Data from 101 practices that had completed a survey of cholesterol target achievement using rosuvastatin in routine general practice were pooled to assess effectiveness at a national level. A total of 10,396 patients, who had total cholesterol (TC) measured prior to, and on, rosuvastatin 10 mg daily, were included in the analysis. Of these, 6,375 patients had not received a statin prior to rosuvastatin. The remainder had been switched from another statin.

Significant reductions were observed in TC (28%) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (40%) when comparing prior to and on rosuvastatin 10 mg (p<0.001). A significantly greater proportion of patients achieved the General Medical Services (GMS) Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) target of TC ≤5 mmol/L with rosuvastatin 10 mg compared with prior to rosuvastatin (81% vs. 19%; p<0.0001). Of the 580 patients who had failed to reach target on atorvastatin 10 mg daily, 70% reached target on rosuvastatin 10 mg. Similarly, 68% of 246 patients who had failed to reach target on simvastatin 40 mg daily reached target on rosuvastatin 10 mg.

General practitioners across the UK also substantially achieved other national and international cholesterol targets in patients treated with rosuvastatin 10 mg, including second line to simvastatin 40 mg and where higher doses of other statins had failed to reach target.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is responsible for over 100,000 deaths annually in the UK.1 Epidemiology studies have long supported that cholesterol is a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD).2 In both primary and secondary prevention, statin therapy trials have shown that there is a clear relationship between lowering cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular risk in both primary and secondary prevention.3 However, The World Health Report 2002 estimates that over 50% of CHD globally is still due to elevated blood cholesterol levels.4

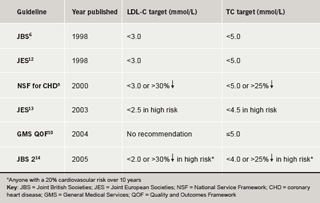

The National Service Framework (NSF) for Coronary Heart Disease set national standards for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of CHD in England in 2000.5 It suggested a total cholesterol (TC) target of less than 5.0 mmol/L for both primary and secondary prevention patients. Targets set by guideline bodies in Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales were similar.6-9 The General Medical Services (GMS) contract signed in England and Wales includes the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) which stipulated in 2004 that general practices should aim to have 60% of patients with CVD and diabetes at TC levels ≤5 mmol/L.10 This was revised in 2006, following completion of this survey, to 70% of patients at target.11 Guidance from these and other bodies in the UK and Europe is summarised in table 1 5,6,10,12-14

Despite a growing evidence base for stringent cholesterol management, studies continue to indicate that a considerable proportion of patients still fail to achieve lipid goals recommended by national and international guidelines, reflecting the need for more effective cholesterol treatment strategies.15,16

Prospective, randomised clinical trials have demonstrated that rosuvastatin is highly effective in lowering TC and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), enabling more patients to achieve cholesterol goals compared to other statins.17-19 However, randomised clinical trials do not tell us what is happening in ‘real-life’ routine general practice. Furthermore, prospective trials can influence and bias clinical practice. This retrospective series of audits of cholesterol management in UK primary care centres enabled an assessment of the performance of low-dose rosuvastatin in achieving present and evolving targets in ‘real-life’ routine clinical practice.

Methods

An audit service, provided by AstraZeneca, was offered to primary care practices as a service to medicine (no incentives were offered for this service). It provided a retrospective assessment of achievement of national cholesterol targets with rosuvastatin in routine clinical practice to general practices in the UK. At the request of individual primary care practices, electronic practice records were searched to identify patients who had been prescribed rosuvastatin. The following anonymised data were collected for each of these patients: statin treatment prior to rosuvastatin (none, or statin and dose), last cholesterol test prior to rosuvastatin (TC and, where available, LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] and triglycerides [TG]), first rosuvastatin treatment (date and dose), first cholesterol test after starting rosuvastatin (TC and, where available, LDL-C, HDL-C and TG). Following data collection, collation and statistical analysis, individual practices were provided with an audit report for their own practice.

This UK nationwide survey brought together data from the local audits to assess the effectiveness of the start dose of rosuvastatin. The data presented here were collected during an 18-month period covering 2004/2005. The faculty wrote to all 150 practices that had completed audits by the end of December 2005 requesting permission to include the anonymised data from their practice in a national report. Permission to include information was granted by 101 of the practices that were approached, with the majority of the remaining practices being non-responders.

Anonymised data from each practice was pooled into a single database for analysis. Patients were included in the analysis if they had been initiated on a start dose of rosuvastatin (10 mg or 5 mg) and had a TC result recorded prior to and on rosuvastatin. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they did not have a prior result relating to their treatment at the time of rosuvastatin initiation. All other results were included. Full lipid profiles were not available for all patients as not all laboratories would regularly provide GPs with this information. Where LDL-C was not recorded but TC, HDL-C and TG were available, LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald equation unless TG exceeded 4.5 mmol/L.20 Patients were included in analyses of LDL-C, HDL-C and TG if they had results for that measure prior to and on rosuvastatin 10 mg.

The demographic and prior treatment data are presented descriptively. Statistical comparisons of the proportion of patients achieving guideline TC and LDL-C targets were conducted using McNemar Change Test. Patients were assessed against the GMS target,10 Joint British Societies (JBS) 1998 guidelines,6 Joint European Societies (JES) 2003 guidelines13 and JBS 2 2005 guidelines14 (table 1). Statistical comparisons between TC test results prior to and on rosuvastatin were conducted using Student’s paired t-test. LDL-C, HDL-C and TG were also compared using the Student’s t-test for those patients who had the relevant test prior to and on rosuvastatin. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether the results were robust to the inclusion of patients who had a delay between the initiation of rosuvastatin and TC testing of greater than six months, and the exclusion of patients with no results prior to rosuvastatin.

Results

Patient characteristics

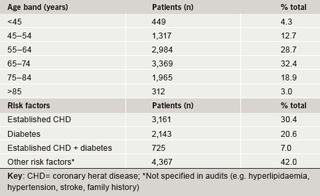

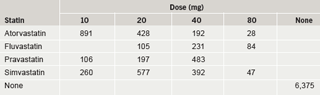

A total of 14,747 patients from 101 practices had a prescription for rosuvastatin 10 mg. No patients in this audit had been initiated on 5 mg. TC test results were available prior to and on rosuvastatin for 10,396 patients. Patient characteristics are summarised in table 2. Notably, over 54% of the survey population were elderly (age ≥65 years). Altogether 6,375 patients had not received a statin prior to rosuvastatin and for the purposes of this study are classified as ‘new’ patients. The remaining patients (n=4,021) had switched from another statin (‘switch’ patients). The prior statin and dosage recorded are summarised in table 3. The statins most commonly prescribed were simvastatin (32% of switch patients, most common doses 20/40 mg) and atorvastatin (38% of switch patients, most common dose 10/20 mg).

Lipids

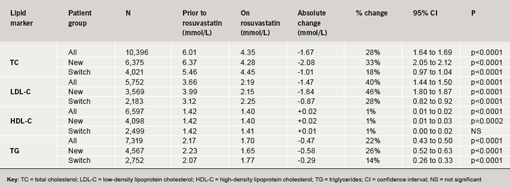

The baseline TC level in the ‘all patients group’ was 6.01 mmol/L (n=10,396). There was a statistically and clinically significant TC reduction of 28% (p<0.0001) when comparing prior to and on rosuvastatin (10 mg) use. This reduction was seen in both the new (33%) and switch (18%) patient groups (p<0.0001 for both groups; table 4). Full lipid profiles were not available for all patients. Hence, only 5,752 patients had LDL-C values recorded. Baseline LDL-C in the ‘all patients group’ was 3.66 mmol/L. Rosuvastatin (10 mg) induced a clinically significant reduction in LDL-C of 40% (46% in new and 28% in switch patients; p<0.0001 for all three groups). HDL-C data were available for 6,597 patients. The changes seen for HDL-C, were under the limits of sensitivity of the analytical tests21 although reaching statistical significance in the ‘all patients’ and ‘new’ group (table 4). TG measurements were available for 7,319 patients. TG levels were 2.17 mmol/L prior to rosuvastatin, and were reduced by 22% on rosuvastatin 10 mg (n=7,319; p<0.0001).

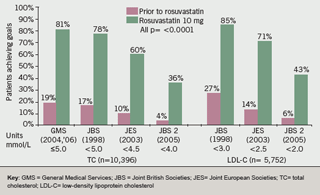

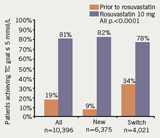

GMS QOF cholesterol target

The proportion of patients achieving the target of TC ≤5 mmol/L was clinically and statistically significantly greater after rosuvastatin 10 mg was prescribed compared to before for the ‘all patient’ group (81% vs. 19%), the ‘new patient’ group (82% vs. 9%) and the ‘switch patient’ group (78% vs. 34%) (all p<0.0001) (figure 1). This cholesterol lowering surpassed both the GMS 2004 and 2006 QOF targets (figure 2).

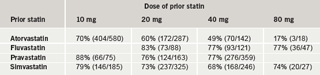

In patients previously treated with atorvastatin, 70% of patients who failed to attain a TC level of ≤5 mmol/L on atorvastatin 10 mg, and 60% of patients who failed to reach target on atorvastatin 20 mg, reached target on rosuvastatin 10 mg. Patients reached the QOF target (TC ≤5 mmol/L) on rosuvastatin 10 mg who had previously failed to reach target on higher doses of atorvastatin, such as 40 mg and 80 mg (table 5). In addition, 68% of patients who failed to reach target on simvastatin 40 mg reached target on rosuvastatin 10 mg, and the majority of those patients who failed to reach target on all other simvastatin doses reached target on rosuvastatin 10 mg (table 5).

Evolving cholesterol targets

The impact of evolving, increasingly stringent cholesterol targets on all patients reaching targets is shown in figure 2. These show that significantly more patients in all patient groups (i.e. all, switch and new) who were prescribed rosuvastatin 10 mg reached JBS (1998) targets of TC ≤5 mmol/L and LDL-C of <3 mmol/L, the JES (2003) targets of TC <4.5 mmol/L and LDL-C <2.5 mmol/L, and the JBS 2 (2005) targets of TC <4 mmol/L and LDL-C <2 mmol/L, when compared to prior to rosuvastatin.

Sensitivity analysis

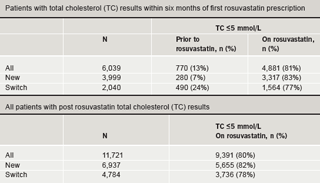

Sensitivity analyses were performed on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion of patients who did not have TC recorded within six months of their first rosuvastatin prescription made little difference to proportions reaching the QOF TC ≤5 mmol/L target and the difference between achievement of targets on rosuvastatin and prior to rosuvastatin remained statistically significant (p<0.0001) (table 6).

Inclusion of patients who did not have a cholesterol measurement prior to rosuvastatin also showed little difference to the achievement of targets on rosuvastatin treatment (table 6).

Discussion

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) are the ‘gold-standard’ for assessing the efficacy and safety of clinical interventions but they do not always reflect a ‘normal, real-world’ population. In this study, patients were those, who in the opinion of their doctor, would benefit from being prescribed rosuvastatin, including those often excluded from RCTs e.g. the elderly and those with other medical conditions. They were treated according to normal clinical practice with no special study visits, medication or investigations. Moreover, as the provision of the audit service and the collection of data was retrospective, it occurred after the GPs’ clinical decisions had been made. One factor that may have influenced a change in GP behaviour over the period when treatment decisions were made was the introduction of the QOF target of 60% (since increased to 70%) of CVD patients, including those with diabetes, reaching a TC ≤5.0 mmol/L.10,11 This would have affected all practices, however, not just those participating in the audit, and thus reflects routine clinical practice.

In international clinical studies, rosuvastatin has been shown to be effective in lowering TC and LDL-C, and enabling more patients to achieve cholesterol goals compared with other statins.17-19 Extensive safety data indicate that rosuvastatin has a similar safety profile to other statins.22-28 A UK randomised study, DISCOVERY, designed to be similar to routine clinical practice, assessed the effectiveness of rosuvastatin 10 mg compared with other statins in statin-naïve patients.18In that study, 81% of patients (compared to 82% of patients in this survey), achieved a TC target of <5 mmol/L on rosuvastatin 10 mg, compared with 59% of patients on atorvastatin 10 mg and 51% of patients on simvastatin 20 mg.18 The percentage reductions in TC and LDL-C seen in DISCOVERY (34% and 50%, respectively) and this survey (33% and 46%, respectively) with rosuvastatin 10 mg were similar. Overall, the results achieved with rosuvastatin 10 mg in this ‘real-life’ survey appear comparable with previously observed results achieved in RCTs.

Implications for practice

QOF targets highlight the national importance attached to improving health outcomes in this disease area. QOF points are awarded based on the percentage of patients on a practice’s CHD register who have a record of TC in the last 15 months and who have reached a TC ≤5 mmol/L. Maximum points are awarded to GP practices if at least 60% (QOF 2004) or 70% (QOF 2006) of CHD and diabetes patients, and 60% of stroke patients (QOF 2004 and 2006) have a TC ≤5 mmol/L.10,11

There is increasing financial pressure in the NHS to reserve branded statins for patients who are not controlled on generic statins, primarily simvastatin. These results indicate that the second-line use of rosuvastatin 10 mg in patients not achieving targets on simvastatin 40 mg will increase the proportion of patients achieving QOF targets.

The evolving evidence that greater reductions in LDL-C are associated with greater reductions in cardiovascular events led to both JES13 and JBS15 reducing their treatment targets. The majority of patients were are able to achieve the lower JES targets of TC <4.5 mmol/L (60%) and LDL-C <2.5 mmol/L (71%) on rosuvastatin 10 mg. A significant proportion of patients were also able to achieve the more stringent JBS 2 targets of TC <4.0 mmol/L (36%) and LDL-C <2.0 mmol/L (43%) on a low dose of rosuvastatin 10 mg. Some of the patients unable to reach the most stringent targets on the start dose of rosuvastatin may require titrating to a higher dose.

There are potential areas of bias that may have influenced the study. Patients were treated with rosuvastatin according to clinical need and clinicians may have reserved its use for patients with a higher clinical need. It is possible that those practices that undertook audits and those that chose to participate in the national analysis may not be typical of practices in the UK. Although these audits took place at a time when QOF made an audit appropriate, the GPs who conducted audits may have had a greater interest in cholesterol management than those who did not, or may have had additional support available for patients that increased their understanding of their disease and subsequent compliance. Results from another study conducted using a national database with no selection bias towards interest in specifically cardiovascular medicine, however, obtained similar results in a smaller group of patients, indicating that any differences in clinical support in the survey practices did not influence results substantively.29 In addition, the sensitivity analyses confirm that neither the inclusion of patients who were tested more than six months after commencing therapy, nor the exclusion of patients who had no pre-treatment cholesterol test recorded significantly affect the results.

The 2006 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on the use of statins will, it is estimated, result in an additional 3.3 million patients in England and Wales being eligible for statin use.30 The Hyperlipidaemia Guidelines expected from NICE in early 2008 may further modify the number of patients eligible. NICE guidance clearly recommends that the choice of statin at initiation should usually be based on a low acquisition cost, taking into account required daily dose and product price per dose.30 Based on this guidance a generic statin should be the first-line choice. A review has shown that rosuvastatin is the next most cost-effective statin option31 and it is shown here to be clinically effective at reaching cholesterol targets as a second-line option.

In conclusion, this survey confirms the effectiveness of rosuvastatin 10 mg daily in ‘real life’ everyday clinical practice. GPs across the UK are achieving the target of ≤5 mmol/L in the majority of patients treated with rosuvastatin 10 mg, including second line to simvastatin 40 mg and where higher doses of other statins have failed to reach this target. Many patients are also achieving the lower European and JBS 2 targets on rosuvastatin 10 mg, although clinicians may need to consider titration in those patients if trying to achieve these more stringent targets.

Acknowledgement

W thank the 101 practices who contributed their data to this national study.

Conflict of interest

AstraZeneca UK Ltd. provided financial support for the medical writing of this article and provided the services of Dr Diane Wass (AstraZeneca) for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

GK has received honoraria for speaking at symposia and attended advisory boards and chaired meetings for a number of pharmaceutical companies including AstraZeneca. JR has attended meetings, provided consultancy, received honoraria from AstraZeneca (before 2006), and from other pharmaceutical companies related to statins and other lipid treatments. CE is an employee of AstraZeneca. ME has attended advisory boards and chaired meetings for a number of pharmaceutical companies including AstraZeneca. AT has received honoraria for speaking at meetings sponsored by AstraZeneca. AV has received honoraria for speaking at meetings sponsored by AstraZeneca.

Key messages

- The majority of patients reach the target of total cholesterol (TC) ≤5 mmol/L with rosuvastatin 10 mg compared with prior to rosuvastatin (81% vs. 19%)

- In order to drive cost-effective strategies, generic statins should usually be used first line reserving branded statins for second-line use if sufficient cholesterol lowering is not achieved

- In patients who failed to reach the target of TC ≤5 mmol/L on simvastatin 40 mg, seven out of 10 patients reached target on rosuvastatin 10 mg, with higher proportions reaching target on rosuvastatin who had failed on all other generic statin doses

- Rosuvastatin helped greater proportions of patients reach the more stringent Joint European Societies and Joint British Societies (JBS 2) targets

References

- Allender S, Peto V, Scarborough P et al. Coronary heart disease statistics. British Heart Foundation: London, 2006.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 2004;364:937–52.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–78.

- World Health Organization. The world health report 2002. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2002.

- Department of Health. National service framework for coronary heart disease. Modern standards and service models. London: Department of Health, March 2000. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Policyandguidance/Healthandsocialcaretopics/Coronaryheartdisease/index.htm [accessed 3/5/2007].

- Joint British Societies. Recommendations on prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Heart 1998;80(suppl 2):S1–S29.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Guideline 97. Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Edinburgh: SIGN, February 2007. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign97.pdf [accessed 3/5/2007].

- All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. Use of statins in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cardiff: All Wales Medicines Strategy Group, March 2005. Available from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk [accessed 3/5/2007].

- The Department of Health and Children. Building healthier hearts: the report of the cardiovascular health strategy group. Dublin: Department of Health and Children, 1999. Available from: http://www.dohc.ie/publications.

- Department of Health. GMS Quality and Outcomes Framework. London: Department of Health, August 2004. Available from: http://www.doh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/86/93/04088693.pdf [accessed 1/3/2007].

- Department of Health. Investing in general practice. The new general medical services contract. London: Department of Health, 2006. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/13/72/68/04137268.pdf [accessed 3/5/2007].

- Wood D, De Backer G, Faergeman O et al. Task Force Report. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the second joint task force of European and other societies on coronary prevention. Eur Heart J 1998;19:1434–1503.

- De Backer G, Ambrosiani E, Borch-Johnsen K et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third joint taskforce of European and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2003;17:1601–10.

- Joint British Societies’. Guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice (JBS 2). Heart 2005;91(suppl):v1–v52.

- Patel J, Kirby M, Hughes EA. The lipid audit: analysis of lipid management in two centres in Britain 2003. Br J Cardiol 2004;11:214–17.

- Evans PH, Luthra M, Pike C et al. NSF lipid targets in patients with CHD. Are they achievable in a real-life primary care setting. Br J Cardiol 2004;11:71–4.

- Schuster H, Barter PJ, Stender S et al.; Effective reductions in cholesterol using rosuvastatin therapy I study group. Effects of switching statins on achievement of lipid goals: Measuring Effective Reductions in Cholesterol Using Rosuvastatin TherapY (MERCURY I) study. Am Heart J 2004;147:705–13.

- Middleton A, Fuat A. Achieving lipid goals in real life: the DISCOVERY-UK study. Br J Cardiol 2006;13:72–6.

- Hobbs FD, Southworth H. Achievement of English National Service Framework lipid-lowering goals: pooled data from recent comparative treatment trials of statins at starting doses. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:1171–7.

- Friedewald WT, Levy RJ, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without the use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499–502.

- Fallest-Strobl PC, Olafsdottir E, Wiebe DA et al. Comparison of NCEP performance specifications for triglycerides, HDL-, and LDL-cholesterol with operating specifications based on NCEP clinical and analytical goals. Clin Chem1997;43:2164–8.

- AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca rosuvastatin clinical information website. Available from: www.rosuvastatininformation.com [accessed 11/7/2007].

- Shepherd J, Vidt DG, Miller E et al. Safety of rosuvastatin: update on 16,876 rosuvastatin-treated patients in a multinational clinical trial program. Cardiology 2007;107:433–43.

- National Lipid Association. Supplement on statin safety. Am J Cardiol 2006;97(8 suppl 1):1–98.

- McAfee A, Ming E, Seeger J et al. The comparative safety of rosuvastatin: a retrospective matched cohort study in over 48,000 initiators of statin therapy. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety 2006;15:444–53.

- Goettsch W, Heintjes E, Kastelein J et al. Results from a rosuvastatin historical cohort study in more than 45,000 Dutch statin users, a PHARMO study. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety 2006;15:435–43.

- Johansson S, Ming E, Wallander M et al. Rosuvastatin safety: a comprehensive, international pharmacoepidemiology programme. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety 2006;15:454–61.

- Kasliwal R, Wilton L, Shakir S. Safety profile of rosuvastatin: results of a prescription-event monitoring study in 11680 patients. Drug Safety 2007;30:157–70.

- Heintjes E, Hirsch MW, O’Donnell JC et al. Differences in percentage low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction and goal attainment among newly initiated users of statins in a real life setting. Value in Health2006;9:A197.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular events. NICE technology appraisal 94. London: NICE, 2006. Available from: www.nice.org.uk [accessed 3/5/2007].

- Davies A, Hutton J, O’Donnell J, Kingslake S. Cost-effectiveness of rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, pravastatin and fluvastatin for primary prevention CHD in the UK. Br J Cardiol 2006;13:196–202.