There is much debate about the optimal sedation strategy for transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Despite previous studies demonstrating the potential benefits of combining opiates and benzodiazepines for conscious sedation, and previous published national surveys and recommendations, sedation practice for TEE in clinical practice varies widely within the UK. All UK centres routinely use midazolam, but only 7% of centres use it in combination with an opiate: 14% of hospitals report no routine use of sedation for TEE. There

is no British Society of Echocardiography (BSE) recommended TEE sedation protocol within the UK and even where guidelines exist locally, 82% of operators report being unaware of their details. Consequently, a wide range of sedative doses are used and many patients are reported to be over-sedated. We developed a new protocol for conscious sedation using intravenous pethidine and midazolam for TEE and have shown it to be safe and effective when implemented within an existing TEE service.

Introduction

It is known that there is significant variation in transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) practice, particularly with regards to sedation in the UK.1 Previous studies have demonstrated that choice of sedation used is highly variable and more than half of patients were over-sedated and verbally unresponsive (i.e. under general anaesthesia) during TEE.1 A recent National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) statement in the UK has further highlighted the risks of sedation in the elderly; a population that make up a large proportion of patients undergoing TEE.2 Several speciality-specific guidelines for use of sedation have been published in line with national recommendations,3-8 and a need for TEE-specific guidelines has been recommended. Recent published evidence suggests that a combined sedation strategy incorporating midazolam with an ultra-short acting opiate (remifentanil) significantly improves tolerance of TEE, results in faster recovery time after TEE, and reduces resource consumption.8 However, the use of an infused opiate may be impractical in clinical cardiological practice as it is staff intensive and requires the presence of an anaesthetist. The longer-term safety data for this remifentanil and midazolam combination is also unavailable at present. Prior to developing our new TEE sedation protocol we performed a national survey of TEE sedation practice in the UK and, subsequently, developed a combined intravenous (IV) pethidine and midazolam protocol for routine clinical use. This combination of agents is well established for conscious sedation and has a reasonable safety record internationally. We propose this as a safe and effective TEE sedation protocol and present data from the survey and clinical sedation data on 150 consecutive patients undergoing TEE using this protocol.

Survey of current UK practice

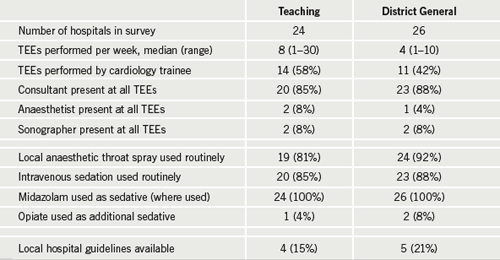

To investigate current UK practice we conducted a survey to establish current national TEE practice in relation to sedation use and awareness of current guidelines (table 1). Fifty teaching and district general hospitals were randomly selected from the Hospital Registry of the United Kingdom.9 The TEE department head was asked to complete a telephone questionnaire: data on the number of TEEs performed per week, use of local anaesthetic and/or sedation and type of sedation were collected, along with details of any local hospital sedation guidelines and who performed TEE routinely. This clarified the ongoing variation in TEE sedation practice in the UK.

A combined IV sedation protocol – a case series

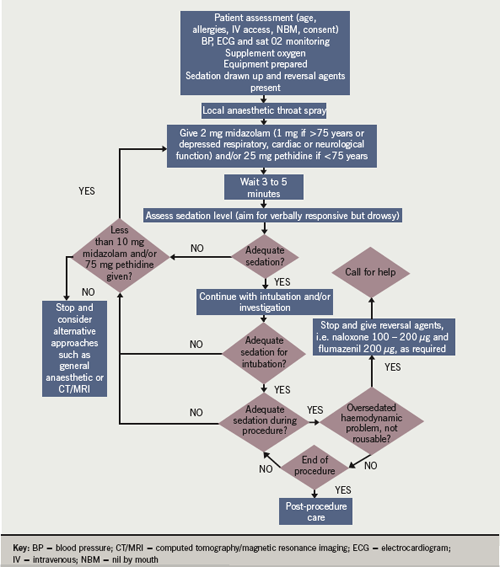

Following collation of this national survey, we designed a local protocol using IV pethidine as the opiate of choice. This protocol took into account the length and level of sedation required for TEE, and principles from the local endoscopic and published national guidelines for safe sedation.3-6 The full protocol is presented in figure 1.

We then evaluated this new combined opiate and benzodiazepine TEE-specific protocol to assess whether it can be introduced safely and effectively into an existing TEE service. An independent medical practitioner, who was unaware of the change in practice, collected and analysed data on sedation use, procedural details (use of monitoring, oxygen, ease of intubation), adverse events and patient experience. Data on the final 100 patients included a further quantitative assessment of sedation using the Ramsay sedation level10 to allow a more accurate assessment of appropriate sedation.

Results

A total of 151 patients (80 male and 71 female) underwent TEE using the new sedation protocol. All had electrocardiogram (ECG), blood pressure and oxygen saturation monitoring (Sat02) throughout the procedure. All patients received 4 L/min of supplemental oxygen via nasal cannulae, lidocaine throat spray (3–4 puffs of 4% lidocaine) and an initial dose of midazolam. The dose of midazolam was titrated to effect with a usual starting dose of 2 mg, unless the patient was over 75 years old, in which case 1 mg was initially administered intravenously. The median total dose administered for this cohort was 2 mg (range 1–8 mg). One hundred and twenty-eight patients (84%) received pethidine in addition to midazolam. Of these, 119/128 (93%) patients received 25 mg and 9/128 (7%) patients received 50 mg pethidine. For the final 100 patients, 72 had Ramsey sedation stage 2–3 prior to intubation and 90 patients were at this stage at the end of the procedure. There was a significant drop in blood pressure between the start and end of the procedure from 130/70 mmHg to 117/66 mmHg (p=0.04), but adverse event monitoring demonstrated no periods of hypoxia or bradycardia for the entire cohort. Six patients (4%) required IV fluids due to clinically significant hypotension (systolic <100 mmHg) and 2/151 patients (2%) received sedation reversal using flumazenil.

Discussion

It is known that there is considerable variation in TEE practice in different countries.11 In a multi-centre survey of TEE safety, only one of 15 centres used routine sedation.11 Factors such as patient comfort and operator preference may have increased the use of conscious sedation in recent years, but it remains far from ubiquitous. Current safe-sedation guidelines support the use of routine conscious sedation for TEE, but draw attention to the dangers of unregulated, operator-dependent practice,6 in particular, adverse events such as over-sedation and cardio-respiratory depression.12,13 To this end, guidelines stress that sedation must be carefully titrated to patient requirement and verbal contact must be maintained at all times. Clinicians should be aware that if verbal contact is lost then the patient is under general anaesthesia and the medical practitioner requires appropriate competence and training to manage this scenario, including a clear understanding of who and when to call for help.

Our sedation guidelines adopt these principles with increased pharmacological titration according to patient sedation level (based on a target of grade 3 on the Ramsey sedation scale9). In view of recent statements regarding risks of sedation in elderly patients, a reduced starting dose of 1 mg midazolam is advised in those over 75 years. These benzodiazepine doses have no analgesic effects and additional opiate analgesics were, therefore, incorporated. Opiates also have sedative properties and are respiratory depressants, which has led to safety concerns when aiming for controlled conscious sedation.14 Our results suggest that pethidine can safely be used alongside midazolam within a monitored environment. However, it can also be seen from our results that two patients required flumazenil for over-sedation, and it is noteworthy to highlight that the NPSA now suggest that flumazenil use is a reliable quality indicator for sedation technique.

We have not compared alternative sedation strategies, such as the use of fentanyl, and controlled trials may be of value to establish the most appropriate regimen. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that the use of combined pethidine and midazolam conscious sedation during TEE is safe and practicable in clinical practice within the UK. It should be noted that pethidine has a half-life of several hours, making it less forgiving of bad sedation practice, but, fundamentally, the most important aspect of any sedation protocol is that clinicians are familiar with the doses and pharmacokinetics of the agents they are using. We believe that, if used appropriately, it is a safe and reliable agent for TEE. Finally, we acknowledge that there are some patients with such severe co-morbidities (including heart disease) that they are unable to tolerate safe sedation for TEE. In these situations, TEE without sedation may be considered if deemed essential, or suboptimal evidence from transthoracic or other imaging may be all that is available, and that has to be accepted. The striking lack of awareness of sedation guidelines highlighted as a problem in 20001 appears to still be prevalent, and we recommend a national agreed strategy for TEE sedation that incorporates both an opiate and benzodiazepine.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Editors’ note

An editorial related to this article by Terry McCormack can be found on page 103 of this issue.

Key messages

- Sedation practice for transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in clinical practice varies widely throughout the UK

- While a benzodiazepine is commonly used for sedation, they are not often combined with an opiate

- A protocol for conscious sedation using midazolam and pethidine was developed and successfully implemented in an existing TEE service

- We recommend a national agreed strategy for TEE sedation that incorporates both an opiate and benzodiazepine

References

1. Sutaria N, Northridge D, Denvir M. A survey of sedation and monitoring practices during transoesophageal echocardiography in the UK: are recommended guidelines being followed? Heart 2000;84(suppl II):ii19.

2. National Patient Safety Agency. Reducing risk of overdose with midazolam injection in adults. Rapid response report NPSA/2008/RRR0111. London: NPSA, 9 Dec 2009.

3. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Fetal awareness: report of a working party. London: RCOG, 1997.

4. British Thoracic Society. Guidelines on diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy. Thorax 2001;56(suppl 1):11–21.

5. Royal College of Anaesthetists and Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Guidelines for local anaesthesia for intraocular surgery. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2001.

6. Working Party report. Guidelines for sedation by non-anaesthetists. London: Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1993.

7. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD). Elderly patients vulnerable because of excessive doses of sedatives. London: NCEPOD, 2007.

8. Renna M, Chung R, Li W et al. Remifentanyl plus low-dose midazolam for outpatient sedation in transesophageal echocardiography. Int J Cardiol 2009;136:325–9.

9. Dr Foster Research Limited. Full list of NHS & private hospitals in the UK. Available from: http://www.drfosterhealth.co.uk/hospital-guide/full-hospital-list/ [accessed 10 Feb 2007].

10. Ramsay M, Savege T, Simpson B et al. Controlled sedation with alpaxalone-alphadolone. BMJ 1974;2:656–9.

11. Daniel W, Erbel R, Kasper W et al. Safety of transoesophageal echocardiography. A multicentre survey of 10419 examinations. Circulation 1991;83:817–21.

12. Lazzaroni M, Bianchi-Porrow G. Premedication, preparation and surveillance. Endoscopy 1999;31:2–8.

13. Bubiens RS, Fisher JD, Gentzel JA et al. NASPE expert consensus document: use of i.v. (conscious) sedation/analgesia by nonanesthesia personnel in patients undergoing arrhythmia specific diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical procedures. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998;21:375–85.

14. Hanley JA, Lippman-Hand A. If nothing goes wrong, is everything alright? JAMA 1983;259:1743–5.