Non-statin lipid lowering was the focus of several studies reporting at the recent American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions in Chicago, USA. It was dominated by results from IMPROVE-IT, the first outcome study to show clinical events being reduced by a non-statin lipid lowering agent. Results from the ODYSSEY studies with PCSK9 inhibitors also reporting at the meeting continue to look promising with dramatic reductions in cholesterol seen. There was also good news for the long-term use of statins reported at the meeting. 20-year follow-up in the WOSCOPS study show a lifetime benefit after five years statin therapy and confirmation of their safety.

With clinicians increasingly asking how low can we go with cholesterol lowering, this report puts these studies in perspective for UK practice as well as summarising key results. Some of the physicians we interviewed here also talk about the implications of the studies in our AHA podcast.

IMPROVE-IT: ‘even lower is even better for LDL’

The IMPROVE-IT trial has made history in being the first major clinical outcome study to show a benefit of low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-lowering with a non-statin drug, and is being seen as proof of the ‘lower is better low-density lipoprotein (LDL) hypothesis.

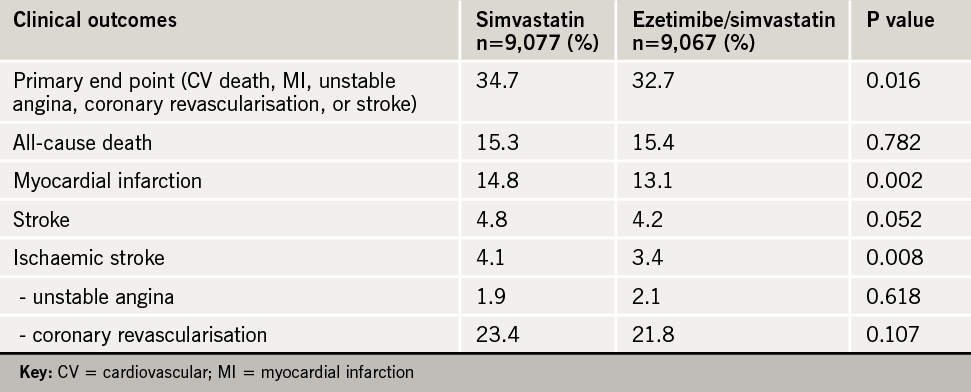

In the trial, the addition of ezetimibe to simvastatin for seven years led to a LDL lowering of 15 mg/dL (0.4 mmol/L) which was associated with a relative risk reduction in major cardiovascular events of 6.4% in patients who had recently suffered an acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial) enrolled 18,144 patients within 10 days of an ACS with LDL levels less than 125 mg/dl (3.2 mmol/L) or less than 100 mg/dl (2.59 mmol/L) if they were already on a statin. They were randomised to simvastatin 40 mg with or without ezetimibe 10 mg. Average baseline LDL level was already quite low at 95 mg/dl (2.45 mmol/L). This was lowered to 69.5 mg/dl (1.8 mmol/L) in the simvastatin alone group and 53.7 mg/dL (1.39 mmol/L) in the simvastatin plus ezetimibe group.

Key results

Presenting the results (table 1), Dr Christopher Cannon (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA), said this is the “first trial demonstrating an incremental clinical benefit when adding a non-statin, cholesterol-lowering agent to a statin, and has proven that even lower LDL is even better.”

One of the UK investigators, Dr Mark Signy (West Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust) elaborated for the BJC: “We have been struggling with anything that isn’t a statin. Everything else has been discredited or shown very limited benefit. It means we have something else to use.”

He added: “We’ve been waiting for this for years. Now we know that ezetimibe works. And even if patients have low LDL levels it is worth pushing them even further down. The control group in this study reached 1.7–1.8. That’s a good low level to start with. But they still showed significant benefit from going even lower when ezetimibe was added.”

Dr Signy also highlighted the clean safety profile with ezetimibe in the study. “There was absolutely no sign of adverse effects, putting paid to concerns about possible increase in cancer seen in the previous SEAS study. IMPROVE-IT was much bigger and longer and no sign whatsoever of a safety risk.”

Implications for clinical practice?

Although patients in IMPROVE-IT were high risk (all post-ACS), Dr Signy thinks the results can be extrapolated to other situations. “There is no argument that ACS patients need aggressive treatment. But I don’t think the use of ezetimibe will be limited to this population. You have to do the mega trials in these high-risk groups as it is difficult to show incremental benefit in lower risk groups, but I think we can assume it works in any population if it is lowering LDL. But no-one is advocating using it in primary prevention at the moment unless patients can’t take statins or have familial hypercholesterolaemia.”

The current recommendation is to raise the dose of statin − up to 80 mg of atorvastatin − in high risk patients such as those with ACS. While IMPROVE-IT did not look at adding ezetimibe to atorvastatin 80 mg Dr Signy believes the results can be applied here.

“We couldn’t possibly study ezetimibe on top of every single statin. But what we have shown is that when you add ezetimibe on top of a statin there is additional benefit. Most people start on atorvastatin 40 mg now. I think you now have a choice as to the next step. You can increase the atorvastatin to 80 mg or you can add ezetimibe. Or you can increase atorvastatin to 80 mg and then add ezetimibe. I can’t see a problem extrapolating the IMPROVE-IT results to these situations.”

He believes the choice of adding in ezetimibe at a lower statin dose will be an attractive option for those worried about side effects of high statin doses. “I’m not sure about official statin intolerance but many people do discontinue these drugs especially at higher doses. Now we have an alternative to going to high dose statins − use a moderate dose plus ezetimibe.”

Dr Signy also points out adding ezetimibe would give a greater LDL reduction than increasing the statin dose. “If you double the statin dose you are looking at an additional 7% LDL reduction. Whereas adding ezetimibe gives an extra 20% reduction,” he notes.

‘It should not be viewed as statin sparing’

Another UK lipid expert is adamant that the IMPROVE-IT results should not be seen as a “statin sparing” option.

Professor Kausik Ray (St George’s Hospital NHS Trust, University of London) points out that the amount of LDL lowering in IMPROVE-IT − a 2% absolute benefit over 7 years − was “relatively modest”. He notes that the previous PROVE-IT trial showed a much larger reduction in events with atorvastatin 80 mg versus lower dose statins, although this was in a higher risk population. “PROVE-IT showed a 2% absolute benefit per year. That is much more impressive and so for me, maximum dose statins must always be the first step for ACS patients.”

“After IMPROVE-IT, I think we can put ACS patients straight on atorvastatin 80 mg plus ezetimibe. And we will get a 70% LDL lowering. Or we could start with atorvastatin 80 mg and if LDL is not below 1.8 or so after a few months, add in ezetimibe. But what I hope will not happen after this data is that doctors will think they can use atorvastatin 40 mg plus ezetimibe instead of starting with atorvastatin 80 mg. There is no evidence that this is the right thing to do.”

Professor Ray believes concerns about the side effects of statins have been overblown. “The risk of side effects is very low as shown by objective systematic reviews. And they are symptoms rather than permanent damaging effects. It has been hyped in the media and has led to public hysteria. Muscle aches are the most common complaint but almost as many people have these on placebo too. I’ve been prescribing atorvastatin 80 mg for years with very little problem.”

He adds: “Traditionally we use ezetimibe in patients with very high LDL levels despite statins. That is where it will continue to be used mainly but with more confidence as we now have proof it works and is safe.”

The IMPROVE-IT investigators reported that in terms of clinical event reduction per g/dl reduction in LDL, ezetimibe has the same impact as statins. But Professor Ray is not sure about that. He points out: “When you plot a graph of LDL reduction in relation to clinical event reduction seen with all the statin trials, the IMPROVE-IT result falls below the regression line. Yes the confidence limits overlap so it does support the LDL hypothesis but data on the statins are still much stronger.”

Impressive results in diabetes

Professor Anthony Wierzbicki (Guys and St Thomas Hospital, London) says IMPROVE-IT provides reassurance on ezetimibe. “We’ve all used ezetimibe but it has been quite a controversial drug. There have always been questions from surrogate marker studies about whether it is doing anything useful apart from lowering LDL. IMPROVE-IT has shown us that it is.”

He says he is comfortable extrapolating the results to patients taking atorvastatin 80 mg “who will get some extra benefit by adding in ezetimibe”.

Professor Wierzbicki makes the point that current guidelines are focused on risk rather than LDL level, and results from the population with diabetes in IMPROVE-IT suggest that the benefits of ezetimibe will be greater in higher risk patients.

“The number need to treat to prevent one event was approximately 50 in the whole population. But in diabetics it was around 35. We might see the same phenomenon in smokers and other groups who have a higher absolute event rate where we would expect to see a greater absolute benefit.”

The UK clinical recommendations will have to be formulated by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which Professor Wierzbicki says will focus on cost-effectiveness. “At about £25–£30 per month, I think it is likely they will consider it cost-effective in ACS patients. Chronic coronary disease may be more debatable. But the data in diabetics is very impressive. I would think that ezetimibe may well be cost-effective in secondary prevention for high-risk groups.”

“Everything will change of course when ezetimibe comes off patent in 2017−2018. There will be far wider usage then. Until then there are bound to be some restrictions In the UK. But these will be a lot less prescriptive than they have been,” he adds.

View from general practice

Dr Terry McCormack, (a general practitioner from Whitby, North Yorkshire) is also impressed with the IMPROVE-IT results. He comments: “There has been confusion over IMPROVE-IT. It looks like a small benefit − only a 6.4% relative risk reduction. But in these patients who already had quite good LDL levels and were taking an adequate statin dose as baseline there was not much room to make a difference. That is probably the best that could be achieved. This is not the normal population we would think about using ezetimibe in, and the study has proved the drug works.”

“The patients who I use ezetimibe in most now are those with high LDL who cannot reach decent levels on statins alone. Yes, I will add ezetimibe in to atorvastatin 80 mg for my ACS patients, but I hope now I can also use it more freely in other patients who need better LDL lowering.”

Dr McCormack notes that in some areas of the UK, payment schemes have been actively discouraging GPs from using ezetimibe. “This is a major problem and will have to be rethought now,” he says.

ODYSSEY programme completes and PCSK9 inhibition continues to show ‘impressive’ LDL lowering

Several phase 3 trials – all under the ODYSSEY banner with the new PCSK9 inhibitor, alirocumab − reported at the AHA meeting and all showed dramatic reductions in LDL. These complete the ODYSSEY programme of studies and alirocumab is now being submitted for approval for LDL lowering. Outcome trials are also underway to support more extensive use.

ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE: alirocumab suitable option for statin intolerant patients

Alirocumab may be a good option for patients intolerant to statins, according to the results of the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trial.

Dr Patrick Moriarty (University of Kansas Medical Center, USA), who presented the study at the meeting, concluded: “In patients who are truly statin intolerant, alirocumab may be a suitable alternative therapy for them. But long-term safety and efficacy must be studied.”

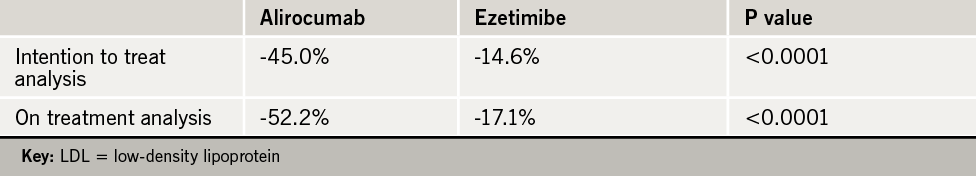

For the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trial, 361 patients with mean baseline LDL of 190 mg/dl (4.91 mmol/L) underwent a four-week placebo run-in phase and were then randomised to alirocumab 75/150 mg subcutaneously every two weeks (n=126), ezetimibe 10 mg once daily (n=125) or atorvastatin 20 mg once daily (n=63). After 24 -weeks of blinded treatment, they continued on open label alirocumab for a mean of 14 weeks.

During the placebo run-in phase, 47 patients dropped out, half because of muscle related symptoms, “highlighting the extreme sensitivity of this population,” Dr Moriarty noted. During the blinded treatment phase, 23% of alirocumab patients also stopped treatment, versus 33% in both other treatment arms.

As expected, alirocumab was associated with a larger reduction in LDL than the ezetimibe group (table 2). The LDL reduction in the atorvastatin arm was not formally presented, but during the discussion Dr Moriarty reported that this was about 20%.

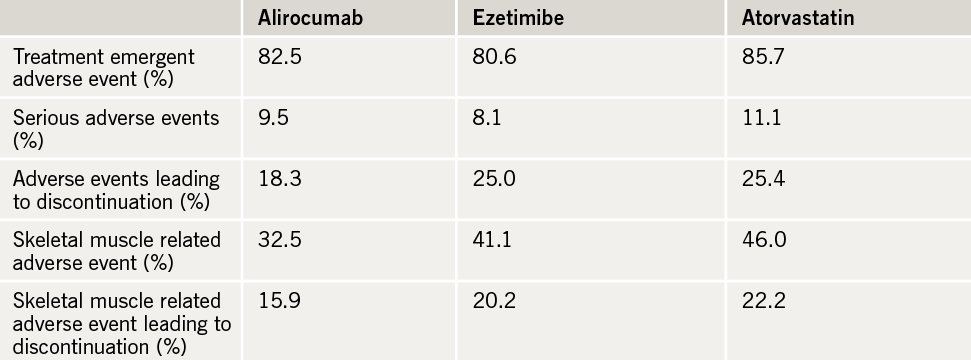

The vast majority of patients reported some adverse events with each of the three treatments, again demonstrating the difficulty in treating these patients, who Dr Moriarty said were often intolerant to many other drugs.

Statin intolerance

Of interest, 75% of patients labelled as statin intolerant managed to stay on blinded atorvastatin 20 mg for this study. Dr Moriarty commented: “This shows that many patients who think they are statin intolerant may actually be able to be treated with low-dose statins. But alirocumab was still better tolerated and was associated with fewer skeletal muscle adverse events” (table 3).

Adherence was better in the open label alirocumab treatment phase, during which 56% of patients reported an adverse event but this caused discontinuation in just 3%.

Dr Moriarty said impressive LDL lowering with the PCSK9 antibodies would be “particularly useful” in this group of patients who struggled to tolerate adequate doses of statins. He did not view the need for an injection as a problem. This population, he said were “willing to sacrifice some convenience to get their LDL down”.

Commenting to the BJC, Professor Robin Choudhury (Oxford University) said the trial “really throws considerable question on the precision of diagnosis of statin intolerance. Many patients who are thought to be intolerant can − with additional reassurance − persist with the drug, which is important given that statins have a very worthwhile track record, particularly in the secondary prevention of complications from atherosclerosis.”

On where the PCSK9 agents may fit in UK clinical practice, Dr Chris Packard (University of Glasgow) commented to the BJC: “They are injections and they will be expensive. But they lower LDL very impressively. I would see them being used in severe heterozygous FH patients, and in those with a strong history of heart disease in whom LDL is not controlled with statins and ezetimibe.”

Dr Terry McCormack (a GP from Whitby, Yorkshire) thinks the PCSK9 antibodies are “a very exciting development.” He commented: “This will be the future. They are so much more powerful than anything we have had before. The impact on LDL is immense − up to a 60% reduction.”

Dr McCormack predicts that these agents will initially be used mainly in FH patients but “if the outcome trials are positive I can see them being prescribed extensively for secondary prevention,” he said.

He pointed out that outcome trials for all new cholesterol drugs have been requested after questions arose about ezetimibe in the ENHANCE trial. “But those concerns have now been allayed in IMPROVE-IT. The FDA may well rethink things now we have further evidence of the LDL hypothesis. I think we have to ask whether we are harming people by waiting?”

ODYSSEY LONG-TERM: encouraging reduction in clinical events

Latest data from pooled ODYSSEY studies evaluating alirocumab suggest “very encouraging” clinical event reduction, it was reported at the meeting.

Dr Jennifer Robinson (University of Iowa, USA) presented latest long-term data on alirocumab from the ODYSSEY LONG-TERM study and also from a pooled analysis of all phase 3 placebo-controlled trials with more than 52 weeks follow-up. Both these analyses − which involved mainly patients with cardiovascular disease and high LDL levels at baseline or those with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) − suggested large reductions in clinical events with the PCSK9 inhibitor, as well as impressive LDL reductions.

The ODYSSEY LONG-TERM study randomised 2,300 patients to alirocumab (150 mg every two weeks) or placebo (on top of maximum tolerated statins). Results at 65 weeks show a 60% reduction in LDL and a 54% reduction in cardiovascular events (a composite of MI, stroke, cardiovascular death and unstable angina) with alirocumab versus placebo, with a P value of 0.016, Dr Robinson reported.

A post-hoc pooled analysis of all phase 3 placebo controlled trials with more than 52 weeks follow-up of 3,459 patients, showed a 35% reduction in events on alirocumab which didn’t reach significance (p=0.09). Dr Robinson said:. “The curves separate early and stay separate.”

“Subgroup analysis shows LDL is consistently reduced by 55−65% in all patient groups.

And the safety also looks very good, with no indication of an increase in adverse events in patients getting down to LDL levels less than 25 mg/dl (0.6465 mmol/l),” she commented.

Other ODYSSEY studies

Another four studies reporting at the meeting – all part of the ODYSSEY programme – also showed large reductions in LDL with alirocumab (75 or 150 mg every two weeks) when given on top of statin therapy over 24 weeks of treatment. The other four studies – known as ODYSSEY COMBO I, OPTIONS I, OPTIONS II, and HIGH FH involved patients who had high LDL and were at high cardiovascular risk, or had FH. In the whole ODYSSEY trial programme, alirocumab was associated with a 36−62% reduction in LDL from baseline. In the trials that used an individualised approach with 75 mg and 150 mg doses, the majority of patients reached their LDL goal while remaining on the 75 mg dose.

Most common side effects were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection site reactions, urinary tract infection, back pain, and myalgia/arthralgia. Sanofi and Regeneron report that the overall rate of discontinuations for skeletal muscle adverse effects across the phase 2 and 3 alirocumab placebo-controlled studies, where the majority of patients were also on statins, was 0.4% for alirocumab (n=2,476) and 0.5% for placebo (n=1,276).

Implications for practice

So what are the implications of these impressive reductions in LDL lowering with PCSK9 inhibition for practice? Dr Robinson told BJC that similar data have been seen with another PCSK9 agent in development – evolocumab. “There are more patients followed for longer with alirocumab. But it is good to see consistent data across the class,” she said.

She added: “These data are not the same as those from a proper outcomes study, but they are very encouraging. We will have to wait for the large outcome trials to know for sure about cardiovascular event reduction, but these agents are being submitted for approval for an LDL reduction indication before the large outcome trials are available. The current data will help to support those applications.”

On how she sees the PCSK9 antibodies being used, Dr Robinson said: “We need safe and effective agents to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with genetically high cholesterol and those who are statin intolerant. This is the near term unmet need.

Then we are using the next generation of trials to look at the question of how low should we go with LDL. We are getting people down to under 25 mg/dl (0.6465 mmol/l). That is very exciting.”

Dr Michael Koren (Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research, USA) who is involved with clinical trials of both alirocumab and evolocumab told the BJC: “Both these agents are showing impressive 50−60% reductions in LDL and outstanding safety so far. And the new data on early outcomes from long-term safety studies underway is certainly trending in a favourable direction. We do have to be careful as these studies are not powered to evaluate outcome. They are there to look at safety but we do also look at what is happening to the outcomes, and we are seeing a 50% or so reduction in events. I don’t want to oversell this but it does look very promising.”

He added: “There have been some safety concerns voiced from epidemiological studies about very low LDL levels but the only people who get such low levels of LDL naturally are people who are sick. We don’t think this really applies to therapeutically lowering LDL to these levels. We are crossing a new threshold and so far we are not seeing any safety concerns − just less cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.”

Commenting on the data for the BJC, Dr Kausik Ray (St George’s Hospital NHS Trust, University of London) said: “The main message is that there is no signal in terms of harm. And there is an encouraging trend for benefit. But we don’t want to be getting too excited about this yet. These are relatively small studies with short follow-up. We have to sit it out and wait for the real outcome studies now underway.”

He added: “When you get a whopping great reduction in LDL like these drugs give, I don’t think we are necessarily going to get a 50% reduction in event rate. Possibly a 35% reduction would be wonderful. That’s what we are hoping for.”

Professor Ray agrees with others that these agents will start off being used in very high-risk patients. “In time they will probably see broader use but they are antibodies and will be expensive and costs are bound to limit their use to some degree.”

WOSCOPS: statin benefits remain after 20 years

Long-term follow-up of patients in WOSCOPS (West of Scotland Primary Prevention Study) has shown that the benefit of five years of statin use remains 20 years later.

The WOSCOPS trial involved 6,595 men who were randomised to 40 mg/day of pravastatin or placebo. Published in 1995, it showed that five years of pravastatin was associated with a 31% reduced risk of cardiovascular death /MI. At the end of the randomisation phase, patients were referred back to their own doctors for continued treatment and around 30% from each arm ended up ongoing statin therapy.

For the long-term follow-up, Dr Chris Packard (University of Glasgow) and colleagues used electronic medical records to link to death registers and hospitalisation records, and found that patients in the original pravastatin arm had a 27% reduced risk of coronary heart disease mortality, and a 13% reduced risk of all-cause mortality. The need for coronary revascularisation was reduced by 19%, and heart failure by 31%.

Dr Packard reported that 2,457 cardiovascular events occurred in 1,044 patients in the pravastatin group, versus 3,007 cardiovascular events in 1,209 patients in the placebo group. “This is highly statistically significant with a P value less than 0.0001,” he said.

To the BJC, Dr Packard noted: “Our results cover the prime period of premature cardiovascular outcomes as these people were enrolled at the average age of 55 and will now be average 75. We see a lifetime benefit of reduced cardiovascular morbidity/mortality in the treated group which translated into a 20% reduction in hospital days for cardiovascular outcomes.”

The long-term results also confirm the safety of statins. Dr Packard said: “There was no effect at all on non-cardiovascular events. There was no safety signal at all over a 20 year follow-up in terms of cancer or anything else so there is no disadvantage of treatment. People can be reassured that statin use is not associated with any long term safety concerns.”

Commenting for the BJC, Professor Kausik Ray said: “This is important news because it is more evidence against the cholesterol skeptics. There was a clear separation of curves that continued over the very long term, and it is reassuring to see a reduction in all-cause mortality.”

He added: “This shows starting treatment early gives a long-term benefit. If you start later you are not going to catch up.”

Professor Ray also noted pointed out that pravastatin is a relatively weak statin and larger benefits would be expected with the drugs used today. “Pravastatin gives about a 25% reduction in LDL. Today we would be using atorvastatin 20 mg in the primary prevention population which gives a 36−38% LDL reduction, ” he said.

More reports from AHA available online

If you would like to read more from the AHA, a round-up of news from the AHA is available here. Studies covered include optimal dual antiplatelet therapy after stenting, a Japanese primary prevention study with aspirin, the use of oxygen in ST-elevation MI, whether mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is more effective than manual CPR, aspirin use and oral anticoagulation, the incidence of endocarditis post-dental surgery after antibiotic ban, and the link between trans fats and memory.