The combination of atrioventricular (AV) block – specifically high-grade AV block– within the setting of myocarditis, is a rarely encountered clinical phenomenon. It is commonly encountered in infiltrative cardiomyopathies but may be associated with myocarditis.

Beyond conventional investigation and consideration of endomyocardial biopsy, there is a paucity of data to guide clinicians with regards to the issue of heart rhythm disorder. Options include a ‘watch-and-wait’ policy, anti-arrhythmic drugs, consideration of a permanent pacemaker or, alternatively, a wearable or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

The case encapsulates the difficulties facing clinicians with such pathology and the need to further investigate and risk stratify such patients.

Introduction

Atrioventricular (AV) block is an uncommon complication of myocarditis, which is most often observed in combination with underlying conditions such as that caused by cardiac sarcoidosis (CS), giant cell myocarditis (GCM) and acute lymphocytic myocarditis. Myocarditis is a broad term that describes inflammation of the myocardium, which can range from mild and self-limiting to fulminant variants that require cardiac transplantation. Patients with proven GCM and CS may benefit from immunosuppression, and it is important to investigate for underlying infiltrative disease in cases of myocarditis and AV block as specific treatments may alter disease progression and outcomes.1 Sustained AV block within myocarditis of an unknown aetiology has been rarely observed within adults and requires an individualised case-by-case approach.

A prior retrospective observational study of 31,760 patients with myocarditis documented that 363 (1.1%) had high-degree AV block, and of these patients 42.6% required temporary pacing, 19.7% required permanent pacemaker (PPM) insertion and the mortality rate was significantly raised at 15.5% compared to 2.7% without AV block.2 Female gender and Asian ethnicity were both independently associated with an increased likelihood of developing AV block in myocarditis. It is likely that whilst this is an uncommon complication of an uncommon condition, appropriate management of the AV block may significantly reduce morbidity and mortality.

Case presentation

A previously fit 55-year-old woman presented to her local emergency department (ED) with acute-on-chronic dyspnoea. The patient described several periods of exertional chest pain and exertional dyspnoea over the preceding nine months. The lady was a keen equestrian. There was no significant past medical history, and the lady was only prescribed hormone replacement therapy.

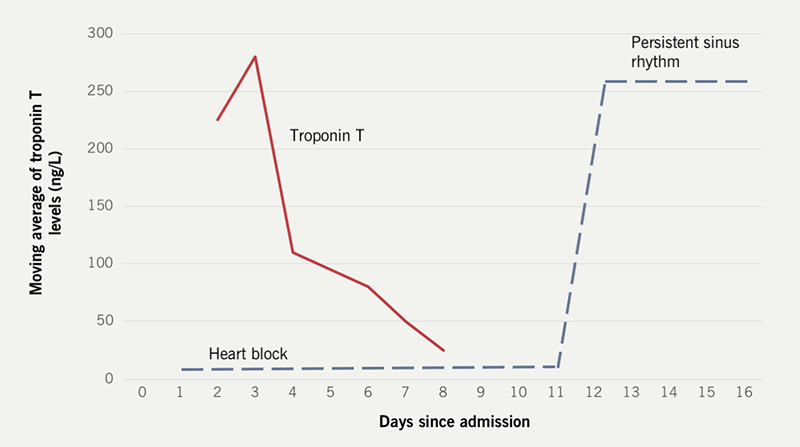

She had evidence of pulmonary congestion, raised serum troponin I (889.7 ng/L) and the twelve-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) documented complete AV block. Hence the individual was transferred for tertiary cardiology management of the presentation. Invasive coronary angiography found no evidence of obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease. The index transthoracic echocardiogram documented a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) with multiple areas of regional wall motion abnormality. She did not develop any haemodynamic compromise from the AV block. An inpatient cardiac MR study revealed diffuse myocardial oedema without late gadolinium enhancement. The lady was introduced to conventional heart failure therapies including an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and a sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor. Inpatient positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) and high-resolution chest CT were performed to exclude evidence of active CS. Both investigations were normal. The troponin T value on admission was 111 ng/ml, which progressively dropped. Unfortunately, serum ACE was not measured.

An endomyocardial biopsy was contemplated, but due to the effects of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) on the National Health Service infrastructure, it was not undertaken.

Anti-nuclear antibody screening was negative, and the lady had recurrently negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) swabs for severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-related coronavirus-2 (SARS- COV-2) and influenza A and B whilst an inpatient.

Following extensive and recurrent discussion within the local heart failure and devices multidisciplinary team meetings, and after involving regional and national colleagues, a dual-chamber pacemaker was ultimately implanted.

Upon discharge, the patient remains well at six months, with a repeat cardiac MR demonstrating a full recovery in LVEF and no evidence of arrhythmias on pacing check. She was not prescribed immunosuppression or beta blockade at any point. She has remained asymptomatic; however, monitoring has revealed that since pacemaker insertion, she has had a repeat episode of reduced ejection fraction alongside an increased pacing burden due to recurrence of high-grade AV block.

Discussion

The combination of AV block and myocarditis remains rare. Due to the scarcity, presentation with dual pathology should mandate a search and exclusion of myocardial infiltrative disorders. Within this case, the extensive screen was negative. An endomyocardial biopsy was considered but due to the COVID-19 pandemic and effects on local and regional hospital infrastructure, it was not performed.

The most widely recognised disease entity with combined presentations of AV block and myocarditis is that of CS. Previous consensus suggests a presentation with CS and AV block should mandate consideration of ICD implantation due to the possibility of myocardial infiltration via non-caseating granulomata and subsequent risk of sudden cardiac death mediated by ventricular arrhythmias.3 In this case, there was no clear sarcoidosis and screening for it was negative.

In such individuals where infiltrative disease has been excluded, there are three therapeutic options allied to the heart rhythm. Firstly, there is an active surveillance option of ‘watch and wait’; clearly this causes angst and concern for both clinicians, patients and families due to the theoretical risk of sudden cardiac death mediated by bradycardia or tachyarrhythmias.

PPMs and ICDs are other more permanent therapeutic options but need to be considered carefully. Both respective implantation procedures carry risk, balanced against a lifetime of commitment to device aftercare and, likely, to exposing a young patient to recurrent generator changes and revision with the consequent longer-term risks of lead deterioration and systemic infection.

In this specific case, there were recurrent discussions amongst heart failure physicians, electrophysiologists, the patient, family members, transplant centres and the national sarcoidosis centre. This was made challenging due to the immediacy of a wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The combination of high troponins, oedema on cardiac MR imaging, and the intermittent nature of prior symptoms suggested a relapsing and remitting inflammatory process that behaved comparable to CS, with a few key differences. Ultimately a dual-chamber pacemaker was considered the most appropriate option as serial telemetry did not demonstrate ventricular arrhythmias; there was no myocardial scarring or other malignant features, in terms of investigations, nor a significant family history. The patient participated throughout with the shared decision making. Genetic testing was discussed with the genetics MDT and was felt to be unnecessary. The diagnosis in this case was recurrent myocarditis with complete AV block of unclear aetiology. After several years of follow up, the patient’s condition continues to wax and wane, and she remains asymptomatic without the requirement for immunosuppression. Furthermore, she has had no episodes of ventricular arrhythmias that would suggest prompt consideration of an ICD.

It is noteworthy that beyond presentations of myocarditis and AV block, there is conspicuous absence of longer-term data beyond the index hospital admission, and it is of urgent importance that there is longer-term follow up of such individuals and further study via registry and institutional studies.

Conclusion

If the presentation of myocarditis and AV block is due to CS then the patient may receive an ICD due to the heightened risk of ventricular arrythmias and sudden cardiac death, the risk of which is greater at lower ejection fraction.4

Key messages

- The combination of atrioventricular (AV) block and myocarditis should lead to the exclusion of infiltrative myocardial disease

- The optimal management of such patients without cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) remains unknown and urgently require further long-term characterisation and investigation

- If the presentation of myocarditis and AV block is due to CS, then the patient should receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation due to the heightened risk of ventricular arrythmias and sudden cardiac death.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Statement of consent

Patient consent has been obtained in written form.

References

1. Cooper L, Blauwet L. When should high-grade heart block trigger a search for a treatable cardiomyopathy? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4:260–1. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.111.963249

2. Ogunbayo GO, Elayi SC, Olorunfemi O, Elbadawi A, Saheed D, Sorrell VL. Outcomes of heart block in myocarditis: a review of 31,760 patients. Heart Lung Circ 2019;28:272–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2017.12.005 [Epub online ahead of print]

3. Gilotra N, Okada D, Sharma A, Chrispin J. Management of cardiac sarcoidosis in 2020. Arrhythm Electrophysio Rev 2020;9:182–8. https://doi.org/10.15420/aer.2020.09

4. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 2018;138:e210–e271. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000548