An exploratory study with individual interviews before seeing the cardiologist, one week after the appointment, and at three-month follow-up was conducted to explore how participants’ perception and experience of heart palpitations are affected by seeing a cardiologist. Eleven of 20 participants cited anxiety as a possible cause of palpitations. A similar number were worried about their heart. After seeing the cardiologist, 7/20 participants thought something serious may have been missed, only one out of seven of whom had a clinically significant arrhythmia. It was reported that cardiologists did not address the role of psychological factors. Seven of the 20 participants still had heart-related health concerns at three months.

We conclude that many participants with palpitations without demonstrable cardiac pathology continued to experience high levels of health concern after seeing the cardiologist; this persisted at three months. The lack of resolution of the problem for these patients lay in not receiving a diagnosis or explanation. Participants reported that cardiologists did not address the possibility that psychological factors (particularly anxiety) could be relevant to the aetiology and management of palpitations. We suggest cardiologists should routinely address anxiety as a potential contributor to the cause of their patients’ symptoms.

Introduction

Palpitations present frequently in primary care, and are the second most common reason for a general practitioner (GP) to refer a patient to a cardiologist.1 Levels of distress and health concern are high in this patient group, even though most of these patients do not have demonstrable heart arrhythmias.2 Moreover, it is within this group with unexplained palpitations that psychiatric and psychological morbidity is highest.3,4 Given this background, we wondered how a patient with palpitations experienced the cardiology appointment, what effect it had on the perception of their cardiac symptoms, and whether this varied according to the presence of a cardiac diagnosis. Although there have been important and valuable descriptive studies in other areas of cardiology,5,6 a literature search did not find such a study in relation to palpitations. Two recent qualitative studies have explored similar issues for chest pain7 in which the experience of patients with cardiac or non-cardiac chest pain was improved by careful explanation, reassurance and tailored written information.

Methods

Participants were patients who had been referred by their GPs to the Cardiology Department at the Royal Sussex County Hospital because they had palpitations. All patients who were referred with this symptom were invited by letter to take part in the study at the same time as they received their cardiology appointment. The first 20 patients who agreed to take part in the study were included during a recruiting period from January 2003 to April 2004. JG, a specialist registrar in psychiatry, conducted face-to-face interviews with all participants. Each participant was interviewed three times: preceding the cardiology appointment, between one day and one week after the cardiology appointment, and at three months after. A semi-structured interview provided a framework for asking exploratory questions. Topics included illness understanding and belief, treatment expectation, level of concern, communication with professionals, and lifestyle changes. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim and analysed by using the principle of constant comparison.8,9 Analysed transcripts were coded into categories. On completion of coding, the cardiac diagnoses of participants were obtained. Analysis could then identify differences between participants with ‘benign’ and clinically significant palpitations.

Results

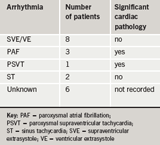

From a total of 41 patients invited, 22 agreed to take part in the study. Two participants did not complete the interviews. One participant moved house, and the other withdrew from the study. These transcripts were not included. Of the 20 participants who completed all three interviews, ages ranged from 23 to 92 years. Thirteen participants were female. A diagnosis was made in 14 out of 20 participants (table 1).

Our understanding of the participants’ experience of palpitations and the cardiology consultation is presented below as three key themes: what patients were worried about; what had been communicated by the cardiologist; and the effect of the consultation on anxiety and health concern.

Quotations are identified according to gender, study ID, age and whether symptoms are diagnosed benign (DB), diagnosed with cardiac pathology (DP) or unexplained (U). For example, M3/56/U represents third male in our study, aged 56 with unexplained symptoms.

Understanding of palpitations before seeing cardiologist

Most participants (17/20) had thoughts and ideas about why they had palpitations. Many participants gave possible external causative factors such as smoking cigarettes or drinking too much coffee, and believed that a healthy diet and exercise were protective. A minority (5/20) described some kind of intrinsically defective heart mechanism. For example:

- The nerve message…not getting through to the heart effectively, and that maybe there’s a bone pressing on a nerve (F4/49/DB).

Eleven of the 20 participants cited anxiety as a potential causal factor. Two participants linked treatment of their anxiety with a likely resolution of their symptoms:

- I thought first of all it was stress, but when it happened I was totally relaxed…well I have got a lot of stress…I am a worrying person, and maybe I absorb more subconsciously than I realise (M8/61/U)

- All my life has been stressful really…it does concern me what it’s done to me inside…I think that is…my heart reacting to what I’m feeling…it’s thumping like mad like that for the stress I’m putting it under (F7/59/DB)

- I do realise there’s got to be an element of anxiety in there…I hope it’s to do with anxiety, and then it can be treated (F11/44/DB)

- I’m wondering whether it is anxiety…I think deep down it’s the subconscious mind isn’t it…I think it’s deep down worrying, and that pain has gone now because I’ve been talking to you (F10/70/U).

Two participants contemplated whether their symptoms were physical or psychological. One participant preferred the possibility of a psychological to a physical cause:

- I’m worried that because I’ve been smoking so long that I’ve damaged something or it’s the arteries, (though) there has been a lot of stress over the last three years, and whether that’s just built up…hopefully it is something like that (F11/44/DB)

- Is there a medical reason…is there something wrong that they haven’t been able to find yet, or is it me worrying unduly about symptoms that aren’t exactly there? (M7/62/DB).

Participants’ concerns at first interview

Eight of the 20 participants with palpitations seemed relatively untroubled about their health:

- No not serious, you know it’s been seven years, I think I would have done something about it earlier, it’s a niggling sort of thing (F14/26/DB)

- Not over-concerned or worried, I just want to find out why it might be happening (F8/38/U).

Twelve of the 20 participants expressed concern about their symptoms, not infrequently mentioning fear of dying:

- You lie there thinking ‘I wonder if it’s going to stop for good’, so it is quite worrying…I think it might be serious because it’s not supposed to do that…I don’t want to die (F4/49/DB)

- He (her therapist) said like ‘what’s on the hypochondriac’s grave?’ and I said ‘what?’ and he goes ‘I told you there was something wrong!’ and I go ‘that doesn’t make me feel any better…that won’t help me when I’m in the ground!’ (F12/23/DB).

How did the cardiologist communicate an explanation to the participant?

Eleven of the 20 participants said they received an adequate explanation for their symptoms from the cardiologist. Four patients reported having electrocardiogram (ECG) confirmation of their diagnosis, and were happy that they understood their problem. For some, an explanation of a possible mechanism involving the heart was sufficient:

- He (the cardiologist) wrote out how your beat would be on an ECG…and said that’s possibly what could have happened…he said it was OK, so that was good (M6/47/DB)

- He (the cardiologist) opened the paperwork…he showed me where the blip was…and everything and it was OK. He done his best (F6/60/DB).

Despite so many participants raising the possible causal effect of anxiety before their appointment, no patient reported that the cardiologist had mentioned the role of anxiety as contributing to or being responsible for the clinical presentation. They did not however comment on this absence. Nine of the 20 participants said that their symptoms had not been adequately explained to them. Disappointment ranged from resigned acceptance to frank dissatisfaction:

- I’d been waiting so long…and I thought there would be a big revealing session…and then for nothing really to come out of it…it was almost anticlimactic…I would have thought the cardiologists, the specialists, would have been able to say things more conclusively (F12/23/DB)

- But the actual question mark hasn’t been answered, the reasons for it…it’s not made me at ease the way I expected to be if answers were given (M8/61/U).

Did seeing the cardiologist impact upon levels of anxiety?

Of 12/20 concerned participants at first interview, five were reassured after they had seen the cardiologist. They felt there had been a good and unconcerning explanation for their symptom, or that the cardiologist had not seemed concerned. Seven remaining participants remained anxious, and said that an explanation was lacking for a symptom that continued to worry them:

- So that leaves me in a bit of a quandary as to what’s going on…I’m uneasy as to what’s going on inside (M1/71/DB)

- My number one fear is that I am dying slowly and someone’s missed it…because I’m pretty young, I want to have kids in about two years, and then I start thinking ‘gosh if there is something wrong I’ve got to hurry up and do these things like stat!’…I don’t want to die…I think if I had a diagnosis then any doubts I had could at least go away (F12/23/DB).

Health concerns at the three-month interview

Seven of the 20 participants were anxious about their heart symptoms at the three-month interview. One previously worried participant was reassured, and one participant who had seemed reassured at the second interview was now worried:

- It’s not strong, but it’s a fear…what would happen if I had a heart attack and I’m out there on my own, so I tend to stick at home more and stick to the wife more, so I think there’s a part of me that’s feeling frail and feeling a bit frightened really (M6/47/DB)

- I feel there is some sort of problem, I don’t know how long I’ve had it for, but there is something there, and there’s a hereditary factor (F6/60/DB).

Relationship between cardiac diagnosis and reassurance from cardiologist

Although the number was too small for statistical analysis, three out of four participants with a significant heart condition were reassured by the cardiologist. Lack of reassurance from the cardiologist was more likely in the participants given a benign diagnosis (5/10) as opposed to those without a formal diagnosis (1/6).

Discussion

This study supports and adds detail to previous findings from quantitative research that many patients complaining of palpitations, in particular with clinically insignificant heart arrhythmias, continue to show signs of distress and health worry after seeing a cardiologist.2-4 We suggest that this may be related to patients’ perception that they do not receive an adequate explanation about the nature and cause of their symptom. Given that half of the participants with a diagnosis of benign palpitation were not reassured by the consultation, it is possible that the explanation given is too complicated to understand and/or is forgotten. Patients who did not receive a diagnosis were less likely to be concerned by their symptom than those diagnosed ‘benign’. Prior to seeing the cardiologist, most participants had suggested a putative mechanism or cause for their condition, and yet around half of them remained unclear about their diagnosis (including the role of anxiety) after the specialist appointment. At three months, we found that health concerns persisted in nearly half of our participants. Although numbers are small, there may be a correlation between not having a significant heart arrhythmia and persistent concern about palpitations.

It was reported that cardiologists did not use participants’ pre-existing thoughts that anxiety may play a part in their presentation. An explanation which helps the patient to understand his symptoms and includes the role of anxiety may make a difference, as occurred in a rapid access chest pain clinic.7 This would be a relatively simple procedure to introduce; we plan to do a follow-up study incorporating this intervention. Our written information will explain that palpitation is a key symptom of anxiety; a worried patient with palpitations may experience a worsening of their palpitations, and as either symptom can lead to worsening of the other, this could result in an escalation of severity of symptoms for both anxiety and palpitation.

In the meantime we hope our study will help cardiologists to be more open to talking about a possible psychological cause (and the potential vicious cycle of anxiety and palpitation) for their patients’ symptoms. Patients’ health beliefs are already likely to incorporate the potential role of psychological factors, particularly anxiety, and such a discussion could be reassuring. It may also direct the patient to seek more appropriate psychological help, which is likely to be through their GP. Cardiologists could also sign-post this patient group in the direction of self-help resources, e.g. booklets from the Oxford CT Centre (http://www.octc.co.uk/html/self-help.html).

A possible limitation of this study is that the 19/41 patients who chose not to take part may well have been similar to our participants but we do not know this.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who agreed to take part in this study. My thanks to Marni Freeman for her thought-provoking supervision. Ethical approval was granted by the East Sussex, Brighton and Hove Health Authority Local Research Ethics Committee.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Benign palpitations are associated with anxiety and health concern

- A lack of diagnosis or explanation will not help alleviate psychological distress in this group of patients

- A simple verbal and/or written explanation may help these patients to manage their symptoms better and more appropriately

References

- Mayou RA. Chest pain, palpitations, and panic. J Psychosomatic Res 1998;44: 55–70.

- Mayou RA, Sprigings D, Birkhead J, Price J. Characteristics of patients presenting to a cardiac clinic with palpitation. Q J Med 2003;96: 115–23.

- Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Sprigings DC, Birkhead J. Psychological and perceptual factors associated with arrhythmias and benign palpitations.Psychosomatic Med 2000;62:693–702.

- Barsky AJ. Palpitations, arrhythmias, and awareness of cardiac activity. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:832–7.

- Rogers AE, Addington-Hall JM, Abery AJ et al. Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;321:605–07.

- Tod AM, Read C, Lacey A, Abbott J. Barriers to uptake of services for coronary heart disease: qualitative study. BMJ 2001;323:214–18.

- Price JR, Mayou RA, Bass CM, Hames RJ, Sprigings D, Birkhead JS. Developing a rapid access chest pain clinic: qualitative studies of patients’ needs and experiences. J Psychosomatic Res 2005;59:237–46.

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine, 1967.

- Holliday A. Doing and writing qualitative research. London: Sage Publications, 2001.