In the UK, there is a difference between the medical specialties and cardiology in recruitment of women. Research, thus far, has concentrated on women already in cardiology. Although invaluable in understanding barriers to training, these studies fail to provide insight into why other trainees chose an alternative. Therefore, we designed a survey aimed at medical personnel, evaluating why higher trainees in other specialties overlooked cardiology.

An online survey was distributed via email to non-cardiology higher trainees in Wales. Questions covered previous clinical experiences of cardiology, interactions with cardiologists, and tried to identify deterrent factors.

There were 227 responses received over six weeks: 61.7% (n=137) female respondents, 23.5% (n=52) less than full-time. Of these, 49% completed a cardiology placement previously. Bullying was witnessed and experienced equally among genders, females witnessed and experienced sexism, 24% (n=24) and 13% (n=13), respectively. In contrast, male trainees witnessed and experienced sexism 14% (n=7) and 0%. There were 62% (n=133) who felt cardiologists and registrars were unapproachable. Work-life balance ranked first (40%), as the most important factor influencing career choice. The negative attitudes of cardiologists and registrars was ranked top 3 for not pursuing cardiology.

In conclusion, many barriers exist to cardiology training including poor work-life balance, sexism and lack of less than full-time opportunities. However, this survey highlights that the behaviour of cardiologists and registrars has the potential to impact negatively on trainees. It is, therefore, our responsibility to be aware of this and encourage change.

Introduction

The under representation of women in cardiology training is now a recognised shortfall that also extends into the consultant workforce. There are multiple reports of this phenomenon worldwide, including Europe,1 US,2,3 Canada,4 and Australia.5 In the UK, women make up 28% of trainees and 13% of the consultant tier.6 This is a stark difference to other medical specialties in the UK.7

In order to improve the recruitment of women into cardiology, it is important to first understand why alternative specialties are more successful at attracting a greater proportion of female trainees. Surveys to date have focused on the opinions of women who have already committed to cardiology specialist training. Although these surveys are invaluable tools in highlighting the problems facing female cardiologists in training, they do not shed light as to what has deterred their non-cardiology counterparts. In order to ascertain why trainees do not consider cardiology as a viable career option, we need to ask those who chose not to train in cardiology: higher specialty trainees in other specialties. With this in mind, we designed and distributed a survey that asks just that; why have registrars in other specialties not chosen cardiology as a career?

Method

A survey was developed using Online Surveys (formerly Bristol Online Survey, BOS. Jisc Ltd.) and distributed via email to all non-cardiology higher trainees working in Wales.

Questions were designed to cover previous clinical experiences of cardiology, opinions of cardiology trainees and cardiologists, and identify factors that may have deterred trainees from applying for the specialty. A combination of open questions, best match and Likert scale questions were used in order to probe the domains listed above.

Surveys were distributed to both female and male trainees in general practice, anaesthetics, intensive care, obstetrics and gynaecology, psychiatry, paediatrics, radiology, and all other medical and surgical specialties. The total number of trainees contacted was approximately 1,000.

After survey completion the results were analysed using Microsoft Excel and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (IBM, 2009).

Results

A total of 227 surveys were completed in a six-week period. Although our findings focus on the challenges female trainees face, we comment on the challenges for all trainees.

Demographics

Out of the total 227 responses received, 137 were from female trainees (61.7%) and 85 were male (38.3%); five trainees preferred not to say. The age of trainees ranged from 24 to 47 years, 48.9% of respondents fell into the 31–35 age range. A total of five respondents left this answer blank.

Ethnicity was made up of 70.4% white British, 7.5% British Indian, 4% British Pakistani, 3.5% Arab, 2.2% Chinese, 1.3% African and 11.1% other.

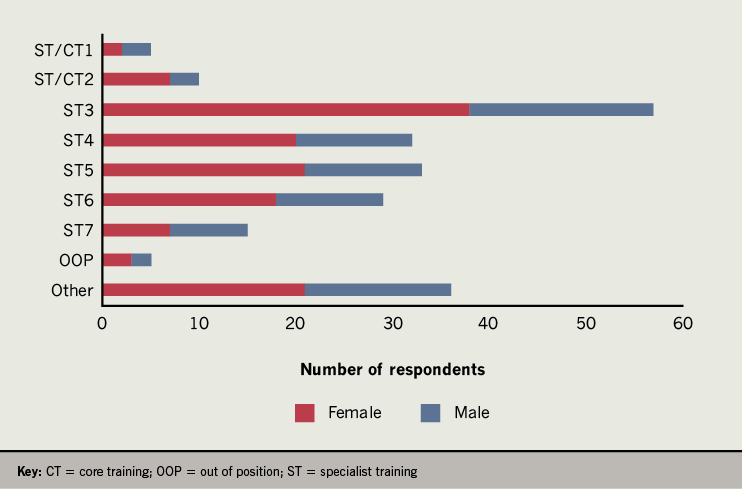

Current year of training ranged from specialty trainee (ST) year 1 to ST7 with 2% of respondents currently being out of programme (figure 1).

Of respondents, 41 were medical trainees: 18 care of the elderly (COTE), eight acute medicine, three diabetes and endocrinology, eight respiratory, and four gastroenterology. There were 63 general practice trainees. The remaining 116 were other specialties (anaesthetics, intensive care, surgery, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, psychiatry, radiology and emergency medicine). Seven of the survey respondents did not specify.

Less than full-time

Of trainees, 23.5% reported currently working less than full-time (LTFT) (n=52), all but two were female trainees (n=50). LTFT equivalent varied from 50–80%. When asked about working pattern, 26% stated they were supernumerary, 56% were working part-time in a full-time slot and 18% were in a job share.

Career decisions

Table 1. Reasons cited for a decision against training in cardiology

| Theme | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Not family friendly/work-life balance | 10 |

| Too competitive | 4 |

| Attitude of cardiologists | 4 |

| Lack of female role models | 3 |

| Perceived attitude of trainers towards female trainees | 3 |

| Bad experience as a junior doctor | 2 |

| Expectation of doing out-of-programme research | 2 |

Of respondents, 21% reported they had considered cardiology at some point in their training. Of these, 57% were women. When asked for the main reason that this was not pursued, 67% responded that they preferred another specialty. Other reasons are grouped into themes in table 1.

When asked what factors influenced their current choice of specialty, trainees reported work-life balance (41%), an enjoyable previous rotation (26%) and role models (11%) most frequently. Geographical location (5%), research opportunities (1.8%) and opportunity for private practice (1.8%) ranked bottom.

Previous cardiology exposure

Of participants, 49% had undertaken a cardiology placement at some point in their training. Of these placements, 44% had been during foundation years, 45% had been during core training and 11% were non-training posts. Tertiary centres were the venue for 33% of these posts; 66% were in a district general hospital.

Of participants, 52.6% who had rotated in cardiology reported their placement to be good or very good, while 19.3% reported it to be poor or very poor. District general hospital placements were more likely to be scored as good or very good than tertiary centre placements. Using a five-point score, with very good scoring five points and very poor scoring one point, the average score for a tertiary centre job was 3.0 and the average score for a district general hospital job was 3.7.

Bullying and sexism

We asked trainees whether they had experienced bullying or sexism during a cardiology placement. This question was answered a total of 152 times, the remaining 75 were left blank. From the responses available, when asked about bullying, 28% of trainees said they had witnessed and 13% reported they experienced bullying. Overall, 21% reported they had witnessed sexism and 11% reported they had experienced sexism.

When broken down by gender, bullying was witnessed by female trainees 27% of the time and experienced 14% (n=28 and 14, respectively). For male trainees this was reported as 24% witnessed and 14% experienced (n=12 and 7, respectively). When questions related to sexism are broken down by gender, female trainees witnessed and experienced sexism 24% (n=24) and 13% (n=13) of the time, respectively. In contrast, male trainees witnessed and experienced sexism 14% (n=7) and 0% of the time.

Perceived traits

Table 2. The main perceived traits of a cardiology registrar

| Major | Minor | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | Arrogant | 26 |

| Rude/abrupt/brusque | 20 | |

| Unapproachable | 19 | |

| Unhelpful | 11 | |

| Intimidating/standoffish | 7 | |

| Positive | Knowledgeable/intelligent/clever | 34 |

| Hard working | 21 | |

| Composed/calm under pressure | 18 | |

| Confident | 17 | |

| Focused | 15 | |

| Driven/ambitious | 11 | |

| General | Busy | 18 |

| Specialty focused/less interested in general medicine | 8 | |

| Type A | 5 | |

| Similar to surgeons | 4 | |

| Male | 3 |

Of respondents, 62% (n=133) felt cardiology consultants and registrars are perceived as unapproachable in the hospitals they have worked in. When asked if the perception of a specialty based on the main personality types it attracts impact on whether a trainee applies to said specialty, 85% of respondents said yes.

Trainees were asked what they felt were the main perceived personality traits of a cardiology registrar. Qualitative analysis was performed using an inductive content approach. Free-text responses were reviewed and grouped into major and minor themes. Responses were then reviewed and results collated as frequencies (table 2). Notable individual quotes are shown in table 3. Out of 161 responses, 66 contained no positive comments at all (41%).

Of participants, 160 (78%) felt that a basic introduction to specialist cardiology skills (including echocardiography, angiography and pacing) during core training would be a helpful insight into cardiology as a career.

Research

Of respondents, 10% (n=22) had already undertaken out-of-programme research (MD or PhD). Of those who had not, 24% (n=49) reported having plans to do a higher degree during training.

Comments

The questionnaire ended with an open box for general comments. Notable comments are shown in table 3.

Table 3. Notable quotes from a free-text question with regards to the perceived personality traits of a cardiology registrar and notable quotes from a free-text general comments question

| Notable Quotes – Perceived personality traits of a cardiology registrar |

|---|

| “Can often be rude and unhelpful to other specialties”

“I’ve also had difficulty getting them to come and see patients on ICU where other specialties can be more accommodating. That is a gross generalisation though, there are extremely helpful cardiologists too” “Lack of support to what they deem basic cardiology issues without insight that it may not be easy for others” “I have met some female cardiology registrars and they have been universally lovely, helpful and friendly” “Difficult to convince to see a patient – and that’s speaking registrar to registrar” All the cardiology registrars I have ever worked with have been approachable, diligent, happy to give cardiology advice, and supportive when doing GIM on calls” “There are many negative perceptions of cardiology registrars including rude, unprofessional, arrogant, too specialist, exclusive. I feel it’s unfair to make sweeping generalisations about a whole speciality – the majority of cardiology registrars I know are kind, polite, holistic and always willing to help” |

| Notable Quotes – General comments |

| “I really seriously considered cardiology at one point, but the attitude toward female trainees and the general bullying toward the registrars I worked with put me off: they never went home before 6:30 and all expected to have to take at least 3 years to do an MD/PhD”

“While sexism is not unique to cardiology as a specialty, it is more prevalent” “When I was in the tertiary centre, there were no female registrars so although I did not experience/witness any sexism, there was no one to be a victim of it” “I did a cardiology LAT post where the rota was 1 in 7 and a normal working day was 8 am to 7 pm. This was exhausting but was expected as the norm on a daily basis. For those with other commitments (children, caring, out-of-work activities) this working pattern is very difficult” |

Discussion

The number of female medical students and junior doctors has been steadily increasing over the past 10 years. Despite this, the proportion of females in cardiology has remained relatively static, making up just 13% of the consultant body.

Our survey demonstrates the perceptions of cardiology training as being in conflict with a healthy work-life balance for female and male trainees alike. The sacrifice is considered less appealing when combined with negative experiences of junior trainees during cardiology placements. This is in part related to bullying and sexism, which appear to be most prevalent in tertiary centres. Of our survey respondents, 28% reported being witness to bullying and 13% victims of bullying during a training cardiology placement, similar findings are also true for experiences of sexism. These findings echo the British Junior Cardiologists’ Association (BJCA) starter member survey in 2018, which looked at barriers to cardiology training in the UK. This survey was distributed to foundation doctors and core medical trainees. Of the 72 survey respondents (66% male), 24% reported bullying during a cardiology training post.8

The General Medical Council (GMC) survey of training in 2018 also identified that one in 20 junior doctors in training (5.8%, n=2,972) had experienced or been a victim of bullying in the workplace.9 These findings highlight that similar issues exist in other training programmes and specialties.

Furthermore, our survey demonstrates that, although there is no difference between reported bullying between genders, female trainees were at least twice as likely to witness or experience sexism. This is also likely to be an under-representation, as highlighted by one comment; “When I was in the tertiary centre, there were no female registrars so, although I did not experience/witness any sexism, there was no one to be a victim of it”. The American College of Cardiology third decennial Professional Life Survey completed by 2,313 cardiologists (including 964 women) found that two-thirds of women reported discrimination in the workplace.2 This was three times higher in female respondents.

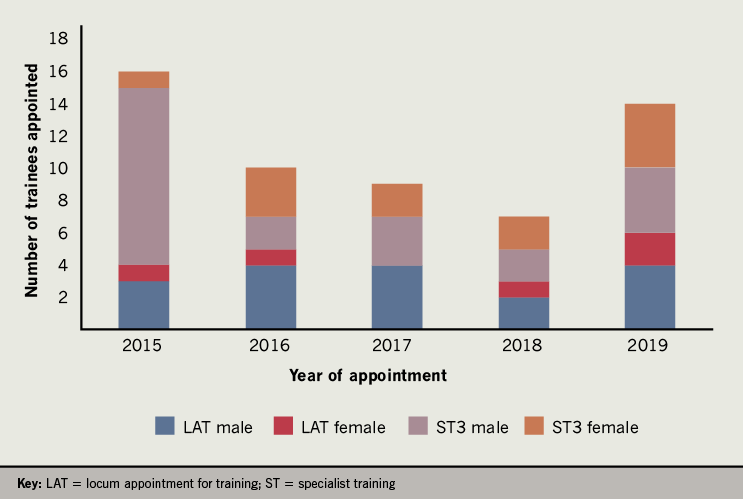

The majority of successful medical school applicants are now female.10 Despite efforts to recruit more women to cardiology, the number of applicants to cardiology in Wales had a 3:1 male to female ratio in the 2019 cohort. Despite this, there has been a rise in the number of females recruited to cardiology over the last five years in Wales, as demonstrated in figure 2. It is clearly important to address the barriers to women applying for this specialty in order to sustain the current trend in recruitment.

It has been hypothesised that there is a disparity in cardiovascular training between males and females that can be attributed to gender personality traits. Women are often perceived as having lack of self-esteem and a poor outward presentation of their skills in relation to their male counterparts.11 The latter may make it difficult to achieve gender parity in a male-dominated specialty that is still seen as an ‘old boys club’.1 This is a particular barrier to young trainees as having a positive role model was found to be the most valued professional development need for both men and women in multiple American surveys.12 It was also reported as the third most important factor relating to career decisions in our survey. The perception of women in the workplace has also been studied by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) women’s committee worldwide survey with similar observations.1

The BJCA starter survey reports that 78% of respondents were determined to pursue a career in cardiology.8 Clearly this is a sub-selected group. In our survey, 21% reported having considered cardiology at some point in their training. This may be considered a small proportion, however, considering 49% of respondents had completed a placement in cardiology we are evidently failing to inspire more than 50% to even consider it as a career option. Although negative experiences of cardiology placements and perceptions of the specialty not being holistic have all been highlighted as issues, there are other factors at play. The BJCA starter survey highlights concerns with regards to the current training structure. It has been reported that trainees approach higher specialist training feeling unprepared. This may make cardiology seem more daunting, as it entails the development of multiple new skills.

Currently, there is a slow but steady increase in the recruitment of women to cardiology. There is potential that over the next decade this will provide a more balanced workforce. However, a stark difference in the sub-specialty choices between genders still exists.13

Future initiatives addressing this will include the organisation of a Wales ‘Introduction to cardiology training day’ for foundation and internal medicine trainees with demonstrations of core cardiology skills including echo, pacing and cardiac catheterisation. For current cardiology trainees, surgical skills for cardiology workshops, as well as sessions on flexible working and returning to work after maternity leave, will be set up.

It must be highlighted that this survey is limited to assessing the perceptions and experiences of cardiology and does not study the culture in other specialties. There are likely to be parallel issues in other training programmes, which are beyond the scope of this work. Factors affecting career choice are dynamic. It would, therefore, be difficult to attribute a direct cause and effect of an alternative career choice directly on issues within the culture of cardiology, but our survey highlights important associations between the two that need to be addressed.

Conclusion

Women face multiple challenges to career advancement in cardiology, including concerns with regards to LTFT training, radiation exposure, lack of female role models and sexism. There have been many initiatives developed worldwide to try and address these issues including mentorship schemes and the introduction of a ‘Women in Cardiology’ session at national conferences including the British Cardiovascular Society annual meeting. Although women face particular barriers, cardiology specialist training is demanding for both male and female trainees.

Moving forward, cardiologists all have a responsibility to address the issues identified in this survey. Bullying and sexism, as well as rude and intimidating behaviour, must be addressed and judged as unacceptable. This sentiment has also been reiterated in a recent editorial published in the British Journal of Cardiology by Abel and colleagues.14 These issues are unlikely to be unique to cardiology as previous GMC survey results highlight, and it can be argued that initiatives to stop bullying and sexism should start at medical school during earlier formative years of training. Until this is achieved, we should be looking to correct deficiencies in our own culture first and foremost.

Despite a small survey size compared with other worldwide surveys, this is the largest to date in the UK that assesses perceptions of cardiology training, including others by the BJCA. The results of our survey have unearthed similar themes to other surveys created to address barriers facing women in Europe and America; highlighting that our results are not out of keeping with issues that face trainees worldwide. However, it is the first to explore opinions from those outside the specialty; asking non-cardiologists what barriers and deterrents they faced, and still face, with regards to cardiology training. Perceptions of the specialty as not being family friendly and competitive are almost predictable. However, despite the complex processes that determine career choice, the negative experiences of junior trainees in cardiology have proved one of the biggest deterrents from pursuing this as a career. When asked “why a career in cardiology was not pursued”; junior doctors cited the negative attitudes of cardiologists in the top three out of seven domains. Our attitudes and behaviours as cardiology consultants and registrars impact on junior trainees perhaps more than once thought; the question remains whether these can easily be changed.

Key messages

- Our survey is the first to investigate potential reasons why women choose alternative specialties to cardiology

- We found similar barriers to training as identified in other surveys including bullying and sexism

- Other significant barriers, not perhaps previously fully appreciated, include the negative experiences of junior trainees on cardiology placements, which is an important deterrent to training

- Career choice is a complex and dynamic process, but cardiology teams need to be mindful of their behaviours due to the implications this has for trainee retention and recruitment

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

Not required.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Robert McGowan from Health Education and Improvement Wales for support with distribution of the survey.

References

1. Capranzano P, Kunadian V, Mauri J et al. Motivations for and barriers to choosing an interventional cardiology career path: results from the EAPCI Women Committee worldwide survey. EuroIntervention 2016;12:53–9. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJY15M07_03

2. Lewis SJ, Mehta LS, Douglas PS et al. American College of Cardiology Women in Cardiology Leadership Council. Changes in the professional lives of cardiologists over 2 decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:452–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.027

3. Sarma AA, Nkonde-Price C, Gulati M et al. Cardiovascular medicine and society: the pregnant cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.978

4. Randhawa VK, Banks L, Rayner-Hartley E et al. Canadian women in cardiovascular medicine and science: moving toward parity. Can J Cardiol 2017;33:1339–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.010

5. Segan L, Vlachadis A. Women in cardiology in Australia – are we making any progress? Heart Lung Circ 2019;28:690–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2018.12.010

6. Curtis AB, Rodriguez F. Choosing a career in cardiology: where are the women? JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:691–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1286

7. Royal College of Physicians. 2016-2017 census (UK consultants and higher specialty trainees). London: RCP, 28 June 2017. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/2016-17-census-uk-consultants-and-higher-specialty-trainees

8. Yazdani MF, Kotronias RA, Joshi A et al. British cardiology training assessed. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2475–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz545

9. General Medical Council. Training environments 2018: key findings from the national training surveys. London: GMC, November 2018. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/training-environments-2018_pdf-76667101.pdf

10. Rogers AC, Wren SM, McNamara DA. Gender and specialty influences on personal and professional life among trainees. Ann Surg 2019;269:383–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002580

11. Capdeville M. Gender disparities in cardiovascular fellowship training among 3 specialties from 2007 to 2017. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019;33:604–20. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2018.10.030

12. Yong CM, Abnousi F, Rzeszut AK et al. Sex differences in the pursuit of interventional cardiology as a subspecialty among cardiovascular fellows-in-training. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:219–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.09.036

13. Sinclair HC, Joshi A, Allen C et al. Women in cardiology: the British Junior Cardiologists’ Association identifies challenges. Eur Heart J 2019;40:227–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy828

14. Abel A, Zakeri R, Hendry C, Clarke S. Women in cardiology: glass ceilings and lead-lined walls. Br J Cardiol 2019;26:125–7. https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2019.032