Over and over we hear the message that healthcare spending is out of control, the National Health Service (NHS) needs to save £20 billion and that is before the baby boom* generation fully enters the most expensive part of their healthcare journey…

(*Baby boomers are noted to be between 52 and 70 years old.1)

This generation is likely to have a new set of expectations for healthcare,2 where they want to be involved, informed and in control. We know already that many go to the doctors’ surgery armed with printouts from the internet and are increasingly expecting to see more on-demand services like in every other walk of life. The chronic disease at the forefront of technology-enabled self-care is, probably, diabetes with the range of apps and gadgets increasing daily and the patients deciding for themselves which is best for their healthcare journey. What next? Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, atrial fibrillation?

With an ageing bubble of population, expectation of service improvements and ambitious cost-cutting targets, the NHS is caught in a no-win situation. This three-way crunch means inevitable disappointment whatever happens.

What’s the answer?

The temptation is to quickly point to many other industries whose cost structure has been radically altered by the application of technologies, such as the mobile phone. In banking for example, it doesn’t really matter if 100% of people use a service such as mobile banking; enough people do to significantly impact the number of bank branches, counter staff and the size of back-room support teams that are now required. This is mirrored in every other sector of our lives, except of course in the healthcare sector where in-person visits with painful wait times are the norm.

The state of near desperation does not, in itself, ensure adoption and diffusion of innovations inside the healthcare jungle. The culture of risk aversion (arguably a good thing), plus all the hard-working staff being too overloaded to even stop and think, means that things pretty much stay as they are. Is this why many start-up medical technology companies, some with innovative ideas taken from NHS settings, end up relocating to the USA rather than fighting through this treacle?

The state of near desperation does not, in itself, ensure adoption and diffusion of innovations inside the healthcare jungle. The culture of risk aversion (arguably a good thing), plus all the hard-working staff being too overloaded to even stop and think, means that things pretty much stay as they are. Is this why many start-up medical technology companies, some with innovative ideas taken from NHS settings, end up relocating to the USA rather than fighting through this treacle?

Having worked for 26 years on the border between industry and the NHS, I can attest to the first-hand experience of NHS staff being truly inspiring – so many that are eager to get on with implementation of new technology and to help with this (unfortunately glacial-paced) revolution.

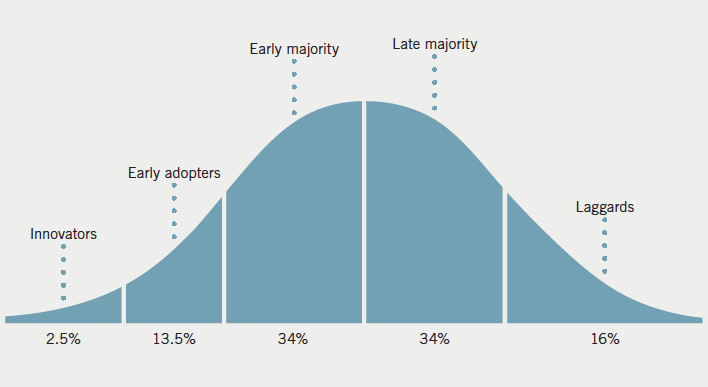

Take for example Keith, a GP from the South coast, who has taken it upon himself to fund many tools for his ‘digital doctor’s bag’ and seen the impact these can make first hand. I heard the sense of disappointment in his voice when he described how some other doctors are less than enthusiastic to immediately follow his lead. This is to be expected, however, as we know from the now famous ‘adoption curve’ that not everyone’s appetite for taking up new ideas is equal (figure 1).3

This curve is stretched out further, with much longer timelines in healthcare than in other industries, perhaps not the hundreds of years it took to adopt the stethoscope, but still longer than perhaps the state of urgency we now face would demand.

The NHS five-year forward4 view both spelled out the huge savings required and also outlined key new initiatives to embrace new pathways, approaches and technologies, such as Vanguards, Testbeds and the NHS Innovation Accelerator. These efforts to change the culture, to reinforce champions and to make adoption ‘trendy’ are to be praised and supported, in my view. As a participant in two of these initiatives I have been impressed with the passion and support for companies that do persist in trying to sell, through all the barriers, into mainstream clinical practice.

Perhaps the most encouraging output from these programmes to date has been the announcement from Simon Stevens that the NHS will provide an explicit national reimbursement route for new medtech innovations on 17 June 2016.

What about the actual technology? Can we trust it? Does it really work?

An example sentence from the Oxford Dictionary for ‘gullible’ is “an attempt to persuade a gullible public to spend their money”, and history is littered with examples of snake-oil salespeople peddling cures that, at best, use placebo, and, at worse, cause actual harm. Even back in bible times, examples were quoted, such as Luke 8:43–48 “43 Now a woman, having a flow of blood for twelve years, who had spent all her livelihood on physicians and could not be healed by any” NKJV. Stories from Silicon Valley, like that of Theranos, is so chilling that it is slated to be dramatised in a Hollywood film!5

As a result, or perhaps sometimes a reaction to this, the medical profession applies thoughtful science to the problem; assessing new drugs, surgical techniques and devices to see if they really do live up to the promises and hypotheses. This takes time and even after solid science is produced, we know that any change in clinical practice will take years and even decades to implement. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, which rightly takes into account data from large studies, is just the start of the adoption. The accelerated access review6 listed the 48 common barriers, and to overcome each takes significant effort and inevitable cost.

Large companies have learnt how to profit from this slow pace of change by making medical products, both pharmaceutical and devices, very expensive and consequently with high margins. These profits are often seen to be too much, but in the real world, they are often required to push through all the barriers to adoption, paying for large studies and employing staff to call on every clinician with the evidence.

Moving from this world of large corporates to AliveCor, I have learnt to swim the other way up the river, much like a salmon, not necessarily the easiest of journeys but one that is beginning to show signs of demonstrable progress. Getting out there with a CE (Conformité Européenne) and FDA (Food and Drugs Administration) approved medical device for less than £100 to individual users via online shops, such as Amazon, really challenged the status quo. Ex-colleagues asked if I had lost the plot; not understanding the vision of patient empowerment and moving the locus of control from the healthcare provider to the ‘consumer’ of the healthcare.

McKinsey failed to predict the popularity of cell phones, estimating in 1986 that the number of cell phones in 2000 would be one million units. It was off by 108 million units. The forecast was wrong by 10,000%. On that basis, AT&T decided to divest itself of its cell phone business.7

Healthcare will be radically different in the future, exactly how remains to be seen and you can be assured that we will look back on today’s provision with bewilderment as to how we ever lived like that.

Conflict of interest

Employed by AliveCor Ltd.

References

1. Wikipedia. Baby boomers. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baby_boomers

2. Reidbord S. Between medical paternalism and servility. Doctors empowering patients – and ourselves. Psychology Today. September 2014. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/sacramento-street-psychiatry/201409/between-medical-paternalism-and-servility

3. Wikipedia. Technology adoption lifecycle. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technology_adoption_life_cycle

4. NHS. Five year forward view. London: NHS, 2014. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

5. Lee C. Inside the Hollywood frenzy around Jennifer Lawrence’s Theranos movie. Vanity Fair. 24 June 2016. Available at: http://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2016/06/jennifer-lawrence-theranos-elizabeth-holmes

6. Taylor H. Accelerated access review: interim report. London: Department for Business, Innovation & Skills, Department of Health and Office for Life Sciences, October 2015. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/accelerated-access-review-interim-report

7. Takahashi D. Vinod Khosla says get rid of experts and invent the future you want (video). Reuters. September 2011. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/idUS90613734620110902