As the proportion of patients above the age of 80 years in the UK is increasing it is likely that in the future cardiac centres will be treating an increasing number of octogenarians as part of their patient population. Despite this, there are little contemporary outcome data in this group of patients who often have complex coronary disease.

We aimed to assess, first, the change in demographics of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) over a 9-year period at a tertiary cardiac centre within the UK and, second, whether there has been a change in outcome for these patients in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE). A retrospective review of registry data on patients who underwent PCI at our institute from 2000–2008 was undertaken. Patients were divided into three groups according to when they underwent PCI: Group A 2000–2002, Group B 2003–2005 and Group C 2006–2008. Demographic data were collected along with the nature of coronary disease treated and MACCE rates.

There were 3,108 patients in Group A, 4,744 patients in Group B and 3,860 patients in Group C. The use of rotablation increased from Group A (0.4%) to Group C (3.8%) (p<0.01), over-the-wire balloons from Group B (0.8%) to Group C (2.7%) (p<0.01), and microcatheters from Group B (0.1%) to Group C (1.25%) (p<0.01). This was accompanied by a decline in total MACCE rates from Group A (1%) to Group C (0.43%). The proportion of patients >80 years increased from Group A (5.8%) to Group C (12.2%) (p<0.01), and a similar decline in MACCE rates was also observed in this age group from Group A (4%) to group C (0.9%) (p<0.01).

In conclusion, the proportion of elderly patients requiring PCI is increasing. In this group of patients, PCI appears safe and is associated with declining complication rates.

In 2008 there were 1.3 million members of the population of the UK above the age of 85 years.1 By 2033 this number is expected to more than double to 3.2 million.1 This would represent approximately 5% of the population. Given the marked prevalence of coronary disease in the elderly it is likely that in the future cardiologists will be treating an increasing number of octogenarians as part of their patient population.

Despite this, there remains a reluctance to perform percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in this patient group. Cardiologists often opt for medical treatment, and perceive this to be an acceptable strategy given the co-morbidities that octogenarians often have. Registry data, nevertheless, demonstrate that PCI in octogenarians can be performed with an acceptable risk. Angiographic success has been reported to be high with an estimated in-hospital mortality of 3.7%.2,3 This risk being particularly related to recent myocardial infarction (MI) with mortality rates of 1.35% with no history of recent MI and 13.8% in those patients with a recent event (<6 hours).3

The question remains as to whether PCI in this patient group confers a long-term benefit compared with medical therapy alone. Studies suggest that, not only is a survival benefit achieved by PCI when compared with medical therapy alone, but that this is more pronounced than in younger patients.4 Perhaps more importantly, PCI also appears to improve the quality of life for those patients above the age of 80 years.5

There are little current data that has assessed the changing practice of PCI in octogenarians in a modern patient cohort and whether with emerging technologies survival has improved in recent times. The aim of the current study was, therefore, to first assess the change in demographics of patients undergoing PCI in the last 10 years, and then to assess whether there has been a change in outcome for octogenarians undergoing PCI in this same time period.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients undergoing PCI at the Royal Sussex County Hospital between 2000 and 2008. Data were collected on patient demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, indications for intervention, coronary lesion characteristics and procedural complications. To assess for changes in trends over the study period, the patient cohort was divided into three groups. Patients undergoing PCI in the years 2000–2002 (Group A), 2003–2005 (Group B) and 2006–2008 (Group C).

Population

The Sussex Cardiac Network consists of a single PCI centre with four PCI operators, within a cardiothoracic surgical facility and three further non-surgical PCI centres with a further seven PCI operators. It serves a population in the region of 1.4 million, of whom 22% are retired and 8.6% are above the age of 75 years.

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables or median (interquartile range) for skewed data. Differences between patient groups were analysed with the two-sample t test for continuous variables and the Χ2 test for categorical variables. Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics

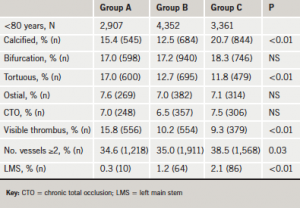

During the total study period there were 11,712 patients who underwent PCI at our institute. There were 3,108 patients in Group A, 4,744 patients in Group B and 3,860 patients in Group C. The proportion of patients ≥80 years who underwent PCI increased over the study period. There were 180 (5.8%) patients in Group A, 358 (7.5%) in Group B and 471 (12.2%) in Group C who were ≥80 years of age (p<0.01) (figure 1). Similarly, the proportion of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) ≥80 years also increased (58 [3.8%] patients in Group A, 83 [5.4%] patients in Group B and 107 [7.6%] patients in group C [p<0.01]).

Coronary intervention

There was a tendency to treat more complex lesions over time. The proportion of calcified and tortuous lesions increased, as did the frequency of multi-vessel and left main stem (LMS) PCI. This was accompanied by an increased use of rotablation from Group A (0.4%) to Group C (3.8%) (p<0.01), over-the-wire balloons from Group B (0.8%) to Group C (2.7%) (p<0.01) and microcatheters (catheters designed for highly stenosed complex lesions through tortuous vessels) from Group B (0.1%) to Group C (1.3%) (p<0.01).

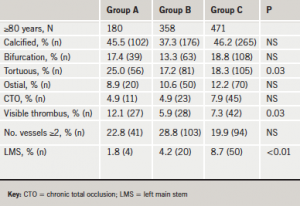

Tables 1a and 1b give the nature of coronary disease treated according to age category. There was an increase in the proportion of calcified, tortuous and LMS disease treated in the octogenarians compared with patients <80 years old. This was accompanied by a proportional rise in the use of rotablation from two (1.1%) patients in Group A to 12 (3.4%) patients in Group B and 46 (9.8%) patients in Group C (p<0.01) in octogenarians.

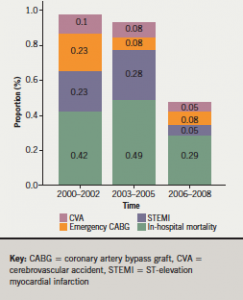

Total outcome

Despite the increasing complexity of lesions treated, there was a decline in MACCE rates from Group A to Group C (figure 2). The total MACCE rate in Group A was 1%, in Group B 0.93% and in Group C 0.43%. In particular, there was a decline in the proportion of patients experiencing ST segment elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) and those requiring emergency coronary bypass surgery.

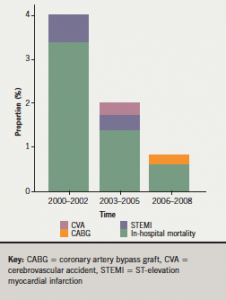

Outcome: octogenarian subgroup comparison

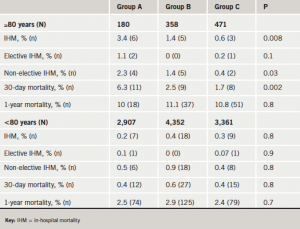

Figure 3 gives the comparison of MACCE between elective cases, urgent cases and patients <80 and ≥80 years of age. The MACCE rate of those patients >80 years of age was far greater than those patients in the other groups (4% vs. <1% in Group A). This, however, declined markedly over the study duration to 0.9% in the Group C study period (p<0.01). A subgroup analysis of this group demonstrated that the major factors responsible were a decline in in-hospital mortality from Groups A to C (3.4% to 0.6%) (p=0.008) in those patients undergoing urgent PCI, and the rates of STEMI post-PCI (figure 4). The improvement in mortality rates was maintained to 30 days but not to one year (table 2). A similar decline was not noted in those patients <80 years, where the low rates of mortality were noted throughout the study period.

Discussion

The main finding of the current study is that, although the number of octogenarians undergoing PCI has increased over the last eight years, the complexity of coronary disease treated by PCI is increasing and MACCE rates are on the decline.

As life expectancy improves, the proportion of patients above the age of 80 years is increasing. Indeed patients aged >85 years are currently the largest growing population group in the UK. It is well recognised that cardiovascular and coronary heart disease risk increases with age and that mortality is greatest in the very elderly. It is currently estimated that the rate of acute coronary syndrome in patients above the age of 85 years is in excess of 45 people per 1,000.6

Despite this, a proportion of cardiologists remain reluctant to perform PCI in octogenarians owing to perceived patient frailty and concurrent co-morbidities. In these patients pharmacological therapy is often the preferred treatment strategy. Given the predicted demographic changes in population characteristics it is likely that this strategy will have to evolve in order to treat a cohort of patients who may arguably benefit the most from intervention in terms of quality of life.5

Our data reflect a trend to offer more invasive therapy to these patients. Over the last decade we have seen increasing evidence supporting the use of PCI in the elderly. This has been, not only for patients with chronic stable angina,5,7 but also for patients with acute coronary syndromes. In this group, revascularisation has been shown to be successful and also to confer a survival benefit over pharmacological therapy, particularly when compared with patients <80 years of age.8,9 Nevertheless, elderly patients suffer from more significant co-morbidities than their younger counterparts. There is an increased incidence of chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus and also impaired left ventricular systolic function.2 This inevitably impacts on the nature of coronary disease with patients having more complex coronary disease, often with calcified lesions and multi-vessel involvement.10 This renders them an inherently higher-risk group in whom to perform PCI.11 Higher rates of complications, such as acute renal failure, vascular complications, haemorrhage and overall MACCE,4 have been observed. Hospital mortality has been estimated to be 3.4%, with a risk of stroke approaching 0.7%.2,3

The results from the current study not only confirm the safety of PCI in 1,002 patients aged above 80 years, but also that the rates of mortality and stroke from PCI have declined significantly over the last nine years to currently predicted rates of 0.6% and 0%, respectively, in our patient cohort. In particular, we observed improved outcomes in patients undergoing urgent PCI for acute coronary syndrome, where the current in-hospital mortality rate was only 0.4%.

Interestingly, the decline in MACCE rates was most pronounced in elderly patients with only minor improvements noted in those patients <80 years (in-hospital mortality 0.3%). This occurred despite increasingly complex PCI cases where rotablation was employed more frequently for calcified coronary vessels, microcatheters were used to aid in crossing difficult lesions and LMS lesions were treated with less reserve. Although it remains speculative as to why results improved, given the treatment of more complex coronary lesions, it is likely that this was related to:

- increasing availability of modern inflation balloons

- advancements in stent design

- more modern pharmacological therapies

- operator experience.

The change in the nature of coronary disease observed is not felt to reflect a change in either the incidence or prevalence of severe coronary disease. It more accurately reflects a change in practice and nature of work that our institute received over the study duration. Increasingly, routine PCI work was conducted at adjacent hospitals where catheterisation facilities were available. This left more acute and unstable cases, patients with multi-vessel disease and patients with complicated lesions to be dealt with at our centre. It is possible that this factor may have accounted for a decline in MACCE rates as operators gained further experience in coronary disease of this nature.

The decline in hospital mortality rates was maintained to 30 days following PCI in our patients aged greater than 80 years. We did not observe a similar improvement in one-year mortality rates. This remained high at 10–11% from Group A to C. This potentially suggests that PCI in this patient group does not confer a significant mid-term survival benefit. Nevertheless, we did not collect data on quality-of-life measures and symptom-improvement parameters pre- and post-PCI. The authors recognise that these factors are perhaps more relevant outcome measures in this patient population where the natural history of concurrent co-morbidities need to be accounted for.

Acknowledgement

Dr Ronak Rajani is currently funded by the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- The proportion of elderly patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is increasing

- In this group of patients, PCI appears safe and is associated with declining complication rates

References

1. Office of National Statistics. National population projections. Fareham, Hampshire, UK: Office of National Statistics, 2009.

2. Weintraub WS, Veledar E, Thompson T et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in octogenarians during the stent era (National Cardiovascular Network). Am J Cardiol 2001;88:1407–10, A6.

3. Klein LW, Block P, Brindis RG et al. Percutaneous coronary interventions in octogenarians in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry: development of a nomogram predictive of in-hospital mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:394–402.

4. Graham MM, Ghali WA, Faris PD et al. Survival after coronary revascularization in the elderly. Circulation 2002;105:2378–84.

5. Pfisterer M. Long-term outcome in elderly patients with chronic angina managed invasively versus by optimized medical therapy: four-year follow-up of the randomized Trial of Invasive versus Medical therapy in Elderly patients (TIME). Circulation 2004;110:1213–18.

6. Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2006;113:e85–e151.

7. Pfisterer M, Buser P, Osswald S et al. Outcome of elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary artery disease with an invasive vs. optimized medical treatment strategy: one-year results of the randomized TIME trial. JAMA 2003;289:1117–23.

8. Liistro F, Angioli P, Falsini G et al. Early invasive strategy in elderly patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: comparison with younger patients regarding 30 day and long term outcome. Heart 2005;91:1284–8.

9. Bach RG, Cannon CP, Weintraub WS et al. The effect of routine, early invasive management on outcome for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:186–95.

10. De Gregorio J, Kobayashi Y, Albiero R et al. Coronary artery stenting in the elderly: short-term outcome and long-term angiographic and clinical follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:577–83.

11. Batchelor WB, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH et al. Contemporary outcome trends in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: results in 7,472 octogenarians. National Cardiovascular Network Collaboration. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:723–30.