Presentation of an interrupted aortic arch in adulthood is rare, and, up until, recently the only treatment strategy was through surgical repair. Advances in percutaneous interventions for congenital heart disease have included the percutaneous repair of coarctation of the aorta – from straightforward luminal narrowing through to full aortic interruption.1-3 We present a case of a 28-year-old man who was diagnosed with a complete aortic interruption and successfully percutaneously treated.

Case

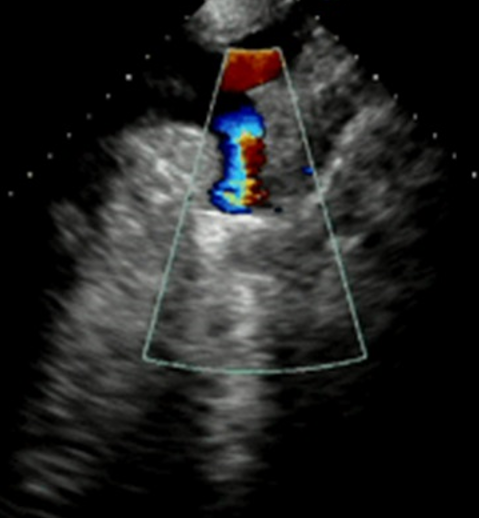

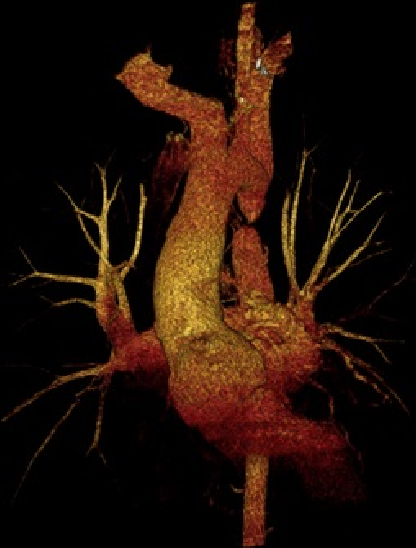

An asymptomatic 28-year-old man with an incidental finding of hypertension at a routine visa renewal medical presented to outpatients for review and further investigation. Significant radiofemoral delay was found on palpation of pulses, and an ejection systolic murmur heard over the praecordium. Blood pressure was recorded as 190/70 mmHg, despite therapy including irbesartan 300 mg, amlodipine 5 mg and atenolol 50 mg. Transthoracic echocardiogram was performed showing severe concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, mild aortic regurgitation and an apparent cessation of flow in the descending aorta (figure 1). No significant intra-aortic gradient was found. Trans-oesophageal echocardiography revealed the presence of a bicuspid but functionally normal aortic valve with mild aortic incompetence. Computed tomography (CT) aortogram was then performed, revealing absence of luminal continuation of the aorta, leading to diagnosis of interruption of the aorta at a level distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery (figure 2). Collateral circulation from intercostal, periscapular and internal mammary arteries allowed circulation to the more distal segment of the thoracic and abdominal aorta (figure 3). Plain film chest X-ray demonstrated inferior rib notching secondary to the hypertrophied intercostal arteries (figure 4).

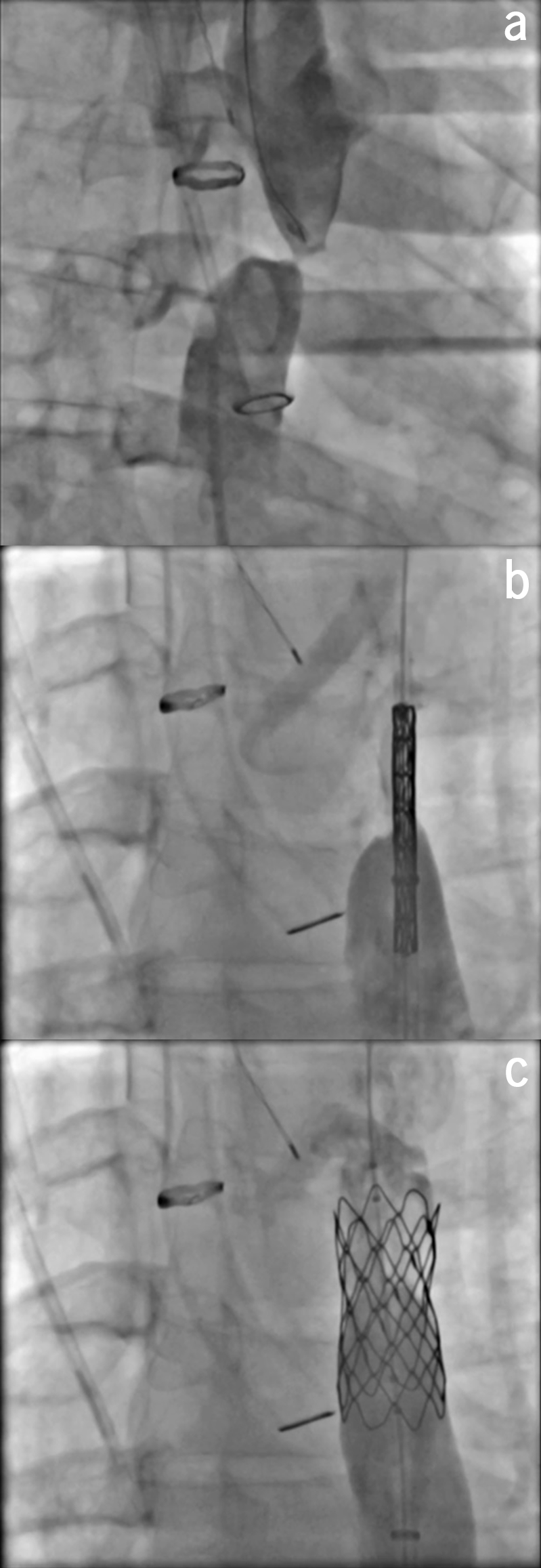

Following multi-disciplinary team discussion, elective percutaneous endovascular repair was performed in the hybrid catheterisation laboratory under general anaesthesia. The procedure was performed percutaneously via access at the left brachial artery and right femoral artery. Simultaneous angiography confirmed the atretic aorta (figure 5a). Probing with CT wires failed. A medical power wire was used with radical frequency energy applied for 2 seconds. The power wire was then snared out from the descending aorta and a multi-purpose catheter was pulled through into the descending aorta and a stiff guide wire was exchanged with the power wire. A Nudel premounted sheathed covered Cheatham Platinum stent was then inserted, 16 mm x 3.9 cm in size (figure 5b). Angiography showed the area to be widely open (figure 5c), and haemodynamic studies confirmed no significant gradient across the area (15 mmHg). The right brachial artery was closed with manual pressure and the femoral artery was closed by tying down proglide sutures.

Post-intervention, repeat transthoracic echocardiogram at six months revealed some improvement in left ventricular hypertrophy. Repeat CT aortogram was performed, showing both accurate placement of the stent (figure 6) and an interval reduction in the calibre of collateral circulation (figure 7), with good flow through the endovascularly repaired interruption. His antihypertensive regimen remained unaltered due to persistent hypertension post-procedure, and he will be enrolled in lifelong follow-up to attempt to achieve normotension.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Santoro G, Russo MG, Calabro R. Stent angioplasty in aortic arch interruption. Heart 2006;92:1570. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.085746

2. Goel P, Moorthy N. Percutaneous reconstruction of interrupted aortic arch in an adult. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:21–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2012.11.012

3. Jha N, Tofeig M, Kumar R et al. Stent dilatation of atretic aortic coarctation in an adult. J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;11:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-016-0395-1