Despite huge advances in hypertension care in recent times, some important aspects of treatment are not routinely considered in practice, in particular the need for good 24-hour blood pressure (BP) control. Insufficient access to ambulatory blood pressure monitors (ABPM) in primary care and a lack of clear guidance limits routine use in BP management.

ABPM, which measures BP over a full 24-hour period and captures BP fluctuations, may provide a more accurate reflection of patients’ ‘true’ BP than traditional office readings. Since uncontrolled 24-hour BP is linked to increased incidence of cardiovascular (CV) events and target organ damage, the panel believed the use of ABPM is beneficial to both patient and doctor. ABPM can aid compliance and guide treatment choices, given that there are marked differences in the duration of action of many commonly used BP treatments. A treatment with a long duration of action may be important in managing BP over 24 hours.

Introduction

A panel of physicians and general practitioners (GPs) with a specialist interest in cardiology was convened on 9th February 2007 in London to discuss and debate the role of 24-hour blood pressure (BP) control and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) in the management of hypertension. The panel agreed that while the UK has made huge advances in hypertension care in recent years, some important aspects of treatment are not being routinely considered in practice, in particular the need for good 24-hour BP control. Furthermore, the panel believed the use of ABPM is beneficial to both patient and doctor in aiding compliance and guiding treatment choices, but that a lack of guidance and resources currently restricts its use in the UK.

The need to treat BP consistently over 24 hours

The diagnosis of hypertension and subsequent treatment decisions tend to be made on the basis of a small number of office BP measurements taken at certain times of day. Yet hypertension is a ‘lifetime load’, affecting the body 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

During the course of 24 hours, it is normal for BP to fluctuate dramatically, starting with a rapid rise in the morning between 6 am and 10 am and falling at night (see figure 1)1. The rise in BP accompanying waking and the onset of physical activity is also associated with a rise in heart rate.

The link between the early morning BP surge and an increase in cardiovascular (CV) events is well established. Acute myocardial infarction has been shown to be three times more common at 9 am than at 11 pm2 and 44% of ischaemic strokes occur in the morning period (see Figure 2).3 BP value on rising in the morning is correlated with left ventricular mass4 and is more discriminating for association with CV events than three office readings.5

Twenty-four hour BP variability is also associated with increased target organ damage. For any given value of mean 24-hour BP, low 24-hour variability is associated with less target organ damage.8 Just as uncontrolled hypertension over a period of years will determine the extent of CV target organ damage, so it is true that BP load over 24 hours is more likely than isolated clinic measurements to predict CV disease.9

Morning BP is not the only variable that affects CV outcomes. Those patients with a night-time BP dip of less than 10%, known as non-dippers, are also at significantly increased cardiovascular risk and have an increased risk of developing left ventricular hypertrophy, target organ damage, a decline in renal function and CV events.8

There are significant challenges involved in managing early morning BP. The majority of office BP readings are taken after the early morning BP surge and therefore do not take account of the peak in BP earlier in the day. Even though office BP is controlled, many patients may still have uncontrolled early morning BP.

24-hour BP monitoring

ABPM has the advantage of measuring BP over a full 24-hour period, obtaining automatic measurements of BP at intervals throughout the day and night.10 In doing so, ABPM captures BP fluctuations, including the early morning BP surge.

ABPM is not currently recommended in the UK for diagnosing hypertension. While use of ABPM may not be appropriate in all instances, and should be used alongside office and home BP monitoring, the panel believed that 24-hour BP assessment should be used in line with the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines on measurement of blood pressure: 10

- Borderline or variable BP (>10–20 mmHg between observations or between office readings or between home/hospital/surgery readings or between repeated readings at the same sitting)

- Hypertension not responding to treatment (not at target despite a rational combination of three drugs in appropriate doses)

- Symptoms suggestive of hypotension in those on antihypertensive therapy

- Patients in whom tight control is required e.g. renal failure, diabetes

- Patients reticent to contemplate pharmacotherapy – in order to confirm risk.

Clinical practice has shown that ABPM readings are, on average, 12 mmHg systolic and 7 mmHg diastolic lower than equivalent office readings (usually rounded to 10/5 mmHg for convenience). Using machines validated by the British Hypertension Society (BHS), with correct size and fitting cuffs, the goals of treatment using ABPM suggested by the panel are a daytime mean of <130/85 mmHg, or <120/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes or renal disease or target organ damage such as left ventricular hypertrophy. A night-time mean of <120/75 mmHg was also suggested, on the basis that night-time BP may be an even better indicator of long-term prognosis than other readings.10 A key advantage of ABPM is that it is more reproducible than office BP and has been shown to be a stronger predictor of CV mortality and morbidity than office BP.10

Increasingly, patients are checking their own BP with monitors at home. If used correctly, they provide an opportunity to check BP earlier in the day. Giving free home BP monitors to patients may also be helpful in improving compliance. Asking patients to take three BP readings a day, including an early morning reading, means that a good estimation of a patient’s BP can be obtained on which to decide treatment. This can then be compared to the reading obtained in the surgery, adding 10/5 mmHg (in keeping with advice from the 2004 BHS guidelines)11 to compare the home readings with the office BP. Monitoring BP in this way also helps patients to understand that treatment is actually necessary – particularly those patients who are unwilling to start treatment. This avoids both under-treatment, and also over-treatment of patients with white-coat hypertension.

Controlling BP over 24 hours

The first approach to managing hypertension should be non-pharmacological means. Patients should be advised to lower their salt intake, reduce their alcohol consumption, lose weight and increase their exercise. For example, a >5 kg weight loss has been shown to reduce systolic BP on average by 6.63 mmHg.12

For those in whom treatment is required, using drugs in the right combination (since the majority of patients will require more than one drug) and at correct dosages was felt to be the key to successful treatment. In this respect, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)/BHS ACD algorithm, now widely adopted, has given doctors helpful guidance.13

It was agreed that use of a once-daily treatment, which controls BP over 24 hours, is needed to protect against the early morning BP surge and in order to reduce 24-hour BP variability. Additionally, given that hypertension is an asymptomatic condition, once-daily treatment may encourage patient compliance. However, there is a great deal of confusion in primary care about which treatments are for once-daily administration; even among the panel there was disagreement as to which agents were truly suitable for once-daily administration in order to deliver 24-hour control.

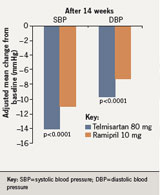

Nevertheless, it is clear that the commonly used antihypertensive therapies have different durations of action. This should be a consideration when deciding on therapy. For example, evidence from the PRISMA I study (comparing the efficacy and safety of once-daily telmisartan 80 mg and ramipril 10 mg on BP reductions over 24 hours), demonstrated that telmisartan, a long-acting angiotensin receptor blocker, is significantly more effective than ramipril at reducing BP in the early morning hours14 – the time when patients are at greatest risk of CV and cerebrovascular events.

Over 24 hours, telmisartan 80 mg produced significantly greater reductions in BP than ramipril 10 mg (a mean systolic blood pressure [SBP] reduction of 14.5 mmHg compared to 11.6 mmHg and a mean diastolic blood pressure [DBP] reduction of 9.8 mmHg compared to 7.7 mmHg, respectively) (see figure 3).14

These results are likely to have significant clinical implications given that even a small decrease in BP can produce a significant reduction in CV mortality – a 2 mmHg reduction in SBP has been shown to be associated with a 7% reduction in death from ischaemic heart disease and a 10% reduction in death from stroke.15

Guidance and policy: where are we now?

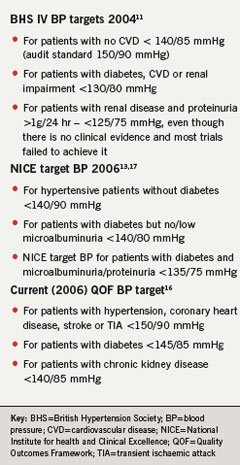

Many different guidelines exist for BP management (table 1), but much of primary care is driven by the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) agenda.16The current QOF BP target of 150/90 mmHg for patients without diabetes or chronic kidney disease does not recognise the true risk of hypertension.16 This target is in line with the BHS audit standard for those without diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD) or cardiovascular disease, and reflects the minimum recommended levels of BP control – the optimal treatment targets are lower.11

While targets are necessary, a consensus is needed on consistent, achievable targets. There is currently no target for 24-hour control and NICE does not currently recommend the routine use of ABPM in primary care.13

Targeting patients with CKD is a new clinical area in primary care. Poor control of hypertension is significantly associated with deterioration in renal function; hypertension management should be a priority in this patient population.

Conflict of interest

MM, JA, KG, GK, EK, PL and JV received honoraria for attending a consensus meeting sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim leading to the compilation of this report.

Key messages

- There is strong evidence demonstrating the importance of controlling blood pressure (BP) over 24 hours, yet this is not routinely considered when diagnosing and treating hypertension

- Uncontrolled 24-hour BP is linked to increased incidence of cardiovascular events and target organ damage

- Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) has the advantage of measuring BP over a full 24-hour period, capturing BP fluctuations which may provide a more accurate reflection of patient’s ‘true’ BP than traditional office readings

- Insufficient access to ABPM monitors in primary care and a lack of clear guidance limits the routine use of ABPM in BP management

- There are marked differences in the duration of action of many commonly used BP treatments

- Selection of a treatment with a long duration of action may be important in managing BP over 24 hours

References

- Millar-Craig MW, Bishop CN, Raftery EB. Circadian variation of blood-pressure. Lancet 1978;311:795–7.

- Muller JE, Stone PH, Turi ZG et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1315–22.

- Casetta I, Granieri E, Fallica E, la Cecilia O, Paolino E, Manfredini R. Patient demographic and clinical features and circadian variation in onset of ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol 2002;59:48–53.

- Elliott H. 24-hour blood pressure control: its relevance to cardiovascular outcomes and the importance of long-acting antihypertensive drugs. J Hum Hypertens 2004;18:539–43.

- Gosse P, Cipriano C, Bemurat L, Mas D, Lemetayer P, N’Tela G, Clementy J. Prognostic significance of blood pressure measured on rising. J Hum Hypertens 2001;15:413–17.

- Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH et al. Modifiers of timing and possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Phase II (TIMI II) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:1049–55.

- Kelly-Hayes, Wolf PA, Kase CS, Brand FN, McGuirk JM, D’Agostino RB. Temporal patterns of stroke onset. The Framingham Study. Stroke1995;26(8):1343–7.

- Mead M. The need for 24-hour blood pressure control. B J Cardiol 2003;10:310–14.

- Elliott H. The importance of 24-hour blood pressure control, Cardiology News 2005;8(3):14–15.

- O’Brien E. Practice guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension for clinic, ambulatory and self blood pressure measurement. Hypertens2005;23:697–701.

- Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ et al. British Hypertension Society. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens 2004;18:139–85.

- Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Crobbee DE, Geleijnse JM. Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.Hypertens 2003;42:878–84.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: Management of hypertension in adults in primary care. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/topic/cardiovascular/?node=7043&wordid=42 (Accessed 10 April 2007).

- Williams B, Gosse P, Lowe L, Harper R. The prospective, randomized investigation of the safety and efficacy of telmisartan versus ramipril using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (PRISMA I). J Hypertens 2006; 24(1):193–200.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360:1903–13.

- Department of Health. Quality and Outcomes Framework – Guidance 2006. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Policyandguidance/Organisationpolicy/Primarycare/Primarycarecontracting/QOF/DH_4125653 (Accessed 10 October 2007).

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Renal disease – prevention and early management. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byID&o=10914 (Accessed 6 June 2007).