Chronic heart failure (CHF) is one of the major health challenges in the 21st century. As might be expected from a chronic condition, which increases in prevalence with age, CHF is often accompanied by one or more co-morbid conditions. Many of these add to the patient’s symptom burden and to the complexity of managing the CHF. In addition, a few common co-morbid conditions are related intimately to the CHF disease process itself and may be, at least in part, the consequence of the heart failure syndrome. They may also contribute to its progression. Renal impairment and anaemia are the best-recognised conditions in this context and are frequently found together in the presence of CHF. There are multiple mechanisms by which anaemia may arise in the CHF population. Iron deficiency anaemia is relatively common in CHF and, given the potential for its correction, this type of anaemia has been the focus of a great deal of clinical and research interest. The aim of this article is to consider the prevalence of anaemia – iron deficiency or otherwise – in CHF, and its impact on morbidity and mortality.

Prevalence

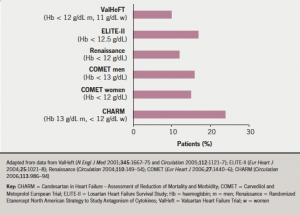

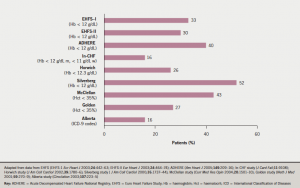

In published reports of patients with heart failure, the prevalence of anaemia varies markedly, reflecting the very varied characteristics of the studied populations. In reports based upon clinical trials, the reported prevalence ranges from 10–25% (figure 1), while in cohorts of patients in observational or registry-based studies, it appears to be higher, from 15–50% (figure 2). This variation is unsurprising given the relatively selected nature of patients recruited to clinical trials in CHF. A reasonable overall estimate can be gleaned from a large systematic review of 34 studies, including more than 150,000 patients, in which anaemia prevalence was approximately 37%.1 Anaemia is more often seen in women with CHF. It is very uncommon in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular impairment, but becomes increasingly common as symptoms become more severe – 20% of patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II CHF are anaemic, rising to more than 50% of patients with NYHA class III and IV CHF.

It is interesting to note that the prevalence of anaemia increases with time in cohorts of patients with CHF: in other words, there is an incidence of new-onset anaemia. In SOLVD (Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction),2 approximately 9% of patients developed anaemia within the first year of follow-up. In COMET (the Carvedilol and Metoprolol European Trial),3 anaemia increased in prevalence from 14% at one year of follow-up to over 25% at five years. Importantly, the development of anaemia is an important indicator of adverse outcome, which will be discussed below.

Impact on quality of life

As already discussed, anaemia is a common co-morbidity in CHF and shows a clear adverse association with quality of life. Haemoglobin shows graded, inverse association with objective measures of exercise capacity, such as maximum oxygen uptake. Data from the CHARM (Candesartan in Heart Failure – Assessment of Reduction of Mortality and Morbidity) studies show that both cardiovascular and

non-cardiovascular hospital admissions are more common in patients with CHF and anaemia.4 The change in haemoglobin over time is also related to change in quality of life. For example, quality of life falls in those patients in whom haemoglobin falls, and improves in proportion to the increase in haemoglobin in those patients in whom this occurs.

Impact on life expectancy

In addition to impacting on quality of life, lower haemoglobin shows a strong, graded association with the risk of death for patients with CHF. In the systematic review and meta-analysis referred to above,1 anaemia was associated with an approximate doubling of the risk of death and was an independent marker of the likelihood of death over six months’ follow-up. In the CHARM studies,4 anaemia was associated with increased risk of death both in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and in those with preserved left ventricular function.

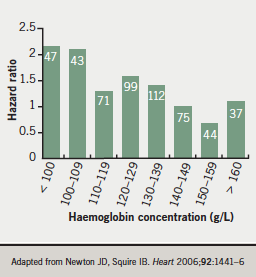

In a cohort of 528 consecutive patients admitted to hospital for the first time with the diagnosis of heart failure,5 anaemia was seen in 39% of men and 43% of women. Any reduction in haemoglobin below the normal reference range was associated with approximately 40% increase in mortality risk, with a very clear, graded relationship with the risk of death during follow-up (figure 3).

Conclusion

Anaemia is common in patients with CHF and is associated with adverse impact on quality of life and survival.

Key messages

- Anaemia in CHF is common

- It negatively impacts on quality of life and survival

References

- Groenveld HF, Januzzi JL, Damman K et al. Anemia and mortality in heart failure patients a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:818–27.

- Al-Ahmad A, Rand WM, Manjunath G et al. Reduced kidney function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:955–62.

- Komajda M, Anker SD, Charlesworth A et al. The impact of new onset anaemia on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from COMET. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1440–6.

- O’Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB et al. Clinical correlates and consequences of anemia in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: Candesartan Assessment of Reduction of Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) programme. Circulation 2006;113:986−94.

- Newton JD, Squire IB. Glucose and haemoglobin in the assessment of prognosis after first hospitalisation for heart failure. Heart 2006;92:1442–6.

Round table discussion

How do we define

anaemia?

The panel considered it important to agree a definition of anaemia. Many investigators use the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, initially proposed in 1968, in which the threshold for anaemia in men over 15 years is a haemoglobin concentration <13.0 g/dL; and for non-pregnant women <12.0 g/dL. Debate continues as to whether these values are appropriate in the elderly, whether there should be sex differences, and whether they are appropriate in CHF.

The group agreed that the level decided upon should ideally be evidence-based and should be the level “which impacts on prognosis”. Data from the ELITE II study1 showed a haemoglobin level of around 14.5 g/dL was associated with best prognosis, whereas below this level, there was “quite a marked step down in the likelihood of survival”. Other findings from the literature suggest there may be a level (around 12.5 g/dL) at which we might “dichotomise the association with adverse outcomes” (in other words, there is a major association with increased mortality below this value).

Caution is required when discussing anaemia, iron deficiency anaemia and iron deficiency with normal haemoglobin levels as they are not the same entity. Patients may exhibit iron deficiency yet have ‘normal’ haemoglobin values. Indeed iron deficiency per se is an independent predictor of mortality in CHF. Furthermore, we do not have ideal markers of iron deficiency, and those commonly used, such as ferritin, may have a very wide ‘normal’ range e.g. 12–200 µg/L. A low ferritin level within the normal range may not be biologically ideal. Although it is key to have a definition to ‘prompt’ physicians, patients with CHF are different from healthy subjects and even patients with gastrointestinal disease. In summary, the optimal haemoglobin level in CHF is not known. Patients with a haemoglobin level below WHO or local laboratory quoted normal ranges, such as 12 or 13 g/dL (with some debate on whether there is a sex-specific difference) should be the focus for further investigation and consideration for treatment. Some patients with haemoglobin in the normal range who remain symptomatic may also have iron deficiency which might warrant attention.

Reference

- Sharma R, Francis DP, Pitt B et al. Haemoglobin predicts survival in patients with chronic heart failure: a substudy of the ELITE II trial. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1021–8.