Total ischaemic time in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has been shown to be a predictor of mortality. The aim of this study was to assess the total ischaemic time of STEMIs in an Irish primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) centre. A single-centre prospective observational study was conducted of all STEMIs referred for pPCI from October 2017 until January 2019.

There were 213 patients with a mean age 63.9 years (range 29–96 years). The mean ischaemic time was 387 ± 451.7 mins. The mean time before call for help (patient delay) was 207.02 ± 396.8 mins, comprising the majority of total ischaemic time. Following diagnostic electrocardiogram (ECG), 46.5% of patients had ECG-to-wire cross under 90 mins as per guidelines; 73.9% were within 120 mins and 93.4% were within 180 mins. Increasing age correlated with longer patient delay (Pearson’s r=0.2181, p=0.0066). Women exhibited longer ischaemic time compared with men (508.96 vs. 363.33 mins, respectively, p=0.03515), driven by a longer time from first medical contact (FMC) to ECG (104 vs. 34 mins, p=0.0021).

The majority of total ischaemic time is due to patient delay, and this increases as age increases. Women had longer ischaemic time compared with men and longer wait from FMC until diagnostic ECG. This study suggests that improved awareness for patients and healthcare staff will be paramount in reducing ischaemic time.

Introduction

Despite primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) programmes,1-3 ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.2,3 Total ischaemic time predicts mortality in STEMI,4,5 and was adopted by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in the most recent STEMI guidelines.3 This time-period starts at the onset of chest pain and ends at wire cross, including onset-to-door and door-to-balloon time, and outcomes worsen beyond 120 minutes.6 The ESC guideline advises optimal time cut-offs for each step. This document re-highlights ‘time is muscle’, first described by Braunwald 50 years ago: the extent of myocardial injury from coronary occlusion is significantly reversible up to three hours after coronary occlusion.7

Aim

To assess the total ischaemic time of patients presenting with STEMI in an Irish tertiary referral centre and determine factors influencing delays in presentation, treatment, and cardiovascular outcomes.

Method

Ethical approval was granted, and between October 2017 and January 2019 STEMI patients were prospectively enrolled into the study. Patients were included for analysis if they exhibited a culprit lesion that was successfully revascularised. Standard Bayesian statistics were employed to conduct the analysis, which was conducted in SPSS, and a confidence interval (CI) level of 95% was considered significant. Primary outcome was total ischaemic time. Follow-up was conducted during a six-week PCI clinic and 30-day mortality was assessed.

Results

During the study period, 279 patients presented with STEMI. Of these, 262 were deemed suitable candidates for pPCI (i.e. absence of contraindication, such as recent stroke or a late presentation). This included 213 patients who had an occluded coronary artery that was intervened upon, and were recruited to this study. The mean age was 63.9 years (range 29–96 years), with a male to female ratio of 3:1 (men n=163, women n=50).

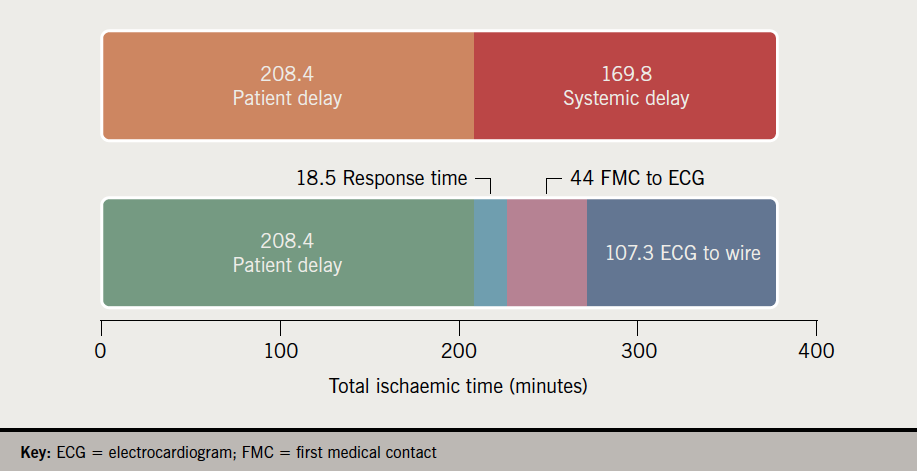

The average individual total ischaemic time across all patients was 387.13 ± 451.70 minutes. The average time from chest pain to ‘call for help’ (i.e. patient delay) was 207.02 ± 396.8 minutes. Relative to systemic delay, patient delay (the time from onset of symptoms to first medical contact [FMC]) represented 54.76% of the total ischaemic time (figure 1A).

Where the patient sought medical attention influenced patient delay. Attendees of their general practitioner (GP) exhibited a higher patient delay compared with other forms of FMC (average 397 minutes vs. 172 minutes, respectively, p=0.0151). Conversely, patients who called for an ambulance called for help earlier compared with other forms of FMC (156.9 minutes vs. 304.5 minutes, respectively, p=0.00398) (figure 1B). The average time from ‘call for help’ to FMC (i.e. response time) was 18.49 ± 30.01 minutes.

The average time from FMC to ECG was 44.9 ± 151.16 minutes, and depended upon type of FMC. The time to ECG was significantly higher in patients who attended their GP/family physician (127 minutes) versus those who were attended by the ambulance service (25 minutes) (p=0.030932). After FMC, 48.7% of patients had an ECG performed in under 10 minutes as per the ESC guidelines. Following diagnostic ECG, 46.5% of patients had ECG to ‘wire-cross’ time within recommended guidelines; 73.9% were within 120 minutes and 93.4% were within 180 minutes.

Women exhibited a significantly longer total ischaemic time than men (508.96 vs. 363.33 minutes, p=0.03515), and this appears to be driven by a significantly longer time from FMC to ECG (104 minutes vs. 34 minutes, p=0.0021). There was no significant difference in the rate of GP attendance in men versus women (p=0.99). Once diagnosis was established there was no difference in ECG-to-wire time between men and women (106.3 minutes vs. 113.47 minutes, respectively, p=0.61708), or patient delay between men and women (254.12 minutes vs. 198.03 minutes, respectively, p=0.44726).

Inpatient death occurred in 5.5% of patients (12/219), of which nine (4.1%) were cardiovascular in origin. There were no additional deaths at 30-day follow-up. Haemodynamic support with intra-aortic balloon pump was required in four cases. Extracorporeal membranous oxygenation support or aortic micro-axial mechanical support was not employed. Death from either cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular causes was not observed to be associated with differences in patient delay, ECG-to-wire time or total ischaemic time in this cohort. There was no difference in mortality among men and women (p=0.4639).

The majority of patients (72.6%) had TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 0 flow on presentation, with lower numbers of other flow grades (TIMI I 4.4%, TIMI II 5.7%, and TIMI III 16.6%). Reduced coronary flow in the culprit vessel on presentation (TIMI 0, I, and II) was associated with higher peak troponin (high-sensitivity troponin I [hs-TnI]) levels compared with patients with normal (TIMI III) flow (6,361 ng/L vs. 5,830 ng/L, respectively, p=0.0001). There was no difference in total ischaemic time between TIMI flow grades. Following intervention, 95.5% of patients exhibited TIMI III flow (1.9% TIMI 0, 1.2% TIMI I and 0.6% TIMI II flow).

Patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI)/coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or PCI (n=12) exhibited no difference in total ischaemic time when compared with patients with no history (n=145) (403.9 minutes vs. 473 minutes, respectively, p=0.9681).

Those presenting to their GP as FMC were significantly less likely to have an ECG in under 10 minutes as per guidelines (relative risk [RR] 2.09, 95%CI 1.49 to 2.92; and number needed to harm [NNH] 2.59, 95%CI 1.68 to 5.69), however, there was no observed difference in ECG-to-wire time once ECG was performed (p=0.86). There was observed correlation between increasing age and total ischaemic time (Pearson’s r=0.1819, p=0.0244), which appears to be driven by patient delay, which exhibited stronger correlation (Pearson’s r=0.2181, p=0.0066). There was no correlation between age and ECG-to-wire time. There were six cases of failure to identify the initial ECG diagnosis (two in a non-PCI hospital emergency department [ED], two as an inpatient in a PCI hospital, one in a PCI hospital ED, and one as an inpatient in a non-PCI hospital).

Discussion

Total ischaemic time is employed by the ESC to assess performance in STEMI. Analysis of the time points that comprise total ischaemic time allow optimisation of the delivery of STEMI services. In this cohort, 54.76% of the total ischaemic time occurred before patients called for help, suggesting a role for awareness programmes. The type of FMC significantly impacted the total ischaemic times seen in patients; those seeing a GP exhibited longer total ischaemic times. The patient delay in this cohort (average 207 minutes) was seen to be higher than in previously reported studies (122 minutes8 and 108 minutes9), but, nevertheless, still comprised a significant proportion of total ischaemic time.

Campaigns have been variably successful in reducing patient delay; showing both success,10-13 and no benefit.14,15 These studies, in conjunction with this study, suggest blanket advice to all patient groups does not guarantee reduced delay times; instead, specific messages may be more effective, i.e. elderly patients are at a higher risk, and attending GP delays diagnosis. The ESC guidelines suggest that patients should call the emergency medical services (EMS) instead of attend their GP. In this cohort, 12% of this patient group attended their GPs, which significantly delayed their diagnosis and treatment. There may be a role for an awareness programme involving GP administrative staff when booking in patients for evaluation of chest pain.

Longer ischaemic time in women was an important finding, and is consistent with data from elsewhere.16,17 This study, however, suggests that a factor for this is a longer time until ECG following FMC. Campaigns for healthcare providers are warranted, highlighting that women may experience atypical symptoms when presenting with STEMI, and ECG should not be delayed if MI is suspected.

The majority of total ischaemic time was composed of patient delay and, thus, further study into the reasons that patients delayed seeking medical assistance would be useful; including factors influencing the decision to call for help (including the psychological factors associated with increased patient delay). These data would be useful in providing messages that overcome barriers to seeking medical care for suspected MI.

Limitations

The data presented are non-randomised and should be interpreted within the limitations of an observational study; such as underestimation of follow-up events/end points. Additionally, patients with no culprit lesion that was amenable to revascularisation (MINOCA) were not included in this study. Also, patients with a small branch culprit or medically managed STEMI that was not intervened upon were not included in the study.

This study was initiated within three months of the introduction of the total ischaemic time metric and so ambulance/GP services may not have been aware that the requirement was to have an ECG performed within 10 minutes.

Conclusion

Increasing age was associated with longer total ischaemic time and patient delay, indicating a need for directed awareness in this demographic. Women waited a significantly longer time for ECG following FMC, which resulted in a significantly higher total ischaemic time; highlighting the need for awareness among healthcare professionals of atypical clinical features associated with STEMI in women.

Patients who attended their GP as FMC experienced a longer wait for ECG and waited longer for an ECG and, once performed, were less likely to be revascularised within 90 minutes.

Key messages

- Total ischaemic time is the recommended metric to measure effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) programmes as per guidelines

- Longer ischaemic times result in worse outcomes. The average total ischaemic time in this cohort was 387 minutes. Patient delay accounted for the majority of this (54.8%)

- Women had a longer total ischaemic time, due to a longer time for electrocardiogram (ECG) following first medical contact (FMC)

- Increasing age was also associated with both longer patient delay and longer total ischaemic time

- Patients who attended their GP as FMC experienced a longer wait for ECG, and once performed, were less likely to be revascularised within 90 minutes

- Future public health messages should clearly state that patients with chest pain should call for an ambulance; not to delay, and not wait to see their GP

- For healthcare workers, it should be highlighted that women are more likely to present with atypical symptoms of acute coronary syndrome and not to delay performing ECG

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

Ethical approval was granted for this study by the University Hospital Limerick medical ethics board.

References

1. Granger CB, Henry TD, Bates WE et al. Development of systems of care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients: the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (ST-elevation myocardial infarction-receiving) hospital perspective. Circulation 2007;116:e55–e59. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.184049

2. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:e362–e425. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6

3. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

4. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP et al. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation 2004;109:1223–5. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000121424.76486.20

5. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Zijlstra F et al. Symptom-onset-to-balloon time and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:991–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00919-7

6. Khowaja S, Ahmed S, Ullah Khan N et al. Acute and stable ischemic heart disease time to think beyond door to balloon time: significance of total ischemic time in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73(suppl 1):227. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(19)30835-6

7. Maroko PR, Kjekshus JK, Sobel BE et al. Factors influencing infarct size following experimental coronary artery occlusions. Circulation 1971;43:67–82. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.43.1.67

8. Song JX, Zhu L, Lee CY et al. Total ischemic time and outcomes for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: does time of admission make a difference? J Geriatr Cardiol 2016;13:658–64. https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.08.003

9. Pereira H, Calé R, Pinto FJ et al. Factors influencing patient delay before primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the Stent for life initiative in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2018;37:409–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2017.07.014

10. Herlitz J, Blohm M, Hartford M et al. Follow-up of a 1-year media campaign on delay times and ambulance use in suspected acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 1991;13:171–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060142

11. Gaspoz JM, Unger PF, Urban P et al. Impact of a public campaign on pre-hospital delay in patients reporting chest pain. Heart 1996;76:150–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.76.2.150

12. Naegeli B, Radovanovic D, Rickli H et al. Impact of a nationwide public campaign on delays and outcome in Swiss patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011;18:297–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741826710389386

13. Bray JE, Stub D, Ngu P et al. Mass media campaigns’ influence on prehospital behavior for acute coronary syndromes: an evaluation of the Australian Heart Foundation’s Warning Signs Campaign. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e001927. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.001927

14. Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Litwin PE et al. Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking medical care: the effect of public education. Ann Emerg Med 1989;18:727–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(89)80004-6

15. Tummala SR, Farshid A. Patients’ understanding of their heart attack and the impact of exposure to a media campaign on pre-hospital time. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2014.07.063

16. Stehli J, Martin C, Brennan A et al. Sex differences persist in time to presentation, revascularization, and mortality in myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012161. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012161

17. Velders MA, Boden H, van Boven AJ et al. Influence of gender on ischemic times and outcomes after ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:312–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.10.007