Cardiotoxicity, including left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, is a dreaded side-effect of selected drugs that are widely used in oncology. Guidelines recommend the assessment of LV systolic function, primarily by echocardiography, before and during exposure to cardiotoxic medications. However, apart from LV ejection fraction (LVEF), echocardiography reports include dozens of numerical data points and other detailed information familiar to cardiologists, but which may not be familiar to other specialties.

With a rising need for echo in oncology patients, and with no cardio-oncology service within our hospital, we assessed what is understood by oncologists regarding the information provided within an echocardiographic report, and what action they take subsequent to the report. Morriston Cardiac Centre provides tertiary care to a population of 1.2 million and conducts 12,000 transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) annually.

We ran a survey of all consultant clinical oncologists in Wales, using a set of multiple-choice questions via Google Forms. We presented the responders to our questionnaire with a set of hypothetical echocardiographic findings, drawn from common clinical scenarios, and asked what they would do if they received a report containing such a finding. Our questionnaire was completed by 14 of 19 (74%) oncology consultants.

Only a little better than half reported low-to-moderate confidence in interpreting the findings that echo reported. Oncologists varied in their level of confidence and understanding of what TTE findings meant, and the responses to commonly reported echocardiographic findings (e.g. actions they would take if echo report stated low-normal ejection fraction) had inhomogeneity.

Our work supports the utility of a dedicated cardio-oncology clinical pathway or service, which would assist with these queries, and may even obviate them, by providing the echo report directly to a cardio-oncologist.

Introduction

Cardiotoxicity, primarily in the form of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, is a feared side-effect of selected drugs that are widely used in oncology.1,2 To reduce its occurrence, practice guidelines consistently recommend assessing LV systolic function, primarily by echocardiography, before and during exposure to cardiotoxic medications.3

However, apart from left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), contemporary echocardiography reports include dozens of numerical data points, as well as detailed information about haemodynamics, all the cardiac chambers and the heart valves; and some of this information may be clinically relevant. A lot of the information is presented using abbreviations, which are familiar to cardiologists, but may not be familiar to other specialties.

Due to a recent increase in the demand for echocardiographic assessment in oncology patients, and in the absence of a dedicated cardio-oncology service in our hospital, we were stimulated to assess what oncologists understand from the information contained in our echocardiographic reports, and what actions they take after receiving the report. This is a first step in an ongoing effort to reconfigure and tailor our reports to the needs of our users.

Setting

Morriston Cardiac Centre performs 12,000 transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) a year and offers tertiary cardiac services to a population of approximately one million, in West Wales, UK. TTE reports are structured according to the minimal dataset recommended by the British Society of Echocardiography (BSE).4 TTE studies are performed and reported by BSE-accredited sonographers, and are emailed to the requesters in pdf format.

Table 1. List of hypothetical echocardiographic findings, with actions available to recipients of the report (they were asked to choose one option only)

| Statement in the report |

|---|

| Low-normal LVEF |

| Dilated left atrium |

| Type I diastolic dysfunction |

| Moderately dilated ascending aorta, 4.8 cm |

| Limited views, unable to measure LVEF, but visual impression of preserved systolic function |

| LV concentric remodelling |

| Mild MR, AR, TR |

| Moderate TR |

| Circumferential pericardial effusion, 1 cm |

| Severe LV impairment |

| Severe MR |

| Mild PR (pulmonary regurgitation) |

| Mild AV thickening, aortic valve area 3 cm2 |

| Sigmoid septum noted |

| Available actions |

| No action |

| Start beta blockers and ACEi |

| Request alternative test |

| Informal discussion with cardiology colleague |

| Formal referral to cardiology |

| Phone echo department and ask for clarification |

| Key: ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AR = atrial regurgitation; AV = aortic valve; LV = left ventricular; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MR = mitral regurgitation; TR = tricuspid regurgitation |

Method

We ran an online survey of all consultant oncologists in Wales from July 2024 to September 2024, using a set of multiple-choice questions (table 1) administered via Google Forms. We presented the responders to our questionnaire with a set of hypothetical echocardiographic findings, drawn from common clinical scenarios, and asked what exactly they would do if they received a report containing such a finding. We focused on the potential impact of the oncologists’ choices on the workload of the echo department. We also documented the degree of confidence that the oncologists have in interpreting common TTE findings by including a scale (1 being the lowest confidence and 4 being very confident) in the survey, their familiarity with common echo terms by including a scale on how comfortable they are in interpreting echo terms, as well as the length of time since responders were appointed to a consultant post.

Results

Confidence and comprehension

Fourteen out of 19 (73.7%) oncology consultants in Wales responded to our survey. Three-quarters of them had been in post for more than 10 years. Slightly more than half (53.3%) reported low-to-moderate confidence in interpreting the findings reported by echo, and hardly anyone (6.7%) was familiar with abbreviations that appear recurrently in TTE reports, such as TAPSE (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion), GLS (global longitudinal strain), MVA (mitral valve area), PLAX (parasternal long axis), and RVH (right ventricular hypertrophy).

Action taken on receipt of the report

Overall, respondents were reluctant to seek clarification of findings in an echo report, when they were not sure about their significance. When clarification was needed, in most cases it took the form of a referral to the cardiology service.

Specific clinical scenarios

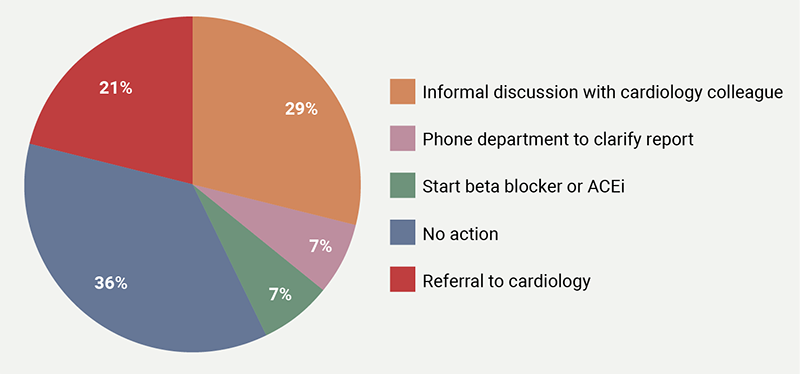

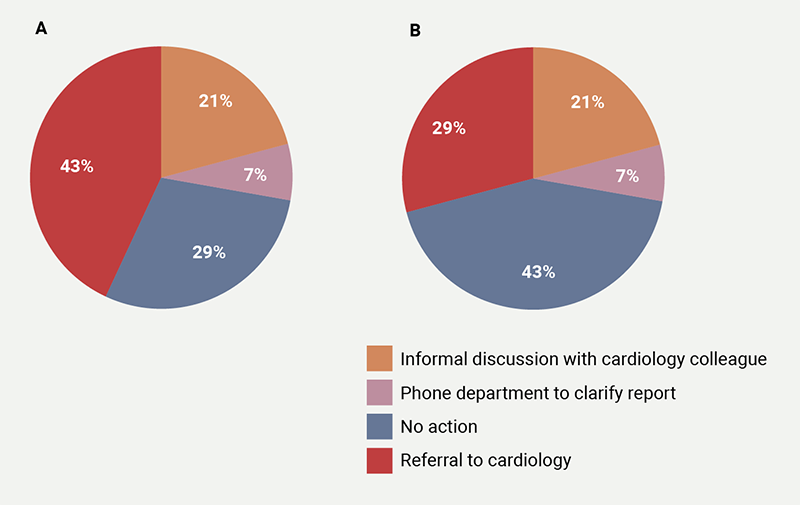

The oncologists’ responses were most inhomogeneous to a finding of ‘low-normal LVEF’ (figure 1), where they reported five different courses of action: 36% reported no action, 29% opted for informal discussion with cardiologist, 21% chose referral to cardiology and 7% choose phoning the echo department for further clarification, and 7% chose to start beta blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi). Marginally less variable (four courses of action reported), were the responses to a finding of a ‘dilated left atrium’ (figure 2A) (43% would refer to cardiology, while 29% and 21% would either take no action or ask for an informal cardiology opinion, respectively, and 7% would phone the echo department for further clarification) or to a finding of ‘concentric LV remodelling’ (figure 2B) (43% no action, 21% cardiology referral, 29% informal cardiology discussion and 7% who would phone the echo department). In the case of ‘diastolic dysfunction’, 57% would take no action, 36% would refer to cardiology, with the remainder opting for informal discussions. A finding of ‘aortic valve sclerosis’ with normal aortic valve area prompted cardiology referral in 43% of the cases, no action in 36% and 21% chose informal discussion. A ‘circumferential pericardial effusion of 1 cm’ prompted cardiology referral in 67% of cases, while an ‘inconclusive scan for the assessment of LVEF’ prompted a request for an alternative test in 47% of cases, with ‘no action’ chosen in a similar proportion (47%), and the remainder 6% opting for informal discussions.

| Key: ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

A finding of ‘mild AR, MR, TR’ prompted cardiology referral in 53% of cases with the remainder opting for no action.

In scenarios with ‘severe LV dysfunction’, ‘moderate ascending aortic dilatation’ and ‘severe mitral regurgitation’ the majority opted for referral to cardiology where 87%, 80% and 100% chose referral to cardiology, respectively.

Discussion

Findings

In a small sample, which nevertheless includes 73.7% of the oncologists in Wales, consultants demonstrated varying degrees of confidence and comprehension of TTE findings, and inhomogeneity in the responses to commonly reported echocardiographic findings.

Although there is a vast literature on the appropriateness and clinical impact of TTE, there is hardly any guidance about the use of echocardiography by non-cardiologists,5 and it is based on expert opinion rather than on data. From this perspective, our study is truly novel.

We found that more than half of the oncologists were not confident with their interpretation of the echo report, and that one in eight would phone the echo department for clarification of findings such as dilated left atrium (LA), circumferential pericardial effusion or LV concentric remodelling. This is clearly an area of potential improvement, because phoning the echo department to ask what to do – clinically – with the information that the LA is dilated, or that there is LV concentric remodelling, yields no benefit, as no cardiologist or sonographer could answer this question without clinical context. This shows the need for clinical guidance for non-cardiologists who are receiving echocardiography reports. In a patient with cancer, LA enlargement may be a marker of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), for example, but is this in any way relevant for such a patient, whose survival is determined primarily by the malignancy?

Placing the significance of an echo finding in the clinical context, and making treatment or investigation decisions based on that is complex, and cannot be devolved onto sonographers or cardiologists approached informally.

Avenues for the future

Our findings suggest the usefulness of a dedicated cardio-oncology clinical pathway or service, which would absorb the significant proportion of cases generating queries, and would probably even eliminate them, by providing the echo report directly to the cardiologist. This approach is increasingly accepted and promoted,6,7 but requires resources, which may not be universally or readily available. It is difficult to translate the lack of such a service into a measurable impact on any of the quantitative indices to which commissioners and funding bodies respond, which means it is unlikely to represent a priority for hospital management. One of the solutions can be to have advanced level clinical scientists, akin to valve clinic physiologists, to provide comment on what requires escalation to a cardiologist. Other potential low-cost solutions would be to implement a focused, restricted exam protocol and report for cardio-oncology LVEF screening, or to provide oncologists with a list of echo findings that should prompt formal cardiology referral.

Conclusion

In the absence of a dedicated cardio-oncology service, cancer specialists have to cope with significant uncertainties regarding the findings on echocardiography reports. Their response to echo findings is non-standardised and inhomogeneous. Therefore, a formalised pathway for clinical clarification of echocardiographic findings for the non-cardiologist is required

Key messages

- Oncologists demonstrate limited confidence in interpreting echocardiography reports, particularly with specialised terminology and parameters

- Clinical responses to common echocardiographic findings are heterogeneous, reflecting the absence of standardised guidance

- Implementation of dedicated cardio-oncology pathways or structured interpretive frameworks could improve clarity, reduce unnecessary referrals, and enhance patient outcomes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Local Health Board Governance Committee.

References

1. Abdul-Rahman T, Dunham A, Huang H et al. Chemotherapy induced cardiotoxicity: a state of the art review on general mechanisms, prevention, treatment and recent advances in novel therapeutics. Curr Probl Cardiol 2023;48:101591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101591

2. Han X, Zhou Y, Liu W. Precision cardio-oncology: understanding the cardiotoxicity of cancer therapy. NPJ Precis Oncol 2017;1:31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-017-0034-x

3. Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS et al. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J 2022;43:4229–361. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac244

4. Robinson S, Rana B, Oxborough D et al. A practical guideline for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram in adults: the British Society of Echocardiography minimum dataset. Echo Res Pract 2020;7:G59–G93. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERP-20-0026

5. Bansal M, Sengupta PT. How to interpret an echocardiography report (for the non-imager)? Heart 2017;103;1733–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309443

6. Andres MS, Pan J, Lyon AR. What does a cardio-oncology service offer to the oncologist and the haematologist? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2021;33:483–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2021.03.012

7. Andres M, Murphy T, Poku N et al. The United Kingdom’s first cardio-oncology service: a decade of growth and evolution. JACC CardioOncol 2024;6:310–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccao.2023.12.003