There is little doubt that demand on the National Health Service (NHS) has exceeded supply. Given the rhetoric of no more money, no new workforce, and no new estates, it is incumbent on us all to make better and more efficient use of the limited resource we do have, improve how we work together as one integrated health, community and social care ecosystem, and increase the value of every action we take. Cardiovascular services are no exception.

The challenging questions we must ask ourselves are:

- How and why did we reach this status quo?

- What are the consequences of continuing to operate in the current care model?

- What should we do about it, by when and how?

- Are we really offering true value across the whole patient journey (and if we think we are, how do we know)?

- Do we honestly look outside our own business or service delivery units?

Unified value and operational integration

Let’s consider value for a moment. Can the NHS deliver true value-based care unless integrated-care systems (ICSs) are operationally integrated; but how can ICSs integrate if individual providers (for example social care, community services and out-of-hours care) continue to have siloed contracts, budgets, accountabilities, and priorities?

Furthermore, do having artificial service line budgets generate the best outcomes? For example, a restrictive medication management budget at the expense of enabling guideline-based therapies that ultimately reduce preventable unplanned admissions. Value across the whole patient pathway and across the whole system is required (what I’ll refer to as ‘unified value’), not just the perceived value of our own individual actions or within our delivery units.

The urgency for all professionals caring for an individual to be enabled by integrated-care boards (ICBs) to deliver unified value – to act coherently and collectively, is unquestionable, given the current demand trajectory is unsustainable for patients, staff, and the system alike. But what does ‘act’ mean? I suspect we can all agree a tangible paradigm shift is needed, the outcome needs to be radical, sustainable and wholesale, on a scale never seen in modern times. Not another NHS management restructure, but a fundamental change in system-operating model, culture, values, expectations, vision, and proactive patient activation.

Dynamic patient-centred care models

To truly consider the above, we need to explore the root cause of the current situation. Arguably, we have a highly pressured, clinically reactive and financially driven healthcare system that is not integrated with social care or the wider community. It is made up of healthcare professionals (HCPs), clinical specialities, managers, support staff and providers, often working in silos, so busy firefighting that colleagues don’t have the bandwidth to individually or collectively take a step back and review their patients’ journeys across the wider system.

Perhaps a reactive system is an unsurprising consequence of chronic under-investment and demand culture. Finance and demand stresses are opposing forces that lead to unrealistic expectations, increasing wait times, a stressed workforce, and a potential reduction in value.

The consequence of a demand-driven reactive system naturally raises the question – what creates demand? Does the work we do, or what we are compelled to do, always translate to better outcomes?1 How can we assure ourselves that we are not feeding demand due to a failure of delivering unified value?

Demand is made worse by the accountability paradox, that is, a resource-light, demand-heavy system where pressured HCPs sometimes feel personally accountable when things go wrong (or behave defensively to avoid mishaps) due to system factors. More low-value clinical activity may be generated by professionals to mitigate risk, such as test, treat or refer. Personalised care discussions with patients or their carers can help to relieve this burden.

Let’s consider a patient with frailty who has hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and arthritis of the knee. They are referred to the community musculoskeletal service, who in turn refer to orthopaedics. She is listed for surgery, which is delayed given diabetes is discovered at the pre-op clinic. Hospital length of stay is prolonged due to the underlying CKD and complications from previously underdiagnosed heart failure. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is optimised with a rapid up-titration four-pillar approach. The patient subsequently falls on the ward due to postural hypotension, causing a hip fracture. They are eventually discharged to a frailty virtual ward where her medications are reduced, and an advance care plan is put in place. Data have shown that a significant number of patients are admitted acutely due to complications of cardiac drugs.

How could our patient have had a better outcome with lower healthcare resource utilisation? How can we deliver this utopia at scale? Maybe the answer lies in a truly integrated healthcare, community and social ecosystem, with proactive left-shift and consideration of multi-morbidity and frailty, teams working together in near real-time around the patient, rather than in series, so-called ‘dynamic patient-centric care’. In this scenario, teams should be culturally, educationally and contractually enabled to deliver unified value, which includes personalised care by definition.

The consequence of silo working

If the NHS continues down the route of teams working in silos and in series, with people shoe-horned into pathways and protocols, so-called ‘protocol hypnosis’, what will the future hold? This approach is diametrically opposed to unified value and dynamic patient-centric care models. We all know that patients don’t fit neatly into pathways, so why do we continue to develop more of them? Has our system been set up to fail? How can we systematically release capacity to focus on left-shift, namely prevention, early diagnosis of long-term conditions (LTCs) and frailty, LTC optimisation and admission avoidance, when we are spending so much time and resource on reactive care?

Dichotomous rigid structures such as primary or secondary care, and out-of-hours or in-hours care, we should argue are not only antiquated but create needless barriers to good care. If it is too difficult to restructure, the solution perhaps lies in the way in which different parts of the system work together, collaboration with industry, citizens and employers as partners, fully capitalising on current assets, such as physician associates and pharmacists, and better use of technology. For that to happen, to achieve true dynamic patient-centric care, professionals from all parts of the system need to have a common shared purpose, both at patient level and more fundamentally at system and cultural level. If that purpose lies in value-based medicine and personalised care, the financial and system benefits will follow.

Next steps

What does this all mean? First and foremost, it requires the willingness to change, strong cross-organisational leadership and culture change, ensuring patients and grass-roots clinicians feel empowered to consider sustainable principles of a new healthcare ecosystem:

- Proactive left-shift (supported by resource and contracts) focusing on prevention, and early diagnosis/optimisation of LTCs, and early diagnosis of frailty/end-of-life with individualised care planning.

- Empowering citizens, community HCPs, e.g. pharmacists and employers (including the public sector), in cardiovascular risk factor detection and monitoring, e.g. hypertension.

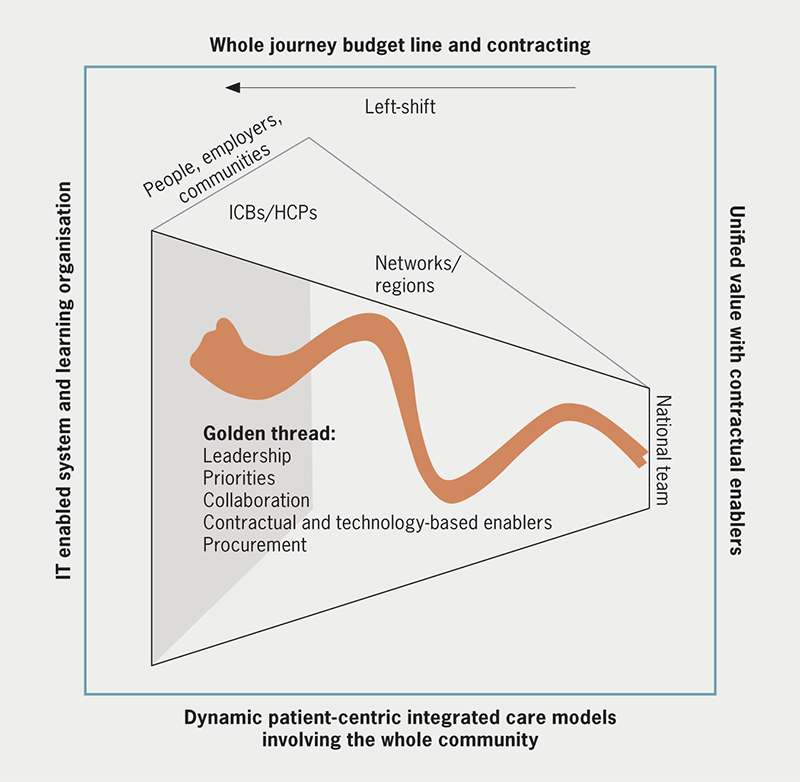

- Dynamic patient-centric care models, seamless care from community to tertiary care, out-of-hours and in-hours, working in an integrated way in near real-time, rather than teams working in series. These concepts should run as a golden thread throughout all levels of the NHS (figure 1).

- Health systems focused on unified value-based care, rather than perceived value within siloed departments.

- HCPs enabled through resource, data, technology, contracts and education.

- Systems of care should be both process- and outcome-focused learning organisations. Outcomes should include measurements of harm and unintended consequences, e.g. falls from cardiac drugs.

- No patient should be disadvantaged, and the inequality gap should be narrowed and not widened.

- Radical commissioning arrangements that enable quality-driven dynamic patient-centric care models across the system, rewarded by value, where resource follows the patient.

- The evidence should not be blindly applied without consideration of how applicable the study cohort is to the real world.

- National funding to support transformation at scale.

- Easier collaboration with the private sector.

- National and rapid procurement of technology.

| Key: HCP = healthcare professional; ICB = integrated-care board; IT = information technology |

Conclusion

Whatever the solution, it is clear those who work in the cardiovascular space need to be enabled to deliver a new value-based way of working, in near real-time with other disciplines. The only question now is, are we bold enough to lead the way?

Conflicts of interest

I have received speaker or consulting honoraria from Abbott, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Edwards, Healthy.io, Medtronic, Novartis, and Omron. In addition I have a fixed term contract with AstraZeneca as head of external medical engagement and innovation.

Funding

None.

Reference

1. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q 2005;83:691–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x