Heart failure (HF) is increasingly common and incurs a substantial cost, both in terms of quality and length of life, but also in terms of societal and economic impact. While significant gains are being made in the therapeutic management of HF, we continue to diagnose most patients when they are acutely unwell in hospital, often with advanced disease.

This article presents our experience in working collaboratively with primary care colleagues to redesign our HF pathway with the aim of facilitating earlier, community, diagnosis of HF. In so doing, and, thus, starting prognostic therapy much earlier in the course of the disease, we seek to avoid both the cost of emergency hospitalisation and the cost of poorer outcomes.

Introduction

When COVID-19 struck, changing not only how we work as clinicians, but how patients wish their care to be managed, it provided the necessary impetus to undertake such transformation work. During the pandemic an estimated 23,000 diagnoses of heart failure (HF) were missed with an associated 44% drop in referrals for diagnostic echocardiography compared with 2019.1 During a six-week period of the second wave, another study found that there was a 41% decline in HF-related admissions and a 34% decline in heart attack admissions.2 Such reductions in admissions were seen during the first wave and were noted to contribute to more than 2,000 excess deaths during the pandemic peak in England and Wales.

Even before COVID-19, there had long been interest in transforming HF pathways in order to facilitate earlier diagnosis of this life-limiting and eminently treatable disease. We know that many patients are symptomatic for years prior to a diagnosis with HF, which occurs most often in hospital as opposed to in the community,3 and that such a ‘late’ diagnosis incurs significant costs, not only economic but societal too. While there has been some enthusiasm in transforming digital pathways to aid this, there lacked engagement from clinicians to undertake such service redesign.

The dual challenge of a growing HF burden and limited resources to manage this, have driven innovation and collaboration to enhance and improve existing pathways. We describe below our experience of transforming our local HF pathways.

Rationale for creating an ‘ideal’ HF pathway

In principle, most HF pathways are quite straightforward and are based on National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines – if there are symptoms and signs of HF, together with elevated natriuretic peptides, a GP can refer a patient for diagnostic echo and specialist review. However, HF is frequently comorbid and, even when it is not, symptoms can be missed if the diagnosis is not considered. Once considered, a GP needs to know, not only which tests to organise, but also how to do so within their constantly changing IT pathways. They then need to interpret the results based on the patient presentation and action these appropriately. As such, communication between specialist HF teams and primary care needs to be robust and clear, without additional unnecessary information and paperwork that can leave further requests and actions muddied. Coding is likewise essential for a number of reasons, not only to confirm quality and effectiveness, but also to ensure that patients have accurate medical records and are being treated and flagged appropriately. IT links with allied community teams tend to be obtuse, and pathways for advanced care planning, likewise, clunky. This all leads to multiple teams working disparately to treat the same patient.

An ideal HF pathway might, therefore, be expected to rely on sound clinical knowledge, signposting, communication, coding, IT literacy, and integration and joint working. Development of such a pathway requires involvement from all, including primary care, HF specialists, patients, IT and administrative input. In order to transform services, a project management team is essential to facilitate change, supporting and bringing together already overburdened clinical services; this is a resource rarely afforded to clinical teams.

Creating an integrated HF pathway in North West London

We focused our transformation work in one North West London (NWL) borough, concentrating initially on outcome measures for the pathways already in place, as well as the difficulties clinicians had in providing care. This area benefits already from a fully integrated HF service, with one named HF consultant and three Heart Failure Specialist Nurses (HFSNs), covering both the acute Trust and community HF services. The HF pathway was (and remains) a straightforward NICE-appropriate referral algorithm with specialist triage. The pathway benefits from using the same IT system with full interoperability within the community HF service and primary care – SystmOne (S1).

We found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that this borough faces many of the same challenges as the wider National Health Service (NHS): some HF referrals are not considered appropriate due to lack of relevant diagnostics and/or information (thus incurring delay), two-thirds of patients are diagnosed with HF in the acute setting as compared with the community, and only about 20% of HF patients, when compared with the expected prevalence for the area, had been seen by specialist HF services, likely due to poor coding. In addition, we estimated that up to 60% of HFSN time could be classified as administrative – nurses spent considerable time triaging inappropriate referrals due to lack of understanding, clarity of referral criteria and forms that were labour intensive to complete. The nursing templates on S1 did not integrate sufficiently with GP records and, thus, were not able to contribute to the generation of correct coding or appropriate documentation to support GPs, particularly on discharge for onward management. Lastly, the ability to refer to other community services via S1 was not available, and nurses had to refer outside of the patient record, not only increasing the administrative burden but creating potential risk of duplication and incorrect patient records.

In order to address these issues, a team was formed to map and then redesign the HF pathway from end to end. Two primary care physicians, one HF consultant and one HFSN were joined in weekly meetings by a project management team supported by Discover-NOW, the health research data hub led by Imperial College Health Partners.4 The ambition was to improve outcomes for HF patients by creating long-term, sustainable changes to the care pathway through the following objectives:

- The creation of a truly integrated HF pathway across primary and secondary care.

- Improvement of community HF referral rates and ensuring relevant data available.

- Reduction of non-elective HF admissions to secondary care.

- Improved efficiency of the HF services (maximising clinicians’ time).

- Improved HF patient experience and outcomes.

- Development of a novel and transferable approach for transforming other HF pathways.

Fundamental to this change was the need to bridge the divide between primary and secondary care – such integrated working was the only way to understand the patient journey from multiple perspectives. In addition to the core team, we also interviewed over 20 clinicians involved in the patient journey, including GPs, cardiologists, HFSNs, pharmacists, rapid response teams, district nurses and community matrons. Importantly, patient users were consulted on their experiences and areas for potential improvement. Using design-thinking methodology (whereby users are central to developing and creating ideas for transformation), a blueprint end-to-end pathway spanning first appointment with potential symptoms with the GP to end-of-life care was produced. This provided a valuable starting reference of what the patient journey might look like – of significance; this was the first time that all members of the team had a full perspective of all parts of the patient journey.

Demonstrating the cumulative impact of marginal gains in pathway transformation

We realised early on during this process that the original pathway was, in general, built on a sound premise. However, there were specific points that did not work as well as hoped and, although these issues were relatively minor, when added together, it became apparent that these amounted to significant breakdowns at various points in the pathway. We, therefore, chose to focus on the cumulative impact of making many small changes (marginal gains) to transform the pathway with the aim of making it more cohesive, clear and efficient.

Identifying opportunities

Table 1. Key pathway interventions

| Organisational change |

|---|

| Improved communication channels between primary and secondary care – assigning HFSNs to PCNs |

| Increased involvement and role of pharmacists |

| Developed measurement frameworks to assess the ongoing impact of the changes made |

| SystmOne |

| New GP-specific referral template |

| Two new HF care plan templates – HFSNs and GPs |

| Four new clinic letters – GP referral, initial assessment, follow-up appointment and discharge letters |

| Redesigned HFSN templates with over 100 modifications |

| Integrated Coordinate My Care for advanced care planning |

| Technology |

| Implemented remote patient monitoring and uptitration technology/app |

| Over 25 HF education modules created for patients within the app |

| Digital version of HF and Patient Activation Measure questionnaires for patients to complete on tablet devices |

| Communication |

| Provided HFSN training to use new remote monitoring system |

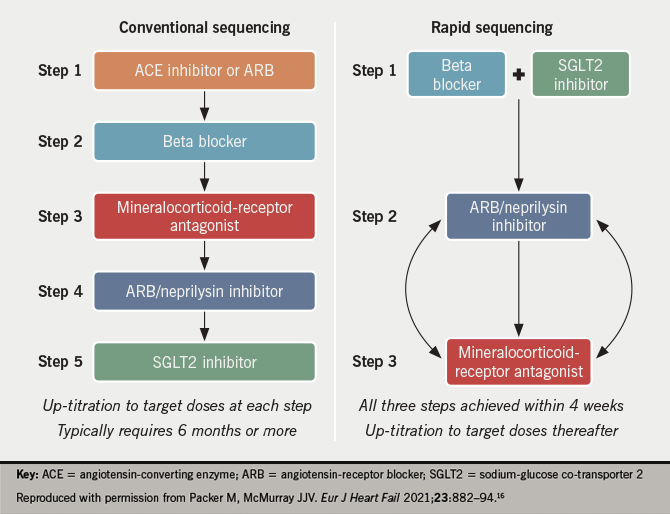

| GP education webinar delivered to ~100 North West London GPs, including guidance on SGLT2 inhibitors |

| GP monthly virtual advice, guidance and education |

| Created comms assets to share our project achievements |

| Key: GP = general practitioner; HF = heart failure; HFSN = heart failure specialist nurse; PCN = primary care network; SGLT2 = sodium-glucose transport protein 2 |

With a forensic review of the pathway, the team initially identified over 30 such marginal gains opportunities across the HF pathway, with more identified as the project progressed. These were prioritised as either key opportunities and/or quick wins to deliver in 2020 to 2021, and were often dependent on the existing infrastructure, such as clinical systems, ordering mechanisms, and other community providers. Core categories of change are highlighted in table 1.

Specific examples of changes undertaken include:

- Generating new care plan templates that were more focused towards the information a busy GP needs to be aware of, separating this from the care plan that is sent to the patient.

- HFSN clinic templates were changed to make administrative duties more efficient and save time by allowing easier recording of clinical history and a smooth flow of information from the GP clinical system.

- The cardiology team are now able to make direct referrals to the various community services without the need for the GP. To enable this, quick links in S1 now exist to enable referral to community services (district nurses, community matrons, etc.) without needing to go outside the patient record.

- Weekly online educational sessions are held, which include time for GP advice and guidance, and which have helped improve relationships between colleagues.

- N-terminal pro-brain naturietic peptide (NT-proBNP) is now part of a ‘shortness of breath’ panel of tests that GPs can request, with BNP removed as an option. There is now guidance on use, and how to interpret the results, within S1/electronic patient record (EPR).

- A one-page referral proforma to secondary care now replaces the eight-page earlier version.

- A named nurse per primary care network (PCN) to help build relationships and collaboration. Offering education to all members of the primary care team and assisting with register reviews.

Interim data have shown clear benefits of having made many small changes to the pathway. We have seen a 7% indicative, appropriate, increase in referrals to the HF service; more than 300 new HF patient records have been created in six weeks using the new GP template; there have been over 100 newly coded HF patients per month since the launch of new templates. Lastly, we have also seen a 70% reduction in incorrect blood test requests, and we estimate 40 minutes per week in time saved for cardiologists from the new referral process. Data analysis is ongoing and further review at six months and one year expected. It is anticipated that such changes, as highlighted above, will lead to a significant cost reduction in HF spend, alongside a decrease in morbidity and mortality, relating to earlier and improved rates of diagnosis, these being more often undertaken in the community.

What’s next?

The blueprint of the HF pathway created by our team will work effectively for the next 12 months, but we have visualised more innovative and ambitious ideas for a future pathway within three to five years, in part based on current active research projects, which necessarily include technological and digital advances. However, this paper seeks to emphasise how success can result from building relationships across primary and secondary care – breaking down silo working and thinking – to uncover and ease previously unknown challenges from each side. This is the NHS working envisaged by patients, and which we, and many others, feel is necessary to tackle the increasing inequity and strain on our services.

Key messages

- With growing burden of HF we must find innovative ways to utilise existing resources

- Collaboration and integration across care settings is key to success in transforming and improving existing pathways

- Marginal gains can lead to significant improvement

Conflicts of interest

CB has received educational honoraria from ViforPharma, Novartis, AstraZeneca and Alnylam; CMP has received educational honoraria from ViforPharma, Novartis and Medtronic; SG and AS: none declared.

Funding

The project management team were funded by AstraZeneca as part of the DiscoverNOW consortium.

Study approval

None required.

Acknowledgements

Jon Stephens, Hanna Pang, Lizzie Shupak, Ross Stone, Katrina Mullin and Manish Chatterjee, AstraZeneca UK.

References

1. Patel P, Thomas C, Quilter-Pinner H. Without skipping a beat. The case for better cardiovascular care after coronavirus. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, March 2021. Available from: https://www.ippr.org/files/2021-03/without-skipping-a-beat.pdf [accessed 14 June 2021].

2. Wu J, Mamas MA, Belder MA, Deanfield JE, Gale CP. Second decline in admissions with heart failure and myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1141–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.039

3. Bottle A, Kim D, Aylin P, Cowie MR, Majeed A, Hayhoe B. Routes to diagnosis of heart failure: observational study using linked data in England. Heart 2018;104:600–05. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312183

4. Imperial College Health Partners. Discover-NOW. Health data research hub for real world evidence. Available at: https://imperialcollegehealthpartners.com/discover-now/