A 47-year-old woman had been referred to the cardiology department with a six-month history of intermittent chest discomfort not specifically related to exertion. Her risk factors: current smoker 10–15 per day and family history of ischaemic heart disease. She had no history of diabetes or hypertension. Lipid levels had not been tested.

Her observations were recorded as heart rate 60 bpm regular, blood pressure 119/63 mmHg, jugular venous pressure was not elevated, no ankle oedema, S1 and S2 present with an apical grade 2/6 mid-systolic murmur and her chest auscultation was clear. Electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded as normal.

The patient managed to complete 10:16 minutes of a Bruce Protocol of exercise stress test (EST) with 2.1 mm of ST depression in V5 and V6. Despite the non-specificity of her symptoms and a positive EST, she was referred for a cardiac echocardiogram and cardiac catheterisation. In the interim period, she was commenced on aspirin 75 mg, simvastatin 40 mg and bisoprolol 1.25 mg.

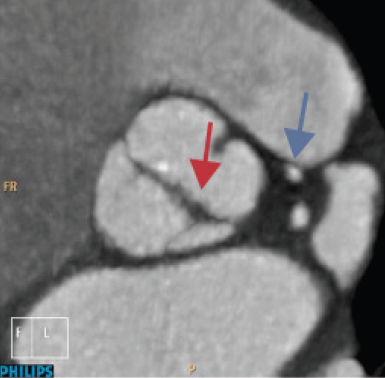

Cardiac echocardiography was performed. The aortic valve (AV) was shown to be thickened, calcified and bicuspid with mild stenosis (peak gradient 25 mmHg) with a preserved left ventricular (LV) systolic function. All other cardiac chambers and valves were within normal limits.

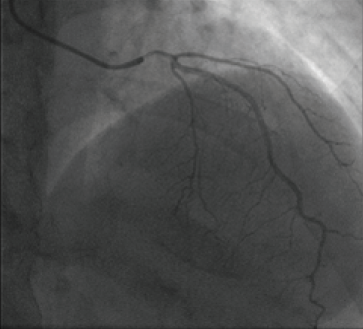

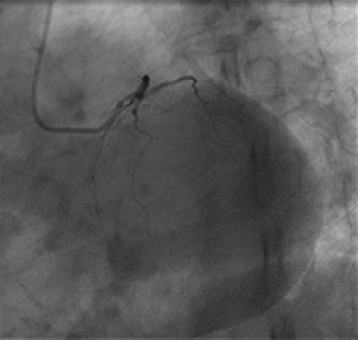

Cardiac catheterisation was performed via the right radial artery. It revealed that there was no left main stem. The left anterior descending (LAD) and circumflex (LCx) arteries were originated side by side. Intubating the LAD revealed what appeared to be an ostial narrowing in different views. The operator administered 200 µg of intra-coronary nitrate, to eliminate the possibility of catheter-induced coronary spasm. There was no drop in blood pressure when engaging the LAD artery pre- or post-nitrate. The second set of LAD images confirmed that the ostial narrowing was still severe, while the rest of the LAD was completely normal (figures 1 and 2). The LCx and the right coronary arteries (RCA) were both normal.

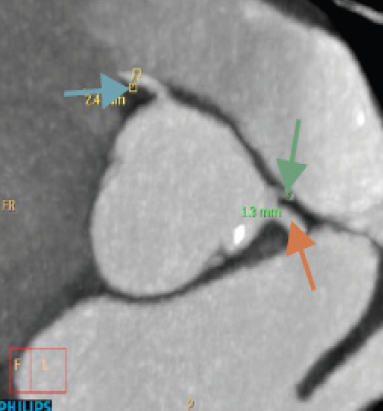

The patient was referred for a computerised tomography (CT) coronary angiogram (CTCA) for further assessment of the LAD ostium.

The CTCA corroborated the angiogram result of an absent left main stem (LMS), but side-by-side origins of the LAD and LCx arteries. The LAD was reported to have a severe ostial stenotic pinhole lesion with a diameter of 1–1.3 mm, and funnelled to 2.2 mm in the proximal vessel, with no evidence of any surrounding atherosclerotic plaque (intrinsic) (figure 3). A calcified bicuspid aortic valve was also confirmed (figure 4).

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), using a 3.0 × 15 mm Combo (OrbusNeich) drug-eluting stent, was ultimately performed to alleviate the symptoms being experienced by the patient, with positive results at 12-month follow-up.

Discussion

Ostial stenoses are frequently related to atherosclerosis. Rarer causes can be attributed to inherited anomalies. This case study is reporting a congenital LAD stenosis associated with a bicuspid aortic valve. It is presumed that it is the first reported congenital LAD stenosis associated with a bicuspid aortic valve.

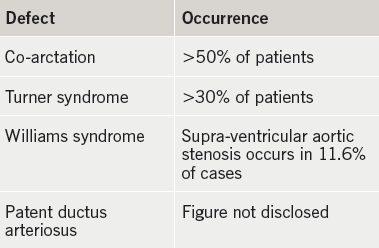

We believe this coronary anomaly to be related to the congenital development of a bicuspid aortic valve. A bicuspid aortic valve is a heart condition that is usually due to a congenital deformity. About 1–2% of the population have bicuspid aortic valves, although the condition is nearly twice as common in males. Congenital Heart Defects UK (2015) report that a bicuspid aortic valve is usually associated with several other cardiac defects (table 1).

Coronary arteries may be abnormal in bicuspid patients. A left-dominant coronary system is more commonly observed with bicuspid aortic valve. Rarely, the left coronary artery may arise anomalously from the pulmonary artery. The left main coronary artery may be up to 50% shorter in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve. Occasionally, the coronary ostium may be congenitally stenotic in association with bicuspid aortic valve.

In individuals suffering from atresia, it usually arises in the LMS, and not a specific vessel such as the LAD, the diagnosis is usually confirmed by CTCA. This patient had separate origins to the LAD and LCx. The pinhole stenosis, seen on coronary angiography and subsequently confirmed by CTCA, identified there was no atherosclerotic disease present.

Conclusion

CTCA proved an invaluable tool in endorsing the angiographic results in what is assumed to be the first reported incidence of a congenital LAD stenosis associated with a bicuspid aortic valve.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Further reading

Angelini P. Congenital coronary artery ostial disease: a spectrum of anatomic variants with different patho-physiologies and prognoses. Tex Heart Inst J 2012;39:55–9. PMCID: PMC3298900. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3298900/

Congenital Heart Defects UK. Educating and raising awareness of congenital heart defects. Website: http://www.chd-uk.co.uk/