagulant agents for reducing stroke risk in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. In the panel discussion most of the interest was around the identification of patients currently taking warfarin who would benefit from the newer oral anticoagulant agents, and whether in the light of the Scottish Consensus statement,9 drug budgets would allow their use in preference to warfarin.

Dr Shahid Junego addressed the problem of whether heart rate should be seen as a therapeutic target. He outlined epidemiological studies, which identified an association between heart rate and cardiovascular mortality in the general population, and other studies, which showed the poor prognostic outcomes in patients with an increased heart rate. Data were presented which showed that those with a high resting heart rate had a lower survival probability in terms of all-cause mortality, and also that hypertensive patients with higher resting heart rates have an increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and sudden death. Patients with heart disease and high resting heart rates have a lower survival probability, and the greater the heart rate-reducing effect of treatment, the lower the likelihood of an ischaemic event, the data showed.

Dr Junego also pointed out that, in heart failure trials, treatments that increased heart rate tended to increase mortality, and treatments that reduced heart rate tended to improve mortality. He thought a target heart rate should be considered with beta blockers or other agents in the management of patients with stable angina of between 55 and 60 beats/minute, and aim when appropriate for a heart rate of <50 beats/minute in severe angina.

A final conclusion from a very successful meeting was the realisation that, in the context of the NICE hypertension guidance, we may have now reached a situation where the guidelines are driving the need for the evidence.

Dr Alan Begg

GPwSI in Cardiology and Honorary Senior Lecturer

Townhead, Links Health Centre, Montrose, Scotland

(alanbegg@nhs.net)

References

1. NICE. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. NICE clinical guideline 127. Available from http://publications.nice.org.uk/hypertension-cg127

2. Prevention And Treatment of resistant Hypertension With Algorithm guided therapY (PATHWAY) studies. BHS Research Network. Available from: http://www.bhsoc.org/clinical_research.stm

3. Turnbull F. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Lancet 2003;362:1527–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39548.738368.BE

4. Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, Mancia G. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation 2005;111:1777–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000160923.04524.5B

5. Dickerson JE, Hingorani AD, Ashby MJ, Palmer CR, Brown MJ. Optimisation of antihypertensive treatment by crossover rotation of four major classes. Lancet 1999;353:2008–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07614-4

6. Brown MJ. Renin: friend or foe? Heart 2007;93:1026–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2006.107706

7. Brown MJ. The choice of diuretic in hypertension: saving the baby from the bathwater. Heart 2011;97:1547–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300710

8. Dr Janet Hanley. The impact of a telemetric hypertension monitoring service (randomised controlled trial with nested qualitative study). Telescot 2012. Available from: http://www.telescot.org/hypertension.html

9. Health Improvement Scotland. Consensus statement for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in adult patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. NHS Scotland, 2011. Available from: http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/default.aspx?page=13900