Body mass index (BMI) was first proposed in 1835 as a way to standardise body composition assessment for people of different heights, at a time when malnutrition was the main public health concern. BMI has been considered appropriately as a part of nutritional assessment in populations. It is not, however, a useful tool for assessment of individuals because there is so much individual variability in body composition and in its impact on health outcomes. Similarly, high BMI does not distinguish between excess body fat (bad for health) and large muscle mass (good). In contrast, we propose that individuals need to be assessed using clinical criteria, monitored over time to trigger different interventions. A diagnosis of obesity should be based on estimates of body fat (BMI, now being replaced by percentage body fat) at a particular age, and a clinical staging system.

Introduction

It is time to adopt recent (and even some 20th century) evidence for obesity and weight management. Some aspects of current practice, both clinical and epidemiological, are still largely lodged in the mid-19th century.

The body mass index (BMI) was first proposed in 1835 by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician, as a way to standardise body composition assessment for people of different heights. His work was published in the English language a few years later.1 At that time, few people, mostly affluent, had a BMI above 30 kg/m2, and far fewer had type 2 diabetes. The main public health concern was malnutrition, and BMI <18.5 kg/m2 does commonly point to undernutrition. Our needs for 21st-century public health and clinical practice are very different, much more focused on obesity and the secondary chronic metabolic diseases. However, still the main (and often sole) information provided in national surveys is BMI,2,3 and sometimes BMI is used and recommended inappropriately in clinical settings. For example, in England, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides this guidance for assessing individual patients: “Identify people eligible for referral to lifestyle weight management services by measuring their body mass index (BMI). Also measure waist circumference for those with a BMI less than 35 kg/m2.”4 Similarly, the Scottish government’s obesity strategy: “Adults can be classified into (conventional) BMI groups.”5

There are two recurring problems here. First, while BMI has been considered, appropriately, as a part of nutritional assessment in populations,6 it is not useful to assess individuals because there is so much individual variability in body composition and in its impact on health outcomes. A BMI of 28 or 30 kg/m2 can be perfectly normal for a power sportsman, such as a rugby player in training or a heavyweight boxer, but in other people, type 2 diabetes may develop when BMI rises from 22 to 24, because extra fat is being deposited in the liver and other ectopic sites.

Second, high BMI does not distinguish between excess body fat (bad for health) and large muscle mass (good). If you know peoples’ age, sex, height, weight, waist and hip circumferences, you can estimate body fat7 and muscle mass,8 separately, using well-validated published equations. They have opposite associations with major metabolic outcomes – type 2 diabetes9 and hypertension.10 That is much more useful than BMI, which lumps together these two very different tissue components. Assessing body fat and muscle mass separately is of particular importance to identify the worrying trends towards sarcopenia, with all the health risks from frailty, especially when accompanied by obesity, and in older people.

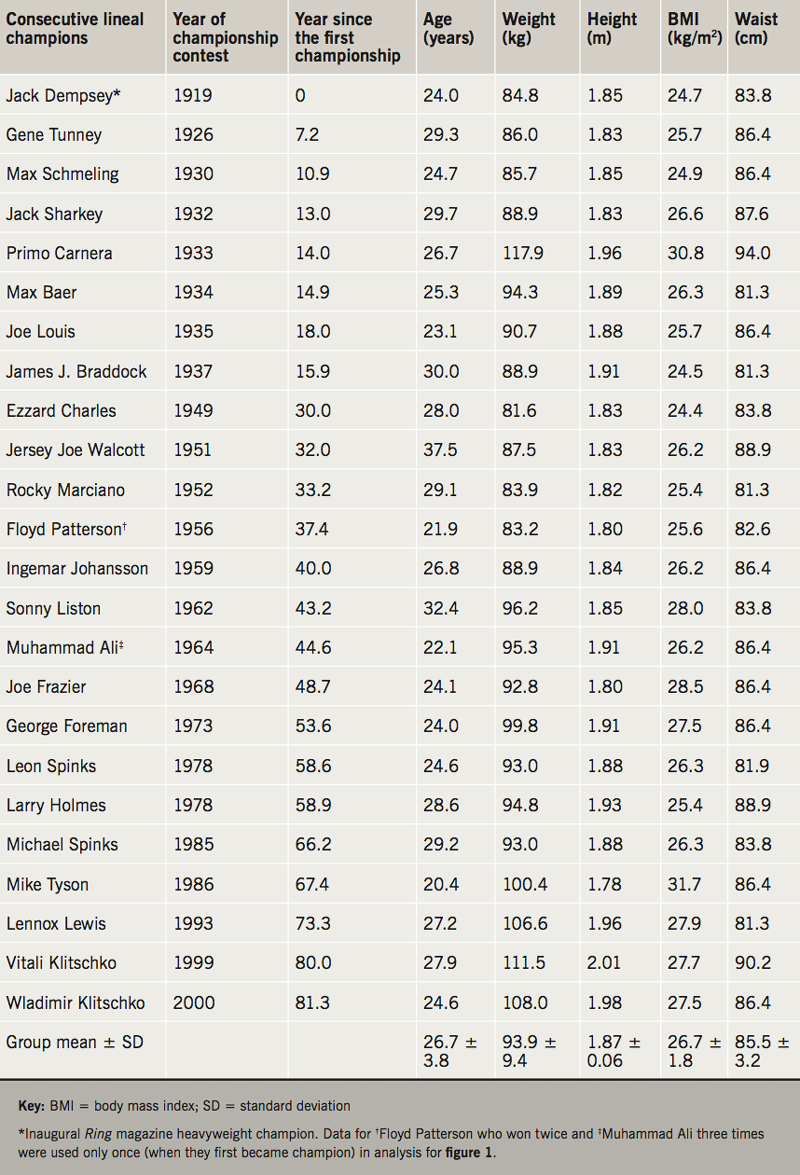

To illustrate the misleading use of BMI, we analysed 24 lineal heavyweight boxing champions in the past century, the first of whom was inaugurated by the Ring magazine in 1919.11 Their mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age was 26.7 ± 3.8 years, BMI 26.7 ± 1.8 kg/m2, and waist circumference (WC) 85.5 ± 3.2 cm (table 1). We found that the majority (75%) had a BMI over 25 kg/m2 while only one (4.2%) had a WC above “Action Level 1” (≥94 cm) (figure 1). The years in which the champions first won their title increased linearly with BMI (r=0.413, p=0.045) but not with waist circumference (r=0.015, p=0.945). These results indicate that among these elite sportsmen, there is a secular change in BMI which mirrors the changes among general populations, but does not necessarily indicate that they are getting fatter, since the size of their waist circumferences remains constantly unchanged. Increasing numbers of healthy fit individuals, who train regularly in power exercise or sports, are likely to be misclassified as overweight or even obese in health surveys.

There is, therefore, a good reason for national surveys, which include simple measurements, now to report average body fat and muscle mass in population groups, not just BMI. Waist circumference ‘Action levels’ were introduced for health promotion as an alternative to BMI, because waist size provided a more reliable guide to health risks and outcomes than BMI (recognising that waist measurement becomes unreliable with severe obesity, by which stage health risks are inevitably high). People can identify with their waist size, which relates closely to clothing size,12 so it can be helpful to monitor the waist circumference of individuals over time, as well as weight. Waist also has value in epidemiology, for estimating body fat and muscle mass using the published equations.7,8

There are no simple diagnostic criteria for ‘obesity’ or ‘overweight’ in individuals. These value-judgement terms have become synonymous with BMI cut-offs in epidemiology, but obesity is not a certain BMI level. Obesity is a disease process of excess body fat accumulation. A range of genetic, epigenetic and neuroendocrine factors contribute, and if they have causal roles in generating positive energy balance, they must be present while the weight and BMI are still low. That process of obesity generates multiple organ-specific pathological consequences, which can develop at different rates, and at different ages, with varying degrees of ultimate sickness and disability.13 So for clinical purposes, individuals need to be assessed using clinical criteria, monitored over time to trigger different interventions. The diagnosis must, therefore, be based on estimates of body fat (BMI, now being replaced by per cent body fat) at a particular age, and a clinical staging system such as the Edmonton Obesity Staging System14 or the King’s Hospital staging system15.

Key messages

- Body mass index (BMI) was first introduced to standardise body composition assessment for people of different heights

- BMI is not useful to assess individuals because there is so much individual variability in body composition and in its impact on health outcomes

- Diagnosis of obesity must now be based on estimates of body fat (BMI, now being replaced by percentage body fat) at a particular age, and a clinical staging system

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

1. Quetelet A. A treatise on man and the development of his faculties. Originally published in 1842. Reprinted in 1968 by Burt Franklin, New York. Also available from: Obes Res 1994;2:72–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00047.x

2. NHS Digital. Health Survey for England, 2016. London: National Statistics, 2017. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2016 [accessed January 2019].

3. Eurostat statistics explained. Overweight and obesity – BMI statistics, 2017. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Overweight_and_obesity_-_BMI_statistics [accessed January 2019].

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Managing overweight and obesity in adults – lifestyle weight management services. NICE public health guidance 53. London: NICE, May 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph53 [accessed January 2019].

5. Scottish Government. A healthier future – Scotland’s diet: a healthy weight delivery plan. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2018. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/Publications/2018/07/8833/355982

6. World Health Organization (WHO). Body mass index – BMI. Available at: www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi [accessed January 2019].

7. Lean ME, Han TS, Deurenberg P. Predicting body composition by densitometry from simple anthropometric measurements. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;63:4–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/63.1.4

8. Al-Gindan YY, Hankey C, Govan L, Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Lean ME. Derivation and validation of simple equations to predict total muscle mass from simple anthropometric and demographic data. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:1041–51. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.070466

9. Han TS, Al-Gindan Y, Hankey CR, Lean MEJ. Associations of BMI, waist circumference, body fat and skeletal muscle with type 2 diabetes in adults. Acta Diabetol 2019;in press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-019-01328-3

10. Han TS, Al-Gindan Y, Hankey CR, Govan L, Lean MEJ. Associations of BMI, waist circumference, body fat and skeletal muscle with hypertension in adults. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21:230–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13456

11. Wikipedia. List of The Ring world champions. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_The_Ring_world_champions [accessed January 2019].

12. Han TS, Gates E, Truscott E, Lean ME. Clothing size as an indicator of adiposity, ischaemic heart disease and cardiovascular risks. J Hum Nutr Diet 2005;18:423–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00646.x

13. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of obesity. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2010. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign115.pdf [accessed January 2019].

14. Sharma AM, Kushner RF. A proposed clinical staging system for obesity. Int J Obes 2009;33:289–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.2

15. Aasheim E, Aylwin SJB, Radhakrishnan ST et al. Assessment of obesity beyond body mass index to determine benefit of treatment. Clin Obes 2011;1:77–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-8111.2011.00017.x