Hypertension affects over a billion people worldwide and is a leading cause of premature death and disability. However, it continues to remain a silent epidemic, with the majority of patients undiagnosed or untreated. The World Health Organisation reports that only 42% of individuals with hypertension receive a diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Furthermore, only one in five adults have their blood pressure under control.1 These statistics reflect a grave failure in identifying and managing a condition that has far-reaching health consequences. The misdiagnosis and undertreatment of blood pressure pose substantial risks to individuals and impose a tremendous burden on healthcare systems worldwide.

Measurement

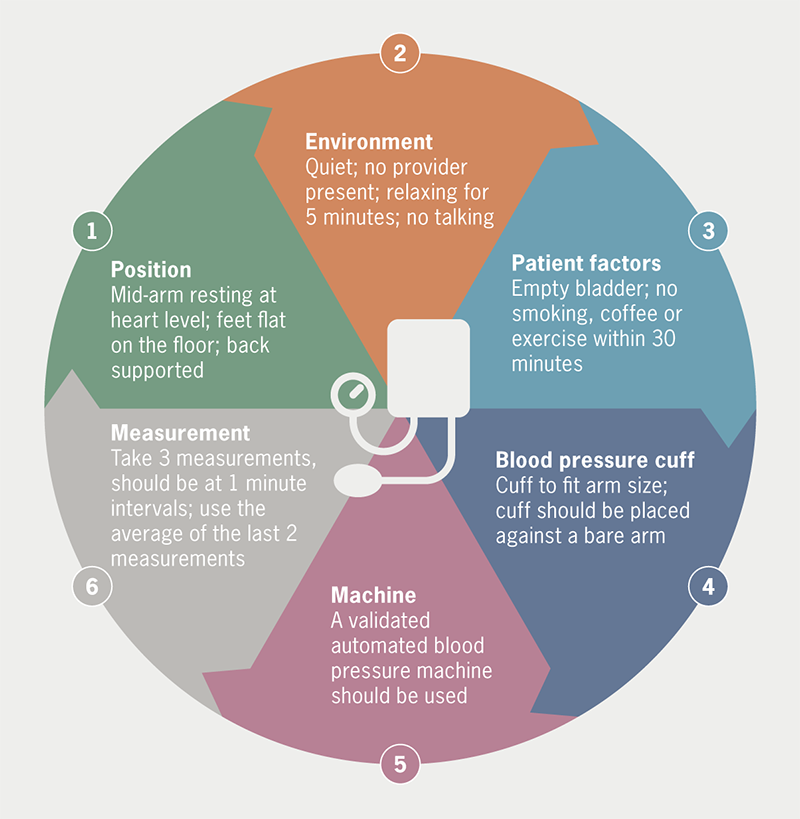

Blood pressure measurement is a quintessential part of healthcare, and accurate measurement is paramount for proper diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. However, studies indicate that inaccuracies in blood pressure monitoring are prevalent, even among healthcare professionals.2–5 Flawed measurement techniques, such as relying on a single reading, insufficient time for measurement, and incorrect arm positioning contribute to misdiagnoses.

Our prior work has highlighted the inadequate adherence to accurate blood pressure measurement protocols among healthcare professionals, including even cardiologists.2 Key factors contributing to inaccuracies included failure to measure blood pressure in both arms, insufficient time before measurement, and reliance on a single reading. Other contributors to inaccuracies were a preference for measurements ending in zero, which accounted for 60–80% of readings, improper positioning of the arm in relation to the heart, and patient-related factors, such as crossing the legs, making measurements over long-sleeve clothing, or addressing the need to urinate prior to the blood pressure measurement. What is even more concerning was that, despite these inaccuracies in measurement, eight of every 10 healthcare professionals trusted their blood pressure measurements, indicating a significant disconnect between accurate measurement and perceived accuracy. Opinions varied among medical assistants, nurses, and doctors regarding the need and frequency of practising blood pressure measurement skills, and they had differing knowledge about the reliability of their blood pressure measurement equipment to ensure accuracy.

Where does this leave the effort to combat hypertension?

Do the inaccuracies of in-office blood pressure measurement emphasise the need for better education and training among healthcare professionals, or is it time to shift gears towards out-of-office blood pressure assessment? The answer is likely yes to both. Out-of-office blood pressure assessment involves home blood pressure measurement and ambulatory blood pressure measurement, both of which are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Society of Hypertension (ESH), and the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines as complementary methods for measuring blood pressure and diagnosing hypertension.6–8 Although each method comes with its own disadvantages, including the potential for measurement error, both home and ambulatory blood pressure measurements can diagnose white-coat and masked hypertension. Furthermore, these modalities better prognosticate future cardiovascular events compared with office measurement of blood pressure.9,10

While out-of-office methods will likely alleviate some of the misdiagnoses of hypertension, healthcare professionals must adhere to the most recent blood pressure measurement guidelines.6–8 These guidelines recommend the use of validated automated devices, regular calibration, measurements taken in both arms, and the recording of multiple readings with proper intervals. Graphical recording of blood pressure values within ranges can help reduce the impact of inaccuracies.3 Physicians should consider using automated office blood pressure (AOBP) readings as the preferred method for routine blood pressure monitoring to ensure accurate measurements and reduce the potential impact of the white-coat effect. AOBP readings, taken with the patient sitting alone in a quiet place, are similar in accuracy to ambulatory readings and more accurate than routine office readings.11

What can be done?

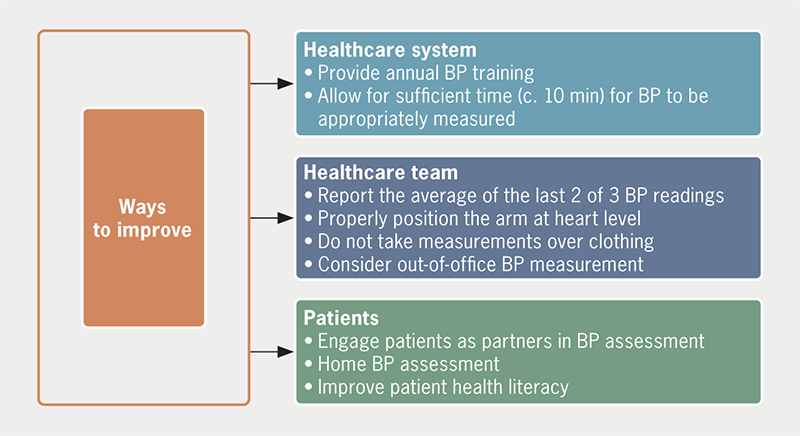

Combatting blood pressure misdiagnosis, clinical inertia and undertreatment require a collaborative effort between healthcare professionals, patients, and emerging technology (figure 1). Patient education plays a crucial role, ensuring individuals understand the importance of accurate measurements, the risks associated with hypertension, and the significance of treatment adherence (figure 2). Similarly, additional physician and healthcare professional education is clearly required. Standardised blood pressure management protocols should be implemented, and clinic personnel should be trained, and preferably certified, in standardised blood pressure measurement, and receive regular refresher training.12 Healthcare systems must allocate resources to establish preventive care programmes, integrate routine blood pressure screenings into regular check-ups, and launch community-based initiatives for early detection.13–16 Leveraging technological advancements, such as telemedicine and mobile health applications, can further enhance accuracy and patient engagement.17,18

The delusion and inaccuracies surrounding blood pressure measurement undermines the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, leading to significant health risks and economic burdens. By promoting accurate measurement techniques, enhancing patient education, and fostering collaboration among healthcare professionals and policymakers, we can bridge the gap in blood pressure management. Improving diagnostic accuracy and treatment adherence will not only save lives but also reduce healthcare costs and alleviate the burden on healthcare systems, fostering a healthier future for all.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

1. World Health Organization. Hypertension. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension#:~:text=An%20estimated%2046%25%20of%20adults%20with%20hypertension%20are,adults%20%2821%25%29%20with%20hypertension%20have%20it%20under%20control [accessed 19 May 2023].

2. Gulati M, Peterson LA, Mihailidou A. Assessment of blood pressure skills and belief in clinical readings. Am J Prev Cardiol 2021;8:100280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100280

3. Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, Ward HE, Watson MO. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of adult patients’ resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens 2017;35:421–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001197

4. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, Haller DM, Bovier P. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens 2014;32:509–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000058

5. Sandoya-Olivera E, Ferreira-Umpiérrez A, Machado-González F. Quality of blood pressure measurement in community health centres. Calidad de la medida de la presión arterial en centros de salud comunitarios. Enferm Clin 2017;27:294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2017.02.001

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NG136. London: NICE, 2019. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/chapter/recommendations

7. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 2018;36:1953–2041. [Published correction appears in J Hypertens 2019;37:226.] https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940

8. Flack JM, Adekola B. Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2020;30:160–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2019.05.003

9. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, Heneghan C. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens 2012;30:449–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834e4aed

10. Fagard RH, Celis H, Thijs L et al. Daytime and nighttime blood pressure as predictors of death and cause-specific cardiovascular events in hypertension. Hypertension 2008;51:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100727

11. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:351–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

12. Woods JL, Jacobs MD, Sheeder JL. Improving blood pressure accuracy in the outpatient adolescent setting. Pediatr Qual Saf 2021;6:e416. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000416

13. Rossi GP, Bisogni V, Rossitto G et al. Practice recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of the most common forms of secondary hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2020;27:547–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-020-00415-9

14. Severin R, Sabbahi A, Albarrati A, Phillips SA, Arena S. Blood pressure screening by outpatient physical therapists: a call to action and clinical recommendations. Phys Ther 2020;100:1008–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa034

15. Zhou Q, Yu M, Jin M, Zhang P, Qin G, Yao Y. Impact of free hypertension pharmacy program and social distancing policy on stroke: a longitudinal study. Front Public Health 2023;11:1142299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1142299

16. Valdés González Y, Campbell NRC, Pons Barrera E et al. Implementation of a community-based hypertension control program in Matanzas, Cuba. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:142–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13814

17. Omboni S, McManus RJ, Bosworth HB et al. Evidence and recommendations on the use of telemedicine for the management of arterial hypertension: an international expert position paper. Hypertension 2020;76:1368–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15873

18. Mabeza RMS, Maynard K, Tarn DM. Influence of synchronous primary care telemedicine versus in-person visits on diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Prim Care 2022;23:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01662-6