Digoxin has been used in the management of chronic heart failure (HF) and atrial fibrillation (AF) for over 250 years. It is the only drug that combines an inotropic effect with a reduction in ventricular rate in AF. Therefore, in theory it should be an ideal treatment for HF, especially when there is co-existent AF. However, due to concerns about arrhythmia and toxicity, its use has declined dramatically over recent decades.

In the only large, randomised trial of patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), digoxin demonstrated a reduction in hospitalisation with no adverse effect on total mortality but patients in AF were excluded. In patients with both AF and mild HF (mainly HF with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF]), the much smaller RATE-AF (Rate Control Therapy Evaluation in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation) trial showed that in comparison to a beta blocker, digoxin did not differ in its impact on quality of life and heart rate control but had superior effects on symptoms, N-terminal of the prohormone of B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and treatment-related adverse events. Meta-analysis also indicates that for patients with HF and AF, digoxin does not cause excess mortality; previous indications of mortality were almost certainly explained by prescription bias in non-randomised trials.

It appears that digoxin is far from being redundant and might be the treatment of choice for older patients with AF and stable mild HF. It may also reduce the need for admission in patients with HFrEF without AF. As meta-analysis suggests that beta blockers may not confer prognostic benefit in patients with AF and HFrEF, it is also a reasonable choice in this group to achieve rate control.

Introduction

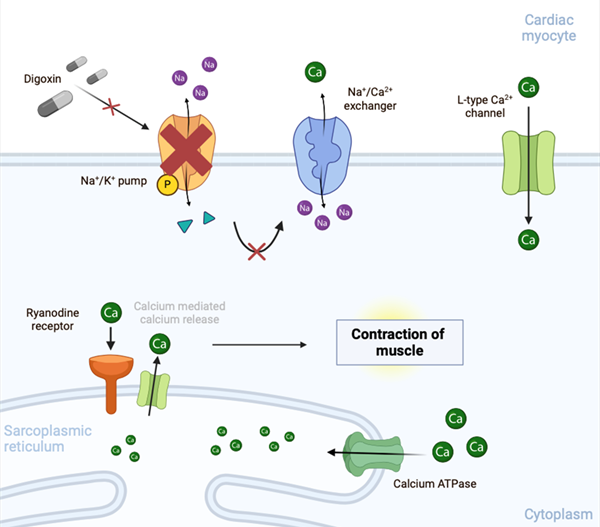

Following its discovery and introduction for clinical use in Birmingham, UK almost 250 years ago, digoxin has been used for the treatment of heart failure (HF). Indeed, until the advent of diuretics in the 1950s, it was the only available drug for this condition.1 Digoxin is an unusual drug in many respects. Derived from the foxglove plant, it increases intracellular Ca2+, and as an oral inotrope, is the only drug for chronic use in HF that addresses the primary problem, namely reduced cardiac pumping capacity (figure 1). All the other commonly used drugs for HF act indirectly to either inhibit the adverse neurohormonal responses or (in the case of diuretics and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 [SGLT2] inhibitors) to reduce Na+ and water retention by the kidney. In the early twentieth century, digoxin was found to also reduce the ventricular rate in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), probably as a result of increased cardiac vagal activity. It remains a treatment option for a ‘rate control’ strategy, although beta blockers and calcium-channel blockers are now more commonly used for this indication.

| Key: ATPase = adenosine triphosphatase |

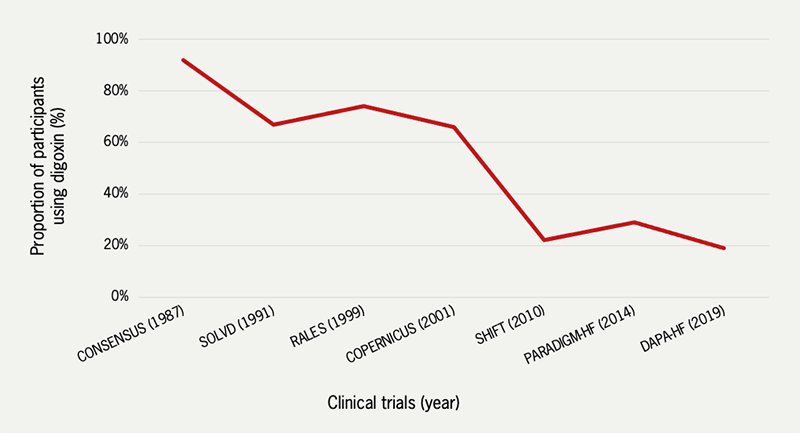

It is the positive inotropic action of digoxin that has led to a high degree of suspicion that, like all other inotropic drugs, it increases the risk of lethal arrhythmia. Small observational studies in the 1980s raised concerns about possible adverse effects on mortality2 and the MADIT-CRT (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy) reported a higher risk of ventricular arrhythmia in patients receiving digoxin.3 This concern, combined with its narrow therapeutic index, reports of toxicity, and of course, the advent of other effective drugs has led to the dramatic reduction in digoxin use for both HF and AF. Between 1997 and 2012, digoxin use in the USA fell by nearly 90%. In the UK, its use has also declined markedly, although it is still used in about 18% of cases of HF.4,5 This is also reflected in clinical trials of HF treatment where the number of patients taking digoxin at baseline has declined in recent years (figure 2).6

| Key: CONSENSUS = Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study; COPERNICUS = Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival; DAPA-HF = Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure; PARADIGM-HF = Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition versus Enalapril in Heart Failure; RALES = Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study; SOLVD = Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction Graph created by the authors from data obtained from relevant published trial results |

The waning enthusiasm for the use of digoxin by cardiologists has been challenged by evidence from randomised trials, namely the Digoxin Investigators Group (DIG) trial published in 1997 and the RATE-AF trial published in 2020.7,8 and by meta-analysis of digoxin trials.6 These trials suggest that there may yet be a place for digoxin in the treatment of both HF and AF, despite the published suggestion that ‘it’s time to leave the foxglove in the garden and in the history books—and out of the medicine cabinet.’9

HF and AF – the scope of the problem

Chronic HF is a syndrome resulting from cardiac functional or structural abnormalities that cause a reduced cardiac output resulting in symptoms of fatigue and breathlessness. The condition is disabling and progressive with a five-year mortality of at least 50%.10 The prevalence increases with age. Latest estimates suggest that in developed countries in those over 70 years of age, the prevalence is over 10%.11 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recognises three phenotypes of HF classified according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) when the ejection fraction is ≤40%; HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) when the ejection fraction is 41–49%; and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) when the ejection fraction is ≥50%.11 All have a similar adverse prognosis but differ in both demographics and co-morbidity and respond differently to treatment.12

AF is also increasing in prevalence due to an ageing population and the rising burden of metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Though rare in the young, it is thought to affect over 5% of those in their 60s and over 20% of those in their 80s.13 It frequently co-exists with HF. Estimates of the prevalence of AF in HFrEF vary from 10% of those with mild symptoms to 50% of those with severe disease.14 The prevalence in HFpEF may be even higher with reported rates of 38% in patients admitted to hospital, and in 52% of those with ‘non-HFrEF.’5,15,16

The two problems adversely interact; in HF, left atrial stretch and fibrosis causing AF occurs because of both the elevated left atrial pressure and maladaptive neurohormonal responses, such as activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Loss of atrial transport in AF further reduces cardiac output and when the ventricular rate is uncontrolled, tachycardia-related myocardial dysfunction can occur. It is frequently unclear whether AF is a cause or consequence of HF but whether it’s the chicken or the egg, the presence of AF confers an adverse prognosis for patients with HF of all phenotypes.17

Modern management of HFrEF

While we now have a strong evidence base for the use of many drugs for HFrEF, the place of digoxin remains vague because of a lack of trial data. Similarly, diuretics improve oedema and breathlessness and are a mainstay treatment but data from trials are largely absent. Digoxin and diuretics were the only treatment for HFrEF until 1987 when the addition of enalapril, an angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor originally developed for the treatment of high blood pressure, was found to improve both symptoms and mortality in patients with severe disease when added to treatment with digoxin (used in 70%) and diuretics.18 This was the first time that any drug had been shown to reduce mortality in patients with HF. Thereafter followed a series of large randomised trials in which the effects of the addition of further neurohormonal blockade with beta blockers then mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) were found to be beneficial, further reducing mortality along with hospitalisation and symptoms. Additional benefit was shown when sacubitril/valsartan (still the only available angiotensin II receptor blocker with a neprilysin inhibitor [ARNI]) was compared to enalapril.19 Drug development for HF then stalled until the advent of SGLT2 inhibitors in the last decade. These drugs, developed originally for diabetes, were noted to reduce cardiovascular mortality in safety trials and were then shown to provide symptomatic and prognostic benefit when used on top of standard drug therapy, although by this time, digoxin was used in only 20% of cases.20,21 Device therapy with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and cardiac resynchronisation devices (CRTs) have also been shown to reduce mortality in sub-groups of patients with HFrEF.

The current ESC HF guidelines produced in 2021 and the focused update in 2023 advise the rapid introduction of the so-called ‘four pillars of therapy’ (ACE inhibitors or ARNI, beta blockers, MRAs and SGLT2 inhibitors) and then dose up-titration along with assessment for device therapies. However, they provide little guidance on the use of digoxin; it ‘may be considered’ for patients in sinus rhythm to reduce the risk of hospitalisation. For patients with co-existent AF, digoxin ‘maybe useful… when other therapeutic options cannot be pursued.’11

The modern management of HFpEF and HFmrEF

Trials of most of the drugs known to be effective for HFrEF have not shown benefit in terms of prognosis or hospitalisations in HFpEF, although there are signals about a prognostic benefit from the MRA spironolactone in the TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist) trial, if data from North and South American patients are analysed in isolation.22 Since the ESC guidelines were published in 2021, the SGLT2 inhibitors dapagliflozin and empagliflozin have both been shown to effectively reduce the combined end point of hospitalisations for HF and cardiovascular death.23,24 Although the effect appears to be primarily on hospitalisation rather than mortality, these drugs should now be considered as standard first-line therapy for patients with HFpEF. The RATE-AF trial included patients with HFpEF and AF and suggested superior symptomatic benefit with digoxin compared to beta blockers (see later).8

Specific data on the efficacy of drugs for patients with co-existent HFrEF and AF

The four pillars of therapy drugs may not all be equally effective in HFrEF with AF. The efficacy of ACE inhibition for patients with co-existent AF remains unknown. For angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) data from post-hoc analyses of randomised control trials are contradictory. In the CHARM (Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) trial, candesartan reduced cardiovascular death and HF hospitalisation in patients with AF with no significant difference in effect size compared to patients in sinus rhythm.25 In ACTIVE (Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events) A and W trials, however, irbesartan did not achieve a significant reduction in the composite outcome of hospitalisation, stroke, myocardial infarction or death from vascular causes in those in AF.26 We still lack proof of efficacy of the ARNI class for the population with HFrEF and AF.19

Given their efficacy in patients with HFrEF and their rate-controlling properties, beta blockers would seem to be an ‘obvious choice’ in cases of HFrEF with AF. A meta-analysis of 11 trials, however, failed to show mortality benefit for patients in AF with no heterogeneity between trials. The lack of benefit in AF was consistent across all sub-groups and there were also no significant reductions in a range of secondary outcomes.27 While beta blockers may still have a role in the management of HFrEF with AF for rate control and symptom improvement, prognostic benefit cannot be assumed and it remains possible that digoxin is equally effective or even superior in this setting.

In EMPHASIS-HF (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure), the effect of eplerenone on major cardiovascular outcomes were similar in those with and without AF.28 Two meta-analyses have investigated the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with HFrEF and co-existent AF. Both found similar efficacy in terms of reduction in HF hospitalisation and cardiovascular death, regardless of baseline rhythm.29,30

To summarise, the management of patients with combined AF and HFrEF is challenging, not only because of the worse prognosis, but because medications with a strong evidence base in HFrEF may have differing efficacy when used in patients with concomitant AF. Ideally, further prospective randomised trials investigating the four ‘pillars of therapy’ in HFrEF with AF should be performed. With its rate-controlling, vago-tonic and inotropic actions, it is possible that digoxin might be highly effective in patients with HFrEF and AF, but this has never been subject to a randomised trial.

Specific data on the efficacy of drugs for patients with HFpEF and AF

Patients with HFpEF are often older and have more co-morbidities than those with HFrEF, and co-existing AF is therefore highly prevalent.31 Trial data are lacking, although it appears that the effects of SGLT2 inhibition in EMPEROR-PRESERVED (Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction) and DELIVER (Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction) trials in those with AF at enrolment were not significantly different to those in sinus rhythm.24,32

The place of digoxin in HFrEF

Small observational studies performed mainly in the 1980s raised alarm about the potential for digoxin toxicity and adverse effects on mortality.6 In 903 patients enrolled in the MILIS (Multicenter Investigation of Limitation of Infarct Size) study of patients post-myocardial infarction, decisions on the use of digoxin were made by the physician but cumulative mortality at a mean of 24 months was found to be 28% for the 281 digoxin-treated patients compared to 11% for the rest who did not receive digoxin.2 Despite the finding that after correction for baseline characteristics of risk, these results were non-significant, concerns remained. The answer to these concerns was arguably provided by the DIG trial published in 1997.7 The trial randomised 6,800 patients with HFrEF (defined as LVEF <45%) in sinus rhythm to receive digoxin or placebo in addition to diuretics and an ACE inhibitor. Frustratingly, AF was an exclusion criterion. The primary outcome of all-cause mortality over a follow-up period of 37 months was unaffected by digoxin but there were significantly fewer all-cause hospitalisations and HF hospitalisations, and a trend toward a decrease in the risk of death attributed to worsening HF. Although more patients on digoxin had suspected digoxin toxicity (11.9% vs. 7.9% on placebo) the rate of hospitalisation for ventricular arrhythmia or cardiac arrest was not significantly different. Deaths thought to be due to arrhythmia were slightly increased, though classification problems make this uncertain. Subsequent post-hoc analyses suggested that digoxin at low serum concentrations significantly reduced mortality and hospitalisations while higher levels were associated with marginal excess mortality.33

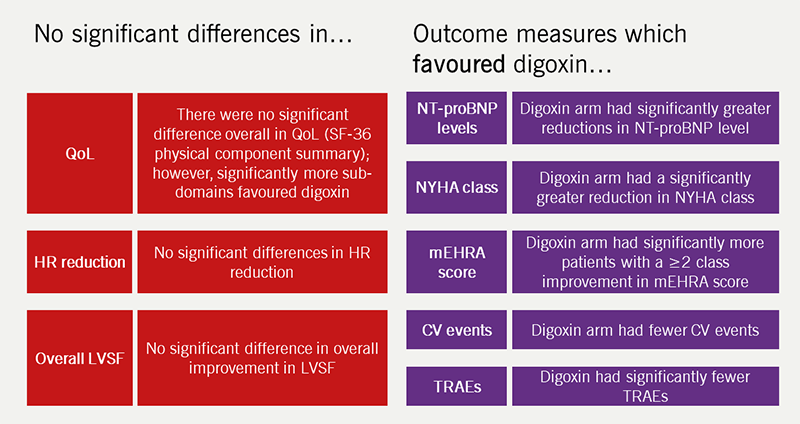

The lack of randomised trials of digoxin in patients with HFrEF and AF means we have no reliable information on risks and benefits. The likely lack of prognostic benefit of beta blockers in this group makes further trials comparing digoxin with other rate-controlling drugs desirable. The RATE-AF trial was the first randomised study to assess the effect of digoxin in patients with both AF and HF of all three phenotypes.8 The trial recruited 160 patients aged 60 years or older with permanent AF and dyspnoea, classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or higher, and randomised them to low-dose digoxin or the beta blocker bisoprolol. The proportion of patients within the trial with HFrEF was small – only 19% had a baseline LVEF <50%. The long-term outcome data are yet to be published but at 6 months, although the primary end point of quality of life for patients in the digoxin arm was not different from those on bisoprolol, they had greater improvements in symptoms, significantly fewer treatment-related adverse events and a greater reduction in NT-proBNP compared to those in the beta blocker arm (figure 3). Both treatment arms were equally effective in reducing heart rate without compromising left ventricular heart function.8

| Adapted from Kotecha et al. Effect of Digoxin vs Bisoprolol for Heart Rate Control in Atrial Fibrillation on Patient-Reported Quality of Life: The RATE-AF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020;324(24):2497–2508. Key: CV = cardiovascular; HR = heart rate; LVSF = left ventricular systolic function; mEHRA = modified European Heart Rhythm Association functional class; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA = New York Heart Association; QoL = quality of life; RATE-AF = Rate Control Therapy Evaluation in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation; SF-36 = Short-Form 36 Physical Component Summary score; TRAEs = treatment-related adverse events |

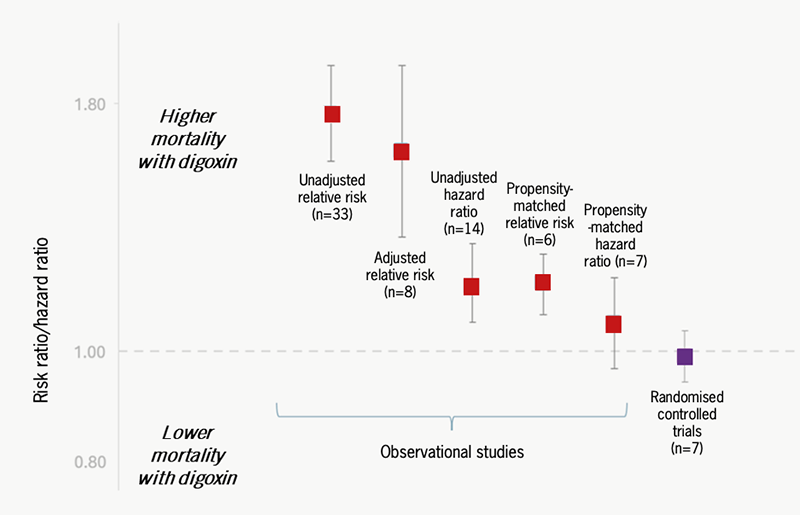

Retrospective analysis of large data sets has also been helpful in establishing the effects of digoxin. In clinical practice, digoxin is often given to older and sicker patients with HF with more characteristics predictive of mortality – so called ‘prescription bias’. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and randomised trial data on the safety and efficacy of digoxin, the pooled risk ratio for death with digoxin was 1.76 (adverse) in unadjusted analyses of observational studies, 1.18 for propensity-matched studies and 0.99 (i.e. neutral) for randomised trials, indicating that baseline differences between treatment groups were indeed responsible for apparent adverse mortality effects (figure 4).6 Across all study groups, digoxin was associated with a significant reduction in hospitalisation. An updated meta-analysis has confirmed a neutral effect on total mortality for both digoxin versus placebo and digoxin versus active comparators, and significant reductions in hospitalisation for HF and HF deaths when restricted to pooled randomised trials.34

| Adapted from Ziff et al.6 Safety and efficacy of digoxin: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and controlled trial data. BMJ 2015;351:h4451. |

Digoxin in HFpEF with AF

There are no published trials that have restricted recruitment to patients with HFpEF and AF. Commonly used medications for rate control include beta blockers, digoxin and calcium-channel blockers. In the RATE-AF trial, 81% had LVEF >50% and so fulfilled many criteria for HFpEF, suggesting that digoxin is both effective and tolerable in this setting with better short-term effects on patient symptoms.8 The authors also showed that there were significant improvements in parameters of systolic function with digoxin compared to treatment with beta blockers.35

Is there still a place for digoxin?

Much of the concern about the potential for digoxin toxicity and excess mortality due to arrhythmia has been allayed by the meta-analysis of Kotecha and team. They have provided strong evidence that signals of excess mortality associated with digoxin use for HF and/or AF from non-randomised studies were the result of ‘confounding by prescription.’ In brief, digoxin has been used for sicker patients with inevitably poorer outcomes and associations with excess mortality are almost certainly non-causative. Their analysis of randomised studies of digoxin has revealed that its use is associated with small but significant reductions in hospitalisations and HF deaths without excess mortality. It is possible that the pro-arrhythmic effects of this inotropic drug are balanced by its anti-arrhythmic, vago-stimulatory effects. It must be admitted, however, that we have inadequate information about the beneficial or adverse effects of digoxin use in patients with HFrEF on modern-era maximal medical therapy and high levels of device therapy. We also have very little information on the use of digoxin for patients with HF and co-existent AF. Two trials are underway, so there may be scope for a further review paper on this topic after their publication.36,37 Digoxin has a risk of toxicity but by keeping the dose down to 0.25 mg once daily or lower, and monitoring renal function regularly so that serum concentrations are low, these risks are very small.8,33

So, based on current evidence, which patients should be considered for digoxin therapy? We acknowledge that in 2024, patients with both HF and AF can be adequately managed without digoxin. There are, however, some clinical settings in which digoxin appears to confer an advantage to patients. These are:

Elderly patients in AF with stable, mild symptoms of HF of any phenotype. Such patients are likely to have better wellbeing on digoxin than beta blockers.

Patients with HFrEF and NYHA class II–IV HF without AF who have a high risk of hospitalisation, despite receiving maximal-tolerated doses of the four ‘pillars of therapy,’ titrated diuretic therapy and CRT, if indicated. Digoxin is likely to reduce the need for hospitalisation and may confer a marginal advantage in reducing HF death.

It is also reasonable to use digoxin in addition to, or in place of, beta blockers for rate control in patients with AF and HFrEF given the lack of mortality benefit from beta blockade in such patients.

William Withering would probably be surprised to know that after almost 250 years, the precise place of digoxin in the treatment of HF has still not been defined. We suspect, however, that he would be pleased to know that Kotecha and team in Birmingham are, in effect, continuing his work on digoxin within a mile of his former residence and that his foxglove-derived treatment for dropsy is still improving lives.

Key messages

- Digoxin does not increase mortality in heart failure (HF). Meta-analysis of digoxin trials indicates that reports of increased mortality are explained by prescription bias. Randomised trial data show a neutral effect

- Digoxin improves symptoms in HF. Data from randomised trials show that it reduces the need for hospitalisation in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in sinus rhythm, and in patients with AF, it is superior to beta blockers in improving symptoms with lower rates of treatment-related adverse events

- Digoxin should also be considered for rate control in patients with HFrEF and AF, given the lack of mortality benefit from beta blockers.

Articles in this supplement

Digoxin: a look back and a look forward

Digitalis – from Withering to the 21st century

Digoxin: monitoring, limitations of its use, and managing toxicity

Conflicts of interest

KVB – PhD (awarded in 2020) was funded through the RATE-AF trial’s Career Development grant awarded to Professor Dipak Kotecha: National Institute for Health Research UK – CDF-2015-08-074 and HTA-130280.

All authors have received an honorarium for their work on this supplement.

Funding

KVB – Currently funded by a British Heart Foundation Career Development Research Fellowship (for Nurses & Healthcare Professionals) FS/CDRF/21/21032.

Contributions

All authors (SET, KVB, JNT) contributed to the concept, design, drafting and final writing of the manuscript.

Sophie E Thompson1

Internal Medicine Trainee

([email protected])

Karina V Bunting1,2

British Heart Foundation Research Fellow

Jonathan N Townend1,2

Consultant Cardiologist and Honorary Professor of Cardiology

1 Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Trust, Birmingham

2 Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham

References

1. Withering W. An Account of the Foxglove, and Some of its Medical Uses: With Practical Remarks on Dropsy and Other Diseases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

2. Muller JE, Turi ZG, Stone PH et al. Digoxin therapy and mortality after myocardial infarction. Experience in the MILIS study. N Engl J Med 1986;314:265–71. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198601303140501

3. Lee AY, Kutyifa V, Ruwald MH et al. Digoxin therapy and associated clinical outcomes in the MADIT-CRT trial. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:2010–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.016 [Epub online ahead of print]

4. Goldberger ZD, Alexander GC. Digitalis use in contemporary clinical practice: refitting the foxglove. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:151–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10432

5. National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. National Heart Failure Audit (NHFA) 2024 Summary Report (2022/2023 NHFA data) [Online]. Available at: https://www.nicor.org.uk/heart-failure-heart-failure-audit/ (accessed 21 May 2024)

6. Ziff OJ, Lane DA, Samra M et al. Safety and efficacy of digoxin: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and controlled trial data. BMJ 2015;351:h4451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4451

7. Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:525–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199702203360801

8. Kotecha D, Bunting KV, Gill SK et al. Effect of digoxin vs bisoprolol for heart rate control in atrial fibrillation on patient-reported quality of life: the RATE-AF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:2497–508. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.23138

9. Turakhia MP. Digoxin in atrial fibrillation? Leave it out of the medicine cabinet. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1075–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.015

10. Jones NR, Roalfe AK, Adoki I et al. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1306–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1594 [Epub online ahead of print]

11. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

12. Liang M, Bian B, Yang Q. Characteristics and long-term prognosis of patients with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol 2022;45:5–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23754 [Epub online ahead of print]

13. Khurshid S, Ashburner JM, Ellinor PT et al. Prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation among older primary care patients. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2255838. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55838

14. Anter E, Jessup M, Callans DJ. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: treatment considerations for a dual epidemic. Circulation 2009;119:2516–25. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821306

15. Batul SA, Gopinathannair R. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: a therapeutic challenge of our times. Korean Circ J 2017;47:644–62. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2017.0040 [Epub online ahead of print]

16. Chiang C-E, Naditch-Brûlé L, Murin J et al. Distribution and risk profile of paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation in routine clinical practice: insight from the real-life global survey evaluating patients with atrial fibrillation international registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5:632–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.112.970749 [Epub online ahead of print]

17. Mamas MA, Caldwell JC, Chacko S, Garratt CJ, Fath-Ordoubadi F, Neyses L. A meta-analysis of the prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:676–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfp085

18. CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1987;316:1429–35. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198706043162301

19. McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1409077 [Epub online ahead of print]

20. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1413–24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2022190 [Epub online ahead of print]

21. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995–2008. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1911303

22. Pfeffer M, Claggett B, Assmann S et al. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation 2015;131:34–42. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013255 [Epub online ahead of print]

23. Solomon SD, de Boer RA, DeMets D et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with preserved and mildly reduced ejection fraction: rationale and design of the DELIVER trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2021;23:1217–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.2249 [Epub online ahead of print]

24. Packer M, Butler J, Zannad F et al. Effect of empagliflozin on worsening heart failure events in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: EMPEROR-Preserved trial. Circulation 2021;144:1284–94. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056824 [Epub online ahead of print]

25. Olsson LG, Swedberg K, Ducharme A et al. Atrial fibrillation and risk of clinical events in chronic heart failure with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results from the candesartan in heart failure-assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1997–2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.060 [Epub online ahead of print]

26. Yusuf S, Healey JS, Pogue J et al.; ACTIVE I Investigators. Irbesartan in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:928–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1008816

27. Kotecha D, Holmes J, Krum H et al. Efficacy of β blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet 2014;384:2235–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61373-8 [Epub online ahead of print]

28. Swedberg K, Zannad F, McMurray JJV et al. Eplerenone and atrial fibrillation in mild systolic heart failure: results from the EMPHASIS-HF (eplerenone in mild patients hospitalization and survival study in heart failure) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1598–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.063

29. Zheng S, Lai Y, Jiang C et al. Effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2024;47:58–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.14880 [Epub online ahead of print]

30. Pandey AK, Okaj I, Kaur H et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors and atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e022222. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.022222 [Epub online ahead of print]

31. Deichl A, Wachter R, Edelmann F. Comorbidities in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Herz 2022;47:301–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-022-05123-9 [Epub online ahead of print]

32. Butt JH, Kondo T, Jhund PS et al. Atrial fibrillation and dapagliflozin efficacy in patients with preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:1705–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.718 [Epub online ahead of print]

33. Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM. Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure. JAMA 2003;289:871–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.7.871

34. Champsi A, Mitchell C, Tica O et al. Digoxin in patients with heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 5.9 million patient years of follow-up. Lancet [Preprint] 2023. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4544769 (accessed 21 May 2024)

35. Bunting KV, Mehta S, Gill SK, Steeds RP, Kotecha D. Digoxin improves systolic cardiac function in patients with AF and HFpEF: the RATE-AF randomised trial. Eur Heart J 2022;43(suppl 2). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac544.793

36. Bavendiek U, Berliner D, Aguirre Dávila L et al. Rationale and design of the DIGIT-HF trial (digitoxin to improve outcomes in patients with advanced chronic heart failure): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:676–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1452

37. van der Meer P, Rienstra M, van Veldhuisen DJ. Digoxin evaluation in chronic heart failure: investigational study in outpatients in the Netherlands (DECISION). University Medical Center Groningen Cardiology Research Institute [online] 2024. Available at: https://www.groningencardiology.com/research/decision/ (accessed 22 May 2024)