Demographics

The sample size was 261, constituting a 35% response rate (denominator: 745 trainees enrolled in cardiology with the Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board [JRCPTB]). Of respondents, 21% were female, though still a small proportion, this is the highest in eight years (for comparison, 13% female in 2004). Of the sample, 44% described themselves as white: white British (41%) or other white (3%). This continues a trend towards greater ethnic diversity. An increasing proportion of trainees (32%) originate in the Indian subcontinent (India 23%, Pakistan 7%, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh 1% each). The total in 2004 was 19%. The median age is 33 (range 27–44) years. Finally, 78% of trainees trained in the UK and 22% overseas.

Training intentions

A total of 51% of trainees are currently intending to dual accredit in cardiology and general medicine. This continues a downward trend since the first survey (2004: 89%, 2005: 75%, 2007: 68% intending to dual accredit). This reflects a decreasing number of consultant cardiologists on acute general medicine rotas.

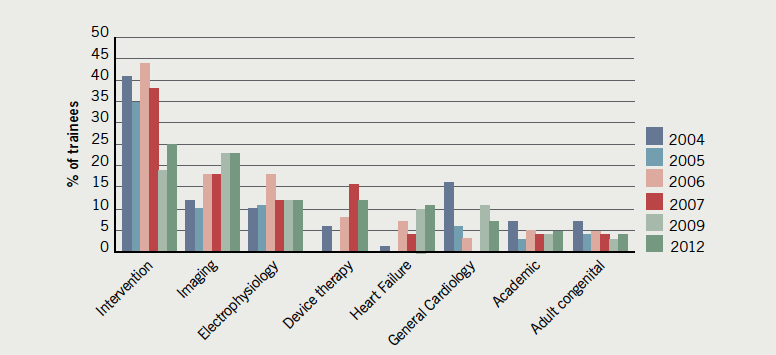

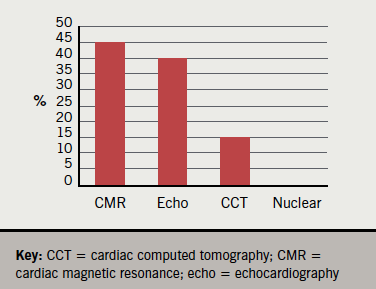

As in previous surveys, we asked trainees to state their preferred primary subspecialty (figure 1). These responses have been previously discussed.4 They demonstrate a general trend (2004–2012) for reduction in coronary intervention and general cardiology as subspecialty choices, a stable proportion preferring electrophysiology (EP) and increasing preference for imaging (especially cardiac magnetic resonance [CMR] and cardiac computed tomography [CCT]), heart failure and complex device implantation. The result is a more balanced distribution of trainees across an increasing range of cardiology subspecialties.

We asked those who selected non-invasive imaging as a primary subspecialty choice to indicate their preferred imaging modality. CMR (45%) and specialist echocardiography (40%) were clear favourites, with 15% selecting CCT. In this sample, no one selected nuclear cardiology as a preferred primary imaging modality (figure 2).

Challenges in training

We asked trainees to describe which subspecialty areas they find most difficult to access training in (figure 3). Imaging (CCT, 37% of trainees, and CMR, 34%) was consistently the most commonly cited. As in previous surveys, adult congenital heart disease (31%) and paediatric cardiology (30%) were also challenging to access for a significant minority.

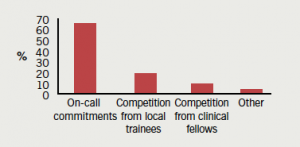

Of trainees, 61% confirmed that their training had been negatively affected by an insufficient number of sessions available to them. In this group, the most commonly cited reasons for this were on-call commitments (66%) with competition from other local trainees (19%) and clinical fellows (10%) constituting the majority of the remainder (figure 4).

When asked about the nature of disruption to training, 68% of trainees reported that hours limitation from the EWTD restricted their access to training, 57% cited cardiology on-call commitments and 45% general medicine on-calls as restricting training.

Working patterns

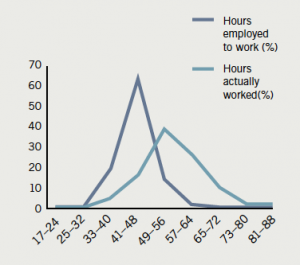

The majority (82%) of trainees are employed to work 48 hours or fewer (as directed by the EWTD: averaged over six months, weekly hours must not exceed 48), though 15% describe being employed to work 49–56 hours per week. The reported hours worked are much higher (figure 5). Only 21% of all trainees describe working within a 48-hour weekly restriction: 40% of responders report working more than 57 hours per week, with a small proportion (3.5%) working between 70 and 90 hours.

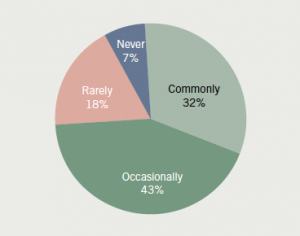

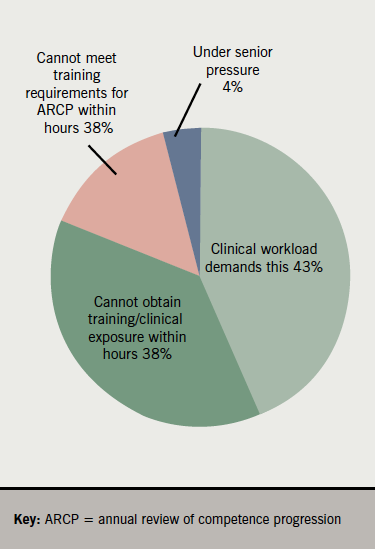

We then asked whether trainees chose to work on days off or after nights (figure 6). Three quarters do so commonly (32%) or occasionally (43%), while only 7% report never doing so. It was clear from ‘free text’ comments that many trainees did not resent this but saw it as a necessity to ensure adequate training exposure and/or procedure numbers. Although, clinical workload (43%) was the most common single reason for working on days off, working to achieve stipulated training requirements (15%) and sufficient clinical exposure (38%) accounted for 53% of responses (figure 7).

Procedure numbers

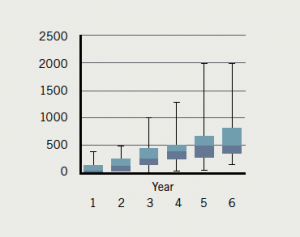

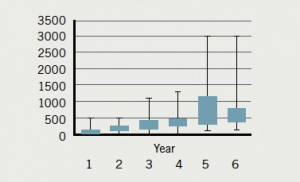

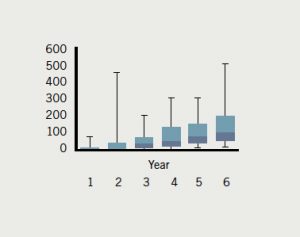

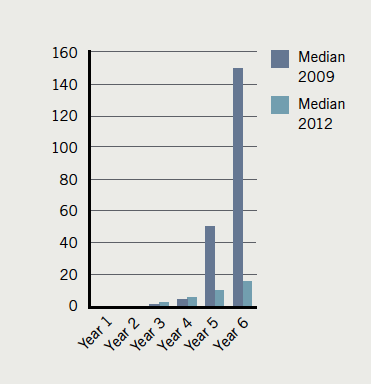

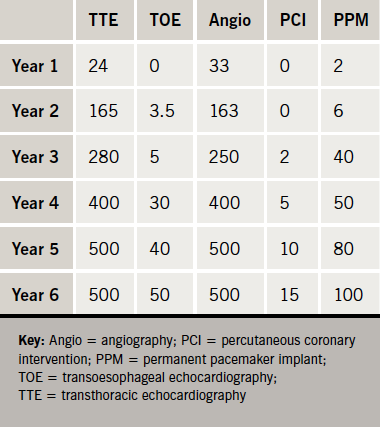

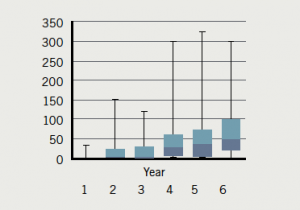

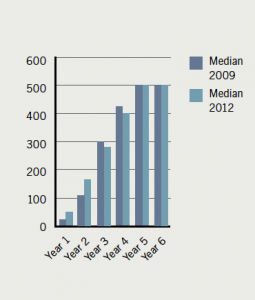

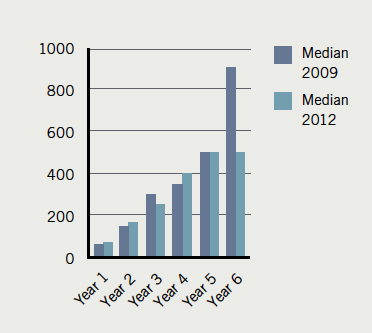

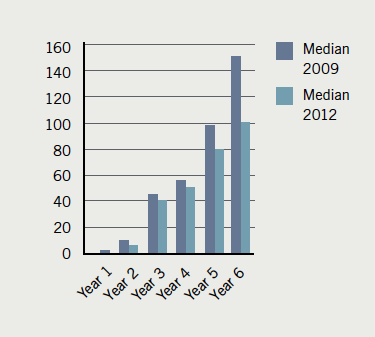

Data on procedure numbers are available, for the first time, from the 2009 and 2012 surveys. Tables 1 and 2 show the median procedure numbers for trainees from each year of training (2012). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE), diagnostic angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and pacemaker device insertion are displayed in more detail in figures 8–12 and median value changes in these procedures between 2009 and 2012 are compared in figures 13–17.

Trainees were asked to self-allocate to year of training. Though training is now restricted to five years only, the first ‘run-through’ trainees will not reach year 5 (ST 7) until summer 2013. The 2009 and 2012 cohorts include specialist registrar (SpR) trainees completing six years of specialist training. These data suggest that the cohort of year 5 and 6 trainees of 2009 have achieved significantly higher procedure numbers in TOE, PCI and pacemaker implantation than the 2012 cohort. The trend is less marked in diagnostic angiograms and numbers appear equivalent in terms of TTE numbers. This may reflect the impact of EWTD and service provision on reducing training time. In addition, it is also possible that a group of trainees are emerging who have both commenced their training sooner after graduation, and are also progressing through specialist training more rapidly. The preservation of median TTE numbers may reflect the increasing number of trainees pursuing an imaging subspecialty choice.

ARCP and representation

We asked trainees if the annual review of competence progression (ARCP) format “successfully addresses training issues?”: 52% of trainees said no; 66% did not feel that the ARCP process reflected their clinical ability.

Only 64% felt that their views were adequately collected and expressed to the British Cardiovascular Society – a spur to the BJCA to do better in this area. However, a higher proportion, 83%, felt well informed about forthcoming regional and national cardiology courses and events.

Study leave

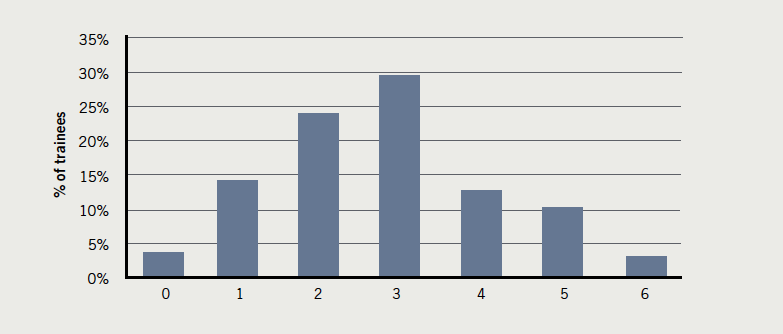

The majority (72%) of trainees attend between one and three courses or meetings per year (figure 18).

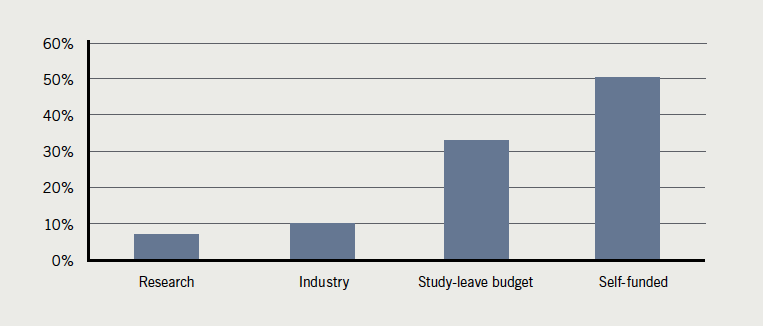

Trust study budgets fund 33% of educational events, while 50% of events are self-funded. Research (7%) and Industry (10%) account for a small proportion of educational events (figure 19).

Fellowships, research and academic medicine

Of trainees, 10% have already completed a clinical fellowship, with a further 56% planning to do so. Only one in three trainees (34%) do not plan to complete a fellowship programme. The majority of trainees intend to undertake their fellowship in the UK (18%) or other EU nations (39%). The most popular destination outside Europe is Canada (15%), with Australia and New Zealand jointly accounting for 9%.

Three-quarters (73%) of trainees anticipate completing a fellowship during training with the remainder (27%) planning a post-certificate of completion of training programme. Increased clinical experience is cited by 78% as their principal reason to complete a fellowship, with 20% stating securing a consultant position as their main motivation.

Of trainees, 59% have already completed a period of research (42% PhD, 58% MD; approximately half prior to obtaining national training number [NTN] and half during training). Of the 41% who have not yet undertaken research, 66% plan to do so. Consequently, only 8% of trainees do not plan to do any formal postgraduate research. In spite of this, only 29% feel that postgraduate research should be a prerequisite for obtaining certificate of completion of training.

Of trainees, 32% wish to pursue an academic career. For the remainder, who do not, they cite lack of interest (28%), difficulty balancing academic and clinical workload (27%) and the pressure to publish (20%) as the main reasons.

Conclusion

This year’s survey of UK cardiology trainees is the first to report since the implementation of a new cardiology curriculum; the Modernising of Medical Careers (MMC)-directed change to a shortened specialty training, comprising a core-cardiology component of three years followed by a modular subspecialty period of two years, and the 48-hour working week restriction of the EWTD.

The survey reveals a predominantly male group of trainees, albeit with a steadily growing female minority, which is more ethnically diverse than at the start of the survey eight years ago. One fifth of trainees completed their undergraduate medical training overseas.

Trainee subspecialty choices reflect the continuing super-specialisation and subdivision of cardiology – into an increasing number of popular diagnostic and interventional subspecialty areas. Imaging, in particular, is an area of rapid growth, as measured by trainee indication of subspecialty preference. This is also cited as the area of greatest challenge in terms of access to training.

It is clear that the majority of trainees do not feel able to work and train within the hours-limit directed by EWTD. The majority exceed these hours and also work unpaid, on days off, or after nights, to complete clinical work, further their exposure and to fulfil training requirements. It is also clear that most trainees do not begrudge this activity, but regard it as a necessity. In spite of this, a comparison of procedure numbers by senior trainees between 2009 and 2012 shows that median procedure numbers have fallen considerably. An exception to this trend is TTE, in which median study numbers are maintained.

Perhaps reflecting the perceived dearth of consultant jobs in prospect and the level of competition to secure a post, the vast majority of cardiology trainees incorporate both a research degree and fellowship (mostly in Europe) into their training plan.

This survey underlines some of the key challenges inherent in the reduction of trainee hours, increased demands of general medicine service provision and increased array of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques in which cardiologists must be trained. The BJCA continue to liaise closely with the cardiology specialty advisory committee (SAC), informed by these data, to attempt to provide optimum, standardised, national cardiology training, in the face of a dynamically developing specialty within a hard-pressed health service.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Azeem Ahmad and Dill Hussain, at the British Cardiovascular Society, for their generous help in running the survey.

Conflict of interest

None declared

David Holdsworth

Specialty trainee year 5 in cardiology and general medicine, Oxford Deanery, President of the BJCA.

(davidholdsworth@doctors.org.uk)

Editors’ note

Also see Editorial by Niall Keenan

(doi: 10.5837/bjc.2013.001)

References

- Kelly D, Gale C. 2007 BJCA survey of cardiology trainees. Br J Cardiol 2008;15:134–6.

- Myerson S. 2005 BJCA survey of cardiology trainees. Br J Cardiol 2006;13:102–04.

- Greenwood J, Myerson S. National survey gives unique picture of trainee cardiologists. Br J Cardiol 2004;11:440–2.

- Holdsworth D. Changes and challenges in cardiology training. BMJ Careers. Available from: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20009602