Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are common in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS). Our understanding of managing GI symptoms in PoTS is very limited. Our objectives were to evaluate common GI symptoms, diagnostic work-up, diagnosis and management strategy in patients with PoTS.

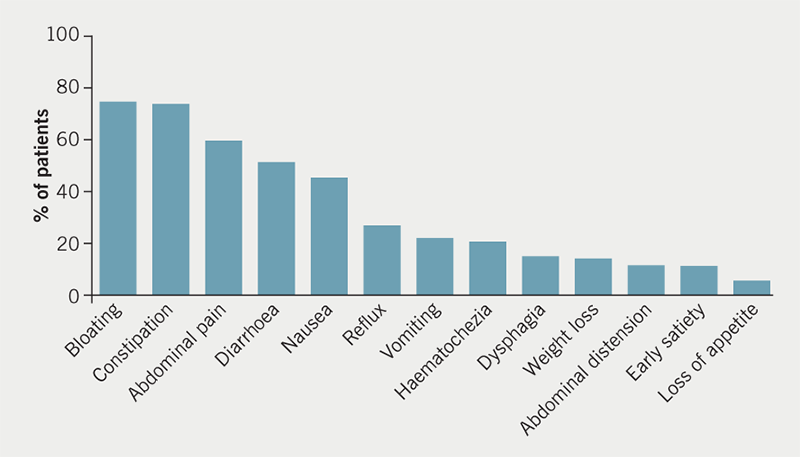

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of all patients referred to the gastroenterology clinic (2014 to 2017) with GI symptoms and known or suspected PoTS: 85 patients with PoTS and GI symptoms were seen in our clinic. Bloating (75%), constipation (74%) and abdominal pain (60%) were the most common GI symptoms. Endoscopy, high-resolution manometry, gastric-emptying studies and colonic-transit studies were commonly performed investigations. Over two-thirds of patients had confirmed or suspected GI dysmotility, 5.9% had organic GI disease (e.g. inflammatory and acid peptic disorders).

In conclusion, the majority of patients with PoTS have a functional disturbance and reduced GI motility, however, a small proportion have organic disease that needs systematic evaluation. Dietary modifications and laxatives are the main modalities of therapy.

Introduction

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) is a heterogenous group of disorders of autonomic disturbance characterised by the clinical symptoms of orthostatic intolerance, mainly light-headedness, fatigue, sweating, tremor, anxiety, palpitations, exercise intolerance and near syncope on upright posture.1 The pathogenesis is poorly understood, with various theories existing including neuropathic and autoimmune aetiologies.2 It is a condition that mainly affects young individuals, with a female preponderance. The true prevalence of PoTS is unknown, a North American study predicted that it may affect up to 170 per 100,000 individuals.3 A questionnaire-based study from the UK, which included 136 patients with PoTS, identified a high symptom burden and significant impact on quality of life.4

It is increasingly apparent that PoTS has a diverse set of manifestations outside of the cardiovascular system, including the gastrointestinal (GI) system. A survey of 28 patients with PoTS in the US focusing on GI symptoms identified that 96% reported at least one core GI symptom, and 89% reported three or more symptoms.5 Sixty-three per cent of patients had seen a gastroenterologist, 21% were diagnosed with gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying, 32% irritable bowel syndrome and 7% inflammatory bowel disease. From the UK experience, 10% of PoTS patients self-reported a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome.4

There have been a few clinical studies undertaken to delineate dysmotility of the GI tract in patients with PoTS. A study of 12 patients with PoTS and GI symptoms, subjected all patients to gastroduodenal manometry, and selected patients to further manometry and transit studies. This identified a high prevalence of abnormal manometry and radiographic features of dysmotility, including abnormal gastroduodenal manometry in 93%, and abnormal anorectal manometry in 86%.6 A large study of 163 patients with PoTS who underwent scintigraphic assessment of GI transit, identified abnormal gastric emptying in 66% of patients.7 In 15 patients with PoTS, half of whom reported GI symptoms, cutaneous electrogastrography (EGG) recorded gastric myoelectrical activity before and after a meal, and were compared with 11 healthy controls. PoTS patients were identified as having abnormal pre- and post-prandial gastric myoelectrical activity.8 In a paediatric cohort of 49 patients (half with PoTS), gastric electrical activity was found to be normal on EGG at baseline, but more abnormal in moving from supine to standing in PoTS.9 In a paediatric population of patients with GI symptoms and a tilt-table test diagnostic of orthostatic intolerance (four of 24 had PoTS), in 78% there was complete resolution of GI symptoms with treatment of orthostatic intolerance.10

We sought to characterise our experience of PoTS in terms of common GI symptoms, diagnostic work-up, final diagnosis and management strategy, in order to inform clinicians in other units who may start seeing the condition.

Method

This was a retrospective review of all patients reviewed in the gastroenterology clinic in a district general hospital with known or suspected PoTS and GI symptoms. This was the common referral pathway for a local tertiary centre cardiologist with a specialist interest in PoTS, and referrals were both local and national.

Electronic patient records, including clinic and referral letters, were reviewed for demographics, clinical information, comorbidity profile and management strategy. Radiology, endoscopy and pathology results were accessed to assess results of diagnostic investigations. The distance patients travelled from their registered home address postcode to our hospital was calculated using an online calculator. All information was collated into an electronic database. Functional GI disorder is defined as a group of symptoms arising in the mid or lower GI tract that are not due to anatomic or biochemical defects.11,12

Results

Disposition of patients and demographic features

During this time frame, 112 patients were referred to our gastroenterology clinic with suspected PoTS and GI symptoms. A total of 27 patients were excluded: 10 as they did not have evidence of PoTS following further investigation; three as it was unclear if they had confirmed PoTS; 14 did not attend their outpatient appointment or were waiting to be seen. This left 85 patients with PoTS and GI symptoms who were seen in our clinic.

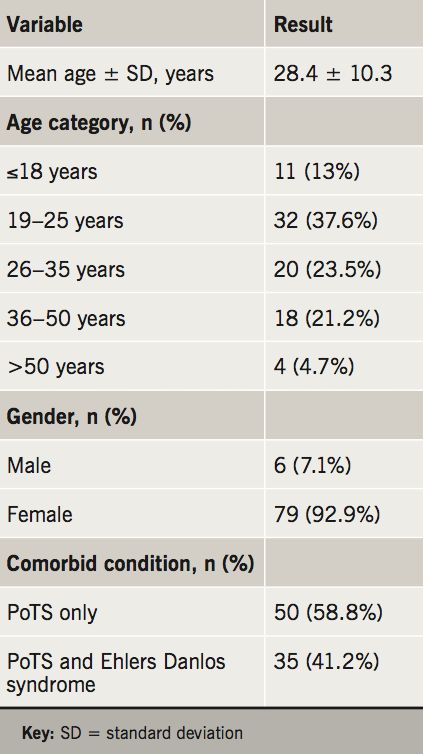

The major patient baseline characteristics are summarised in table 1. The mean age was 28.4 years (range 16–55 years), 92.9% of patients were female, and 35 (41.2%) patients had a diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. The median distance that patients travelled from their registered home address to our hospital was 16.87 miles (range 1.71 to 221 miles): 31 patients (36.5%) travelled over 20 miles to attend their appointment, including 14 (16.5%) who travelled over 50 miles.

Clinical characteristics, investigations, diagnosis and management

The range of symptoms that were reported by patients are summarised in figure 1. The most common symptoms were bloating, abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhoea, all of which were described in over 50% of patients.

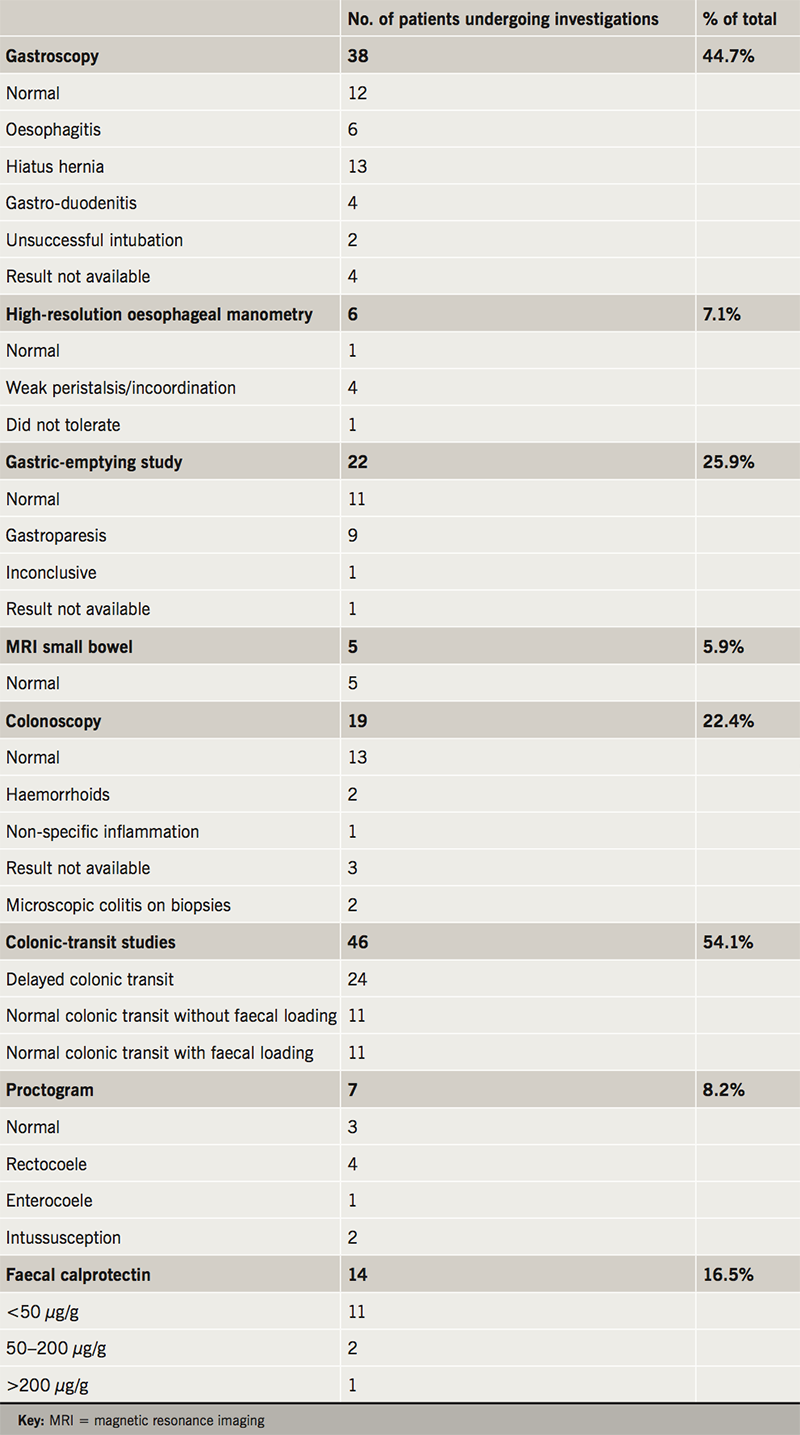

The investigations that were undertaken, either at our institution or their referring institution, are summarised in table 2. This involved a combination of investigations (e.g. gastroscopy, colonoscopy and faecal calprotectin) to look for conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, acid peptic disorder and malabsorption. Oesophageal manometry, gastric-emptying study and colonic-transit study were used to assess oesophageal, gastric and colonic dysmotility.

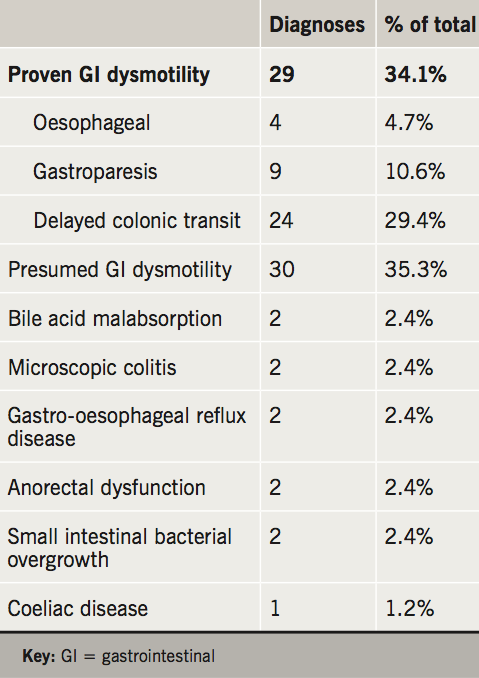

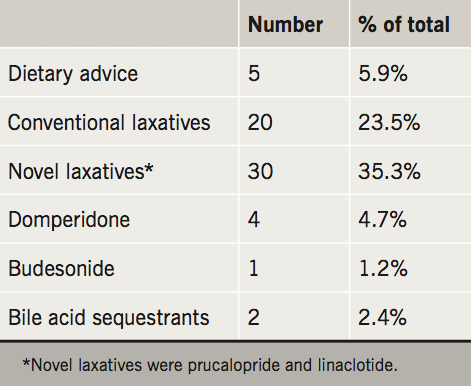

The outcome diagnoses are portrayed in table 3 and the management strategies in table 4. Related to the high prevalence of delayed colonic transit in this cohort, the majority of patients were trialled on conventional (e.g. movicol and dulcolax) or novel laxatives (e.g. prucalopride and linaclotide).

Discussion

PoTS is a condition that primarily affects young adults with a variety of symptoms encompassing a range of medical specialities. The GI symptoms and their impact on quality of life in patients with PoTS are being increasingly recognised,4 and in our series of 85 patients with PoTS we highlight the common symptoms experienced, the investigations that they have undergone in their diagnostic pathway, and present the management strategies employed in our department. We also highlight service provision for PoTS in our geographical area.

This is a young cohort of patients, as demonstrated in our study with a mean age of 28.4 years, with a range of upper and lower intestinal symptoms. Non-specific symptoms are very common, so it is important to rule out conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, acid peptic disorders and malabsorption syndromes. The most common symptoms reported by patients were constipation and abdominal pain. GI endoscopy to look for mucosal disease was performed in 44.7% to visualise the upper GI tract, and 22.4% the lower GI tract. A diagnosis of bile acid malabsorption, microscopic colitis or coeliac disease was made in 5.9% of all patients.

In keeping with previous studies on PoTS and GI symptoms, we conclude that the majority of GI symptoms can be attributed to a functional disturbance and GI dysmotility. Confirmed or suspected GI dysmotility was found in 69% of patients. The most commonly requested investigation to look for oesophageal dysmotility was high-resolution oesophageal manometry (7.1% of patients); for gastric dysmotility was radio-isotope gastric-emptying studies (25.9% of patients); and colon dysmotility was colonic-transit studies (54.1%). In total, 29 patients (34%) had evidence of GI dysmotility in the oesophagus, stomach or colon. Some patients had abnormal motility in more than one area; seven patients (24%). Of these, three had combined oesophageal and colonic dysmotility and four had combined gastric and colonic dysmotility.

A significant proportion of our patients were travelling a long distance to be seen in our service. As the recognition of PoTS increases, so will the awareness of associated GI symptoms, and the need for investigation and treatment. From our experience, laxatives were the mainstay of management, and over a third were trialled on novel laxatives (prucalopride and linaclotide). The armamentarium available to the gastroenterologist for improving GI motility is limited, however, prucalopride and linaclotide have proved very effective in the management of chronic constipation and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.13,14 In our experience, these medications are beneficial in the delayed colon transit associated with PoTS. Dietary modifications are important, and, as dietary and fluid intake can impact on cardiovascular symptoms, it is important to involve dieticians in the management of patients with PoTS.15 In line with guidance for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, patients are advised to maintain regular meals and adequate fluid intake; restrict caffeine, alcohol and fizzy drinks; limit high fibre and fresh fruit; with consideration of food avoidance or exclusion diets.16,17

There are limitations to our study. The retrospective design is subject to recall bias and confounding variables, however, a systematic evaluation of all referrals over a defined time period ensured all cases were captured. As a single-centre study the diagnosis and management is influenced by local expertise and availability of services, and, in fact, national and international practice may vary. Through years of experience in seeing patients with PoTS at our centre, an appreciation of the clinical issues and pathophysiology has developed, from which an individualised patient-centred approach has developed.

The long distances travelled to our service suggest that units with expertise or interest in GI motility disorders are limited. If that were the case then this is unsatisfactory because a high proportion of referrals to gastroenterology clinics are for disorders associated with motility disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome. We recommend an increase in awareness and training programmes for motility disorders for GI specialist trainees, as well as an increase in the service provision for motility disorders.

Conclusion

We present our cohort of 85 patients with PoTS in the UK who have been referred for investigation of GI symptoms, and demonstrate that there is a significant burden of functional GI symptoms, which may be related to abnormal myoelectrical activity and orthostatic abnormalities. Management should be focused on controlling autonomic and cardiovascular manifestations of PoTS, but also GI symptom control and dietetic involvement, with an awareness of the significant impact on these patients’ quality of life secondary to their GI symptoms.

Key messages

- Our aim was to evaluate commonly reported gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, diagnostic work-up and management and service provision for patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS)

- Approximately, two-thirds of patients with PoTS had symptoms related to GI motility and functional disorders

- Dietary modifications and laxatives are the mainstay of treatments

- Novel laxatives (prucalopride and linaclotide) are effective in managing delayed colonic transit and chronic constipation in PoTS patients

- We recommend an increase in training programmes for motility disorders for GI specialist trainees, as well as an increase in the service provision for motility disorders

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

No external funding.

Study approval

As per the NHS Research Authority tool (www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk) our study did not require ethical approval.

References

1. Agarwal AK, Garg R, Ritch A, Sarkar P. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:478–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.055046

2. Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Mayo clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:308–13. https://doi.org/10.4065/82.3.308

3. Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, Shen W-K. Postural tachycardia syndrome (PoTS). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009;20:352–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01407.x

4. McDonald C, Koshi S, Busner L, Kavi L, Newton JL. Postural tachycardia syndrome is associated with significant symptoms and functional impairment predominantly affecting young women: a UK perspective. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004127. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004127

5. Wang LB, Culbertson CJ, Deb A, Morgenshtern K, Huang H, DePold Hohler A. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Neurol Sci 2015;359:193–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.10.052

6. Huang RJ, Chun CL, Friday K, Triadafilopoulos G. Manometric abnormalities in the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a case series. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:3207–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-013-2865-9

7. Loavenbruck A, Iturrino J, Singer W et al. Disturbances of gastrointestinal transit and autonomic functions in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:92–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12480

8. Seligman WH, Low DA, Asahina M, Mathias CJ. Abnormal gastric myoelectrical activity in postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res 2013;23:73–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-012-0185-3

9. Safder S, Chelimsky TC, O’Riordan MA, Chelimsky G. Gastric electrical activity becomes abnormal in the upright position in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;51:314–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d13623

10. Sullivan SD, Hanauer J, Rowe P, Barron D, Darbari A, Oliva-Hemker M. Gastrointestinal symptoms associated with orthostatic intolerance. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;40:425–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MPG.0000157914.40088.31

11. Mayer EA, Gebhart GF. Basic and clinical aspects of visceral hyperalgesia. Gastroenterology 1994;107:271–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(94)90086-8

12. Drossman D, Thompson WG, Talley NJ, Funch-Jensen P, Janssens J, Whitehead WE. Identification of sub-groups of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology International 1990;3(4):159–72.

13. Andresen V, Camilleri M, Busciglio IA et al. Effect of 5 days linaclotide on transit and bowel function in females with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;133:761–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.067

14. Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2344–54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0800670

15. Abed H, Ball PA, Wang LX. Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a brief review. J Geriatr Cardiol 2012;9:61–7. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1263.2012.00061

16. Dalrymple J, Bullock IJB. Diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2008;336:556–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39484.712616.AD

17. Hookway C, Buckner S, Crosland P, Longson D. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h701. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h701