Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in young athletes is a rare but devastating event, most often caused by structural or electrical abnormalities of the heart. Although athletes are generally among the healthiest individuals, the occurrence of SCD in this group attracts significant public attention, particularly as exercise may trigger fatal events in those with underlying disease. This has driven debate around the role of pre-participation screening (PPS) as a strategy to identify at-risk individuals before they compete. Several international sporting and scientific organisations have issued recommendations, but screening protocols vary, and the balance between benefit, feasibility, cost, and potential harm remains controversial. While evidence suggests that screening may detect otherwise silent cardiovascular disease, limitations include false-positives, false-negatives, interpretation challenges, and the ethical implications of disqualification. This review explores the benefits and potential challenges of cardiac screening in athletes, and the implications for protecting athlete health and ensuring safe participation in sport.

Background

Sudden death in young adults is a highly devastating and tragic event. The majority of sudden deaths in young individuals can be attributed to cardiac causes as a result of abnormalities in either cardiac structure or electrical system. The large body of evidence concerning sudden cardiac death (SCD) has been evaluated in young competitive athletes. Indeed, this demographic are more at risk as intensive exercise may be a trigger for SCD in those with underlying cardiac disease.1 Additionally, sudden deaths in young athletes are often high profile and raise significant media awareness. Estimates of incidence of SCD in athletes seem to vary widely, but rates as high as 1:23,000 have been observed.2 Early identification of those at risk of SCD has beneficial prognostic indications, as lifestyle modifications, pharmacological therapies, ablation procedures and implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICD) can be offered.

Several international scientific and sporting bodies have recommended pre-participation cardiac screening (PPS) including the European society of Cardiology (ESC),3 American Heart Association (AHA),4 and the International Olympic Committee (IOC).5 However, there are still some barriers for universal PPS implementation, such as cost-effectiveness, reliability and ethical concerns. This review aims to provide a balanced overview of the state of cardiac screening globally, exploring the benefits and potential limitations.

Aetiology of SCD in young athletes

SCD is the leading cause of non-accidental death in athletes and, therefore, represents a significant public health concern.6 SCD in young athletes is most commonly attributable to structural or functional cardiac abnormalities, or to primary arrhythmic disorders.7 Understanding of the causes of SCD has evolved considerably over the past few decades. Initially, structural cardiomyopathies, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), were thought to be the leading cause of SCD, especially in the US.8 In Italy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), a condition where there is pro-arrhythmic fibrous fatty infiltration within the right ventricle, has been reported as the most common cause of SCD.1 More recently, a nationwide autopsy database study in the UK, highlighted that 53% of deaths could be attributed to sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS), a primary arrhythmia syndrome characterised by a morphologically structurally normal heart.9 Predominant entities, which make up SADS, include the ion channelopathies, such as Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome (LQTS) and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT).10,11

Screening protocols

Various sports and cardiovascular organisations advocate for cardiac screening, however, there are variations in the screening protocols suggested. Both Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) and the IOC recommend a PPS protocol consisting of a history and physical examination and resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG).5,12 Both organisations do not recommend further testing with non-invasive imaging unless abnormalities are detected. Unique to the FIFA guidance, was the suggestion that all football athletes ≥12 years old should undergo PPS. Despite the fact that there is limited evidence for screening in those <18 years old, observational data suggest that athletic schoolchildren are at a four-times higher risk of SCD compared with their non-athletic counterparts.13

Types of cardiac screening

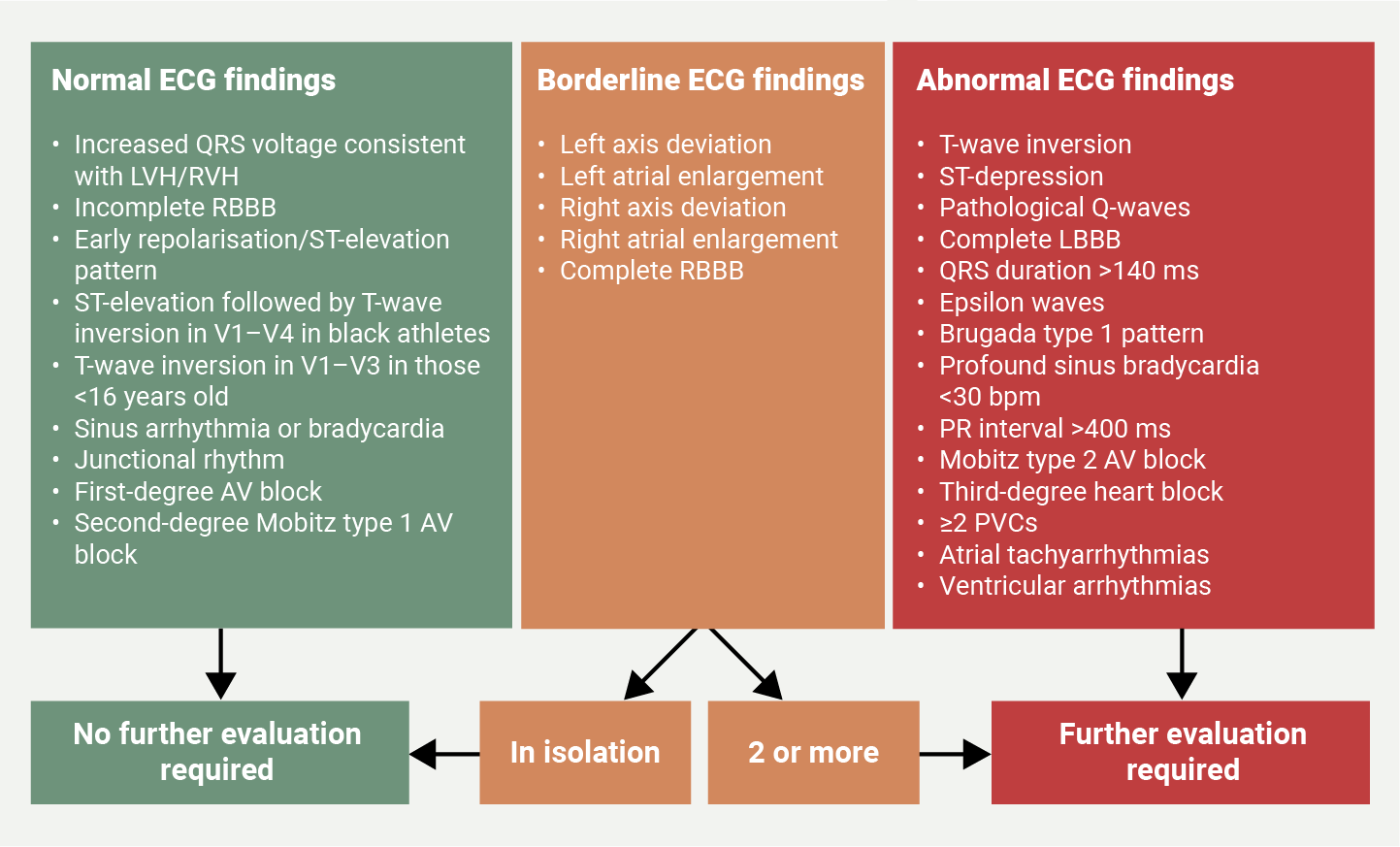

The components of cardiac screening are highly heterogenous, and the recommendations of particular screening modalities seem to vary between international organisations. There is often a balance between availability, cost-effectiveness, false-positive and false-negative rates. The least invasive form of PPS is a history and physical examination (H&P). The components of a H&P are well summarised in the 14-element questionnaire, and include a thorough history of red flag symptoms, family history and physical examination. The AHA general recommendation for young athletes is for H&P to be the only initial screening modality.4 The exclusion of ECG within the initial screening was primarily due to the large number of young athletes with a relatively low national incidence of SCD, alongside false-negative/positive results, large variation in observer variability and cost-effectiveness concerns. A 2017 survey evaluating the use of ECGs for PPS, found that 92% of paediatricians did not include an ECG due to the above guidance, and furthermore, only 37% felt confident to interpret an adolescent ECG.14 This highlights the impact of observer variability and expertise for accurately identifying ECG changes that are indicative of conditions associated with SCD. However, one systematic review by Harmon et al. comparing the effectiveness of ECG and H&P PPS found the sensitivity and specificity of ECG screening to be far superior to both H&P (sensitivity/specificity 94%/93% ECG, 20%/94% history, 9%/97% physical examination).15 More recently, a meta-analysis built upon the findings of Harmon et al. by also including studies that used the AHA 2015 international screening criteria, and found that ECG screening was significantly associated with detection of cardiac disease, while H&P was not. Furthermore, ECG screening was even more effective at detecting conditions associated with SCD with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.0 using ECG screening versus 1.05 with H&P.16 In contrast to AHA guidance, the ESC advocates for the addition of ECG alongside H&P in the initial screening of young athletes, citing the low sensitivity of history questionnaires and the consistent outperformance of ECG screening. Specific ECG criteria have been proposed for athletes, as certain changes may be mislabelled as pathological, despite being secondary to physiological adaptions of cardiovascular structure. Figure 1 summarises normal, borderline and abnormal ECG criteria for young athletes.

| Key: AV = atrioventricular; ECG = electrocardiogram; LBBB = left-bundle branch block; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; PVC = premature ventricular complex; RBBB = right-bundle branch block; RVH = right ventricular hypertrophy Adapted from: Oxborough D, George K, Cooper R et al. Echocardiography in the cardiac assessment of young athletes: a 2025 guideline from the British Society of Echocardiography (endorsed by Cardiac Risk in the Young). Echo Res Pract 2025;12:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44156-025-00069-0 |

Echocardiography is a non-invasive tool that can be used to quantify cardiovascular structure and function, and can increase the sensitivity of PPS when compared with ECG or H&P, albeit as a more costly and less accessible PSS modality. Currently, echocardiography is recommended as a secondary investigation for further work-up in the presence of initial abnormalities on H&P or ECG. However, an estimated 30% of causes of SCD, including congenital coronary anomalies and 10–20% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, cannot be identified by ECG, especially in the asymptomatic period when athletes undergo PPS.17,18 Studies have suggested an additional 4.5% increase in diagnostic yield in young athletes with the addition of echocardiography.19 However, in young professional athletes there are physiological adaptions in cardiovascular structure, which are often challenging to differentiate from pathological changes using echocardiography. Therefore, in these cases, athletes may benefit from further investigation with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and stress imaging.20

Outcomes of cardiac screening

The Italian experience

The success of cardiac screening has primarily been observed within the Italian cohort. PPS is considered mandatory in all athletes in Italy by law, and consists of H&P and resting 12-lead ECG. Corrado et al. described a landmark study comparing the incidence of SCD in the pre-screening period and the late screening period in over 40,000 athletes in the Veneto region of Italy over a 26-year follow up.21 The study found that the annual incidence of SCD reduced by 90% (from 3.6/100,000 person-years in 1979–1980 to 0.4/100,000 person-years in 2003–2004) from the pre-screening period to the late screening period. Additionally, mortality reduction was predominantly due to the increased identification of cardiomyopathies at PPS. More recently, Corrado and colleagues evaluated incidence of SCD in younger athletes aged 7–18 years over 2008–2019 in the Veneto region and found that there were no cases of SCD after a median follow-up of 7.5 ± 3.7 years, even among athletes who were disqualified due to a new cardiovascular diagnosis.22 This highlights the success of early detection through PPS among young athletes.

Influence on future interventions

Early detection can lead to an individualised and tailored approach to management, and can include lifestyle interventions, such as sports restriction, or the avoidance of competitive sport entirely. In a nationwide screening programme of young individuals in the UK, Dhutia et al. demonstrated that more than 50% of individuals identified with cardiovascular disease via screening received prognostic interventions beyond lifestyle advice.23 Moreover, the fact that most individuals who received medical intervention were asymptomatic, and identified solely on the basis of an abnormal ECG, underscores the value of inclusion of the ECG in detecting occult disease, and enabling early treatment that could significantly extend lifespan.

Psychological impact of screening

The psychological impact of PPS on athletes must not be overlooked when evaluating effective screening strategies. On one hand, a negative PPS can result in peace of mind for both athletes and families, and can alleviate pre-participation anxiety. However, the fear of positive or false-positive PPS results can result in worry about the athlete’s future health and potential disqualification from competitive sport. Hill et al. evaluated the psychological impact of PPS and found that athletes who tested false-positive had no greater measurable anxiety than those with normal screening results, both during and after the screening protocol.24 Understandably, for those who had true-positive screening, results exhibited psychological distress and anxiety, and they should receive support and psychological intervention. Asif et al. echoed similar findings in athletes who underwent isolated ECG screening.25 Athletes who received a false-positive ECG screen, did not experience greater anxiety than those who received a normal screen, but did experience greater worry surrounding sports disqualification. Those with false-positive ECG screens were also more likely to recommend ECG screening for all athletes and felt significantly safer in athletics, suggesting a positive impact on training.

In summary, evidence suggests that the perceived negative psychological impact of PPS is limited and, therefore, should not be used as a major deciding factor on whether PPS is implemented. Instead, screening should be used to raise awareness of cardiovascular disease and promote safe exercise.

Family implications

A diagnosis made via PPS, while distressing, can lead to a full family screening protocol, thus, leading to the identification of further potential family members with an inherited cardiac condition.8,9,26 This can lead to earlier identification of other affected asymptomatic family members, which can result in earlier initiation of treatment. Identification of an inherited cardiac condition can also allow for genetic counselling and family planning discussions, in order to make athletes and families aware of the potential risk of future offspring being affected.

Potential limitations of cardiac screening

There are some valid limitations to ECG screening, and this has led to associations, such as the AHA, not recommending its use in PPS. It has been stated that ECG screening may be high cost, have low inter-observer reliability and incurs a not insignificant false-positive rate, leading to subsequent inappropriate secondary testing.

False-positive rates

It is recognised that individuals participating in intensive exercise can develop a constellation of physiological alterations in autonomic tone, cardiac structure and cardiac function, which may be represented by electrical anomalies on the ECG. These electrical alterations related to athletic conditioning can overlap with those observed in individuals with cardiovascular disease. This conundrum is encountered more frequently in male athletes, athletes of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity, and in athletes participating in endurance disciplines.27–29 Misinterpretation of these benign physiological training-related ECG changes is not uncommon and had been cited as a major limitation of ECG screening, primarily due to the need for costly downstream investigations and erroneous disqualification from sport.

However, evolution of ECG interpretation criteria derived from evidence-based dissection of the athletes’ ECG, have sequentially reduced the false-positive rates of ECG screening. Application of the latest iteration, the 2017 international ECG criteria, has reduced the rate of athletes warranting additional investigation due to ECG abnormalities to 3%,30 representing an impressive 30% relative reduction versus the original 2010 ESC guidelines, without compromising the ability to detect athletes with serious cardiac disease.30

False-negative rates

PPS programmes, with or without ECG, cannot detect all disorders predisposing to SCD in athletes; for example, the ECG is normal and, therefore, unable to identify the majority (>90%) of individuals with premature coronary artery disease or congenital coronary anomalies.31 Furthermore, the ECG may be normal in 5–10% of athletes with HCM and in 25–30% of genetically affected individuals with LQTS.32 Similarly, the resting ECG is usually normal in individuals with CPVT.33

Variation in ECG interpretation

As with any subjective investigation, the effectiveness of the ECG as a PPS tool is dependent on the individual interpretation of the test. A study of ECG interpretation in 400 highly trained athletes revealed that cardiologists less familiar with the athletes’ ECG were at least 40% more likely to categorise ECGs as abnormal, compared with experienced cardiologists.34 Even among cardiologists experienced in ECG interpretation, in athletes, inter-observer agreement was moderate at best. This limitation highlights the need for greater focus on physician education, training and accreditation, and practical experience to improve the accuracy and reproducibility of ECG screening in athletes.

Integration of artificial intelligence for interpretation of ECGs in athletes is promising, and is likely to revolutionise how we approach cardiovascular screening by improving the diagnostic accuracy and efficiency – and ultimately enhance both clinical and economic outcomes.35

Cost

One of the biggest criticisms of PPS is the large cost associated with screening a population where the absolute event rate of SCD is relatively low. The cost associated with screening has undoubtedly limited PPS for athletes participating at the highest echelons of sport, under the banner of financially endowed organisations. Cost-effectiveness studies from the US have reported the cost per athlete life saved to range from $44,000 to $204,000, with the variation being explained by differences in methodology, including prevalence of disease and cost of investigations. While the ECG is a relatively cheap test, there are concerns about the costs of any additional investigations required following screening to confirm or refute the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease.23,36–39 In a study of nearly 5,000 young athletes from 26 different sporting disciplines in the UK, modification of ECG interpretation criteria with the international recommendations was associated with significant reductions in the proportion of secondary investigations following PPS, with subsequent reductions in the overall cost of ECG screening by nearly 25%, without compromising the ability to identify serious cardiac disease.30,38 Such data are likely to make screening more attractive and feasible to other sporting organisations.

Screening frequency

There is substantial global variation in PPS protocols, particularly regarding the use of one-off versus serial cardiovascular assessments. The Italian PPS programme mandates for an annual medical evaluation and ECG screen.40 A study evaluating serial screening, in line with the Italian PPS protocol, in a cohort of young athletes reported that 64% of cardiovascular disease diagnoses were made during sequential screening evaluations over an 11-year period, having been missed on initial screening. Disease detection in this study was largely accounted for by cardiomyopathies, ion channelopathies and congenital anomalous coronary arteries, suggesting that many young athletes with cardiovascular disease demonstrate greater penetrance of overt phenotypic features with advancing age and/or pubertal development.22 Therefore, organisations planning PPS should ensure that there is a sustainable programme in place to deliver sequential screenings for their athletes.

Interpretation challenges

Diagnostic challenges can occur in athletes due to physiological adaptions to exercise causing similar cardiovascular structural and electrical changes seen in pathological disease. Vigorous exercise, typically in the form of endurance with some resistance training, can result in left ventricular (LV) wall thickening, increased ventricular chamber sizes, with preserved systolic function seen in echocardiography – changes more commonly referred to as ‘athletes’ heart’.41 Especially in black athletes, there is often increased wall thickness up to 15 mm, which is a similar thickness to that seen in those with mild HCM.42 Likewise, physiological right ventricular (RV) dilation, QTc prolongation and J-point elevation with T-wave inversion, can mimic changes seen in ARVC, LQTS and Brugada type 1 pattern, respectively.41,43–45 As a result, there can often be diagnostic difficulty, even when utilising a combination of H&P, ECG and echocardiography PPS, and athletes with borderline findings may require further stress testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which would significantly impair the cost-effectiveness of PPS.

Ethical dilemma

Ethics, law and regulation surrounding cardiovascular screening is complex and multi-faceted. Screening represents an opportunity to detect potentially lethal cardiovascular diseases, but it is often mandated and reserved for competitive athletes. A significant proportion of students and young collegiate individuals may not engage in competitive sports, but still participate in vigorous physical activity. Limiting screening programmes to competitive athletes excludes this cohort from potential cardiovascular evaluation.46

On the other hand, there are ethical dilemmas with regards to mandatory cardiovascular screening, especially given the stringent participation criteria among many sports organisations. Mandatory PPS may lead to false-positives, resulting in inappropriate disqualification from competitive sports. This can significantly negatively impact an athlete’s career, and may result in significant psychological distress to individuals. Indeed, this was a worry shared among athletes who had false-positive ECG screens in Asif et al.’s 2017 study.25

Conclusion

Prevention of SCD in young athletes is paramount and it forms the cornerstone of sports cardiology research. The introduction of more well-refined and rigorous ECG criteria, as well as a better understanding of how exercise physiologically affects the heart, have redefined the role of cardiac screening within this demographic. Rates of false-positives have dropped drastically over the past decade, and modern-day PPS is now at a point where it is regarded as both feasible and cost-effective in many healthcare systems globally. There is evidence to suggest that early identification in the asymptomatic stage has been shown to reduce the incidence of SCD, possibly through the initiation of specific therapies and providing the correct exercise advice.21

Key messages

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)-based pre-participation screening (PPS) detects up to 94% of athletes with underlying cardiovascular disease, outperforming history (20%) and physical examination (9%)

- Serial screening identifies 64% of cardiovascular diagnoses that are missed on initial evaluation

- Updated international ECG criteria reduce false-positives and unnecessary follow-up investigations to approximately 3%

- Early detection through PPS enables timely interventions and facilitates family screening for inherited cardiac conditions

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Editors’ note

This is the fourth article in our sports cardiology series. See previous articles by Cox https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2025.016; Westaby https://doi.org/10/5837/bjc.2025.019; and Petrone https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2025.030

References

1. Corrado D, Basso C, Rizzoli G, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Does sports activity enhance the risk of sudden death in adolescents and young adults? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1959–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2003.03.002

2. Drezner JA, Rao AL, Heistand J, Bloomingdale MK, Harmon KG. Effectiveness of emergency response planning for sudden cardiac arrest in United States high schools with automated external defibrillators. Circulation 2009;120:518–25. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.855890

3. Corrado D, Pelliccia A, Heidbuchel H et al. Recommendations for interpretation of 12-lead electrocardiogram in the athlete. Eur Heart J 2010;31:243–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp473

4. Maron BJ, Levine BD, Washington RL, Baggish AL, Kovacs RJ, Maron MS. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. Task force 2: preparticipation screening for cardiovascular disease in competitive athletes. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:2356–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.034

5. Ljungqvist A, Jenoure P, Engebretsen L et al. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on periodic health evaluation of elite athletes March 2009. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:631–43. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.064394

6. Harmon KG, Asif IM, Klossner D, Drezner JA. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes. Circulation 2011;123:1594–600. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.004622

7. Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Robertus JL et al. Etiology of sudden death in sports: insights from a United Kingdom regional registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2108–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.062

8. Maron BJ, Haas TS, Ahluwalia A, Rutten-Ramos SC. Incidence of cardiovascular sudden deaths in Minnesota high school athletes. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:374–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.11.024

9. Sheppard MN, Westaby J, Zullo E, Fernandez BVE, Cox S, Cox A. Sudden arrhythmic death and cardiomyopathy are important causes of sudden cardiac death in the UK: results from a national coronial autopsy database. Histopathology 2023;82:1056–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14889

10. Lahrouchi N, Raju H, Lodder EM et al. Utility of post-mortem genetic testing in cases of sudden arrhythmic death syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:2134–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.046

11. Behr ER, Dalageorgou C, Christiansen M et al. Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome: familial evaluation identifies inheritable heart disease in the majority of families. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1670–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehn219

12. Baggish AL, Borjesson M, Pieles GE et al. Recommendations for cardiac screening and emergency action planning in youth football: a FIFA consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 2025;59:751–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2025-109751

13. Toresdahl BG, Rao AL, Harmon KG, Drezner JA. Incidence of sudden cardiac arrest in high school student athletes on school campus. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:1190–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.017

14. Patel A, Webster G, Ward K, Lantos J. A survey of paediatricians on the use of electrocardiogram for pre-participation sports screening. Cardiol Young 2017;27:884–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951116001529

15. Harmon KG, Zigman M, Drezner JA. The effectiveness of screening history, physical exam, and ECG to detect potentially lethal cardiac disorders in athletes: a systematic review/meta-analysis. J Electrocardiol 2015;48:329–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.02.001

16. Goff NK, Hutchinson A, Koek W, Kamat D. Meta-analysis on the effectiveness of ECG screening for conditions related to sudden cardiac death in young athletes. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2023;62:1158–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/00099228231152857

17. Maron BJ, Doerer JJ, Haas TS, Tierney DM, Mueller FO. Sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: analysis of 1866 deaths in the United States, 1980–2006. Circulation 2009;119:1085–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804617

18. Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E et al. Significance of false negative electrocardiograms in preparticipation screening of athletes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1027–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.035

19. Maurizi N, Baldi M, Castelletti S et al. Age-dependent diagnostic yield of echocardiography as a second-line diagnostic investigation in athletes with abnormalities at preparticipation screening. J Cardiovasc Med 2021;22:759–66. https://doi.org/10.2459/JCM.0000000000001215

20. Millar LM, Fanton Z, Finocchiaro G et al. Differentiation between athlete’s heart and dilated cardiomyopathy in athletic individuals. Heart 2020;106:1059–65. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2019-316147

21. Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, Michieli P, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA 2006;296:1593–601. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.13.1593

22. Sarto P, Zorzi A, Merlo L et al. Value of screening for the risk of sudden cardiac death in young competitive athletes. Eur Heart J 2023;44:1084–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad017

23. Dhutia H, Malhotra A, Finocchiaro G et al. Diagnostic yield and financial implications of a nationwide electrocardiographic screening programme to detect cardiac disease in the young. EP Europace 2021;23:1295–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euab021

24. Hill B, Grubic N, Williamson M et al. Does cardiovascular preparticipation screening cause psychological distress in athletes? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2023;57:172–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-105918

25. Asif IM, Annett S, Ewing JA et al. Psychological impact of electrocardiogram screening in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1489–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097909

26. Silajdzija E, Vissing CR, Christensen EB et al. Family screening in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: identification of relatives with low yield from systematic follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;84:1854–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.08.011

27. Papadakis M, Carre F, Kervio G et al. The prevalence, distribution, and clinical outcomes of electrocardiographic repolarization patterns in male athletes of African/Afro-Caribbean origin. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2304–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr140

28. Abergel E, Chatellier G, Hagege AA et al. Serial left ventricular adaptations in world-class professional cyclists: implications for disease screening and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:144–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.057

29. Pelliccia A, Culasso F, Di Paolo FM, Maron BJ. Physiologic left ventricular cavity dilatation in elite athletes. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:23–31. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-1-199901050-00005

30. Dhutia H, Malhotra A, Finocchiaro G et al. Impact of the International recommendations for electrocardiographic interpretation on cardiovascular screening in young athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:805–07. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.018

31. Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Kligfield P et al. Assessment of the 12-lead ECG as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12–25 years of age): a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2014;130:1303–34. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000025

32. Sheikh N, Papadakis M, Schnell F et al. Clinical profile of athletes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:e003454. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.003454

33. Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M et al. Executive summary: HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Europace 2013;15:1389–406. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eut272

34. Dhutia H, Malhotra A, Yeo TJ et al. Inter-rater reliability and downstream financial implications of electrocardiography screening in young athletes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:e003306. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003306

35. Armoundas AA, Narayan SM, Arnett DK et al. Use of artificial intelligence in improving outcomes in heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024;149:e1028–e1050. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001201

36. Malhotra R, West JJ, Dent J et al. Cost and yield of adding electrocardiography to history and physical in screening Division I intercollegiate athletes: a 5-year experience. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:721–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.12.024

37. Schoenbaum M, Denchev P, Vitiello B, Kaltman JR. Economic evaluation of strategies to reduce sudden cardiac death in young athletes. Pediatrics 2012;130:e380–e389. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3241

38. Dhutia H, Malhotra A, Gabus V et al. Cost implications of using different ECG criteria for screening young athletes in the United Kingdom. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:702–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.076

39. Menafoglio A, Di Valentino M, Segatto JM et al. Costs and yield of a 15-month preparticipation cardiovascular examination with ECG in 1070 young athletes in Switzerland: implications for routine ECG screening. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1157–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092929

40. Vessella T, Zorzi A, Merlo L et al. The Italian preparticipation evaluation programme: diagnostic yield, rate of disqualification and cost analysis. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:231–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100293

41. Finocchiaro G, Westaby J, Sheppard MN, Papadakis M, Sharma S. Sudden cardiac death in young athletes: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;83:350–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.10.032

42. Di Paolo FM, Schmied C, Zerguini YA et al. The athlete’s heart in adolescent Africans: an electrocardiographic and echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1029–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.008

43. Zaidi A, Sheikh N, Jongman JK et al. Clinical differentiation between physiological remodeling and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in athletes with marked electrocardiographic repolarization anomalies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2702–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.035

44. Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Dhutia H et al. Electrocardiographic differentiation between ‘benign T-wave inversion’ and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. EP Europace 2018;21:332–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euy179

45. Basavarajaiah S, Wilson M, Whyte G, Shah A, Behr E, Sharma S. Prevalence and significance of an isolated long QT interval in elite athletes. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2944–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm404

46. Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Caplan A. Ethics of preparticipation cardiovascular screening for athletes. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:375–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2015.21