The 2010 Scientific Meeting of the Scottish Heart and Arterial Prevention Group (SHARP) took place in November 2010 and addressed, in detail, the interface of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with other disease categories and specialties.

Opening the meeting, held in Dunkeld, Perthshire, SHARP trustee Professor Stuart Pringle (Professor of Cardiology, University of Dundee) set the current scene by explaining that very few patients seen in hospital today are uncomplicated and straightforward, mainly as a result of their multiple co-morbidities. This has a profound effect on how they are managed, the drugs that are used and any potential drug interactions.

Diabetes

The association between diabetes and all aspects of CVD has been a major topic at previous SHARP meetings. Dr Alan Rees (Chairman of HEART UK and a diabetes specialist in Cardiff) warned delegates not to view diabetes in a too ‘glucocentric’ way, pointing out that in type 2 diabetes the effect and condition have been present for up to seven years at diagnosis. Evidence was highlighted showing that patients without diabetes presenting with a myocardial infarction have a high prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism. Early identification of these patients when they are admitted may help in the assessment of those within the cohort who may be at an increased overall ongoing risk.1

Respiratory disease

The association between respiratory disease such as chronic obstructive airways disease (COAD) and CVD was explained by two Tayside respiratory physicians, Drs Stuart Schembri (Perth) and John Winter (Dundee). It is apparent that the association between COAD and CVD may extend beyond common risk factors such as increasing age, smoking, hypertension, obesity and dyslipidaemia.2 Reduced FEV1 has long been recognised as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. It was proposed that peripheral lung inflammation may cause a ‘spillover’ of cytokines, such as interleukin and tumour necrosis factor, into the systemic circulation which may increase acute-phase proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP). Systemic inflammation may then initiate or worsen co-morbid conditions.3 Arterial stiffness is increased in patients with COAD predisposing them to systemic hypertension, which is 1.6 times higher in these patients and perhaps related to an impairment of endothelial function.

Drugs and respiratory disease

There is often a reluctance to use beta blockers, which are widely used in patients with CVD, in patients with co-existent COAD although the evidence presented suggests that beta blockers will reduce the risk of exacerbations and improve mortality survival rates.4 Observational studies have suggested that inhaled corticosteroid used in patients with COAD may potentially confer cardiovascular or mortality benefit but clinical trials have yet to demonstrate significant benefit on myocardial infarction risk or reduction of cardiovascular death.5 Also presented was data from the TORCH (Towards a Revolution in COAD Health) study on the long-term risk of long-acting beta2 agonists and inhaled corticosteroids either alone or in combination. A post-hoc analysis of the data did not suggest in this particular trial an increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients with moderate to severe COAD treated with these drugs.6 Concern remains that inhaled anti-cholinergic drugs may also be implicated in increasing the risk of cardiovascular complications.

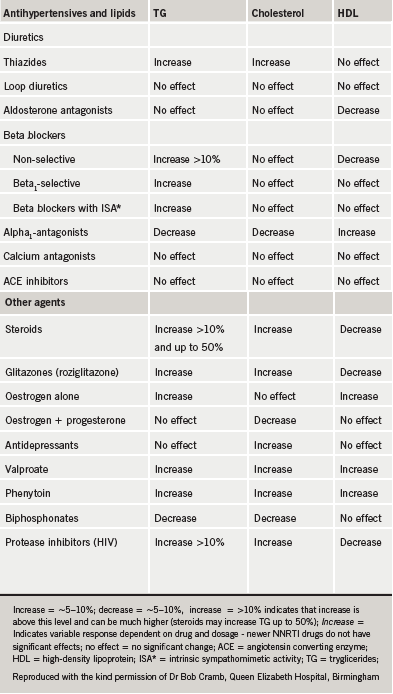

Drugs and lipid measurement

Measurement of serum cholesterol and other lipid parameters is one of the most commonly used tests in monitoring patients with long-term conditions where polypharmacy is rarely absent. Dr Bob Cramb (Chemical Pathologist, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham) led a workshop on the drugs that may affect lipid measurement. Table 1 summarises drugs that produce a 5-10% increase or decrease in measured values, although caution is required on the long-term implication of these changes in lipid levels. They may be more relevant in primary prevention risk scoring where using measured levels to score CVD risk, which is altered by concomitant drug use, may lead to over treatment or underestimation of risk.

Uric acid

The potential use of uric acid as a risk marker for CVD was discussed in a workshop facilitated by Dr Helen Harris (Consultant Rheumatologist, University of St Andrews). The association between raised urate, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, diabetes and renal disease has previously been noted, and there may be a future increased use of allopurinol as an effective drug to reduce raised blood pressure.7 Data from APEX (Febuxostat, Allopurinol and Placebo-Controlled Study in Gout Subjects) and FACT (Febuxostat versus Allopurinol Control Trial in Subjects with Gout) on the possible benefits of febuxostat, a non-purine selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, when compared with allopurinol in lowering serum uric acid was also highlighted and discussed.8

Rheumatoid arthritis

In the afternoon plenary session, Dr Harris discussed the increased cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) which may be equivalent to that found in those with diabetes. Similarly to COAD, the excess risk is not explained by traditional risk factors and inflammation seems likely, once again, to play a large part in the pathogenesis.

The 10 recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in rheumatoid arthritis from the European League against Rheumatism were highlighted, especially the need to multiply traditional risk models calculations by a factor of 1.5, and to ensure adequate control of active disease in those with RA which will help to lower their CV risk.9 Speaking from the floor, SHARP trustee Dr Bill Simpson (Chemical Pathologist, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary) pointed out that inflammation in these patients will drive down cholesterol levels, perhaps making their absolute cholesterol levels less relevant. Dr Tom McDonald (Professor of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Dundee, and SHARP trustee) pointed out that there is some evidence that the effects of cholesterol reduction using statins in RA may be less beneficial. The TRACE RA trial which allows the statin dose of atorvastatin to go up to 80 mg may compensate for any discrepancy and give a definitive answer on the benefits of CVD risk reduction in those with RA.10

Atrial fibrillation

The ATHENA trial11 on the benefits of dronedarone was highlighted by Dr Neil Grubb (Consultant Cardiologist, Royal Infirmary Edinburgh) in his talk on advances in the management of arrhythmias, and also in the debate as to whether atrial fibrillation should be managed by gadgets (Dr Paul Broadhurst, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary) or drugs (Dr Riyaz Kaba, St Georges and Chertsey Hospitals, London).

In the trial, the main outcome was first hospitalisation due to cardiovascular events or death. The hazard ratio benefit for dronedarone versus placebo was 0.76 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.84 p<0.001). The significant side effects seen in the treatment group were bradycardia, QT-prolongation, diarrhoea, nausea, rash and an increase in serum creatinine.

Looking after the young

Dr Peter Bloomfield (University of Edinburgh) in a session on cardiac problems in the young was able to highlight from his experience how well Scottish children with congenital heart disease are managed and followed up throughout their life – a significant Scottish success story at a difficult time for the NHS nationally within the UK.

Diary date

The next SHARP national meeting will be held at Dunkeld House Hotel, Perthshire, on 24th and 25th November 2011. Other regional educational events are planned for 2011.

References

1. Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G et al. Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:2140-4.

2. Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD . Eur Respir J 2008;32:962-9 (Epub 2008 Jun 25).

3. Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1165-85.

4. Rutten FH, Zuithoff NP, Hak E, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Beta-blockers may reduce mortality and risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:880-7.

5. Singh S, Loke YK. An overview of the benefits and drawbacks of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010; 5:189-95.

6. Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B et al., TORCH Investigators.Cardiovascular events in patients with COPD: TORCH study results. Thorax 2010;65:719-25.

7. Grayson PC, Kim SY, Lavalley M, Choi HK. Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 63:102-10 (doi: 10.1002/acr.20344).

8. Febuxostat for the management of hyperuricaemia in people with gout. NICE Technology appraisal TA164 http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA164 (accessed January 2011)

9. Peters M JL, Symmons D PM, McCarey D et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 325-31.

10. TRACE RA: Trial of Atorvastatin for the primary prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Rheumatoid Arthritis. http://www.dgoh.nhs.uk/tracera (accessed January 2011)

11. Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van Eickels M et al, ATHENA investigators. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;360:668-78.