Remote delivery of cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) has been vital during the COVID pandemic when restrictions have been placed on face-to-face services. In the future, CR services are likely to offer alternatives to centre-based CR, including digital options. However, little is known about the digital access and confidence of CR service users, or their CR delivery preferences.

A telephone survey was conducted of those referred for CR in the London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark (n=60) in which questions were asked about digital access and confidence, as well as current and future delivery preferences for their CR.

Between March and July 2021, 60 service-users met the inclusion criteria and were recruited for a telephone survey (mean age 60 ± 11.2 years). Of those, 82% had regular access to a smartphone, 60% to a computer or laptop and 43% to a tablet device. A high proportion of service users perceived themselves to be ‘extremely’ or ‘somewhat’ confident to use their devices. Thirty-nine (65%) service users would currently prefer a face-to-face assessment, rising to 82% once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions are less. Preferences for accessing exercise were equally split between face-to-face and remotely supported independent exercise, with low interest in digital options. Delivery preferences for education, relaxation and peer support were more heterogeneous with interest in all delivery options.

In conclusion, digital access and confidence in CR service users was good. Redesigning CR services to offer more rehabilitation delivery options, aligned with patient choice may increase uptake and further trials are needed to assess the impact.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant disruption to the delivery of cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) services in the UK, following staff redeployment to acute services and limited access to workspaces.1 With restrictions being placed on face-to-face services due to concerns about safety and disease transmission, many CR services rapidly moved to remote delivery.2 These adjustments led to a significant drop in group-based exercise (–36%) and group-based education (–29%) with a corresponding increase (+16%) in CR staff supported self-managed options.3

In the future, those with cardiovascular disease are likely to be offered alternatives to centre-based CR, including hybrid models that include digital health interventions. Adopting a broader range of evidence-based delivery methods may improve uptake and outcomes of rehabilitation.4

Digital health interventions have been defined as “technology that enables the delivery of care through means such as the use of the internet, wearable devices and mobile apps”.5 A recent literature review reveals that, in CR, the most common modalities used for digital health interventions were smartphones or mobile devices (65%), web-based portals (58%) and email/SMS (35%).5

There is a growing evidence-base for the efficacy of digital CR, with more than 30 unique telehealth trials conducted internationally.6 In the most recent meta-analysis, the use of telehealth for CR was significantly associated with reduced hospitalisations and cardiac events compared with usual care.6

Despite the efficacy of digital CR options being well-established, little is known about the access CR service users have to digital options and their confidence using them. Frederix et al.7 provide a comprehensive overview of the challenges and barriers to large-scale digital health deployment in cardiology in Europe, and comment that typical characteristics associated with lower digital health usage include older age, low health literacy and low socioeconomic and health status. This corresponds with some of the key predictors of digital exclusion identified by the Good Things Foundation Report.8

This survey seeks to better understand the digital access and confidence of those referred for CR in the London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark, and their delivery preferences, both at the time of the survey and once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions are less.

Method

The CR team at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (GSTT) in London, UK, conducted a telephone survey of patients referred for CR between 15 March 2021 and 2 July 2021. Service users met the inclusion criteria if they fulfilled eligibility for CR, according to the recommendations set out in the British Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR) standards and core components,9 and had a general practitioner (GP) within the catchment area of the trust. The GSTT therapies clinical governance, quality assurance and ethical framework approved the project’s method regarding consent, patient confidentiality, anonymity and minimisation of risk of harm to subjects.

A first draft of the survey was piloted with three volunteer CR service users to assess the appropriateness and understanding of survey items, then minor modifications were made in response to their feedback before being used for the study population. Eligible participants were contacted after they had already received an initial telephone contact from the CR team (offering early recovery advice and support). The first consecutive 60 respondents willing to participate in the survey were recruited. Service users were informed their participation and responses would not influence their own future care. Sociodemographic data (age, gender, ethnicity) and clinical details were collected from the referral forms and confirmed on the telephone calls.

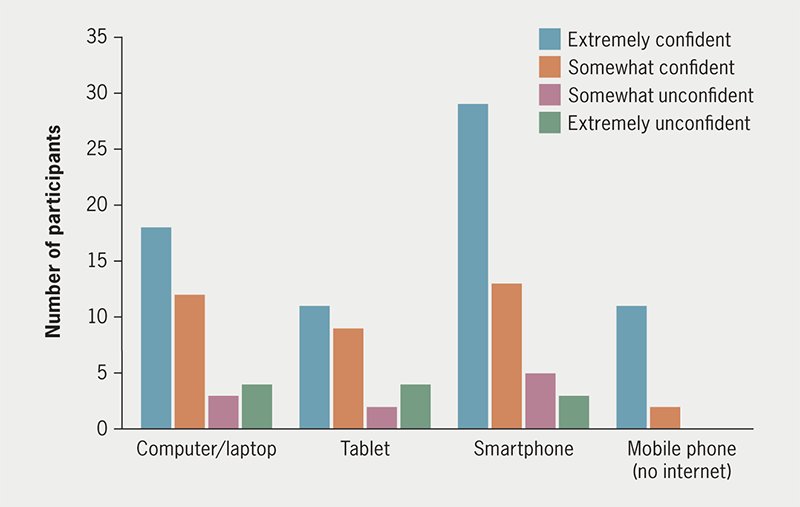

The first question participants were asked was whether they had regular access to any of the following four devices: a mobile phone with no internet, a smartphone or internet-enabled phone, a tablet device and a computer or laptop. They were then asked to rate their confidence using each of the devices they had regular access to using a four-point Likert scale (“extremely confident”, “somewhat confident”, “somewhat unconfident” or “extremely unconfident”).

Participants were given a brief explanation as to what a CR assessment involved, and three delivery options were outlined (face-to-face, a telephone assessment, or a video-call assessment). A description of each option was given (see standardised script in appendix). The extra considerations (social distancing, use of face masks) for a face-to-face appointment were outlined. It was explained that a video call would require access to an internet-enabled device and would be conducted via a secure platform. Participants were asked for their preference for how they would best like to access their CR assessment both at the time of the survey, and once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less, and were asked to give the main reason for their responses.

Appendix. Description of standardised assessment and core component delivery options given to survey participants

|

Assessment Face-to-face: This would involve meeting one of our team at the hospital. Social distancing within the hospital is advised and all staff, patients and visitors are expected to wear a simple face mask, and to sanitise their hands on entering the hospital building. Staff would wear further PPE (gloves, apron and eye protection) when they are required to have closer contact for physical measurements. Any shared equipment is cleaned. Assessment by a video call: This would require an internet-enabled device with a web-cam and would be conducted via a secure platform. No physical measurements of your health or fitness capacity can be taken. Assessment by a telephone call: This would require a telephone. No physical measurements of your health or fitness capacity can be taken. Exercise component Face-to-face small group class: We have reduced class size numbers to a maximum of 8 participants, and redesigned the exercise class format to allow for social distancing. Any shared exercise equipment would be cleaned between use. Social distancing within the hospital is advised and all staff, patients and visitors are expected to wear a simple face mask, and to sanitise their hands on entering the hospital building. Staff would wear further PPE (gloves, apron and eye protection) when they are required to have closer contact for physical measurements. Live virtual small group class: This would be a small group class participating together via a secure platform. This would require an internet-enabled device with a web-cam. You would need to keep your web-cam on and other participants would be able to see you and your background. Pre-recorded exercise session: This would require an internet-enabled device. You would be able to view and follow a pre-recorded exercise session at a time that suits you. Home-based programme support with telephone calls: This would involve you being provided with a home-based programme, e.g., some personalised home-based exercises or a walking programme. This would be supported by some regular phone-calls from a member of our team. Health education component Face-to-face small group session: We have reduced class size numbers to a maximum of 8 participants to allow for social distancing. Social distancing within the hospital is advised and all staff, patients and visitors are expected to wear a simple face mask, and to sanitise their hands on entering the hospital building. Live virtual small group session: This would be a small group class participating together via a secure platform. This would require an internet-enabled device with a web-cam. You would need to keep your web-cam on and other participants would be able to see you and your background. Pre-recorded session: This would require an internet-enabled device. You would be able to view and follow a pre-recorded health education session at a time that suits you. Home-based health education with telephone calls: This would involve you being provided with health information in the form of some written information or a link to a webpage. This would be supported by some regular phone-calls from a member of our team. Relaxation Face-to-face small group session: We have reduced class size numbers to a maximum of 8 participants to allow for social distancing. Social distancing within the hospital is advised and all staff, patients and visitors are expected to wear a simple face mask, and to sanitise their hands on entering the hospital building. Live virtual small group session: This would be a small group class participating together via a secure platform. This would require an internet-enabled device with a web-cam. You would need to keep your web-cam on and other participants would be able to see you and your background. Pre-recorded audio relaxation: You would be sent a link (in a text or email) to an audio relaxation track that you could listen to at a time that suits you. Relaxation information sheet: You would be provided with health information in the form of some written information or a link to a webpage. Peer support Face-to-face small group session: We have reduced class size numbers to a maximum of 8 participants to allow for social distancing. Social distancing within the hospital is advised and all staff, patients and visitors are expected to wear a simple face mask, and to sanitise their hands on entering the hospital building. Live virtual small group session: This would be a small group class participating together via a secure platform. This would require an internet-enabled device with a web-cam. You would need to keep your web-cam on and other participants would be able to see you and your background. A peer support buddy: You would be paired with a volunteer support buddy to make telephone contact with. |

Participants were also asked for their delivery preferences for each component of the CR outpatients programme in turn (exercise, education, relaxation, and peer support) both at the time of the survey, and once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less. Delivery options for each component included small-group face-to-face sessions, taking part from home in live virtual-group sessions, following pre-recorded sessions, being provided with some written information, or a home exercise programme to follow independently with telephone support, or to voice that they were not interested in participating in that component. Once again, participants were asked for the main reason for each of their responses. The data were summarised using descriptive statistics and frequency histograms, and responses to open questions were themed. Binary logistic regressions were used to examine the relationship between participants’ gender, age and ethnicity, and whether the participants had access to an internet-enabled device or not. All assumptions required for the linear-regression analysis were met. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed value of p<0.05.

Results

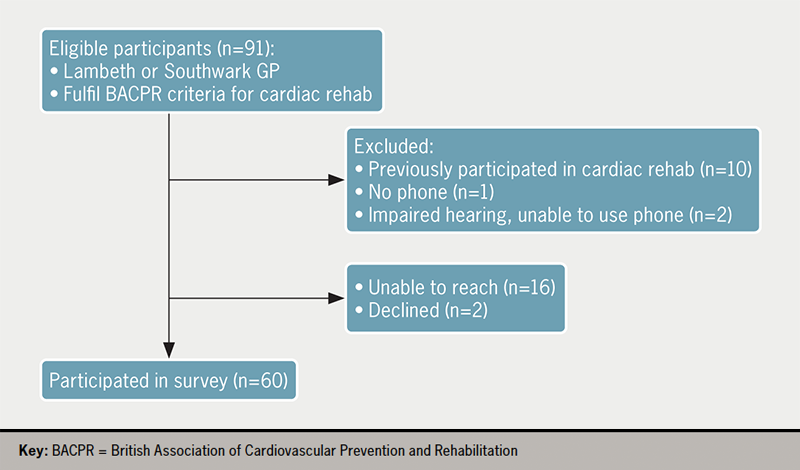

Ninety-one service users were eligible for CR during the study period. Of those, 10 who had previously participated in CR were excluded as it was felt their prior experience of CR would influence their responses. One service user had no phone, two had hearing impairments making use of phone difficult, two declined to take part, and 16 could not be reached despite two calls on separate occasions (figure 1).

Table 1. Reasons for referral and ethnicity

| Reason for referral | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction (MI)/primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | 24 (40) |

| Elective PCI | 11 (18) |

| Heart failure | 10 (17) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery | 6 (10) |

| Heart valve surgery | 5 (8) |

| Angina | 2 (3) |

| MI and CABG | 1 (2) |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity | Number (%) |

| White British | 31 (51) |

| White Irish | 1 (2) |

| Any other white | 7 (11) |

| Indian | 4 (7) |

| Black African | 6 (10) |

| Black Caribbean | 6 (10) |

| Any other black | 1 (2) |

| Any other ethnic group | 3 (5) |

The survey sample (n=60) had a mean age of 60 years (standard deviation [SD] 11.1, range 37–88) and 78% of participants were male. Reasons for referral and ethnicity are shown in table 1. Participant characteristics were similar to those reported in the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation quarterly report on gender and ethnicity for the period of January to June 2021 for the catchment covered by our NHS Trust,10 indicating the survey sample is representative of those who started a core CR programme within this time period.

Digital access and confidence

Most participants had regular access to a smartphone (82%), and/or a computer or laptop (60%), with less having access to a tablet (43%) or mobile phone with no internet (27%). Comparing age, gender and ethnicity, only age was a significant predictor for whether the participants had an internet-enabled device. As age increased, likelihood of having an internet-enabled device decreased (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.089, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01 to 1.174, p=0.017). Neither ethnicity (AOR 0.192, 95%CI 0.73 to 18.24, p=0.14) nor gender (AOR 0.119, 95%CI 0.514 to 12.34, p=0.26) were significant predictors of access to a digital device.

The majority of participants self-reported they were either ‘extremely’ confident or ‘somewhat’ confident using the devices they regularly accessed (figure 2).

Delivery preferences

The delivery preferences for the CR assessment and each component of rehabilitation, both at the time of the survey and when the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less, are detailed in table 2.

Table 2. Delivery preferences of survey participants

| Delivery preferences | At time of survey (n=60) | Once COVID-19 threat and restrictions lessened (n=60) |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | ||

| Face-to-face | 39 (65%) | 48 (82%) |

| Telephone | 16 (27%) | 8 (13%) |

| Video call | 5 (8%) | 4 (7%) |

| Exercise component | ||

| Face-to-face small-group | 25 (42%) | 34 (57%) |

| Live virtual | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| Pre-recorded virtual | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

| Home-based independent | 25 (42%) | 21 (35%) |

| Not interested | 5 (8%) | 4 (7%) |

| Health education | ||

| Face-to-face small-group | 19 (32%) | 24 (40%) |

| Live virtual | 4 (7%) | 4 (7%) |

| Pre-recorded virtual | 6 (10%) | 6 (10%) |

| Information leaflets | 20 (33%) | 15 (25%) |

| Not interested | 11 (18%) | 11 (18%) |

| Relaxation | ||

| Face-to-face small-group | 13 (22%) | 16 (27%) |

| Live virtual | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Pre-recorded audio | 21 (35%) | 19 (32%) |

| Information leaflets | 4 (7%) | 3 (5%) |

| Not interested | 21 (35%) | 21 (35%) |

| Peer support | ||

| Face-to-face small-group | 19 (32%) | 22 (37%) |

| Live virtual | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) |

| Paired with volunteer buddy | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

| Not interested | 36 (60%) | 35 (58%) |

When asked about delivery preferences for their CR assessment, 39 participants (65%) stated they would prefer their assessment face-to-face at the time of their survey, with this rising to 48 participants (82%) once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less. Two themes emerged for preferring face-to-face assessment – the first was that participants wanted the reassurance of a physical assessment, and the second was the enhanced quality of an in-person interaction. Those preferring a remote assessment commonly stated their main reason was the convenience of not having to attend a hospital appointment, and/or that this reduced their risk of COVID-19 exposure and was following the ‘stay at home’ UK Government guidance.

At the time of the survey, equal numbers of participants expressed preference for accessing a face-to-face small-group exercise session (42%) and following a home-exercise programme with telephone support (42%), with lower numbers preferring digital options. Once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less, the number preferring a face-to-face group increased (57%) with preferences for all the other options falling.

The most commonly cited reasons for preferring a face-to-face small-group class at the time of the survey were ‘feeling safer when exercising under supervision’, ‘increased motivation to exercise’ and ‘being with others’. These remained the most cited reasons participants gave for preferring small-group classes once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less. Those who preferred to follow a home-exercise programme with telephone support did so for a number of reasons – themes that emerged included ‘the convenience of being at home’, being able to ‘go at my own pace’ or ‘exercise in my own way’ and ‘the reduced risk of COVID-19’. All these reasons were consistently given across the two time-points, except the ‘reduced risk of COVID-19’, which was understandably cited less often once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less.

Those choosing live virtual exercise as their preferred choice at the time of the survey did so because of the ‘reduced cost compared to a hospital attendance’, ‘feeling safer than a hospital visit’ and ‘being more motivated if exercising with others’. No participants chose live virtual exercise as an option once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less. Those who chose a pre-recorded virtual exercise session did so because of the convenience and reduced risk of COVID-19. Once the perceived COVID-19 restrictions and threat lessened, only one participant chose pre-recorded virtual exercise, the reason cited was for convenience.

The majority of participants were interested in receiving some health education as part of their CR programme. Once again, similar numbers expressing preference for face-to-face group delivery (32%) and written information (33%), with lower interest in digital options. Once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were less, there was a shift towards more participants wanting face-to-face health education delivery (40%). Eleven participants (18%) expressed no interest in health education at the time of the survey, this proportion remained the same once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions lessened.

Reasons most commonly cited for preferring face-to-face group delivery of health education were themed around ‘improved quality of interaction’, which participants felt would be ‘easier to understand’. Many participants also felt they would benefit from questions from their peers and reported higher motivation to attend group health education. These reasons were reported consistently across both time points.

The most cited reason for preferring to receive health information in written form was ‘the convenience/not having to miss work’. Convenience was also cited by those preferring live and pre-recorded digital options, along with ‘preferring a digital format to paper’ and interest in live digital as it is ‘more interactive than pre-recorded’.

Thirty-nine participants (65%) were interested in accessing relaxation in some format as part of their CR programme. The majority (35%) expressed a preference for a pre-recorded relaxation audio track, with some (22%) preferring a face-to-face small-group relaxation session. There was low interest in live digital relaxation or relaxation in a written format. The proportion across the delivery options did not substantially change once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions eased.

The main reasons cited for preferring a pre-recorded relaxation audio track were the ‘convenience’ and the ability to then ‘access it in my own time/whenever I wish’. Those preferring face-to-face group relaxation felt it would be ‘easier to learn in this format’. Those stating no interest in relaxation, either felt no need as ‘stress is not a problem for me’, or already practised a form of relaxation, referencing yoga, meditation, or Tai Chi.

When asked if they would like access to peer support at the time of the study, 60% of participants declined, with this proportion not changing once the perceived COVID-19 restrictions and threat lessened. Themes for declining included ‘already having enough support from family, friends and professionals’ and ‘not being interested in hearing of others’ problems’. Those participants who expressed interest in attending a face-to-face group for peer support spoke of the improved ‘quality of in-person interactions’ and that it ‘might help someone else’. Interest in peer support from a buddy patient by telephone or a live virtual-group peer-support session was low across both time points.

Discussion

This survey provides contemporary data on the digital access and confidence of those referred for CR from our population in the London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark. Overall, access to internet-enabled devices in the surveyed population was good, as was self-reported confidence using these devices. Age was a significant predictor for whether participants had an internet-enabled device, however, as only a small number of the participants did not have an internet-enabled device (n=8), this was an underpowered group and, therefore, difficult to draw firm conclusions from. This finding does, however, agree with previous studies already described.7,11 A survey of 282 individuals eligible for CR in Australia found that age had an important independent association with the use of mobile technology after adjusting for education, employment and confidence. The youngest group (<56 years) was over four times more likely to use any mobile technology than the oldest (>69 years) age group (odds ratio [OR] 4.45, 95%CI 1.46 to 13.55).11

Another recent paper evaluated the digital access and behaviours of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) participants in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. It revealed that, while 48% of participants reported confidence using the internet, 31% of participants had never accessed the internet, and 29% reported no interest in accessing any component of PR via a web-based app. They reported that older age, but not sex, was associated with a lack of internet access (OR 0.94, 95%CI 0.91 to 0.99, p<0.01).12 The authors raised concerns about the readiness of PR users to adopt web-based rehabilitation options.

Despite good digital access and confidence, the majority of those surveyed had a preference for accessing their CR assessment face-to-face, both at the time of the survey and, in increasing numbers, once the perceived COVID-19 threat and restrictions were reduced. So, although it would appear it is feasible to offer digital alternatives to face-to-face CR assessment, retaining choice of mode of assessment appears important in maintaining access.

Delivery preferences of participants for each of the core components of CR were varied. These findings have implications for those redesigning CR services as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. In terms of increasing access and participation in CR, digital and remote options provide a number of opportunities to appeal to groups who might decline participation in conventional face-to-face CR. Those who have difficulty taking time off work, those who experience difficulties or high expense with transport to a CR centre, and those receiving the majority of their care in a separate location to where their CR is offered, may prefer to undertake a digital option rather than decline CR. In line with the recommendations published in previous National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) reports,13 digital CR options can help to provide female-only CR sessions for those preferring this option, which may increase recruitment of more women across all conditions to CR.3 Utility of home-based CR for patients with heart failure14 is currently being developed digitally to offer greater innovation in recruiting heart failure patients to CR. Digital options are encouraged to optimise recruitment and increase uptake,3 but more prospectively conducted research is needed to ensure that this is high quality and effective as a form of CR delivery, and will need strategies to prevent digital exclusion of those without the means or confidence of using these digital technologies.

Epstein et al.15 describe a hybrid model where CR is divided into both face-to-face sessions and virtual, digitally enabled follow-up with home-based remote-monitoring. Redesign of CR pathways in this manner could provide the sought after in-person care and supervision required initially, while leveraging technology at a later stage to enhance care. Providers should use patient preferences to guide which (if any) components of CR should be converted to virtual means in the future. Perhaps the perfect future CR model has elements of both; optimising the areas we can with the best technological solutions, while maintaining our in-person contact, which many service users value highly.

Limitations

This survey had a small sample size, and was a single-centre study, so the results will not represent all those eligible for CR, or be generalisable across the UK. Female gender and non-white/Caucasian ethnicity are under-represented and the sample size may be too small and under-powered to detect differences to achieve statistical significance. A further limitation of this study is that information regarding social deprivation or employment status of participants was not collected, so the influence of these variables could not be analysed. Those surveyed were basing their delivery preferences on a brief description of the options potentially available, and not on any lived experience of them. A follow-up survey of satisfaction following completion of their rehabilitation programme would provide more information of acceptability of delivery modes. The views of subjects suitable for CR but declining to participate after an initial telephone contact from the CR team were not captured in this study. Such individuals may represent the 50% of eligible patients in the UK who do not take up CR and might consider participating if more digital options were available.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this survey indicates digital access and confidence was good in those from Lambeth and Southwark who were referred for CR, which offers an important opportunity to increase access. As COVID-19 restrictions ease, it will be important not to return to conventional centre-based CR delivery only, but to offer genuine choice of mode of delivery to increase access and uptake and reach the ambitious target of 85% set in the NHS long-term plan4.

Key messages

- Digital access and confidence in the survey sample was good

- The majority of participants expressed preference for their cardiac rehabilitation (CR) assessment to be delivered face-to-face. Delivery preferences for the core components were more varied

- Redesigning CR pathways to offer more rehabilitation delivery options, aligned with patient choice may increase national CR access and uptake, and more trials are needed to assess the impact

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

The authors are grateful for a grant from the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Cardiovascular Rehabilitation (ACPICR) project development fund which funded the main author to collect the survey data, and create a short report for dissemination to ACPICR members.

Study approval

The GSTT therapies clinical governance, quality assurance and ethical framework approved the project’s method regarding consent, patient confidentiality, anonymity and minimisation of risk of harm to subjects. No ethical approval was required.

Patient consent

Participants verbally consented to their views being used in the study, knowing their personal information was anonymised.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to the patients who participated in this survey.

References

1. British Heart Foundation. The untold heartbreak. London: BHF, 2021. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-public-affairs/legacy-of-covid

2. O’Doherty AF, Humphreys H, Dawkes S et al. How has technology been used to deliver cardiac rehabilitation during the COVID-19 pandemic? An international cross-sectional survey of healthcare professionals conducted by the BACPR. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046051. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046051

3. National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation quality and outcomes report. London: BHF, 2020. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/national-audit-of-cardiac-rehabilitation-quality-and-outcomes-report-2020

4. Dala HM, Doherty P, McDonagh STJ et al. Virtual and in-person cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2021;373:n1270. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1270

5. Wongvibulsin S, Habeos EE, Huynh PP et al. Digital health interventions for cardiac rehabilitation: systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e18773. https://doi.org/10.2196/18773

6. Jin K, Khonsari S, Gallagher R et al. Telehealth interventions for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019;18:260–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515119826510

7. Frederix I, Caiani EG, Dendale P et al. ESC e-Cardiology Working Group position paper: overcoming challenges in digital health implementation in cardiovascular medicine. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26:1166–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319832394

8. Stone E. Digital exclusion & health inequalities. Sheffield: Good Things Foundation, 2021. Available from: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Good-Things-Foundation-2021-%E2%80%93-Digital-Exclusion-and-Health-Inequalities-Briefing-Paper.pdf

9. British Association of Cardiac Prevention and Rehabilitation. BACPR standards and core components for cardiovascular disease and prevention and rehabilitation. London: BACPR, 2023. Available from: https://www.bacpr.org/resources/publications

10. National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation quarterly report October 2021. York: NACR, 2021. Available from: http://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/quarterly-reports.htm

11. Gallagher R, Roach K, Sadler L et al. Mobile technology use across age groups in patients eligible for cardiac rehabilitation: survey study. J Med Internet Res 2017;5:e161. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8352

12. Polgar O, Aljishi M, Barker RE et al. Digital habits of PR service-users: implications for home-based interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chron Respir Dis 2020;17:1479973120936685. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479973120936685

13. National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. National Audit of Quality and Outcomes quarterly report 2019. London: BHF, 2019. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/national-audit-of-cardiac-rehabilitation-quality-and-outcomes-report-2019

14. Dalal HM, Taylor RS, Jolly K et al.; on behalf of the REACH-HF investigators. The effects and costs of home-based rehabilitation for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the REACH-HF multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26:262–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318806358

15. Epstein E, Patel N, Maysent K, Taub PR. Cardiac rehab in the COVID era and beyond: mHealth and other novel opportunities. Curr Cardiol Rep 2021;23:42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-021-01482-7