Previous studies have shown mixed results comparing short-term mortality in patients undergoing urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation (Urg-TAVI) compared with elective procedures (El-TAVI) for severe aortic stenosis (AS). This study aimed to explore the predictors of requirement for Urg-TAVI versus El-TAVI, as well as compare differences in short- and intermediate-term mortality.

This single-centre, retrospective cohort study investigated 358 patients over three years. Baseline demographic data were collected for patients undergoing elective and urgent procedures, and mortality outcomes at one-month, one-year and three-year follow-up were compared.

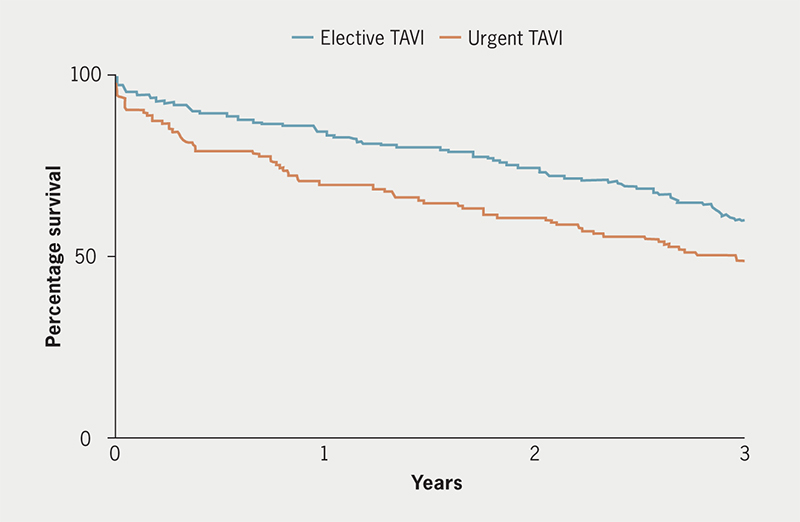

Urg-TAVI was required in 131 (36.6%) patients. Patients undergoing Urg-TAVI were significantly more likely to be female, have poor left ventricular (LV) function, with higher baseline creatinine and higher clinical frailty score (CFS). Higher rates of vascular complications were independently associated with increased mortality at one month. Mortality at one year was associated with higher creatinine level (odds ratio [OR] 1.01, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00 to 1.01, p=0.0013) and an urgent procedure (OR 2.25, 95%CI 1.28 to 3.97, p=0.0048). There remained a higher mortality in the urgent patients at three-year follow-up.

In conclusion, undergoing TAVI urgently did not have a statistically significant effect on 30-day mortality. However, over long-term follow-up of one year, it was associated with worse mortality than elective TAVI, and this persisted out to three years.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is a common valvular pathology that becomes more common with age, with recent studies suggesting a prevalence of approximately 10% in octogenarians.1,2 Current guidelines recommend valvular intervention in severe AS in those patients who are symptomatic.3 Management of AS has been revolutionised by the advent of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), initially for those patients deemed too high risk to undergo a traditional surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).4 More recently, transfemoral TAVI is now the treatment of choice in patients >75 years of age, irrespective of surgical risk, or in younger patients with a higher surgical risk profile.3

Although urgent TAVI is becoming an important treatment for patients admitted to hospital with acute decompensated heart failure secondary to severe AS, the comparison of outcomes between elective and urgent procedures is mixed. There is conflicting evidence published, which has shown that different groups have demonstrated no difference between in-hospital or 30-day mortality5–8 and one-year mortality5 between elective and urgent TAVI procedures, while further groups have demonstrated a significantly increased mortality rate at 30 days and one year in urgent TAVI patients.9–11

We aim to compare outcomes between elective and urgent TAVI at 30 days and one year, as well as at an intermediate length of follow-up of three years, in addition to investigating potential contributing factors that may predict requiring an urgent procedure and subsequent mortality.

Materials and method

Patient selection and demographics

This was a single-centre, retrospective study of 358 consecutive patients with AS undergoing TAVI between 2015 and 2020 at a tertiary cardiology centre. All patients with severe symptomatic AS referred for intervention were assessed by a multi-disciplinary heart team. Patients in whom intervention was appropriate, but SAVR was felt to be unfeasible or high risk due to comorbidity or frailty, underwent TAVI. Collection of baseline demographics (age, sex, extracardiac arteriopathy, history of neurological disease, history of pulmonary disease, poor [<30%] left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF], baseline creatinine level, length of hospital admission post-procedure, concomitant coronary artery disease [CAD], and post-procedural vascular complications), as well as whether the procedure was performed urgently (Urg-TAVI) or as an elective (El-TAVI) procedure, was prospectively collected in a dedicated database. Urg-TAVI was defined as patients admitted to hospital with acute decompensated heart failure or syncope secondary to severe AS considered too unstable to be discharged without a TAVI procedure. Patients considered too unwell for a TAVI procedure that underwent an emergency temporising procedure, such as balloon aortic valvuloplasty, were not included.

Mortality data

Mortality outcomes for each of the 358 patients undergoing TAVI were collected, producing 30-day, one-year, and three-year follow-up mortality, in both the urgent and elective TAVI groups.

Comparison of risk factors for mortality between urgent and elective TAVI

A comparison of the prevalence of demographic and cardiovascular risk factors in patients who had died at 30 days and one year were compared between the patients who died in the El-TAVI group and the patients who died in the Urg-TAVI group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 9, GraphPad (GraphPad Software, San Diego, US). Univariate analysis was performed using unpaired student’s t-test to compare continuous variables (age, creatinine, Katz index of independence in activities of daily living, Canadian Study of Health and Ageing [CSHA] clinical frailty score [CFS], duration of hospital admission) and Chi-squared test was used to compare categoric variables (all other variables). A two-sided p value of <0.05 was deemed significant for all statistical tests. Multi-variate analysis was performed on variables demonstrating statistical significance after univariate analysis using multiple logistic regression. Survival curve differences were calculated using the log-rank approach.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the 358 patients undergoing TAVI in our study population are demonstrated in table 1. Two hundred and twenty-seven (63.4%) patients underwent an El-TAVI procedure, while 131 (36.6%) patients underwent Urg-TAVI. In the study group, 191 patients were male (53.4%) and the average age was 87.0 ± 7.1 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD]).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)

| Variable | El-TAVI N=227 |

Urg-TAVI N=131 |

Univariate | p value |

| Percentage | 63.41 | 36.90 | ||

| Mean age ± SD, years | 87.13 ± 6.94 | 86.90 ± 7.51 | t 0.29 | 0.7725 |

| Male, % | 57.71 | 45.80 | OR 0.62 | 0.0365 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy, % | 22.03 | 22.14 | OR 1.01 | >0.9999 |

| History of neurological disease, % | 14.98 | 8.40 | OR 0.52 | 0.0969 |

| History of pulmonary disease, % | 25.55 | 34.35 | OR 1.53 | 0.0898 |

| Mean Katz index of independence ± SD | 6.01 ± 0.17 | 5.98 ± 0.19 | t 1.29 | 0.1997 |

| LVEF <30%, % | 6.61 | 15.27 | OR 2.55 | 0.0098 |

| Poor mobility, yes % | 47.58 | 46.56 | OR 0.96 | 0.9126 |

| Mean creatinine ± SD, μmol/L | 110.20 ± 62.33 | 130.80 ± 115.50 | t 2.18 | 0.0297 |

| Mean CSHA CFS ± SD | 4.55 ± 1.09 | 4.95 ± 1.03 | t 3.44 | 0.0007 |

| Mean duration of hospital admission post-procedure ± SD, days | 5.98 ± 6.99 | 8.35 ± 12.10 | t 2.30 | 0.0221 |

| Concomitant CAD, % | 35.68 | 40.46 | OR 1.53 | 0.0775 |

| Vascular complications, % | 3.52 | 3.82 | OR 1.09 | 0.8867 |

| Key: CAD = coronary artery disease; CFS = clinical frailty score; CSHA = Canadian Study of Health and Ageing; El-TAVI = elective transcatheter aortic valve implantation; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; OR = odds ratio; SD = standard deviation; Urg-TAVI = urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation | ||||

Procedural success occurred in 354 patients (98.9%). Duration of hospital stay post-procedure is recorded in table 1. We found that duration of time from admission to the procedure being performed urgently was 23 days (median).

Comparison of characteristics between procedural groups

There was a significant difference noted with a higher rate of female patients in the Urg-TAVI group (odds ratio [OR] 1.61, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04 to 2.44, p=0.0365), as well as a higher rate of patients with poor LVEF (<30%) (OR 2.55, 95%CI 1.25 to 5.13, p=0.0098). We also found that there was a significantly higher rate of creatinine in patients undergoing Urg-TAVI compared with El-TAVI (t=2.18, p=0.0297), as well as an increase in the CSHA CFS score (t=3.44, p=0.0007). Of note, these data also demonstrate an increased length of hospital stay post-procedure in the Urg-TAVI group, compared with the El-TAVI group (t= 2.30, p=0.0221) (table 1).

Mortality data

Patients were followed up for three years after the date of procedure. There was a significantly higher rate of death in the Urg-TAVI group compared with the El-TAVI group at the 30-day follow-up period (OR 2.44, 95%CI 1.05 to 5.89, p=0.0439), although this did not meet significance at the point of multi-variate analysis. There was a significantly higher rate of death in the Urg-TAVI group in both the one-year follow-up period (OR 2.33, 95%CI 1.37 to 3.84, p=0.0017), and the three-year follow-up period (OR 1.57, 95%CI 1.01 to 2.44, p=0.0424) (table 2). In-hospital mortality occurred in 13 patients (3.63%).

Table 2. Comparison of mortality between elective and urgent TAVI groups at 30 days, one year and three years

| Variable | El-TAVI | Urg-TAVI | Univariate | p value |

| 30-day mortality, % | 3.96 | 9.16 | OR 2.44 | 0.0439 |

| 1-year mortality, % | 15.42 | 29.78 | OR 2.33 | 0.0017 |

| 3-year mortality, % | 40.09 | 51.15 | OR 1.57 | 0.0424 |

| Key: El-TAVI = elective transcatheter aortic valve implantation; OR = odds ratio; Urg-TAVI = urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation | ||||

The survival curve for the three-year follow-up period is demonstrated in figure 1. Comparison of the rate of death between the Urg-TAVI and El-TAVI group demonstrated a significantly increased risk of death in the Urg-TAVI group over the three-year study period (hazard ratio [HR] 1.49, 95%CI 1.07 to 2.07, p=0.0130).

Comparison of baseline and procedural characteristics in mortality

We found that there was no significant difference between baseline characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors in patients who died in the 30 days after the procedure (table 3) after multi-variate analysis. At the univariate level, we found an increased number of patients undergoing an urgent procedure, as well as those with an increase in the baseline creatinine level, and those with concomitant CAD in the 30-day mortality group, but this did not reach statistical significance after multi-variate analysis. However, we found a significantly increased number of patients with vascular complications in patients who died in the 30 days after procedure after multi-variate analysis.

Table 3. Comparison of procedural and demographic factors for 30-day mortality

| Variable | Univariate | 95%CI | p value | Multi-variate | 95%CI | p value |

| Age | t 0.47 | – | 0.6387 | |||

| Male | OR 1.45 | 0.572 to 3.456 | 0.4181 | |||

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | OR 1.84 | 0.714 to 4.822 | 0.2744 | |||

| Neurological disease | OR 0.33 | 0.031 to 1.954 | 0.4937 | |||

| Pulmonary disease | OR 0.75 | 0.295 to 2.108 | 0.8047 | |||

| Katz index | t 0.00 | – | >0.9999 | |||

| LVEF <30% | OR 0.96 | 0.214 to 3.632 | 0.9611 | |||

| Poor mobility | OR 1.89 | 0.743 to 4.487 | 0.1825 | |||

| Creatinine | t 2.11 | – | 0.0352 | OR 1.00 | 0.994 to 1.001 | 0.0803 |

| CSHA-CFS | t 0.91 | – | 0.3629 | |||

| Duration of hospital admission post-procedure | t 0.37 | – | 0.7101 | |||

| Concomitant CAD | OR 5.28 | 1.969 to 13.52 | 0.0008 | OR 1.22 | 0.468 to 3.099 | 0.6730 |

| Vascular complications | OR 5.45 | 1.490 to 18.97 | 0.0341 | OR 5.59 | 1.123 to 21.33 | 0.0185 |

| Urgent procedure | OR 2.44 | 1.051 to 5.889 | 0.0439 | OR 2.18 | 0.867 to 5.643 | 0.0974 |

| Key: CAD = coronary artery disease; CFS = clinical frailty score; CI = confidence interval; CSHA = Canadian Study of Health and Ageing; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; OR = odds ratio | ||||||

When considering risk factors for one-year mortality, there was a significantly higher creatinine level in patients with one-year mortality, compared with one-year survival (OR 1.01, 95%CI 1.00 to 1.01, p=0.0013) at the level of multi-variate analysis. We also found a significant risk of one-year mortality between the procedure being performed urgently (Urg-TAVI) compared with an elective procedure (OR 2.25, 95%CI 1.28 to 3.97, p=0.0048). There was no significant association between CFS, male gender or poor LVEF and one-year mortality (table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of procedural and demographic factors for one-year mortality

| Variable | Univariate | 95%CI | p value | Multi-variate | 95%CI | p value |

| Age | t 0.20 | – | 0.8366 | |||

| Male | OR 1.81 | 1.07 to 3.07 | 0.0277 | OR 1.61 | 0.90 to 2.92 | 0.1101 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | OR 2.17 | 1.23 to 3.82 | 0.0111 | OR 1.43 | 0.74 to 2.71 | 0.2737 |

| Neurological disease | OR 1.11 | 0.55 to 2.28 | 0.8439 | |||

| Pulmonary disease | OR 0.74 | 0.40 to 1.32 | 0.3885 | |||

| Katz index | t 0.00 | – | >0.9999 | |||

| LVEF <30% | OR 2.54 | 1.25 to 5.38 | 0.0113 | OR 1.32 | 0.54 to 3.04 | 0.5241 |

| Poor mobility | OR 1.01 | 0.60 to 1.70 | >0.9999 | |||

| Creatinine | t 6.05 | – | <0.0001 | OR 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 0.0013 |

| CSHA CFS | t 1.75 | – | 0.0802 | |||

| Duration of hospital admission post-procedure | t 1.02 | – | 0.3103 | |||

| Concomitant CAD | OR 1.18 | 0.70 to 1.99 | 0.5900 | |||

| Vascular complications | OR 1.16 | 0.33 to 4.09 | 0.7362 | |||

| Urgent procedure | OR 2.33 | 1.37 to 3.84 | 0.0012 | OR 2.25 | 1.28 to 3.97 | 0.0048 |

| Key: CAD = coronary artery disease; CFS = clinical frailty score; CI = confidence interval; CSHA = Canadian Study of Health and Ageing; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; OR = odds ratio | ||||||

Discussion

This study has shown a higher mortality rate in patients undergoing Urg-TAVI compared with El-TAVI at 30-day, one-year, and three-year follow-up. We found 4.0% 30-day mortality, and 15.4% one-year mortality in the El-TAVI group, which was in keeping with previous data of elective procedures with 1.3–5.7% for 30-day mortality,6,9,10,12–14 and one-year mortality of 7.8–17.5%.9,10,12,13 Similarly, our findings of 30-day mortality of 9.2% and one-year mortality of 29.8% in the Urg-TAVI group were replicated in previous data of 6.7–17.5% mortality at 30 days,6,9,12–14 and 12.8–29.3% one-year mortality.6,9,10,12,15

In the patients with 30-day mortality, a trend was noted towards higher creatinine levels and a higher number of patients undergoing Urg-TAVI, however, this failed to reach statistical significance following multi-variate analysis. Previous studies are conflicted in regards to 30-day mortality outcomes in patients undergoing elective versus urgent TAVI, with some studies reporting no difference in outcomes,5–8 while others have demonstrated worse 30-day mortality.9–11 We found that vascular complications were significantly associated with 30-day mortality after multi-variate analysis, which is in keeping with previous findings that vascular complications are associated with increased morbidity and morbidity after TAVI.16

Our analysis demonstrated that patients in the Urg-TAVI group were more likely to be female, have poorer LVEF, a higher creatinine level and a higher CSHA-CFS score when compared with those in the El-TAVI group. Our finding that there were a significantly higher number of women in the Urg-TAVI group is in keeping with previous work that has demonstrated a higher prevalence of low-flow gradient AS in women,17 incorrectly underestimating severity of disease, which may lead to late presentation with decompensated heart failure. Furthermore, women in England have lower odds of receiving an aortic valve replacement compared with men,18 and are less likely to be referred for valve replacement than men,19–22 despite similar incidence of disease.

Data from a 2021 review in the Netherlands also showed patients receiving urgent TAVI were more likely to have higher creatinine levels and a poorer LVEF when compared with those receiving TAVI on an elective basis,12 in keeping with our findings. The OCEAN-TAVI registry (Optimized Transcatheter Valvular Intervention-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) review also identified hypoalbuminaemia, peripheral arterial disease and at least moderate mitral regurgitation as predictors of requiring TAVI on an urgent basis.6

In the one-year mortality group, a significantly higher creatinine level was observed when compared with one-year survivors, as well as a higher rate of those undergoing Urg-TAVI. Interestingly, no statistically significant difference was seen in terms of CFS, LVEF or gender. It is well-recognised that patients with worse renal function have poorer outcomes following TAVI and likely represent a more globally unwell population.23,24

There are limited data available with similar comparisons of one-year mortality between El-TAVI and Urg-TAVI patients. Lux et al.12 demonstrated that Urg-TAVI was an independent risk factor for one-year mortality after multi-variate analysis, as was apical access and cerebrovascular complications occurring after the procedure. The OCEAN-TAVI registry6 did not demonstrate increased mortality in the Urg-TAVI group, but cumulative survival rate was significantly lower in the Urg-TAVI patients, therefore, subgroup analysis was performed in the Urg-TAVI group and demonstrated that one-year mortality was significantly associated with prevalence of prior coronary artery bypass graft operation, previous stroke, higher CFS, lower serum haemoglobin and lower serum albumin.

The recent ASTRID-AS (ASessment and TReatment In Decompensated Aortic Stenosis) study25 has demonstrated that a dedicated pathway of treatment of acute decompensated aortic stenosis (ADAS) reduces length of hospital admission, with a trend towards a reduction in a composite outcome of 30-day mortality and acute kidney injury. The scope for shortening time from ADAS diagnosis to procedure is demonstrated by our finding of a long median pre-procedural admission period of 23 days. Further work is required to illustrate statistically significant improved outcome, as well as reduced length of hospital stay.

We have shown that urgent TAVI is an independent risk factor for one-year mortality. The interesting finding of statistical significance after multi-variate analysis suggests that progression of this pathology to this point of its clinical course leads to persistent, pathological changes increasing mortality, which are not wholly reversed by aortic valve implantation by a transcatheter approach.25

These data suggest that patients with severe AS should be monitored for the development of symptoms and completion of surgical valve replacement should subsequently be performed as an elective procedure, prior to the development of decompensated heart failure.

Limitations

This study was conducted at one centre, resulting in small numbers during analysis of some subgroups, and was conducted retrospectively. Nevertheless, appropriate statistical analysis was undertaken including a multi-variate analysis. The total number of patients is relatively small as during the early part of the study a higher proportion of patients underwent SAVR in keeping with local guidelines at the time. This may reduce its generalisability to current high-volume practice. We also note that cause of death was not investigated and, therefore, no comment can be made regarding major adverse cardiovascular outcomes and whether deaths represent cardiac or non-cardiac mortality. Furthermore, given that mortality data were collected from a Welsh clinical database, date of death may have been underestimated in patients who moved outside of Wales, or were non-local residents at the time of procedure.

Conclusion

Undergoing TAVI as an urgent procedure did not have a statistically significant effect on 30-day mortality in multi-variate analysis, mortality at 30 days was 2.5 times higher in the urgent group compared with elective patients. Despite the worse TAVI outcomes in this group, it remains a reasonable therapy option. However, over long-term follow-up of one year, it was associated with worse mortality than elective TAVI and this persisted out to three years. This highlights the importance of early detection of severe AS and performance of TAVI as an elective procedure. In our study population, urgent TAVI was required more frequently in female patients, raising the possibility they have poorer access to timely treatment.

Key messages

- Mortality at one year after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was associated with higher creatinine and urgent procedure

- Mortality over the three-year follow-up period was higher in the urgent TAVI patient group

- Patients undergoing urgent TAVI were more likely to be female, raising the possibility of worse access to timely treatment

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

All patients gave written informed consent prior to their treatment. This study used data collected routinely for national audit and local service evaluation. In view of this, the institute structural research group, utilising the Health Research Authority (HRA) decision tool based on the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research (2017) determined that further NHS ethics approval was not required.

References

1. Danielsen R, Aspelund T, Harris TB, Gudnason V. The prevalence of aortic stenosis in the elderly in Iceland and predictions for the coming decades: the AGES-Reykjavík study. Int J Cardiol 2014;176:916–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.053

2. Eveborn GW, Schirmer H, Heggelund G, Lunde P, Rasmussen K. The evolving epidemiology of valvular aortic stenosis: the Tromsø study. Heart 2013;99:396–400. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302265

3. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2022;43:561–632. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-E-21-00009

4. Iervolino A, Singh SSA, Nappi P, Bellomo F, Nappi F. Percutaneous versus surgical intervention for severe aortic valve stenosis: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int 2021:2021:3973924. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3973924

5. Kabahizi A, Sheikh AS, Williams T et al. Elective versus urgent in-hospital transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2021;98:170–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.29638

6. Enta Y, Miyasaka M, Taguri M et al. Patients’ characteristics and mortality in urgent/emergent/salvage transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insight from the OCEAN-TAVI registry. Open Heart 2020;7:e001467. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2020-001467

7. Landes U, Orvin K, Codner P et al. Urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis and acute heart failure: procedural and 30-day outcomes. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:726–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2015.08.022

8. Ando T, Adegbala O, Villablanca P et al. Incidence, predictors, and in-hospital outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation after nonelective admission in comparison with elective admission: from the nationwide inpatient sample database. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:100–07. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.09.023

9. Kolte D, Khera S, Vemulapalli S et al. Outcomes following urgent/emergent transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the STS/ACC TVT registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11:1175–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.03.002

10. Kitahara H, Kumamaru H, Kohsaka S et al. Clinical outcomes of urgent or emergency transcatheter aortic valve implantation – insights from the nationwide registry of Japan transcatheter valve therapies. Circ J 2024;88:439–47. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-22-0536

11. Wundram S, Seoudy H, Dümmler JC et al. Is the outcome of elective vs non-elective patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation different? Results of a single-centre, observational assessment of outcomes at a large university clinic. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023;23:295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03317-5

12. Lux A, Veenstra LF, Kats S et al. Urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation in an all-comer population: a single-centre experience. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2021;21:550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02347-1

13. Elbaz-Greener G, Yarranton B, Qiu F et al. Association between wait time for transcatheter aortic valve replacement and early postprocedural outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e010407. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.010407

14. Castelo A, Grazina A, Mendonca T et al. Urgent vs non-urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation outcomes. Eur Heart J 2021;42(suppl 1):ehab724.2167. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.2167

15. Abdelaziz M, Khogali S, Cotton JM, Meralgia A, Matuszewski M, Luckraz H. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in decompensated aortic stenosis within the same hospital admission: early clinical experience. Open Heart 2018;5:e000827. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2018-000827

16. Hayashida K, Lefvre T, Chevalier B et al. Transfemoral aortic valve implantation: new criteria to predict vascular complications. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:851–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2011.03.019

17. Iribarren AC, AlBadri A, Wei J et al. Sex differences in aortic stenosis: identification of knowledge gaps for sex-specific personalized medicine. Am Heart J Plus 2022;21:100197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100197

18. Rice CT, Barnett S, O’Connell SP et al. Impact of gender, ethnicity and social deprivation on access to surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis: a retrospective database study in England. Open Heart 2023;10:e002373. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2023-002373

19. Hahn RT, Clavel MA, Mascherbauer J, Mick SL, Asgar AW, Douglas PS. Sex-related factors in valvular heart disease: JACC Focus Seminar 5/7. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:1506–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.081

20. Tribouilloy C, Bohbot Y, Rusinaru D et al. Excess mortality and undertreatment of women with severe aortic stenosis. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.018816

21. Cramariuc D, Rogge BP, Lønnebakken MT et al. Sex differences in cardiovascular outcome during progression of aortic valve stenosis. Heart 2015;101:209–14. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306078

22. Lowenstern A, Sheridan P, Wang TY et al. Sex disparities in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Am Heart J 2021;237:116–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2021.01.021

23. Barbanti M, Gargiulo G, Tamburino C. Renal dysfunction and transcatheter aortic valve implantation outcomes. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016;14:1315–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779072.2016.1234377

24. Mas-Peiro S, Faerber G, Bon D et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease in 29 893 patients undergoing transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement from the German Aortic Valve Registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2021;59:532–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezaa446

25. Patel KP, Mukhopadhyay S, Bedford K et al. Rapid assessment and treatment in decompensated aortic stenosis (ASTRID-AS study): a pilot study. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2023;9:724–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac074