The use of drug-eluting stents (DES) has increased exponentially in recent years. There appears to be little difference in short- to medium-term safety compared with bare-metal stenting (BMS). Coronary thrombosis after stent implantation is well recognised, resulting in acute myocardial infarction and not uncommonly in death. Late (>6 months) stent thrombosis is rare with BMS, but there is a concern that DES might be susceptible to thrombosis due to delayed endothelialisation.

The prolonged use of dual antiplatelet therapy (APT) with aspirin plus a thienopyridine (e.g. clopidogrel) is recommended. The premature discontinuation of APT in patients with DES without consultation with the treating cardiologist can result in stent thrombosis and adverse outcome.

Introduction

The use of drug-eluting stents (DES) has increased exponentially in recent years with a significant improvement in the rates of re-stenosis, target lesion and target vessel revascularisation.1-3 There appears to be little difference in short- to medium-term safety compared with bare metal stenting (BMS).4 Coronary thrombosis after stent implantation is well recognised, resulting in acute myocardial infarction and marked adverse outcome. Typically, it happens in the first 3–10 days after the procedure leading almost always to an acute myocardial infarction and not uncommonly to death. Late (>6 months) stent thrombosis is rare with BMS, but there is a concern that DES might be susceptible to thrombosis due to delayed endothelialisation.5,6

The prolonged use of dual antiplatelet therapy (APT) with aspirin plus a thienopyridine, usually clopidogrel, is recommended. In addition, optimal stent deployment at high pressure helps to reduce the likelihood of stent thrombosis. The premature discontinuation of APT in patients with DES, without consultation with the treating cardiologist, can result in stent thrombosis and adverse outcome.

We present two cases of DES thrombosis with resulting acute myocardial infarction following the premature discontinuation of APT.

Case 1

A 70-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic atrial fibrillation treated with warfarin, underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to the left anterior descending (LAD)/diagonal bifurcation with sirolimus DES with good angiographic results.

He was discharged home on dual APT with aspirin and clopidogrel with a plan to stop his aspirin in three months, restart warfarin, and then continue long term on a combination of clopidogrel and warfarin.

He was admitted again to a peripheral hospital four weeks later with increasing shortness of breath and was found to be in fast atrial fibrillation. His aspirin and clopidogrel were stopped and he was commenced on warfarin. Ten days later he developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding and was transfused with two units of blood in addition to vitamin K. Gastroscopy showed two gastric ulcers. Two days later he developed central chest pain with acute anterior ST elevation myocardial infarct and he was transferred to our centre for primary angioplasty.

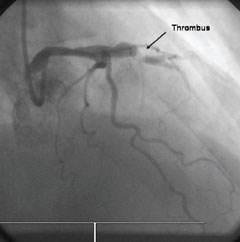

Repeat coronary angiography showed an occluded LAD with evidence of a thrombus at the site of stenting (figure 1). The occlusion was traversed with a 0.014 BMW angioplasty wire and the area dilated with an angioplasty balloon restoring a normal flow in the artery (figure 2) with resolution of the electrocardiogram (ECG) changes. No further stenting was undertaken. He made a steady recovery and was discharged home on dual APT with gastric protection and instruction not to stop this treatment without discussion with his cardiologist.

Case 2

A 56-year-old man with a history of smoking, hypertension and excess alcohol consumption, underwent elective PCI to his mid LAD with paclitaxel DES insertion. He was admitted three weeks later with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome and anterior ECG changes. He admitted to not taking his clopidogrel for two weeks before his admission. Repeat coronary angiography showed an occluded stent in the LAD with evidence of a thrombus. This was treated successfully with balloon angioplasty only and the importance of dual APT was re-emphasised to the patient before discharge.

Discussion

In large-scale trials, DES have shown low rates of angiographic re-stenosis of less than 10%1-3 with a target lesion revascularisation (TLR) of 3.0–4.1%.4,5 This compares favourably with BMS, where the re-stenosis rate in trials was 20–30%7,8 with a TLR of 11.3–16.6%.4,5 This reduction in the need for repeat revascularisation has led to the rapid increase in the use of DES in PCI.

Coronary thrombosis after stent implantation has become a rare (0.6–1.3%) but potentially catastrophic event resulting in myocardial infarction and not uncommonly in death (in 25–45% of cases).9 It usually occurs in the first few days after stent implantation and is often associated with undersized or inadequately expanded stents. This complication has been reduced to less than 2%, firstly by the use of optimally sized stents and deployment with high balloon pressure, and secondly by the use of dual APT with aspirin and a thienopyridine.10

BMS endothelialise within a few weeks and dual APT is usually required only for four weeks after elective procedures. This rapid endothelialisation of BMS renders late thrombosis a rare event, except after intracoronary irradiation,10 which delays the vascular healing and endothelialisation. Late thrombosis was shown, in animal studies, to be related to delayed endothelialisation caused by brachytherapy.11 It has, however, been reported in DES at up to 442 days and usually within two weeks after stopping APT.6

Stent thrombosis has not been a prominent feature in DES trials as the protocols in these trials mandated prolonged APT because delayed endothelialisation with DES was anticipated. Similar rates of stent thrombosis were reported in BMS and DES in a pooled analysis.4–12

In order to avoid this complication various issues have to be considered and adequate information should be available to medical professionals and patients alike. The treating cardiologist has to take into account all the circumstances of the patient before inserting a DES. If the patient is unlikely to be compliant with long-term APT or if the patient is likely to require a future surgical intervention that necessitates the interruption of APT, then a BMS may be preferable. This is in addition to optimal stent sizing and high-pressure deployment. If the APT has to be interrupted unexpectedly in patients with DES, protocols should be developed within cardiac networks to account for unforeseen circumstances. If surgery is required then, discussion with the cardiology team will facilitate the optimal strategy. For instance, the minimum possible period of interruption, preferably less than three to five days, and the APT started again as early as possible post-operatively. Alternatively, the surgical intervention should be postponed for at least 6–12 months to allow the maximum time possible for healing and stent endothelialisation, which in turn would reduce the risk of thrombosis.

Our knowledge about managing patients with DES is not complete. The recommended optimum duration of dual APT is 12 months. However, patients that require anticoagulation and warfarin therapy present a management challenge. In our practice, in patients who have a lesser indication for warfarin, such as patients with low- or medium-risk atrial fibrillation or previous deep vein thrombosis, we stop the warfarin for three months then we re-introduce it, stop aspirin, and continue with the combination of warfarin and clopidogrel. This is based on the fact that aspirin may predispose to gastric ulceration and higher risk of bleeding, in comparison with clopidogrel, and the lack of guidance or evidence from clinical trials. In other cases where warfarin is an absolute indication, as in patients with prosthetic cardiac valves, we treat with dual APT and warfarin keeping in mind the increased risk of bleeding. This is a contentious area and the practice varies among cardiologists.

Given the relatively new introduction of DES, many health professionals including general practitioners, dentists, and surgeons may not be aware of the need for continuous dual APT. Highlighting this important issue and its complication, as presented in our cases, should raise the awareness of stent thrombosis and the potential catastrophic outcome, which would further help to reduce the occurrence of this complication. Furthermore, patient education is also of paramount importance in insuring that the patient is empowered and in charge of continuing this dual APT without interruption, unless discussed with the cardiologist. We now provide our patients with a laminated card to carry with them. The card highlights the dual APT and the importance of continuing this combination. All this should help in reducing and hopefully preventing this uncommon but highly significant complication.

Conclusion

DES are safe and effective, and are increasingly used in the treatment of coronary artery disease. They require a prolonged period of dual APT. Premature interruption or cessation of APT may lead to stent thrombosis and in turn to myocardial infarction or even death.

All health professionals, as well as patients, should be aware of this important complication. The potential risk of stent thrombosis, with its potential serious effect, should be considered in patients with DES when discontinuation of APT is contemplated.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Drug-eluting stents are used increasingly in a wide cohort of patients

- Prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy is important with drug-eluting stents

- Early discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy may lead to stent thrombosis with resulting myocardial infarction or even death

- In cases where it is absolutely necessary to discontinue antiplatelet therapy, consultation with the treating cardiologist is important to avoid any possible complications

References

- Babapulle MN, Joseph L, Belisle P, Brophy JM. A hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. Lancet 2004;364:583–91.

- Schwartz RS, Chronos NA, Virmani R. Preclinical restenosis models and drug-eluting stents: still important, still much to learn. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:1373–85.

- McFadden EP, Stabile E, Regar E et al. Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet 2004;364:1519–21.

- Moses JW, Leon MB, Pompa JJ et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1315–23.

- Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA et al. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:221–31.

- Babapulle MN, Eisenberg MJ. Coated stents for the prevention of restenosis. Part II. Circulation 2002;106:2859–66.

- Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F et al. A comparison of balloon expandable stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med1994;331:489–95.

- Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS et al. A randomised comparison of coronary stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 1994;331:496–501.

- Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug eluting stents. JAMA 2005;293:2126–30.

- Eisenberg MJ. Drug-eluting stents: some bare facts. Lancet 2004;364:1466–7.

- Cheneau E, John MC, Fournadjiev J et al. Time course of stent endothelialisation after intravascular radiation therapy in rabbit iliac arteries. Circulation 2003;107: 2153–8.

- Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM et al. Stent thrombosis in randomised clinical trials of drug eluting stents. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1020–9.