On the 31st March 2021, the German Health Ministry – on the advice of the Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) – declared that the Astra Zeneca/Oxford Vaxzevria vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), based on a chimpanzee adenovirus genetic scaffold, henceChAdOx1, would no longer be administered to those under the age of 60 years. In its hands were details of 31 cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) cases provided by the Paul Ehrlich Institute. These cases, of whom 19 had platelet deficiency, were seen after 2.7 million first and 767 second vaccine doses.

The German decision somewhat pre-empted the European Medicines Agency analysis published a week later on 7th April 2021 in which 62 cases of CVST and 24 cases of splanchnic vein thrombosis, 18 of which were fatal, had been reported via the EudraVigilance database. After considering the cases, the EMA responded:

“The benefits of the vaccine continue to outweigh the risks for people who receive it. The vaccine is effective at preventing COVID-19 and reducing hospitalisations and deaths”.1

By the date of the EMA report, 25 million people in the European Economic Area (EEA) and the UK had received the vaccine. Speculation at the time was that the condition resembled atypical heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and may have been induced by an auto-immune response triggered by the COVID-19 surface (spike) protein encoded in the vaccine.

Historical cases

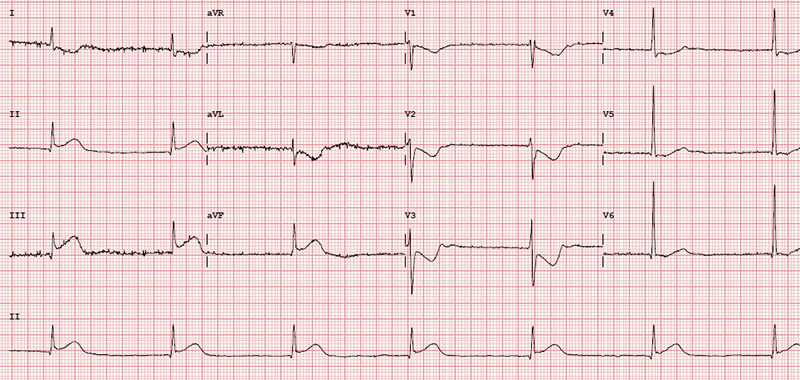

Cardiovascular effects by viruses are not new. Numerous cases of myocarditis were reported during the 1918 Spanish flu (influenza A, H1N1) pandemic, while cases of myo/pericarditis in influenza B patients were seen during the late 1950s. In 1980, cases of viral myocarditis following influenza infection were reported from a military hospital in Finland. Of the serologically confirmed influenza A patients, 9% had developed acute myocarditis based on serial ECG ST-segment and/or T-wave changes, unresponsive to beta blockade. Multidirectional echocardiography revealed regional myocardial dysfunction with elevated MB-CK levels in three patients.2 In 1997, a case of fatal myocarditis in a six-year-old female infected with influenza B was reported in New Orleans, USA. Post-mortem examination led to elimination of direct viral invasion of the myocardium or coronary vascular damage as potential causes, the authors concluding that an autoimmune mechanism was the most likely.3 Other cases have been seen with enterovirus B where IgM autoantibodies were elevated in patients with chronic myocarditis, triggering T cells into an autoreactive state, possibly by a mechanism of molecular mimicry.4 Examples of excessive coagulation were reported in a Dutch study in 2000 where several viruses, influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus and cytomegalovirus, on infection of human umbilical cord endothelial cells, induced procoagulant activity in a one-stage clotting assay causing a 55% reduction in the clotting time. This induction was associated with a four-to-five-fold increase in the expression of tissue factor as measured by the generation of factor Xa. The authors’ conclusion was:

“…the procoagulant activity of endothelial cells in response to infection with respiratory viruses is caused by upregulation of the extrinsic pathway”.5

COVID-19 era

While cardiovascular effects from infection with different respiratory viruses have been widely described over many decades, the incidence of such events during the largest pandemic since the Spanish ‘flu, and the rapidity with which clinicians, academics, and the public have become aware of such adverse effects through the media, has brought the behaviour of COVID-19 into sharp focus. Of particular concern has been the incidence of thrombotic events that seem to have been triggered not only by the virus itself but, worryingly, by certain COVID-19 vaccines, particularly those based on adenovirus vectors.

Hospitalised COVID-19 patients have been shown to develop both cardiac and kidney dysfunction, potentially mediated by the receptor for COVID-19 (the ACE-2 receptor), a protein that is widely expressed in many tissues, including the heart and kidney. Myocardial damage can occur as a result of:

- a decrease in oxygen levels

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- the formation of microthrombi (as has been observed in some COVID-19 patients)

- direct injury of cardiomyocytes by viral infection coupled with resulting inflammatory (cytokine) responses.

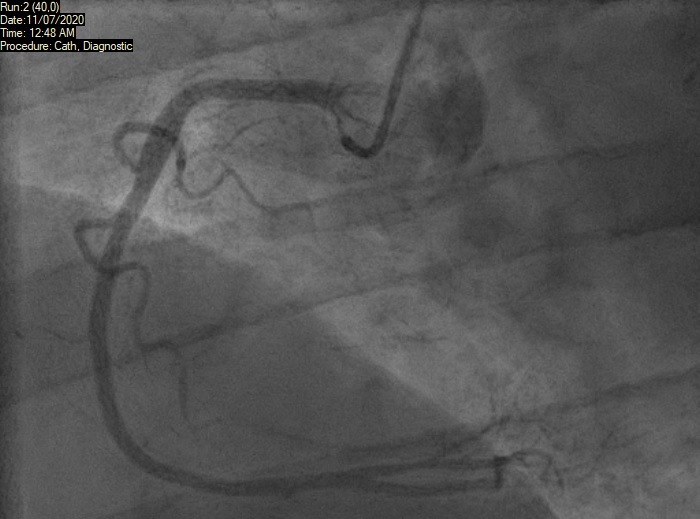

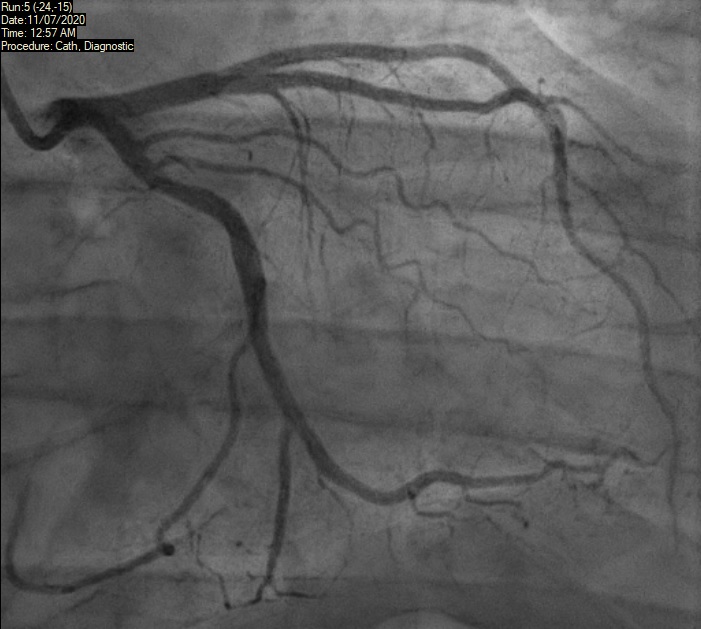

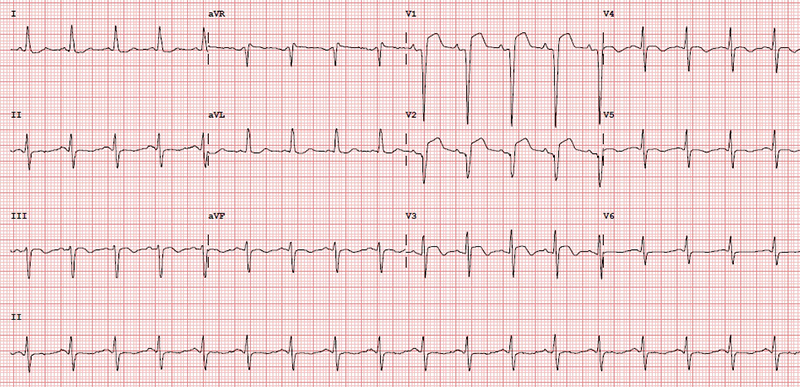

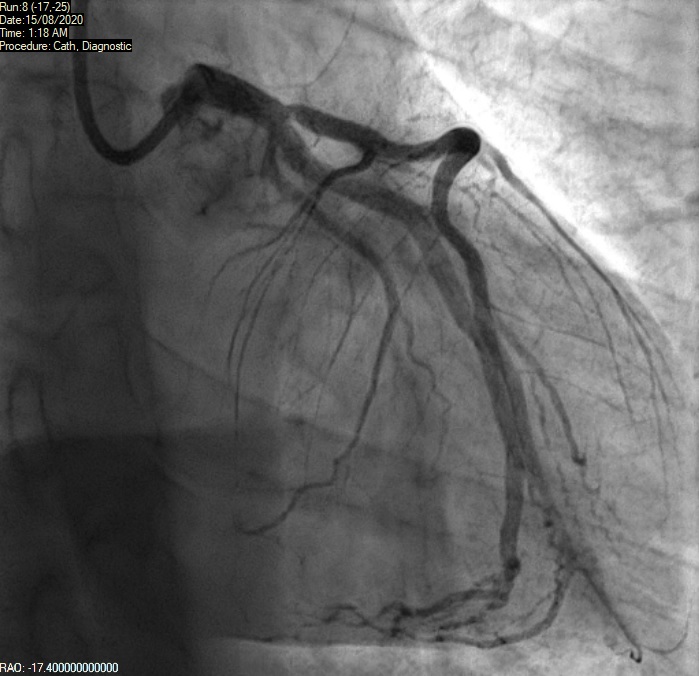

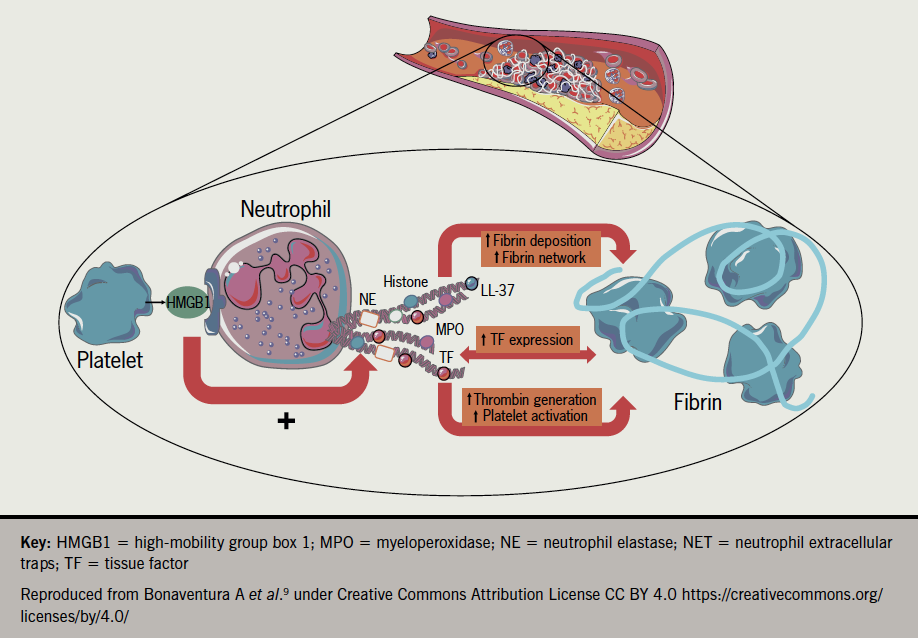

In vitro cardiomyocyte studies by Siddiq et al. suggest that direct injury from the infection is likely to be one of the causes of myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients.6 Raman et al.7 have proposed similar but subtly different aetiologies such as chronic inflammatory responses evoked by persistent viral reservoirs in the heart following the acute infection, or a mechanism where autoimmune responses to cardiac antigens are triggered through molecular mimicry, potentially explaining delayed damage. A further mechanistic candidate gathering interest has been proposed by Nappi et al. involving excessive activation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). It is well known that neutrophils are players in the first line of defence against bacterial and fungal infections but their involvement in response to viruses has only been described in recent years. In a process known as NETosis (resembling apoptosis) triggered by pathogen entry, neutrophils self-disintegrate releasing protein granules and decondensed chromatin which form net-like structures that can engulf (trap) pathogens, including viruses. Evidence from autopsy studies on patients who died from serious COVID-19 disease, and studies on patients who underwent primary coronary interventions for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), has implicated neutrophils and the resulting excessive production of aggregated NETs causing vascular-obstruction8 (figure 19).

The effects of the S-protein

While the exact mechanisms of cardiovascular damage from COVID-19 infection remain under study, with several candidate explanations, the story does not stop with the virus itself. Explanations of how COVID-19 vaccines can induce similar pathologies is of equal importance. The most extensively used vaccines are the mRNA vaccines of Pfizer (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) and the adenovirus-based (AdV) vaccines of AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1) and Johnson & Johnson (Ad26.COV2.S), all of which share the COVID-19 spike protein gene (RNA or DNA) but which differ markedly in the case of the AdV vaccines by the additional presence of AdV genes.

A critical observation has been the presence of the S-protein in the circulation post-vaccination, seen with both types of vaccine. Aside from its affinity for ACE-2 receptors present on many different organs, the S-protein, generated either by COVID-19 infection10 or from vaccination with the mRNA vaccine,11 has been shown to damage the endothelium, disrupt the blood-brain barrier, and/or cause inflammation and damage to human cardiac pericytes i.e. multi-functional mural cells of the microcirculation that wrap around the endothelial cells lining the capillaries throughout the body. A novel route of entry for the S-protein via the CD147 receptor has recently been implicated in the pericyte damage10 (CD147 is an extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer and is present on cardiac pericytes; it is also known as an entry receptor for measles virus).

A more extensive study of myocarditis based on reports to the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) exploring a possible causal relationship to the two mRNA vaccines, was carried out by the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and US medical centres, between December 2020 and August 2021. Out of more than 190 million people (median age of 21 years) with 354 million vaccinations, a total of 1,626 myocarditis cases were confirmed; an incidence rate of 8.6 per one million people. Of those affected and who reported their sex, 82% were males with the rates of myocarditis highest after the second vaccination. There was no difference in incidence for the two different mRNA vaccines. Of those aged under 30 years with detailed clinical information available, 87% had resolution of presenting symptoms by hospital discharge.12 Similar results were seen in a smaller 26-centre US study published in February this year.13 In a more recent analysis of Israeli army recruits who had received a third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine, the incidence of myocarditis was lower than after the second dose, a result unexplained and requiring “future research”.14

The incidence of CVST

If science was easy everyone would be doing it. In a recently published meta-analysis in the Journal of Neurology, the authors stated that vector-based (e.g. ChAdOx1 or Ad26.COV2.S) COVID-19 vaccination was associated with an approximately 50-fold increase in the odds of thrombotic thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS)-related CVST compared to non-TTS-related CVST. They also note that antigenic complexes of vaccine components have been shown to bind to platelet factor 4 (PF4) on platelet surfaces, inducing proinflammatory reactions, anti-PF4 antibody formation and prothrombotic cascades.15 The possibility that anti-PF4 antibodies form as a result of epitope mimicry with the COVID-19 S-protein has been previously proposed. So far, however, other studies on anti-PF4 antibodies found in patients have shown no binding of these antibodies to the viral S-protein.16 What is clear though is that in the rare cases of vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), associated with both the AD26.COV2.S and ChAdOx1 vaccines, anti-PF4 antibodies are not only present but in a recent study have been shown to persist for several months after acute presentation. Key to this observation by Kanack et al. was development of a diagnostic assay able to distinguish VITT from spontaneous HIT, another rare anti-PF4-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic disorder.17

In a related UK study, carried out between December 2020 and June 2021 on a combined cohort of approximately 11.6 million people with a 6.8 million person years follow-up, the authors found a ‘small elevated risk’ of CVST events following vaccination with ChAdOx1 but not with BNT162b2.18 To confuse matters further, a large US study took the step of comparing the incidence of CVST in COVID-19 vaccinated cohorts and those who had received other non-COVID vaccines during the four-year period 2017–2021. The conclusion of this study, which used databases from the US Mayo Clinic Health System, was:

“This real-world evidence-based study finds that CVST is rare and is not significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccination…”

“…the risk of CVST within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccination was similar to the risk of CVST within 30 days of all analysed non-COVID vaccinations…”19

Conclusion

The frustration that must be present among clinicians and virologists alike is palpable. There is no question that serious (thrombotic) and frequently recoverable (myocarditis) cardiovascular events occur both after COVID-19 infection and after vaccination, but they are rare. Further, when the incidence of such events is compared with other vaccinations, the picture of an elevated COVID-19 cardiovascular pathology causally related to vaccination is not well defined. Until then, the clinical communities eagerly await the mechanistic breakthroughs that will define effective therapies for these important pathologies.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Editors’ note

Anthony R Rees is the author of recent book A new history of vaccines for infectious diseases available from Elsevier/Academic Press (ISBN 978-0-12-812754-4).

References

1. European Medicines Agency. News release 7th April 2021. AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/astrazenecas-covid-19-vaccine-ema-finds-possible-link-very-rare-cases-unusual-blood-clots-low-blood (last accessed 4th May 2022)

2. Karjalainen J, Nieminen MS, Heikkilä J. Influenza A myocarditis in conscripts. Acta Med Scand 1980;207:27–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0954-6820.1980.tb09670.x

3. Craver R, Sorrells K, Gohd R. Myocarditis with influenza B infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16:629–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199706000-00018

4. Hussein HM, Rahal EA. The role of viral infections in the development of autoimmune diseases. Crit Rev Microbiol 2019;45:394–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2019.1614904

5. Visseren FL, Bouwman JJ, Bouter KP, Diepersloot RJ, de Groot PH, Erkelens DW. Procoagulant activity of endothelial cells after infection with respiratory viruses. Thromb Haemost 2000;84:319–24

6. Siddiq MM, Chan AT, Miorin L et al. Functional effects of cardiomyocyte Injury in COVID-19. J Virol 2022;96(2):e01063-21. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01063-21

7. Raman B, Bluemke DA, Lüscher TF, Neubauer S. Long COVID: post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 with a cardiovascular focus. Eur Heart J 2022;43:1157–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac031

8. Nappi F, Giacinto O, Eliouse O et al. Association between COVID-19 diagnosis and coronary artery thrombosis: a narrative review. biomedicines 2022;10:702. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10030702

9. Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Abbate A, Montecucco F. Neutrophil extracellular traps and cardiovascular diseases: an update. Cells 2020;9:231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9010231

10. Avolio E, Carrabba M, Milligan R et al. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein disrupts human cardiac pericytes function through CD147 receptor-mediated signalling: a potential non-infective mechanism of COVID-19 microvascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2021;135:2667–89. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20210735

11. Singh A, Nguyen L, Everest S, Afzal S, Shim A. Acute pericarditis post mRNA-1273 COVID vaccine booster. Cureus 2021;14(2):e22148. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22148

12. Oster ME, Shay DK, Su JR et al. Myocarditis cases reported after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination in the US from December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA 2022;327:331–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.24110

13. Truong DT, Dionne A, Muniz JC et al. Clinically suspected myocarditis temporally related to COVID-19 vaccination in adolescents and young adults: suspected myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination. Circulation 2022;145:345–56. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056583

14. Friedensohn L, Levin D, Fadlon-Derai M et al. Myocarditis following a third BNT162b2 vaccination dose in military recruits in Israel. JAMA 2022;327:1611–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.4425

15. Palaiodimou L, Stefanou M-I, Aguiar de Sousa D, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the setting of COVID‑19 vaccination: a systematic review and meta‑analysis. J Neurol 2022:April 8:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11101-2

16. Rees AR. A new history of vaccines for infectious diseases. London: Elsevier/Academic Press, 2022. Chapter 14, Immmunological challenges of the ‘new’ infections: corona viruses; p. 395–450.

17. Kanack AJ, Bandana S, George G, et al. Persistence of Ad26.COV2.S-associated vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) and specific detection of VITT antibodies. Am J Hematol 2022;97:519–26 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26488

18. Kerr S, Joy M, Torabbi F et al. First dose ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccinations and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: A pooled self-controlled case series study of 11.6 million individuals in England, Scotland, and Wales PLoS Med 2022;19(2):e1003927. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003927

19. Pawlowski C, Rincón-Hekking J, Awasthi S, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is not significantly linked to COVID-19 vaccines or non-COVID vaccines in a large multi-state health system. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2021;30(10):105923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105923