Cardiac screening in the community is limited by time, resources and cost. We evaluated the efficacy of a novel smartphone application to provide a rapid electrocardiogram (ECG) screening method on the Island of Jersey, population 98,000.

Members of the general public were invited to attend a free heart screening event, held over three days, in the foyer of Jersey General Hospital. Participants filled out dedicated questionnaires, had their blood pressure checked and an ECG recorded using the AliveCor (CA, USA) device attached to an Apple (CA, USA) iPhone 4 or 5.

There were 989 participants aged 12–99 years evaluated: 954 were screened with the ECG application. There were 54 (5.6%) people noted to have a potential abnormality, including suspected conduction defects, increased voltages or a rhythm abnormality requiring further evaluation with a 12-lead ECG. Of these, 23 (43%) were abnormal with two confirming atrial fibrillation and two showing atrial flutter. Other abnormalities detected included atrial and ventricular ectopy, bundle branch block and ST-segment abnormalities. In addition, increased voltages meeting criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) on 12-lead ECG were detected in four patients leading to one diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

In conclusion, this novel ECG application was quick and easy to use and led to the new diagnoses of arrhythmia, bundle branch block, LVH and cardiomyopathy in 23 (2.4%) of the total patients screened. Due to its highly portable nature and ease of use, this application could be used as a rapid screening tool for cardiovascular abnormalities in the community.

Introduction

Atrial arrhythmias are often asymptomatic and can remain undiagnosed until presentation with stroke or heart failure. Pulse checks can help detect atrial fibrillation (AF) but a recorded electrocardiogram (ECG) remains the gold standard.1

Atrial arrhythmias are often asymptomatic and can remain undiagnosed until presentation with stroke or heart failure. Pulse checks can help detect atrial fibrillation (AF) but a recorded electrocardiogram (ECG) remains the gold standard.1

We set out to identify the effectiveness of a hand-held, single-lead ECG device to identify arrhythmia and other ECG abnormalities in a large, asymptomatic, unselected Island population.

Methods

The Island of Jersey has a population of approximately 98,000. Members of the general public without known heart rhythm problems were invited via advertisements in the local press and radio to attend a free heart-screening event, held over three days, in the foyer of Jersey Hospital. Participants filled out dedicated questionnaires, had their blood pressure checked and an ECG recorded using the AliveCor (CA, USA) device attached to an Apple (CA, USA) iPhone 4 or 5. Checks were performed by trained nurses and doctors. If there was suspicion of an ECG abnormality, a formal 12-lead ECG was obtained. This was then analysed by a consultant cardiologist in accordance with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria for ECG interpretation.2

Results

There were 989 participants aged 12–99 years evaluated. Two-thirds of those screened were female, the mean age was 54 years, and over half had no prior cardiovascular health problems. Comorbidities of the remainder included hypertension (27%), hypercholesterolaemia (22%), diabetes mellitus (5%), coronary heart disease, previous cardiac surgery or stroke (3%). Following their heart checks, 177 (17%) were referred to primary care for follow-up of poorly controlled hypertension, of which 60% were new diagnoses.

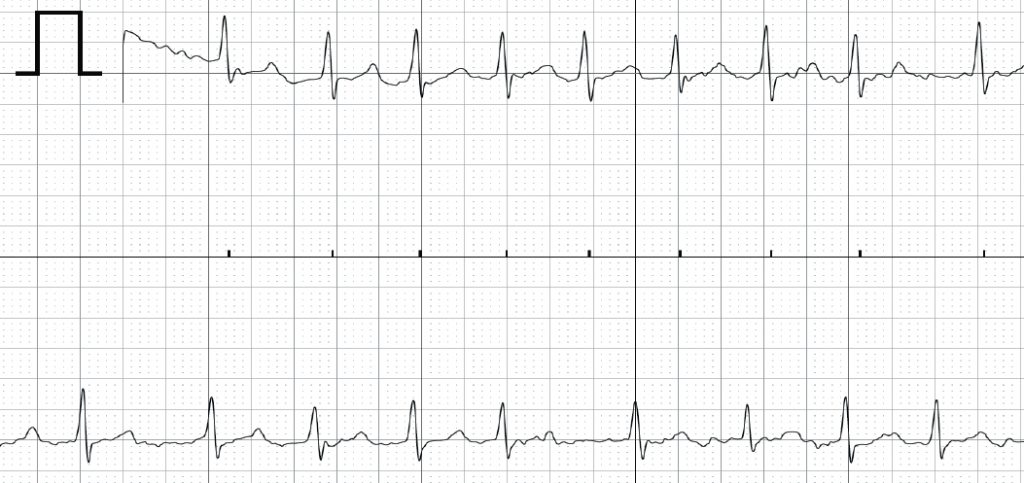

There were 954 people screened with the ECG application. ECGs were not recorded in 35 patients due to poor compliance or immediate equipment availability. There were 54 (5.6%) people noted to have a possible ECG abnormality, requiring further evaluation with a 12-lead ECG. Of these, 23 (2.4%) were abnormal (table 1) with two ECGs diagnosing AF (figure 1) and two demonstrating atrial flutter (figure 2). Other abnormalities detected included atrial and ventricular ectopy, bundle branch block and ST-segment abnormalities. Increased voltages meeting criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) on 12-lead ECG were detected in four patients leading to one diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (figure 3).

Discussion

The ECG application examined in this study was quick and easy to use and led to the new diagnoses of arrhythmia, bundle branch block, LVH and HCM in 23 (2.4%) of the total patients screened.Published data support the use of this device to screen for AF in the community,3 however, we believe that this is the first time the device has been used to look for other abnormalities.

AF is the most common clinical arrhythmia affecting 1–2% of the population, occurring more commonly with increasing age. Community screening for AF is recommended to take place in primary care with opportunistic pulse palpation.1 This method has been shown to have a sensitivity of 91% but poor specificity of approximately 74%.4 A community pharmacy study (SEARCH-AF), screening 1,000 customers across 10 pharmacies in Sydney, Australia,5 has recently reported that the ECG application used in the current study has a much higher sensitivity (98.5%) and specificity (91.4%) and is a cost-effective way to screen communities for AF.6 The study identified new AF in 1.5% of those screened with an overall prevalence of 6.7%. In our study, the AF prevalence was lower, possibly reflecting the different patient demographics with a mean age of 54 years compared with 76 years in the Australian study. The Jersey screening event was promoted as employing new digital health technology, which in its very nature may have attracted a younger audience without known disease.

One limitation of our study was that we did not record a formal 12-lead ECG on everyone, to enable us to comment on the sensitivity and specificity of ECG screening with this application. In addition, the application did not provide automatic diagnostic software at the time, so the selection of patients with abnormal ECGs was made by medical and nursing staff. The ECG recording is also limited by the single-lead ECG trace, so changes seen in cardiomyopathies, such as T-wave changes in the pre-cordial leads might not be detected. However, with future technological advances it may be possible to use similar devices to obtain simultaneous multi-lead recordings using different electrode positioning.

Conclusion

This smartphone ECG application was highly portable and easy to use, minimising the burden of resource, time and cost associated with a 12-lead ECG in community screening. In addition to identifying patients with asymptomatic atrial arrhythmias, the device was also able to help identify patients with bundle-branch block and one patient with an unknown cardiomyopathy. More widespread use of technology such as this in primary care and the community may help identify unknown cardiac conditions and reduce the complications associated with them.

Key messages

- Electrocardiograms (ECGs) can now be performed in any setting with the use of a smartphone application

- Arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter can be detected and recorded

- Other ECG abnormalities such as bundle branch block, left ventricular hypertrophy and those seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can be differentiated when trained personnel use this application

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Camm A, Lip G, de Caterina R et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. An update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm association. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2719–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253

2. Corrado D, Pelliccia A, Bjørnstad HH et al. Cardiovascular pre-participation screening of young competitive athletes for prevention of sudden death: proposal for a common European protocol. Consensus Statement of the Study Group of Sport Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005;26:516–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi108

3. Lau J, Lowres N, Neubeck L et al. Abstract 16810: Validation of an iPhone ECG application suitable for community screening for silent atrial fibrillation: a novel way to prevent stroke. Circulation 2012;126:A16810. Available from: http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/meeting_abstract/126/21_MeetingAbstracts/A16810?sid=77a8f486-738b-48e5-9d38-fbac8faf7578

4. Morgan S, Mant D. Randomised trial of two approaches to screening for atrial fibrillation in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:373–80. Available from: http://bjgp.org/content/52/478/373

5. Lowres N, Freedman SB, Redfern J et al. Screening education and recognition in community pharmacies of atrial fibrillation to prevent stroke in an ambulant population aged ≥65 years (SEARCH-AF stroke prevention study): a cross-sectional study protocol. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001355

6. Lowres N, Neubeck L, Salkeld G et al. Feasibility and cost effectiveness of stroke prevention through community screening for atrial fibrillation using iPhone ECG in pharmacies. The SEARCH-AF study. Thromb Haemost 2014;111:1167–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1160/TH14-03-0231