Teaching and learning the three-dimensional anatomy of the heart can be challenging. The use of the hand to model structures in the heart has proven useful. In this article a more comprehensive model of the heart using a gloved hand is proposed.

Introduction

The teaching and learning of the three-dimensional (3-D) anatomy of the heart, and especially the coronary arteries and the interpretation of cardiac angiogram radiographs of patients, is challenging to most students.1,2 Studying the anatomy of the heart using specific shapes of the hand during bedside teaching in hospitals and demonstrations of the gross anatomy can be useful.3,4 Harvey appears to have been the first to introduce the concept of using hands to depict the 3-D anatomy of the heart (in the 1950s).5 A 3-D anatomy hand model representing the liver organ has also been developed.4

One hand model,3 which showed the three major arteries of the heart, mimicked the commonly used arteriographic viewing positions by rotation of the hand. A more detailed model,1 which used both left and right hands, demonstrated the 3-D anatomy of the six major arteries of the heart. Duytschaever et al.6 used the left-handed model to demonstrate the structures on the walls of the right atrium. In this report, a more comprehensive hand model of the heart is proposed.

The proposed hand model of the heart

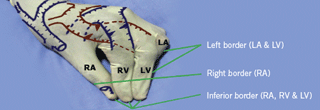

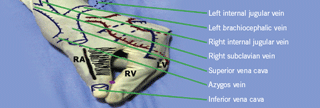

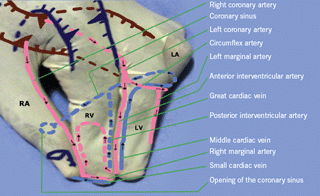

The proposed hand model of the heart illustrates up to 60 features about the heart, (figures 1 and 2). These include the chambers, coronary vessels, venous drainage, valves of the heart and the great vessels of the mediastinum.

In this model, a specific position of the left hand was used. The anterior surface of the heart is ‘constructed’ with the tips of the middle finger and the thumb, grasping the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the index finger tip respectively. The ‘ring’ finger is positioned such that, its proximal interphalangeal joint can be seen, while its distal interphalangeal joint is hidden behind the proximal interphalangeal joint of the middle finger, as shown in figure 1. The fifth digit is completely obscured by the ring finger. The thumb, index finger, middle finger and the last two fingers represent the right atrium, right ventricle, left ventricle and left atrium, respectively. The tips of the thumb, index finger and middle fingers form the inferior or diaphragmatic surface of the heart.

The proximal phalanx of the index finger should be anterior to the proximal phalanx of the middle finger. This will highlight the fact that the superior part of the right ventricle is anterior to the superior part of the left ventricle. This places the aortic valve to the right and posterior of the pulmonary valve, while keeping the inferior part of the left ventricle to the left of the inferior part of the right ventricle.

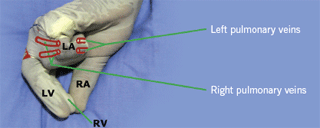

The posterior surface of the heart can be demonstrated in a similar position. The forearm is maximally supinated, until the finger tips of the thumb, index and middle fingers are pointing superiorly, the elbow flexed and the wrist held straight. The metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints of the ‘ring’ finger and last digit need to be strongly flexed, until they are at right angles (figure 2). The ‘ring’ finger and fifth digit represent the left atrium and by strongly flexing them, enables the left atrium to ‘appear’ between the right atrium and left ventricle, while yet in the upper half of the posterior surface of the heart.

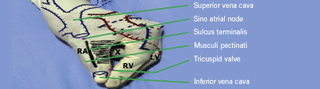

The right atrium is represented by the thumb (figure 3). The following anatomical structures can be labelled: the free wall, terminal crest, auricle, septal surface, tricuspid valve, opening of the coronary sinus, sinoatrial node and the orifices of the caval veins. A small circular piece of paper (about 2 cm2), held between the palmar surface of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb (right atrium) and the postero-lateral surface of the middle phalanx of the ring finger (left atrium) can represent the interatrial septum, on which the fossa ovalis lies.

The triangle of Koch is an area of surgical importance in which the atrioventricular node and its branches are found.6 The triangle of Koch lies between the antero-medial margin of the opening of the coronary sinus, the tendon of Todaro and the septal cusp of the tricuspid valve.6 The fossa ovalis lies just superior to the tendon of Todaro, so the triangle of Koch can be described as lying between the mark for the opening of the coronary sinus, the small circular paper (fossa ovalis) and the mark for the tricuspid valve.

The heart hand model by Duytschaever et al.6 represented most of the structures of the right atrium using the left hand. The proposed hand model has the advantage of showing the other chambers of the heart in relation to the right atrium, albeit on a smaller area of the hand than in the model by Duytschaever et al.6

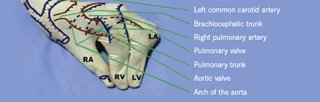

The great arteries and veins of the mediastinum are not represented, but can be drawn on the dorsal surface of the metacarpals, as shown in figures 4 and 5. Several coronary arteries and veins, with their branches and tributaries, can be marked out on the proposed model of the heart as shown in figure 6. The 3-D conceptualisation of flow of blood through the heart can be emphasised by marking the direction of the flow of blood with arrows.

Implications of teaching the three-dimensional perspective

The practical application of this model is best done by students working in pairs. The model created by the hand of one student represents the correct anatomical configuration of the heart in the body of the observer, i.e. the second student, when facing each other. This also encourages students to interact, and to assist the weaker student in consolidating his or her knowledge.

The main strength of this hand model is that it provides a spatial framework for the relations of the anatomic structures of the heart. The left hand preserves the attitudinally correct anatomical configuration of the surfaces and borders of the heart, in relation to the anterior and posterior walls, superior and inferior surfaces and right and left borders. The majority of people are right handed, which enables the student to use the right hand to write on the left hand (with the heart model). However, the right hand can successfully represent the attitudinally correct anatomical configuration of the surfaces and borders of the dextrocordis heart organ.

Limitations

The hand model is meant to provide an approximation of the 3-D layout of the heart, but has some limitations. The upper right border of the right atrium is tilted more towards the right side and the lower right border of the right atrium tilts towards the left. The tilting is caused by poor representation of the transverse cross-section areas of the chambers by the thumb, index and middle fingers. The fingers are leaner than the chambers of the heart and this can be partially solved by separating the finger tips (which represent the inferior surface) by 3 cm from each other. The inferior surface of the heart has a transverse section diameter of 8–9 cm7 and separating the three fingers with 3 cm from each other will approximate the transverse dimension of the normal heart. The most difficult blood vessel to illustrate is the course of the posterior interventricular branch of the right coronary artery (right dominance). The normal course of this artery is to pass through the right anterior atrioventricular groove and then through the posterior interventricular groove. The artery in the hand model passes through the right anterior atrioventricular groove and then crosses the posterior surface of the right ventricle to reach the posterior interventricular groove. Notwithstanding the limitations of the hand model, it provides a readily available 3-D learning aid to the gross anatomy of the heart.

Conclusions

Hand models are virtually free of cost and can be ‘handy’ teaching aids for instructors who have poor quick drawing abilities. The knowledge gained from using the hand model can be easily applied in the clinical setting,3,4 e.g. the clinician can place his or her hand on the chest or upper abdomen of the patient to gain the correct 3-D perspective of the heart. Students may also use their hands during formal anatomy assessments, to represent the heart and to aid their recall of the anatomy of the heart4.

Acknowledgements

This paper was helpfully reviewed by members of the Department of Human Biology of the University of Cape Town, before submission for publication.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Sos TA, Kligfield PD, Sniderman KW. A method for understanding three-dimensional coronary anatomy. JAMA 1980;243:252–4.

- Edvinsson L, Mackenzie E, McCulloch J (eds). Cerebral blood flow and metabolism. New York: Raven Press, 1993;1–683.

- Spring DA, Thomsen JH. A model for teaching coronary artery anatomy. JAMA 1973;225:56.

- Gangata H. A 3-dimensional anatomy model of the liver organ using a gloved hand. Liver International Journal 2008;28:532–3.

- Hurst JW. The approach to the patient. In: Hurst JW, Logue BW. The heart, arteries and veins. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co Inc, 1969;44–47. Quoted in: Spring DA, Thomsen JH. A model for teaching coronary artery anatomy. JAMA 1973;225:56.

- Duytschaever M, Ho SY, Devos D, Tavernier R. The left hand as a model for the right atrium: a simple teaching tool. Europace 2006;8(4):245–50.

- Standring S. Gray’s anatomy. 39th Ed. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2007;995–1027.